After my last two blogs looking at the exquisite artistry of the American landscape painter, Frederic Church, I am going to give you something completely different today. I was going to facetiously say that I was moving from the sublime to the ridiculous but I know that labelling Surrealism as “ridiculous” is a rather facile and childish statement. Not being an artist, I would be curious to know if the upbringing of an artist and how life has treated them has any bearing on their painting style. For example, Frederic Church came from a happy and financially sound family background and lived close to a very picturesque countryside and in some ways the works he produced mirrored not just the environment around him but the peace and tranquillity of his mind. My featured artist today probably felt little of that peace and tranquillity in his life and that may account for some of the disturbing images he produced. My artist today is André Masson and the painting of his I want to look at is entitled Gradiva which he completed in 1939. It is not just about a painting but about a German novel and a renowned Austrian neurologist who was hailed as the founding father of psychoanalysis and along the way I will delve into the world of automatism in art!

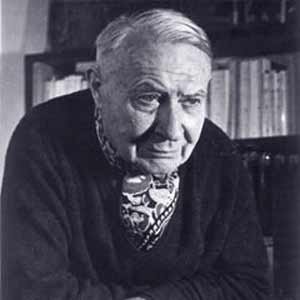

Andre Masson was born in January 1896, in Balagny-sur-Thérain, in the northern French province of Oise, about sixty miles north of Paris. Although born in France, because of his father’s business, he spent most of his childhood in neighbouring Belgium. The family relocated to Lille in 1903 and then later moved to the capital Brussels. In 1907, aged 11, he enrolled at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts et l’École des Arts Décoratifs in Brussels where he received tuition from the Belgian painter and muralist, Constant Montald, who would later teach the likes of Rene Magritte and Paul Develaux. It was on Montald’s advice that Masson decided to leave Belgium and travel to France. In 1912, Masson moved to Paris and attended the illustrious Parisian art college, École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts where he attended Paul Albert Baudoin’s studio to study fresco painting. In 1914 he was awarded a scholarship from the École des Beaux-Arts and this allowed him to travel to Italy, along with his fellow art student, Maurice Albert Loutreuil. Whilst in Italy, Masson studied the art of fresco and discovered the works of Paolo Uccello.

These were exciting times for the youth of the day. Art Nouveau, Impressionism and Symbolism were dominating the art scene and the music of Wagner and the thoughts of Nietzsche were often foremost in their minds. Like many of his fellow art students of the time, André was a person who railed against convention and authority and had many run-ins with the police. He embraced vegetarianism and would often be seen walking bare-footed along the streets. He avidly read the great works of literature and philosophy and became a follower of the German poet and philosopher, Friedrich Nietzsche.

In 1914, France entered the First World War and there was a call to arms. Many of the young eagerly put themselves forward to support their country. Some, like Masson, looked on the fight that lay ahead in terms of a grand Wagnerian battle with little concern about their own mortality. In an interview he gave the American magazine Newsweek in 1965 André Masson said that when war was declared he volunteered because he wanted to experience “the Wagnerian aspects of battle”. Like many who marched off patriotically to the front line, they were mere “cannon fodder” and would never return home. Although Masson, an infantryman, was not killed in the war, in April 1917, he was badly injured during the Second Battle of the Aisne when several French army battalions stormed the German lines on the Chemin des Dames ridge. (It is interesting to note that one of the German soldiers at this battle was Adolph Hitler!)

The battle was short-lived and, for the French, it ended catastrophically in a matter of a few weeks. Thousands of French troops were slaughtered. Many others mutinied and the career of the French army’s Commander-in Chief, Richard Nivelle was destroyed. The attack, which Masson had taken part in proved disastrous and he was gravely wounded and lay helpless on the battlefield all night and it was not until the following day that stretcher bearers were able to reach him and take him to a field hospital. The wound to his chest and abdomen was of such severity that Masson remained in hospital for the next two years. Not only did he suffer horrendous physical injuries but the battle and his witnessing the death and maiming of many of his colleagues left him mentally scarred and he had to undergo a long period of psychiatric rehabilitation to treat the devastating effect it all had on his mind. His patriotic rush to serve his country resulted in constant physical pain, nightmares and insomnia for the rest of his life and he was advised by psychiatrists to stay away from the noise and chaos of cities.

