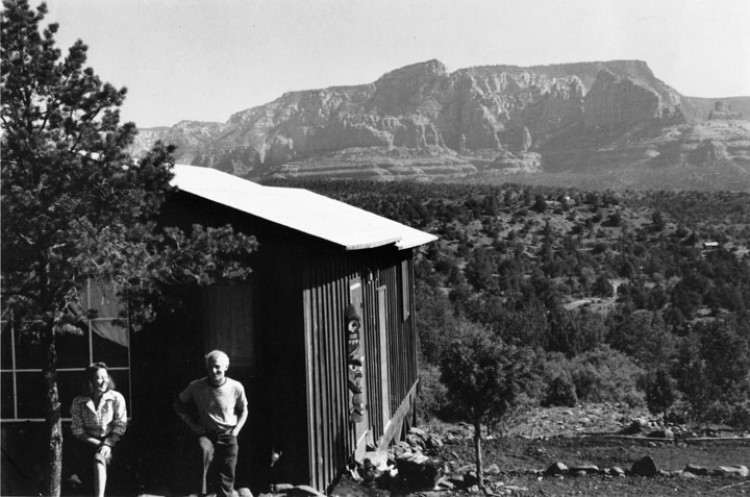

Dorothea and Max Ernst divided their time between their Arizona home in Sedona and their apartment in New York. Often Tanning would return to New York to show her work at the Julien Levy Gallery in Midtown Manhattan. In April 1944, the Julien Levy Gallery held Dorothea’s first one-person exhibition.

That same year, 1944, Dorothea completed her painting entitled Fête Champêtre depicting a popular form of entertainment in Baroque France during the 18th century, taking the form of a garden party. In Tanning’s work an unusual desert landscape provides the setting and she has added a marble mantelpiece and an ornate rococo clock. She has also populated the depiction with a number of unidentifiable figures, some of which are human others are anthropomorphic, adding human characteristics to nonhuman things. However, we can clearly see a bearded man and a girl who sits beside him, both staring out at something invisible to us. The whole depiction remains a mystery as to what it is all about.

