Sky, Setting Sun, Bushes in Foreground. by Eugène Boudin (ca. 1848-1853)

One of Boudin’s earlier paintings which featured his mastery of depicting skies is his work entitled Sky, Setting Sun, Bushes in Foreground which he completed in the early 1850’s. In this work, Boudin has gone for a very high frame and in fact, the sea does not appear in the composition. In this work and many similar ones, there is just the faint outline of a low horizon. More often than not, the clouds are the main, sometimes the only motif. At times, the subject becomes so fine or abstract that Boudin specified its meaning on the back of the work. His love of the paintings by the Dutch Masters made Boudin strive to achieve skies that he had seen in their works of art. Between 1850 and 1870 Boudin completed many such depictions and a note in his personal diary refers to them:

“…To swim in the open sky. To achieve the tenderness of clouds. To suspend these masses in the distance, very far away in the grey mist, make the blue explode. I feel all this coming, dawning in my intentions. What joy and what torment! If the bottom were still, perhaps I would never reach these depths. Did they do better in the past? Did the Dutch achieve the poetry of clouds I seek? That tenderness of the sky which even extends to admiration, to worship: it is no exaggeration…”

On January 14th, 1863, Boudin married the 28-year-old Breton woman Marie-Anne Guédès in Le Havre and the couple set up home in Paris but would return to the Normandy coast in the summers.

On the Beach at Trouville by Eugène Boudin (1863)

Boudin had started off his career painting seascapes, but he found his calling in the 1860’s depicting small beach scenes which he populated with affluent holidaymakers that had made the journey from Paris and outlying places. These people spent summers sampling the health-giving benefits of sea bathing and the vibrant social life in the fast-emerging seaside resorts of Trouville and Deauville. Boudin created a few hundred examples of this type of painting, which enhanced his reputation. He knew that genre was popular with the public once writing:

“…I shall do something else, but I shall always be a painter of beach scenes…”

On the Beach, Dieppe by Eugène Boudin (1864)

An example of this type of work is his 1864 painting entitled On the Beach, Dieppe. The setting is the beach of the Channel coastal town of Dieppe.

The changing skies of France’s Channel coast and the fashionable crowds on the resort beaches were Boudin’s lifelong subjects. These pictures were avidly collected, ensuring the artist’s success. In 1863 he commented:

“…They love my little ladies on the beach, and some people say that there’s a thread of gold to exploit there…”

On the Beach, Sunset by Eugène Boudin (1865)

Around 1865 Eugène Boudin spent time painting on the Normandy coast along with Monet, Courbet and Whistler. It is around this time that Boudin began a series of depictions of fashionable beaches and this was to carry on for the whole of that decade. In his 1865 painting, On the Beach, Sunset, we see the well-dressed upper-class holidaymakers who have gathered together to catch the final light of the day. The seaside towns of Trouville and Deauville had not only their beautiful sandy beaches to inveigle tourists to their town but also had racetracks and casinos to satisfy those who liked the thrill of a wager.

Princess Metternich on the Beach by Eugène Boudin (1867)

Visits by famous people to the Normandy beaches, such as Napoleon III’s wife, the Empress Eugénie also enhanced their reputation. Another dignitary to visit the Normandy beaches was Princess Metternich, the famous Austrian socialite, and wife of the Austrian ambassador to France and one of the most notable women at the court of Napoleon III. She visited the seaside times on many occasions and was often accompanied by Princess Eugénie. Her visit was captured by Boudin in his small 1867 painting entitled Princess Metternich on the Beach. The Impressionistic style of the painting gives us little idea of the woman herself, which may be a relief to the Princess, as commentators of the time described her as small, very slight of build and as having “a turned-up nose, lips like a chamber pot and the pallor of a figure from a Venetian masque”.

Laundresses by Eugène Boudin

For a period of time in 1867 Boudin left the beaches of Normandy and the luxurious lifestyle of the visiting rich and depicted the less well-off peasants and their daily routines. Boudin could clearly see and understand the difference in the lives of the various social classes. Did this bother him? In a letter to his friend Ferdinand Martin, on August 28th, 1867, he condemned the social class system, writing:

“…I have a confession to make. When I came back to the beach at Trouville it seemed nothing more than a frightful masquerade. If you have passed one month among the people condemned to hard work in the fields, with black bread and water, and you then find that gang of golden parasites with such a triumphant air, you can’t help feeling a bit of pity. Fortunately, dear friend, the Creator has spread a little of his splendid and warming light everywhere, and what I reproduce is not so much this world as the element that envelops it…”

…….and yet in a letter to the same friend, Ferdinand Martin, a year later (September 3rd. 1868), he justifies his depictions of the wealthy on the Normandy beaches, writing:

“…The peasants have their painters, Millet, Jaque, Breton; and that is a good thing. Well and good: but between you and me, the bourgeois walking along the jetty towards the sunset, has just as much right to be caught on canvas, ‘to be brought to the light’. They too are often resting after a day’s hard work, these people who come from their offices and from behind their desks. There’s a serious and irrefutable argument…”

The Franco-Prussian War broke out in July 1870 and the Prussian army invaded the French capital the following month. Both Boudin and Monet fled the country with Monet going to London whilst Boudin went north to Belgium and the city of Antwerp. Whilst in Antwerp Boudin completed a number of maritime paintings, one of which was his 1871 work entitled Antwerp, Boats on the Scheldt.

