The Early Years

Anna Richards (c.1885)

My featured artist today is Anna Richards Brewster, the much-admired American Impressionist painter who was one of the most successful women artists of her time and yet her name has largely been forgotten. Anna was born in the Germantown neighbourhood of Philadelphia in 1870. She was the sixth of eight children of William and Anna Richards.

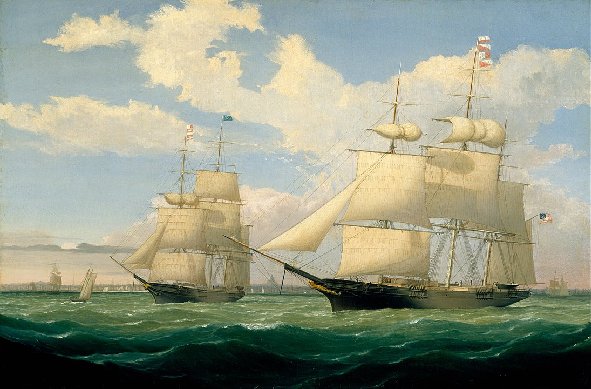

William Trost Richards

Her father was William Trost Richards, the American landscape artist, who was associated with both the Hudson River School and the American Pre-Raphaelite movement. After living most of his life in Pennsylvania, William Trost Richards rented a summer home in Newport, Rhode Island, and later built a summer home, Gray Cliff, on Conanicut Island in 1881, so as to be closer to the ocean. Richards was recognized by his colleagues as one of America’s foremost marine painters.

A Rocky Coast by William Trost Richards (1877)

Anna’s mother was Anna Matlack Richards, an intellectual Quaker from a prominent Philadelphia family. She was a children’s author, poet and translator best known for her fantasy novel, A New Alice in the Old Wonderland. Anna Matlack and William Richards married in 1856.

The 2009 edition of Anna Matlack Brewster’s book, A New Alice in the Old Wonderland.

Anna Matlack, as a young woman published fictional works, plays, and poems, including a fictional autobiography by “Mrs. A. M. Richards” with the title Memories of a Grandmother in 1854. After she married William Trost Richards they spent many years travelling abroad. In the 1890s, she published comic poems for children in the popular children’s magazines Harper’s Young People and The St. Nicholas Magazine. The success of these comics led her to publish A New Alice in the Old Wonderland in 1895, which featured illustrations by her daughter Anna. It is recognised as one of the more important “Alice imitations”, or novels inspired by Lewis Carroll’s Alice books.

Landscape with a Canal by Anna Richards Brewster (1887)

Anna Matlack Richards educated their children at home to a pre-college level in the arts and sciences and her son-in-law later wrote about his wife and siblings gaining knowledge from their mother’s teachings:

“… Besides the usual subjects, all of them knew something about art, literature and music; each played a musical instrument; and each was encouraged to follow some special interest and to understand and to care for excellence…”

Mentome France by Anna Richards Brewster

Between 1878 and 1880, the family lived in England, mainly in Cornwall and London, and for a short time in Paris, where Anna’s father found subjects for his painting and Anna would often accompany her father during his painting trips. Having returned to America, the family lived in Boston from 1884 to 1888 so that their son, Theodore, was able to attend Harvard University.

Country House near Exeter, England by Anna Richards Brewster

At the age of fourteen Anna exhibited at the National Academy of Design. Now living with her family in Boston, she studied with Dennis Miller Bunker at the Cowles Art School where he was the chief instructor of figure and cast drawing, artistic anatomy, and composition. In 1888 the school awarded her the first scholarship in Ladies Life classes.

Langdale Pikes by Anna Richards Brewster (1905)

From there, in 1890, Anna left Boston and went to New York to study at the Art Students League for a few months each winter beginning in 1889 and these annual trips continued until early 1894. Here she was tutored by William Merritt Chase, Henry Siddons Mowbray and John La Farge. In 1889 she won the Dodge Prize, worth $300, awarded by the National Academy for the best picture painted by an American woman of any age. The winning painting was entitled An Interlude to Chopin.