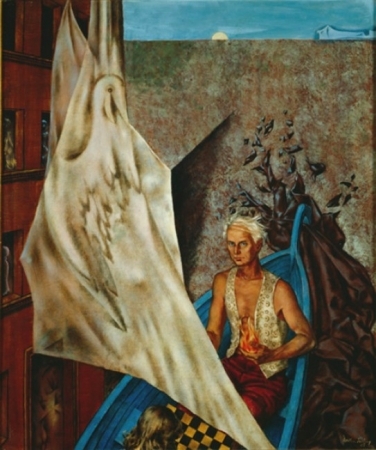

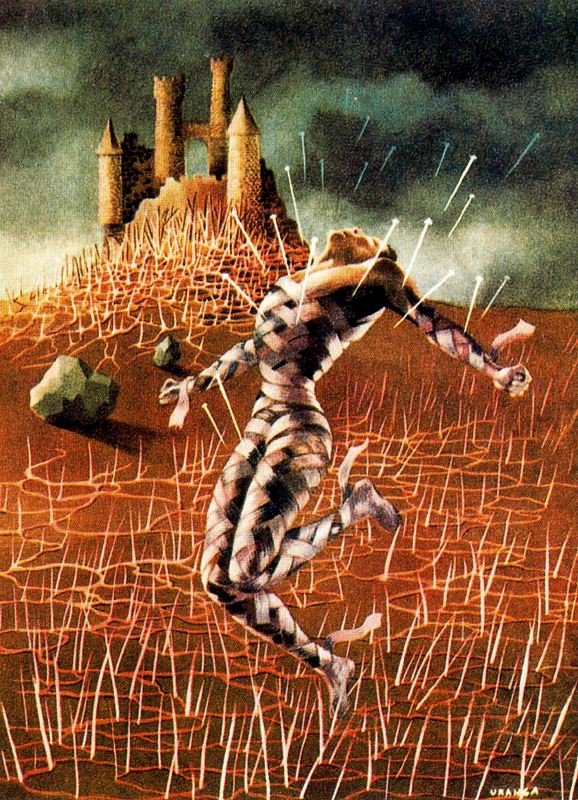

Whilst in New York,in 1945, Dorothea Tanning, completed a work which focused on a biblical scene that has been depicted by many famous artists, such as Dali and Hieronymus Bosch. The painting is entitled The Temptation of St Anthony, which is now the property of Philadelphia’s La Salle University Art Museum. The painting portrays the supernatural temptation reportedly faced by Saint Anthony the Great during his stay in the Egyptian desert. Saint Anthony, then aged 35, decided to spend the night alone in an abandoned tomb. A great multitude of demons came and started beating him, wounding him all over. He lay on the ground as if dead and the claws of the demons prevented him from getting up. According to the hermit the suffering caused by this demonic torture was comparable to no other. Terrified and brought to his knees in fear, the habit that he is wearing wafts upwards as if caught in a gale-force updraft. The blue, green and pink folds of the habit expose images of feminine shapes that seem to be the cause of his anguish.

Dorothea created the work for the Bel Ami International Art Competition, where twelve surrealist and magic realist painters were asked to submit a painting to be used in Albert Lewin’s film The Private Affairs of Bel Ami, based on Guy de Maupassant’s novel Bel Ami. The rules of the competition for a cash prize were that the painting should be 36 × 48 inches and on the subject of the temptation of Saint Anthony. It would be shown as the only colour segment in the otherwise black and white film in which paintings of The Temptation of St. Anthony. Both American and European artists participated, including Ivan Albright, Eugene Berman, Leonora Carrington, Salvador Dalí, Paul Delvaux, Max Ernst, O. Louis Gugliemi, Abraham Rattner, Horace Pippin, Sydney Spencer, Leonor Fini and Dorothea Tanning. All artists who submitted a painting received $500, while the winner received a prize of $3000. Max Ernst won the competition and his painting was shown in the film. Dali’s entry also became famous in its own right.

The competition was judged by Marcel Duchamp, Alfred H. Barr, Jr., and Sidney Janis. Max Ernst wining submission was not loved by all as the film critic Bosley Crowther of The New York Times called Ernst’s painting “downright nauseous” and wrote that it “looks like a bad boiled lobster.

Of her work and the meaning behind the depiction Dorothea Tanning wrote:

“…It seems to me that a man like our St. Anthony, with his self-inflicted mortification of the flesh, would be most crushingly tempted by sexual desires and, more particularly, the vision of woman in all her voluptuous aspects. It is this phase which I have tried to depict in my painting. St. Anthony, alone in the desert, struggles against his visions; half-formed, moving in indolent suggestion, colored with the beautiful colors of sex, his desires take shape even in the folds of his own wind-tossed robes…”

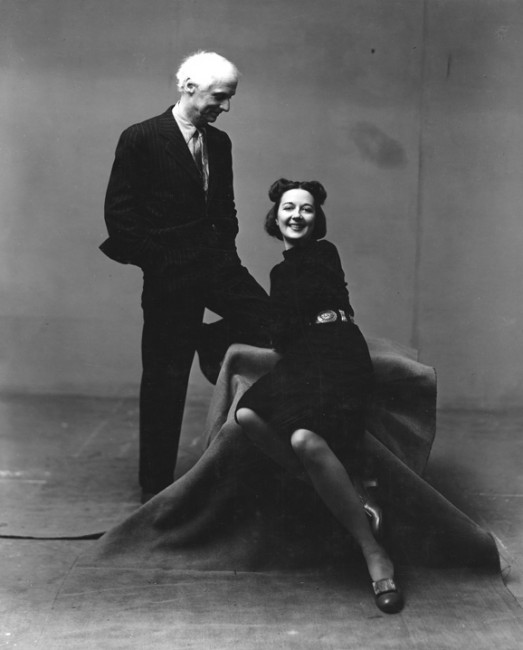

A photographer took a picture of Dorothea whilst she was working on the St Anthony portrait as a promotional photograph for the Bel Ami competition. It was at a time when she had been ill and had contracted encephalitis and the photographer had to prop her up for the shot as she was so unwell. She has her back to us but we see her long flowing locks of hair and on the wall is her famous Birthday self-portrait. In her autobiography, Between Lives, she tells of how the illness caused her and her soon-to-be husband Max to return to the peace of Sedona in 1946 and sub-let their New York apartment to their friend, Marcel Duchamp. Dorothea and Max married in October 1946. Although they had regular guests come to their Sedona home, Dorothea always maintained that the period in Sedona, when it was just her and her husband, were the happiest days of her life.