In April 1919 Masson went to Céret, a town which lies in the Pyrénées foothills in south-west France. Céret was, around this time, a popular meeting place for artists, such as Picasso, Modigliani, Andre Derrain and Matisse. Whilst living there Masson met Odette Cabale, who became his wife. Odette became pregnant and Masson decides to return to Paris where his parents could assist her. In 1920 their daughter Lily was born. Masson sets up a studio at 45 Rue Blomet in Paris which soon became a local meeting place for aspiring artists as well as some influential people such as the author Ernest Hemmingway and the writer and art collector Gertrude Stein.

In 1924 the German-born art historian, art collector and art dealer, Daniel-Henri Kahnweiler, organised Masson’s first solo exhibition at his Galerie Simon. One of the viewers at the exhibition was André Breton and he bought a work by Masson entitled The Four Elements. Breton was the founder of the Surrealist Movement and later that year published Manifeste du surrealism, his Surrealist Manifesto, in which he had defined surrealism as “pure psychic automatism”. Masson, who had been invited to join Breton’s group of Surrealists, was influenced by the ideas Breton had put forward and began to experiment with “automatic drawing” or automatism. Automatism was a way of creating drawings in which artists smother conscious management of the movements of their hand, and by doing so, allow their unconscious mind to take over. Breton and his Surrealists believed automatism in art was a higher form of behaviour. For them, automatism could express the creative force of what they believed was the unconscious in art. Masson’s work could be categorised as a semi-abstract variety of Surrealism, which is experimental use with unusual, such as sand. His so-called sand pictures were works which his automatic drawing would be first put on the canvas using glue. Then before the glue had dried he would sprinkle coloured sand over it. The canvas would then be shaken and the sand would only remain on the glue. One of his most famous and most successful “sand paintings” is Battle of the Fishes, which he completed in 1926 and is now housed in the MOMA in New York. I read a piece about this work which described it as:

” a work which a primordial eroticism is revealed through an imagery of conflict and metamorphosis, poetically equating the submarine imagery with its physical substance…”

Is that how you see it ????????

In 1925, Masson participated in the first Surrealist exhibition, at the Galerie Pierre, alongside Picasso, Ernst, Klee, Man Ray. However, André Masson fell out with Breton and his Surrealists mainly due to Breton’s authoritarian leadership of the group and his dogmatic attitude. Masson also came round to the fact that automatism was becoming too much of a constraint on his art and so in 1929 he severed ties with the group. It was that same year that Masson and his wife Odette parted company after almost ten years of marriage.

Masson spent some time in the Provencal hills around the town of Grasse, where he met Matisse. In 1934 Masson returns to Paris but that February he is alarmed by the right-wing Fascist riots which take place in the city that February. He decided to flee the turmoil that has beset the French capital and headed south to Spain and the city of Barcelona. He was accompanied by Rose Maklès, sister of the wife of his best friend and the well-known author Georges Bataille. In December 1934 André and Rose married in Tossa de Mar on the Costa Brava, and in June 1935 their son Diego was born, later, in September 1936. a second son Luis was born. Masson’s decision to relocate to Spain, to avoid the chaos of riots in Paris, was an unfortunate one as in October 1934 the Spanish city was hit by a violent insurrection of its people and Masson and his family became trapped in a friend’s house which was at the heart of the city and which was being subjected to constant shelling and sniper fire. This was just the scenario his psychiatrists had told him to avoid when he was discharged from hospital at the end of the First World War. The situation deteriorated further in 1936 with the start of the Spanish Civil War and Masson and his family quickly headed back to France. His return to France also coincided with his return to the Surrealist fold as he and André Breton settled their differences and the following January, Masson exhibited works at the Surrealist Exposition of Paris which was held at Georges Wildenstein’s Galérie Beaux-Arts.