Near Williamstown Ma. by Anna Richards Brewster

Whilst in New York, she rented a room at Mrs. Jacobs’s boarding house, and it was here that one day she met Annie Ware Winsor, who taught at the Brearley School, a private school for girls in New York City. Winsor was five years older than Anna but they became life-long friends and intellectual soulmates. Annie Winsor, through her family’s connections, was able to inroduce Anna to many important and prominent families, such as the Vanderbilts and Schuylers.

Moulin Huet, Guernsey by Anna Richards Brewster

Annie and Anna both became members of the Social Reform Club, an organization for improving the conditions of the poor, and the Louisa May Alcott Literary Circle, where they read books and poetry. This allowed Anna to break away from the insular life of living with her family and the lack of any social interaction when living at home.

Portrait of the Artist’s Father by Anna Richards Brewster

Between 1890 and 1895, Anna once again went to Europe with her father and, like him, she managed to capture what she saw on canvas and in numerous sketch books. They travelled to various places in England, Ireland, Scotland and the Channel Islands. She even went to Paris where she studied at the Académie Julian with the French painters, Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant and Jean-Paul Laurens. Whilst at the family home in Boston she would receive private art lessons from LaFarge who was a friend of the family. She recounted in a letter to her friend Annie Winsor one such session:

“…The whole afternoon I was wrapped in the pleasure of admiration for Mr. LaFarge. Father and I agree that no mortal could have acted with more perfect courtesy, quietness and charm. I am very glad he came, though it wasn’t much of a lesson…”

Clovelly by Anna Richards Brewster

Anna was now in her early twenties and both her parents who had been backing her financially began to wonder when she would become a professional painter and earn her own living and they began to pressurise her. She had always had a difficult relationship with her father and mother. She was much closer to her father. Her father had been giving her lessons in art from an early age and had to critique her work which often led to many heated arguments. Anna would also have heated discussions with her mother who was both a serious scholar and a formidable woman. Her mother described Anna as “an uneasy household presence” and was tiring of her lack of future plans. In a letter Anna wrote to her friend Annie Winsor in September 1893 in which she recounted the words of her mother:

“…Mother said that if I was good for anything I should never have a pencil out of my hand, (that I should draw everything, anything) and think of nothing else. That I ought to read nothing, think nothing, write nothing…..Most people don’t have the physical strength or mental strength to concentrate themselves…….no other thing can attain perfection and perfection is the only thing that exists nothing else counts. I reject that doctrine but nevertheless it is not without effect but I don’t believe, won’t believe that to be a painter one must be a fanatic…”

Clovelly Village, England by Anna Richards Brewster (1895)

Anna had some exhibiting success during the early 1890s. She had exhibited and sold four of her paintings at the National Academy of Design in New York and in 1895 she illustrated two books for JD Lippinott, a family friend, who owned his own publication business. A decision was made in 1895 between twenty-five-year-old Anna and her parents. It was time for her to leave home and make a life for herself as an artist. She had made a number of trips to England with her father and he believed that it was there that his daughter could make a name for herself and make a living from her art. It was decided that she should head for the small, picturesque Devon coastal village of Clovelly.

Devonshire Farm House by Anna Richards Brewster

Anna remained in Clovelly for a year and then in 1896 moved to London where she and her parents agreed it would be an ideal place to show and sell her work. In 1896 she rented a studio and an apartment in Chelsea, where she lived for the next nine years. Whilst living in the English capital she sold a number of her paintings and exhibited four times at the Royal Academy. Thirteen of her paintings featuring life at Clovelly were even exhibited in Baltimore, Maryland. Her works were also shown at the National Academy of Design and at Knoedler Gallery in New York; and at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia. In England her work was on show at the Royal Society of Artists, in Birmingham and three times at the Royal Miniature Society.

