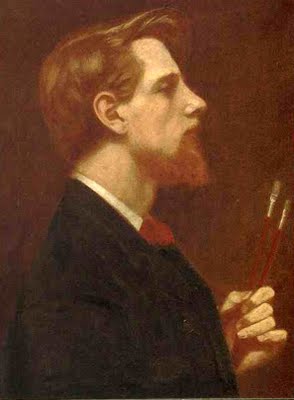

Self Portrait with Two Square Brushes by Thomas Gotch

My featured artist today is the British painter, Thomas Cooper Gotch. Little has been written about Thomas Gotch and in a way, he appears to be the forgotten man. Part of the reason for this is that he was an unassuming man who preferred to take a step back rather than be in the limelight. Another possible reason was that he never associated himself with painting “schools” and it is hard to compartmentalise his painting style. In the pre-1890’s, his works were mainly depictions of open spaces, subdued in colour and yet full of detail, but then later came his more symbolist-style works. Gotch was unhappy in the way some of his contemporaries painted only what would sell, or as he put it, they painted down to the level of the market, and further derided them by saying that they grew rich as tradesmen but following that path, they lost as artists. Having said that, Gotch was aware that he had to survive financially and took on painting commissions, especially portraiture ones. Once he had earned the money from a portraiture commission, he was happy to return to his Newlyn home, Wheal Betsy, overlooking Mount’s Bay and relax by working on one of his charming landscapes featuring local views of his beloved Cornwall.

Thomas Cooper Gotch, with the fair hair, sits on his maternal grandmother’s knee whilst his older brother John Alfred Gotch stands by the side of his mother. The father stands at the back of the family group.

To fully understand the person, we need to look at his family and his early life. Thomas Cooper Gotch was born on December 10th, 1854 in the Mission House, Kettering, in rural Northamptonshire, a landlocked county located in the southern part of the East Midlands region. His parents were John Henry Gotch and Mary Anne Gale Gotch. He was the fourth surviving son of the couple. His father, John Henry, and his father’s two brothers, John Davis Gotch and Frederick William Gotch had inherited the family wealth when their father passed in 1852. The three men had been bequeathed two businesses, a family shoe and boot establishment which was subsequently managed by John Davis Gotch and the J.C. Gotch and Sons bank, managed by his father, John Henry Gotch. The artist’s father, John Henry was well suited to run a bank as he was an exceptionally talented mathematician. His younger brother Frederick William played no part in the family businesses and instead became a renowned Hebrew scholar and later was elected President of the Baptist Union.

A Cottage in a Garden by Thomas Gotch

All was going well for the family businesses until 1857 when a combination of events led to a financial disaster for the family. Firstly, 1857 was the year of a financial panic in the United States which resulted in the declining international economy and over-expansion of the domestic economy. Due to the advance of telecommunications at the time, it meant that the world economy was also more interconnected, which also made the Panic of 1857 the first worldwide economic crisis. Secondly, and more connected with the Gotch bank, John Henry Gotch had been authorising a number of unsecured financial loans, a number of which were given to the Rev. Allan Macpherson, the curate of Rothwell, without due diligence and with the downturn of 1857 the bank collapsed as did the shoemaking business under the terms of unlimited liability. The bankruptcy meant that the brothers had to sell their Mission House and auction off most of the furnishings as well as selling the adjoining shoe factory to pay off creditors. John Henry Gotch sadly realised that authorising so many loans without investigating the circumstances of the borrowers was his fault.

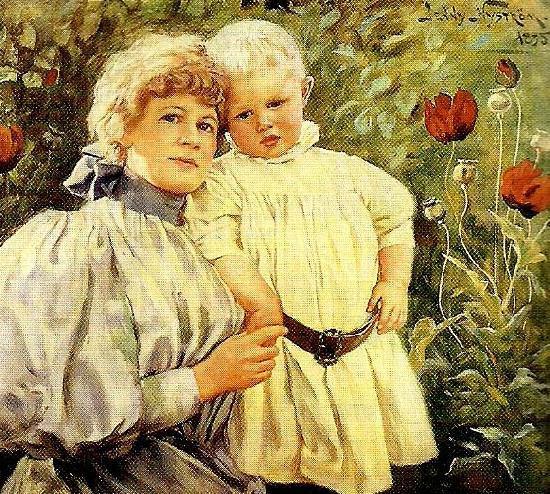

Ruby by Thomas Gotch

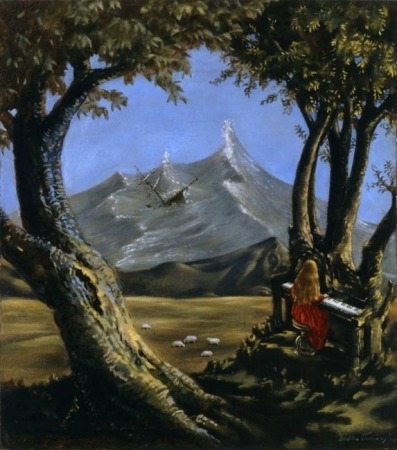

Perhaps poking fun at the prevalence of red-headed women in Pre-Raphaelite art, an acquaintance bet Gotch that he could not paint a red-haired subject with red cheeks in red clothes. This painting of Ruby Bone, a local girl who would have been little over two years old when she sat for the portrait, was the artist’s response. The warm oranges and reds of the sitter’s hair and clothes are balanced against the dull green-grey of the background and off-white of her dress and buttons.