The year 1939 was marked by the start of the Second World War and in January 1940 the German army marched into Paris. Masson found himself in a precarious situation. His artwork had already been deemed as degenerate by the Nazis. The Nazis looked upon the Surrealist Movement and its artists as having close ties to the Communists and to top all that, Masson’s wife Rose was Jewish. He realised that for he and his family, in order to survive, had to flee France. From Paris they headed south to Auvergne and then on to Marseille. Here a group of Americans led by Varian Fry, a journalist, had set up a European Rescue Committee which helped Jews and Germans blacklisted by the Nazi authorities to escape to the USA. Varian Fry hid the refugees at the Villa Air-Bel, a chateau on the outskirts of Marseille and then took them via Spain to neutral Portugal, or shipped them from Marseille to Martinique and from there on to the USA, which was Masson escape route.

André Masson and his family, along with some of his artwork, landed in America in 1941 and one would think that his troubles were over but alas the US Customs thought differently as when they examined his drawings they declared five of them to be pornographic and tore them to pieces right in front of the artist’s eyes !!! For a short while he lived in New York before moving to Connecticut. In 1945, with the war over, the Masson family returned to France, where they lived for a while with his wife’s sister, Simone. In 1947 they moved to the small town of Le Tholonet, which lies close to Aix-en-Provence in southern France. He continued to paint and received many lucrative commissions including one from the French Culture Ministry to paint the ceiling at the Parisian Théatre Odéon. A series of solo and retrospective exhibitions of his work are held all over Europe and America. He visited Rome and Venice in the 1950’s and from these trips, he produced a beautiful series of coloured lithographs of Italian landscapes.

Masson’s wife Rose died in August 1986 and Masson himself died in Paris in October 1987 aged 91.

The painting of André Masson I have chosen today is entitled Gradiva which he completed in 1939. So who is Gradiva? Gradiva, is Latin for “the woman who walks” and in the Vatican Museum, there is a Roman bas-relief (a projecting image with a shallow overall depth), of Gradiva. This sculpture depicts a young robed woman who we see raising the hems of her skirts so as to be able to stride forward at pace. This sculpture was the basis for the novel written by the German author Wilhelm Jensen, entitled Gradiva. He originally published his fictional tale, it in a serialised form, in the Viennese newspaper, Neue Freie Presse in 1902.

It is the story of Norbert Hanold, a young archaeologist who became totally obsessed with a woman who did not even exist. He had visited the Vatican museum when he was struck by the beauty of a bas-relief of young Roman woman, very light on her feet, whom he baptized “Gradiva” (she who walks). He purchased a reproduction of the sculpture, which he hung on the wall of his workroom. He becomes fixated by the image and mystery of this enigmatic young woman. One night he dreams that he is in Pompeii in AD 79, just before the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius. There he meets Gradiva. He desperately tries to warn her about the horrific events that are about to occur, but he finds himself powerless to rescue her. After waking, he is overcome by the longing to meet Gradiva. He immediately sets off for Pompeii, where he meets a young woman, very much alive, whom he believes is Gradiva. In the course of the meetings that follow, he tries to rationalise his fixation for the girl by interpreting signs such as the fact that Gradiva appears at noon, the ghost hour, and other such signs. Gradiva, in turn, seeks to cure him by gradually revealing her identity to him. Through this adventure, Norbert finally sees Gradiva for who she really is: his neighbour and childhood friend Zoe Bertgang (“Bertgang” is the German equivalent of “Gradiva”), who also travelled to Pompeii. For years he had not seen her and had no desire to see her, but without realising it Norbert was still in love with her and he had substituted his love for Zoe with his love for Gradiva, the young woman of the bas-relief. Happily, his fixation for Gradiva finally yields to reality, and Norbert is cured.