The newlywed couple would separately paint all day and then come together in the evenings to listen to music, read and often play chess which was one of their favourite pastimes.

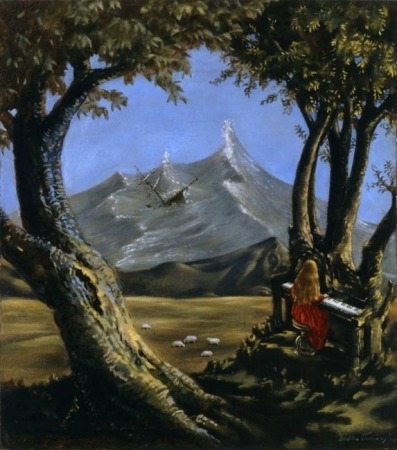

Their love of chess is depicted in Dorothea’s 1947 work entitled Max in a Blue Boat. It depicts the couple in the boat in the midst of a desert landscape and they seem to move effortlessly despite the lack of water.

In 1947 Dorothea completed the work entitled Maternity, which focused on motherhood and the psychological and physical problems associated with bearing and raising a child. In the setting of a sand-strewn desert we see a young woman holding a young child in a shielding encirclement. At the feet of the woman, on the rug, lies her dog which has a child’s solemn face staring out at us. The features of the dog resembled her own Lhasa Apso dog, named Katchina. Mother, child and dog make for a strong family unit set against a hostile setting.

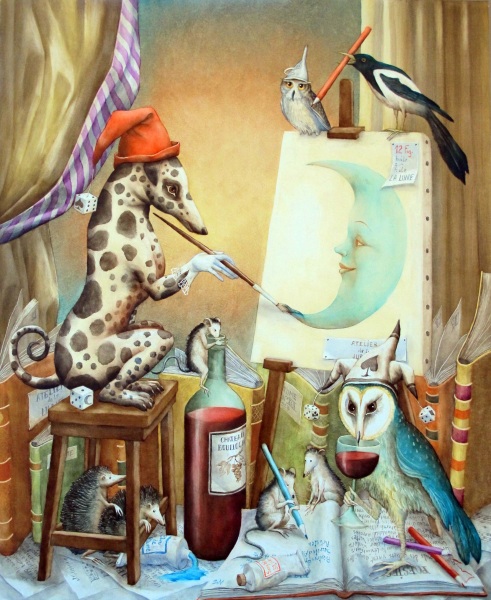

The dog was depicted in one of her favourite works entitled Tableau Vivant. It was then purchased by the National Galleries of Scotland. The painting was the first by Dorothea Tanning that they had acquired and joined up with major artworks by Surrealists Leonora Carrington, Salvador Dalí and René Magritte held at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art (SNGMA). The work was first shown at Tanning’s first exhibition in France in May 1954 at the Galerie Furstenberg, Dorothea Tanning: Peintures 1949-1954. She had inscribed the title L’Etreinte on the verso, which can be translated as The Embrace. A few months later the inscription was crossed out and substituted with Tableau Vivant and it was under its new title, Tableau Vivant that it was included in the artist’s first exhibition in Britain, at the Arthur Jeffress Gallery, London in 1955.

It was not uncommon for Surrealist artists to include animals in their paintings. Numerous Surrealist artists took animal embodiments which played the role of their alter-ego in their work: Max Ernst used a bird, Leonora Carrington favoured a horse; and Tanning took Katchina. Whreas other Surrealist depicted various types of the animal, Tanning’s choice was more specific. It was her own pet, Katchina, whose insertion into Tanning’s work was not of necessity a personification of the artist; sometimes it acted as a witness, other times as a protagonist, the Katchina affected different roles in different works. These works started a change of Tanning’s painting style. She moved away from the meticulous, controlled, illustrative technique which was the hallmark of her Surrealist work. In its place she began to decide on much looser, softer, more painterly brushwork and her colour switched from bright, intense primaries to ashes and ochres. It was a move towards her Abstract period.