After the financial collapse of the two businesses, John Henry Gotch, along with his wife and family were now homeless and had to rely on the kindness of relatives, including his wife’s brother’s family, the Hepburns, for somewhere to stay. In 1858 they managed to rent a house in Ilford, Essex and this is where his wife gave birth to a daughter, Jessie. It took John Davis Gotch until 1863 to have the bankruptcy discharged thanks in the main to money that he borrowed from the Hepburns. He then set about to revive the family shoemaking business and invited John Henry to join him.

The Lady in Gold. A Portrait of Mrs John Crooke by Thomas Gotch

The present picture dates from the turning-point in Gotch’s career since it was painted in Newlyn early in 1891 and exhibited at the Royal Academy that summer, shortly before he made the visit to Florence which had such a dramatic effect on his style. The sitter’s husband had already commissioned Gotch to paint a small watercolour portrait of her, which was exhibited at the New Gallery in 1890.

Thomas Cooper Gotch attended the Church of England boarding school, Foy’s Academy in West Brompton and, along with his brother Alfred, was looked after during long weekends and school holidays by Thomas and Mary Ann Hepburn. By 1863 the family’s financial problems had eased and Thomas Gotch along with his parents and four siblings returned to live together in Kettering. Thomas Gotch remained at the Foy’s boarding school until 1869, aged nine. He returned to live with his family in Kettering and attended the Kettering Grammar School where he was given an “A” for effort but struggled. He left school in 1872 and in March 1873 he began working at his father’s boot and shoe business.

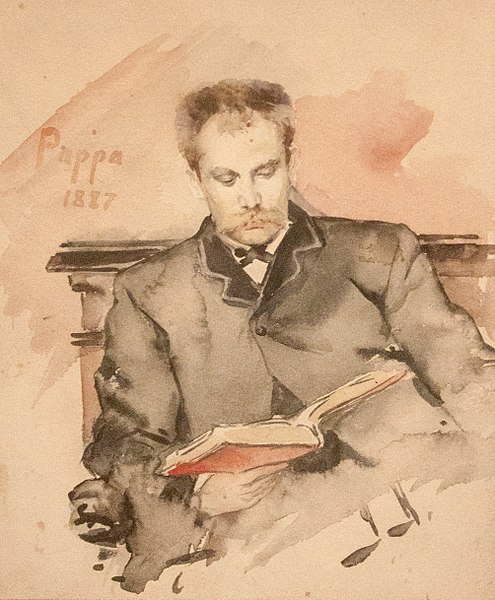

The Orchard by Thomas Gotch (1887)

Working in the shoe and boot industry was not what Tom wanted but on the other hand he did not know what he wanted! He had a hankering for writing and submitted a few of his stories to a publisher to be edited but there is no record of what was thought of his literary efforts but what we do know is that he continued writing stories throughout his life. So, what made Thomas Cooper Gotch take up painting? He never recorded his decision to take up painting in any of his diaries or writings so there is a mystery about what first led him towards an artistic career. It is known that his mother, Mary Anne, enjoyed sketching and her sister, Sarah Gale had married John Frederick Herring Snr., an animal painter, sign maker and coachman in Victorian England. It was also at the insistence of his mother that Thomas always took his painting paraphernalia with him when he went off on holiday. Whatever happened, Thomas Gotch decided to follow the artistic path of life and in May 1876, aged 21, he applied to attend Heatherley’s Art School, one of the oldest independent art schools in London, submitting the required specimens of his work. Attending Heatherley’s was a steppingstone to entering other art schools. Whilst at Heatherley’s Thomas Gotch had his work critiqued by well-known practicing artists.

Rosalind by Thomas Gotch

Buoyed by the praise he received from the lecturers at Heatherley’s, Thomas Gotch applied to the Academy Schools and was taken aback when he was refused entry. A second application was also rejected and Thomas began to believe the training he had been receiving at Heatherley’s was at fault and so, in October 1877, accompanied by his friend Edward Laurie, he travelled to Antwerp where they enrolled at the Ecole des Beaux Arts, where the Professor of Art was the Belgian painter and watercolourist, Charles Verlat. It was not a happy time for Gotch who railed against the school’s endorsement of traditional subject matter and the use of a dark palette whilst he preferred brighter colours and a more decorative approach. He commented on this to his long-standing friend and previous fellow Heatherley’s student, Jane Ross. In his letter to her, he wrote:

“…Here we must do what we are told with as good as grace as we can and if we break the rules are reminded that we are only allowed in the school as a favour. Each week, there is a fresh figure wheeled into the room and all who are drawing figures have obediently to draw that and nothing else…”

Clouds by Thomas Gotch

At the end of February 1878, Thomas Gotch, having completed his painting and drawing examinations, decided to leave Antwerp. He was disheartened by the experience and would have returned home but his brother Alfred joined him in the city and although he could not persuade his brother to stay at the Ecole des Beaux Arts, he did persuade him to carry on with his art and return to London and resume his artistic studies at Heatherleys. Thomas returned to Heatherleys at the end of March 1878 and also enrolled as a private student with the English portrait painter, Samuel Lawrence. Following a number of arguments with the family he realised that to be financially independent he would have to become a successful artist. During the summer of 1878 he set himself the task of completing a number of landscape paintings. He and his artist student friend, John Smith, rented a small house in the village of Goring-on-Thames and set about painting scenes of the surrounding countryside and various farmyard scenes. Thomas Gotch was accepted into the Slade School of Fine Art in October 1878 where he remained for two years. His love of literature encouraged him and some of his fellow art students to form a Shakespeare Reading Society at which they would read the plays.

……………………………………………..to be continued.

.jpg?mode=max)

.jpg)