In 1906, Sigmund Freud had been made aware of this story by Carl Jung , who believed Freud would be interested in the dream sequences of the story. Freud, who frequently cited his Interpretation of Dreams which he published in 1900, suggested in his review of Jensen’s novel that even dreams invented by an author could be analyzed by the same method as real ones. He fastidiously analyzed the two dreams which were the basis of Jensen’s story, and linked them to happenings in Norbert’s life. By doing this Freud attempted to demonstrate that dreams were substitute wish fulfilments and established that they constituted a return of the repressed. According to the pschoanalysist, the source of Norbert Hanold’s fixation was his repression of his own sexuality, which caused him to forget, his past love, Zoe Bertgang, in order to keep him from recognizing her. This he termed as “negative hallucinations”. Freud concluded that the way Zoe treated Norbert when they met in Pompeii was in the manner of a good psychoanalyst, cautiously bringing to consciousness what Norbert forgot through repression.

As an interesting footnote to the Freud story, four months after he published his essay on Gradiva and Jensen’s story, he visited Rome and during the trip he went to see the bas-relief representing “Gradiva” at the museum of the Vatican, the very same one that had inspired Jensen to write his story. Just as Norbert Hainold, the character in Jensen’s story had done, Freud bought a copy of the bas-relief of Gradiva and hung it in his office in Vienna, at the foot of his divan. There it remained until he left Vienna, and took it with him to London in 1938, where it can be found on the wall of his London study which forms part of the Freud Museum.

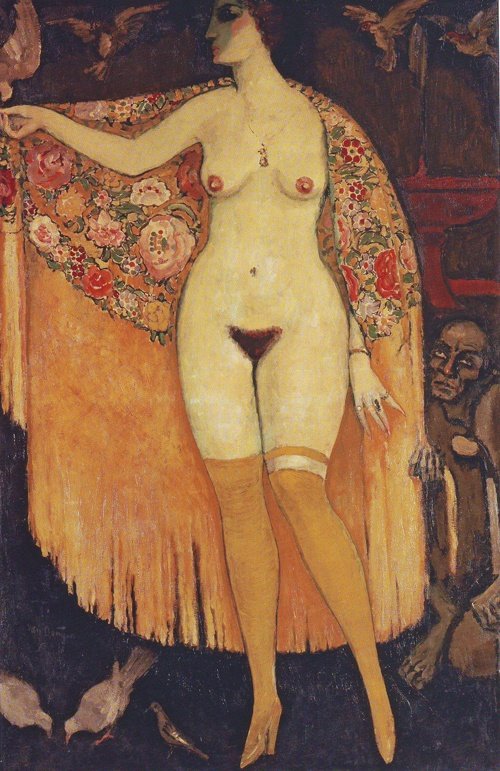

In today’s featured painting, Masson iconography for Gradiva (The Metamorphosis of Gradiva) is a Freudian illustration drawn directly from the Jensen story. In the painting we see a large woman, half flesh, half marble sprawled on a marble plinth, the base of which is starting to crumble. Her legs are splayed apart and between them we see a beef steak and a gaping shell-like vagina. To the right of her, on the wall in the background, we see the erupting volcano. To the left of her we see a large crack in the side wall signifying that the building she is in, is about to collapse. Another strange addition to the painting is a swarm of bee-like creatures which seem to swarm in arc-like fashion behind the figure of the woman, similar to the arc formed by the way her marble arm arches over her head. Why depict bees? The whole of the painting is bathed in a flickering reddish light which highlights a clump of poppies which can be seen in the left foreground of the work. I have tried to explain some of the iconography of this painting but I will leave you to try and figure out if there are more hidden meanings to what you see before you.

Finally for those of you who would like to read the complete version of Wilhelm Jensen’s Gradiva then you can get a copy from Amazon.com:

http://www.amazon.com/Gradiva-Pompeiian-Fancy-Classic-Reprint/dp/B0094OOP36

or Amazon.co.uk:

I must apologise for the length of this blog but once I got started researching the life of the painter, the painting itself and the story of Gradiva I was loathed to cut anything out. Not being a master of the art of précising, I don’t think I would make a good journalist !!!!!