The painting is a depiction of many feelings. Power, love, the erotic, the humorous, the dream and the nightmare, Tableau Vivant brings together many key moments in the artist’s life and career. Tanning loved the painting and it was included in almost every major exhibition of her work, notably her solo shows in Brussels in 1967, Paris in 1974, and the Malmö Konsthall and Camden Art Centre in 1993. The work of art remained with her for the remainder of her life until 2012, when she died at the age of 101, almost sixty years after painting it. Towards the end of her life, she specified it as one of a small number of works reserved only for sale to a museum. Simon Groom, Director of Modern and Contemporary Art at the National Galleries of Scotland said of the painting:

“…We’ve been looking for a major painting by Dorothea Tanning for many years. This was one of her favourite works: she kept it for more than sixty years, hanging it above her desk in her apartment in New York. It’s a stunning addition to the Galleries’ world-famous collection of Surrealist art…”

Sarah Philp, Director of Programme and Policy at Art Fund, which helped the National Galleries of Scotland financially with the purchase of the work which cost £205K said:

“…Tableau Vivant is an astonishing work with a fascinating biography and we are proud to help National Galleries of Scotland purchase this painting for their outstanding Surrealist art collection…”

The Tableau Vivant dog appeared in a number of her paintings after 1946, including Interior with Sudden Joy.

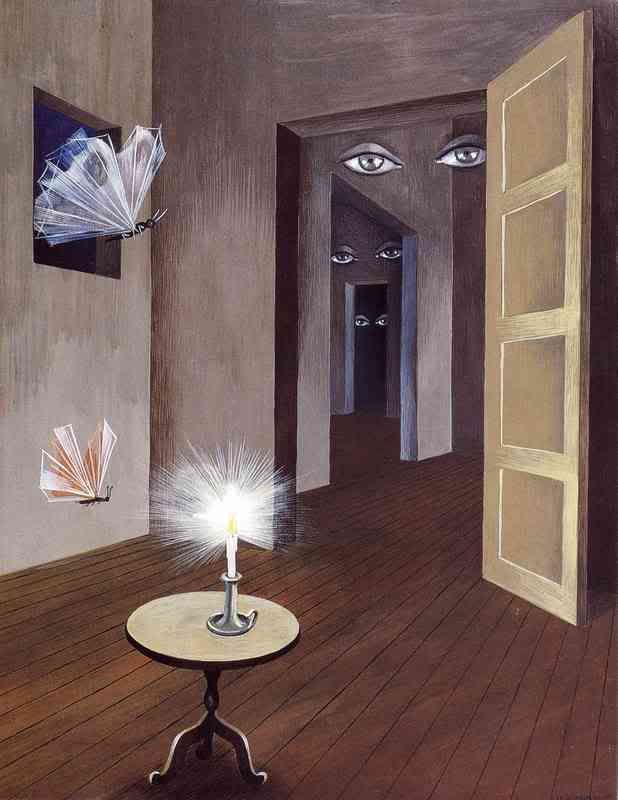

Interior with Sudden Joy is a strange painting. In the depiction we see two girls standing to the right. They strike a provocative pose. They are both dressed in white garments which harmonise with their pale skin, the buttons are unfastened and expose a camisole top and red bra, which reminds one of the bared chest in Tanning’s self-portrait Birthday. The girls pose with their arms wrapped around each other and both exude an air of nonchalance. They are young women and are only too aware of their sexuality. The girl furthest to the right pats the head of a large shaggy dog. The dog, which faces away from us, takes little notice of the two girls and instead stares at the blackboard on the back wall like a pupil ready to learn. On the blackboard there is chalked writing. In her memoir, Tanning says she took writings written in poet Arthur Rimbaud’s ‘secret notebooks’ and put them on the blackboard in this painting. Rimbaud was admired by the surrealists because of his belief that poetry passed through the body in the manner of a musical instrument, which reaffirmed the surrealist idea of automatism as a creative outlet using the body as a vehicle.

On the floor, close to the feet of one of the girls, lies a burning cigarette. The girl’s hand is held up as though the cigarette had once been held between her fingers. To the left of them is a naked boy embracing a strange amorphous mass which imitates a human figure and wraps itself around him. The whiteness of its fabric-like flesh contrasts with the boy’s dark skin, and abundance of dark curls which form a halo around the boy’s head. The boy looks completely at peace. If the painting’s title Sudden Joy derives from any part of the depiction it is from him. In her memoir, Tanning described the girls as being like Sodom and Gomorrah. On the floor in the left-hand corner of Tanning’s painting is an open book atop an ornate purple cushion. Its pages are blank, perhaps waiting to be written in. It is an eerie depiction. We see a figure standing in the doorway in the left-hand top corner of the painting, and the black door stands ajar waiting for someone or something to enter the room.