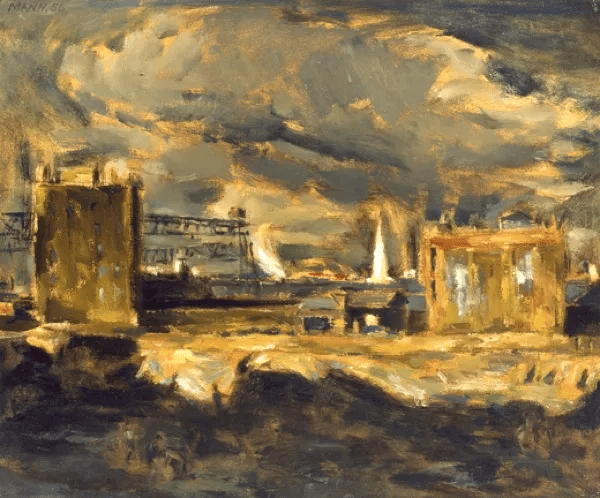

Battersea Bridge at Twilight by Anna Richards Brewster

On an earlier trip to London, Anna’s parents had become friends with an elderly couple, Mary and Henry Kemp-Welch, who were leading lights in the London art world and Mrs. Kemp-Welch became Anna’s patron and introduced her to many socially prominent families and from these introductions Anna received some portrait commissions.

A Summer Morning in London by Anna Richards Brewster

Anna’s living expenses had been met by her father whose financial situation had been sound due to the sale of his own paintings. He had also financially helped his other children. Anna must have been very conscious and somewhat felt guilty, about relying on her father for money and this is borne out in letter she wrote to her friend, Annie Winsor on August 28th 1900:

“…Money is the one thing I feel I have no control over whatsoever, and whose workings, bearings, laws, and significance I do not understand…”

And in another letter to Annie on November 29th 1900, she wrote:

“…My mind’s much occupied with the question of making money. I must … I shall never get any feeling of self-respect until I can support myself…”

Trafalgar Square London by Anna Richards Brewster

In 1900, Anna’s patron and friend Mrs Kemp Welch, now in old age, had become frail and she was advised by her doctors to leave England during the cold damp winter months and move to a warmer climate. Anna had a lot to be thankful for the elderly lady’s support and so offered to accompany her to Italy as her chaperone. She had a lot to do before she could leave London and one can tell the pressure she was under as one notes a letter she sent to Annie Winsor prior to her departure. She wrote:

“…Next Tuesday, Mrs. K-W (who is far from well) and I start for Italy for her health; and before then I have to rent my flat . . . finish my academy pictures, ditto a portrait, ditto some work for Mr. Holiday [a stained-glass artist], give my five pupils their last lessons…”

Italian Gardens at Mount Vesuvius by Anna Richards Brewster

Anna and Mrs Kemp Welch did get to travel to Italy in December 1900. That month had been a sad period for Anna as she received news of her mother’s death, aged 66. It had not been altogether a shock to Anna as her mother had been diagnosed as having breast cancer two years earlier and she was later diagnosed as being terminally ill. Anna’s mother was adamant that her daughter remained in England and not come back to America. She had visited her daughter in London in October 1900, two months before her death. On December 22nd 1900 Anne wrote to her friend Annie Wintor telling her about that last meeting she had with her mother:

“…Yes, it is a great happiness that – just lately, she and I got a restful feeling of mental understanding, more than ever before….I got to say what I had been longing to – that whatever happened I could always feel that now we understand each other, and that all misconceptions were past……She grew so much in those years from the moment when she learned of her mortal malady, and met the knowledge with all the bigness of her soul…. I felt nearer to her than I ever had. She has grown more human and beautiful to the end…”

……….to be continued.

Some of the information was gleaned from the usual search engines but most came from a 2008 book entitled Anna Richards Brewster, American Impressionist which was a collection of essays edited by Judith Kafka Maxwell with contributions from Wanda Corn, Leigh Culver, Judith Kafka Maxwell, Susan Brewster McClatchy and Kirsten Swinth.