Another work around the same time was The Escaut River in Antwerp.

With the Franco-Prussian war ending in 1871 and the bloody Paris Commune, which followed in the Spring of that year, coming to an end, it was safe to return to France.

Portrieux, in the bay of St. Brieuc, Côtes du Nord, was a popular village with painters and Boudin visited it on several of his trips to Brittany between 1865 and 1897. His 1873 painting Low Tide, Portrieux depicts vessels he would have seen during his visits. In this painting Boudin has focused on the fishing vessels from Newfoundland, the Terre-Neuvas, becalmed at low tide, and several of his paintings centred on this subject matter. Boudin, who was the son of a ship’s captain, and who had worked as a cabin boy on ships sailing along the Channel coast, was well able to recognise, and record, the individual characteristics of the vessels he came across in the ports he visited.

The Dock at Deauville by Eugène Boudin (1891)

One of Boudin’s paintings, The Dock of Deauville, which he completed in 1891, has a similar depiction, ships in a harbour. This painting treats a common theme in Boudin’s later art, ships in harbours. For Boudin these paintings were all about tranquillity, harmony and the effect of natural light on subjects and, unlike other maritime painters, avoided depictions of busy dockside life and the arduous jobs carried out by dock workers. In this work, one can see how he has combined lighter tones around the ships’ masts, often overlying the darker lines of the wood and rigging with white or grey tones as if to suggest the passing wind and ever-changing positions which were everyday aspects of nautical life.

View of Antibes by Eugène Boudin (1893)

By the time the 1880’s came around Boudin had achieved widespread recognition as an accomplished painter and had finally achieved financial security once he had secured a contract with the art dealer Durand-Ruel. Paul Durand-Ruel, who was a great supporter of Impressionism and the Impressionist artists. In 1883 he opened his new gallery on the Boulevard de la Madeleine in Paris with an exhibition of works by Boudin, comprising 150 paintings and other pastels and drawings.

Fair in Brittany by Eugène Boudin

In 1888 at an auction at Hôtel Drouot in Paris, a large auction house in Paris, known for fine art, antiques, and antiquities, which consisted of sixteen halls hosting seventy independent auction firms, many of Boudin’s paintings were bought by avid collectors of his work.

Venice: Santa Maria della Salute and the Dogana seen from across the Grand Canal, by Eugène Boudin (1895)

In 1889, 1890, and 1891, more successful exhibitions were organized at Galerie Durand-Ruel, and in 1890 Boudin was elected a member of the Société des Beaux-Arts. His paintings travelled across the Atlantic and were shown in exhibitions in Boston in 1890 and 1891. He continued to exhibit at the Paris Salons until his death and received a third-place medal at the Paris Salon of 1881, and a gold medal at the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris. In 1892 Boudin was made a knight of the Légion d’honneur. His wealth allowed him to travel and he visited Belgium, the Netherlands, and southern France, and from 1892 to 1895 made regular trips to Venice.

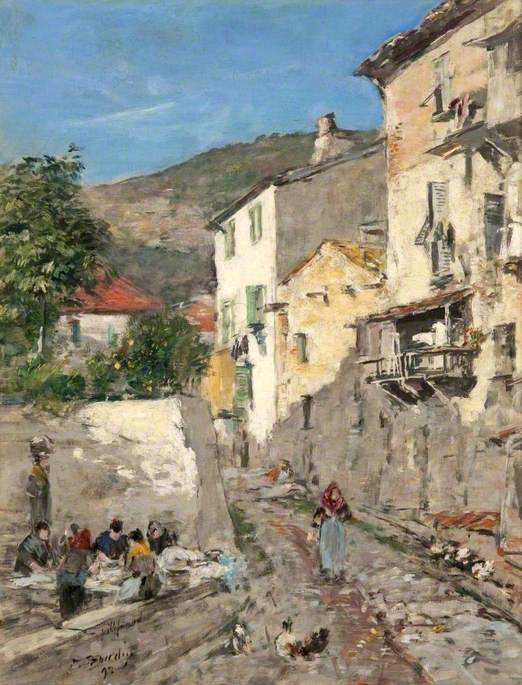

Villefranche by Eugène Boudin (1892)

Boudin was now spending every winter in the south of France, returning to his beloved Normandy in the summer. His wife died in 1889 and Boudin’s own health was in decline. In 1898 Boudin must have realised he was dying as he decided to move back to his home in Deauville to die.

Eugène Louis Boudin died on August 8th 1898 aged 74. He was buried according to his wishes in the Saint-Vincent Cemetery in Montmartre, Paris. Boudin was a very modest man and once said:

“…I may well have had some small measure of influence on the movement that led painters to study actual daylight and express the changing aspects of the sky with the utmost sincerity…”

But I will leave the last words to Claude Monet who said of Boudin:

“…If I have become a painter, I owe it to Eugène Boudin…”