Dorothea Tanning died on January 31st 2012, at her Manhattan home at age 101. Her husband Max Ernst had died thirty-six years earlier.

Most of the information in my blogs about Dorothea Tanning come from the excellent 2020 biography of the artist, entitled Dorothea Tanning: Transformations by Victoria Carruthers.

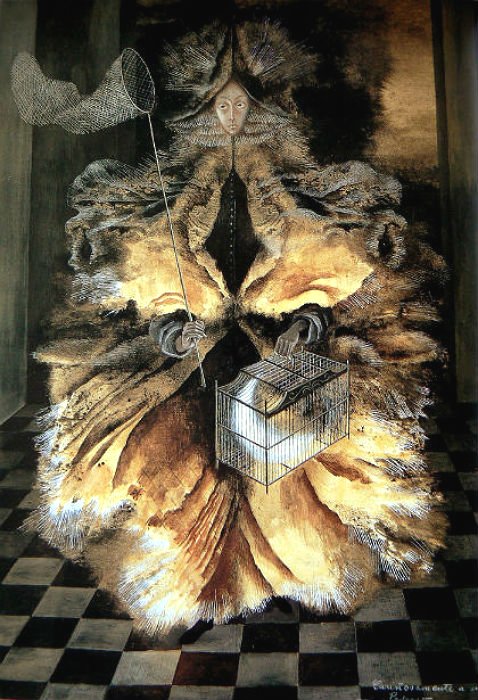

In 1958, Remedios Varo participated in the First Salon of Women’s Art at the Galerías Excelsior of Mexico, together with Leonora Carrington, Alice Rahon, Bridget Bate Tichenor and other contemporary women painters of her era. Remedios submitted two of her works, Harmony and Be Brief, and won the first prize of 3,000 pesos.

In 1958, Remedios Varo participated in the First Salon of Women’s Art at the Galerías Excelsior of Mexico, together with Leonora Carrington, Alice Rahon, Bridget Bate Tichenor and other contemporary women painters of her era. Remedios submitted two of her works, Harmony and Be Brief, and won the first prize of 3,000 pesos.

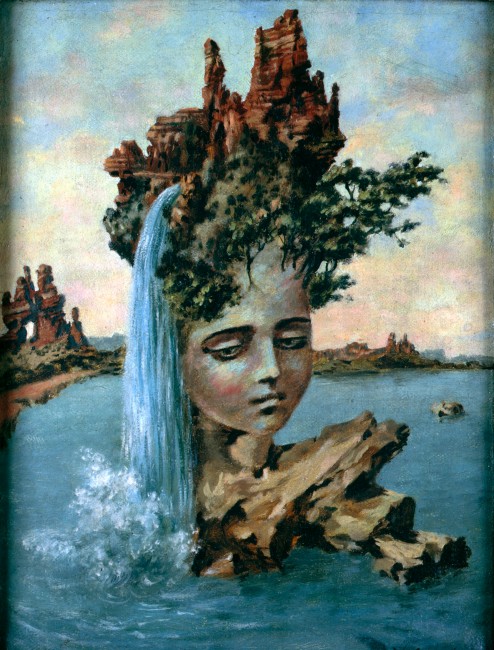

If you look closely at the chest cavity of the figure you will detect the circle of yin-yang, the Chinese symbol that similarly represents the balance of opposites. The face of the figure is one of calmness and serenity and suggests inner harmony and balance.

If you look closely at the chest cavity of the figure you will detect the circle of yin-yang, the Chinese symbol that similarly represents the balance of opposites. The face of the figure is one of calmness and serenity and suggests inner harmony and balance.

In 1963 Remedios suffered some health problems. She had complained of a shortage of breath when climbing stairs. She had a history of chronic gastric problems and was known to drink excessive amounts of coffee as well as being a heavy smoker. She was checked out for heart problems but was given a clean bill of health. The state of her mental health was open to doubt. Some of her friends said she was bubbly and full of life whist others said she had told them that she was depressed and did not know whether she could carry on with life. Walter Gruen, her husband, remembered the devastating afternoon of October 8th 1963, saying that he and Remedios had lunched with their friend Roger Cossio who had come to buy Varo’s painting, The Lovers. Gruen said his wife was happily explaining the details of the work to the buyer. With lunch over Cossio left and Gruen returned to his Sala Margolin shop across from their house to do some work. Shortly after, their Indian maid rushed into Gruen’s shop to tell him that Remedios was very ill. Gruen rushed home to find his wife complaining of chest pains. Gruen was unable to contact a doctor so left Remedios and went into the next room to consult some medical books. When he returned to his wife, he found that she had died.

In 1963 Remedios suffered some health problems. She had complained of a shortage of breath when climbing stairs. She had a history of chronic gastric problems and was known to drink excessive amounts of coffee as well as being a heavy smoker. She was checked out for heart problems but was given a clean bill of health. The state of her mental health was open to doubt. Some of her friends said she was bubbly and full of life whist others said she had told them that she was depressed and did not know whether she could carry on with life. Walter Gruen, her husband, remembered the devastating afternoon of October 8th 1963, saying that he and Remedios had lunched with their friend Roger Cossio who had come to buy Varo’s painting, The Lovers. Gruen said his wife was happily explaining the details of the work to the buyer. With lunch over Cossio left and Gruen returned to his Sala Margolin shop across from their house to do some work. Shortly after, their Indian maid rushed into Gruen’s shop to tell him that Remedios was very ill. Gruen rushed home to find his wife complaining of chest pains. Gruen was unable to contact a doctor so left Remedios and went into the next room to consult some medical books. When he returned to his wife, he found that she had died.

In her early days in Mexico, Remedios did few paintings and spent most of her time writing. She and Leonora Carrington would write fairy tales, collaborated on a play, invented Surrealistic potions and recipes, and influenced each other’s work. The two women, together with another of their friends, the photographer Kati Horna became known as “the three witches”

In her early days in Mexico, Remedios did few paintings and spent most of her time writing. She and Leonora Carrington would write fairy tales, collaborated on a play, invented Surrealistic potions and recipes, and influenced each other’s work. The two women, together with another of their friends, the photographer Kati Horna became known as “the three witches”

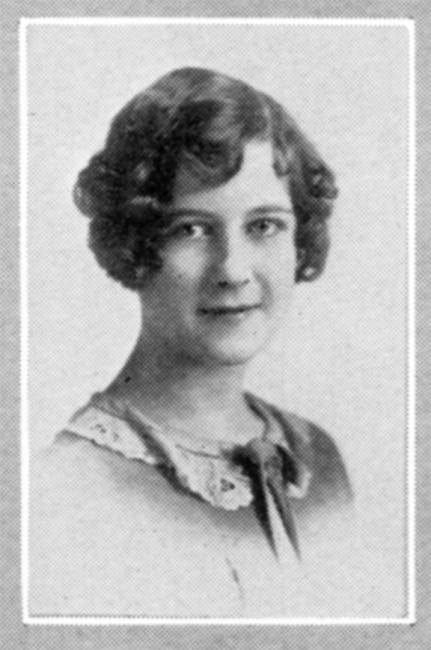

The founder of the Surrealist movement was the French poet and critic André Breton who launched the movement by publishing the Surrealist Manifesto in 1924 and led the group till his death in 1966. Surrealist artists find magical enchantment and enigmatic beauty in the unexpected and the strange, the overlooked and the eccentric. In a way, it is a belligerent dismissal of conservative, if somewhat conformist, artistic values. The depictions in the Surrealist paintings are startling often colourful. In some ways they are mesmerising and one wonders what was going through the mind of the painter when they put their ideas on canvas or wood. My featured artist today is French and she was considered to be one of the leading twentieth century French Surrealist painters. Let me introduce you to Agnès Boulloche.

The founder of the Surrealist movement was the French poet and critic André Breton who launched the movement by publishing the Surrealist Manifesto in 1924 and led the group till his death in 1966. Surrealist artists find magical enchantment and enigmatic beauty in the unexpected and the strange, the overlooked and the eccentric. In a way, it is a belligerent dismissal of conservative, if somewhat conformist, artistic values. The depictions in the Surrealist paintings are startling often colourful. In some ways they are mesmerising and one wonders what was going through the mind of the painter when they put their ideas on canvas or wood. My featured artist today is French and she was considered to be one of the leading twentieth century French Surrealist painters. Let me introduce you to Agnès Boulloche.