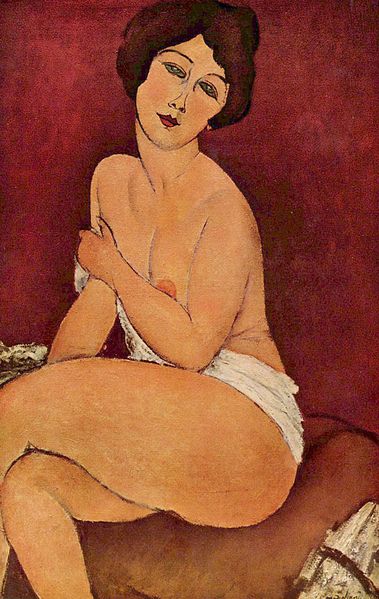

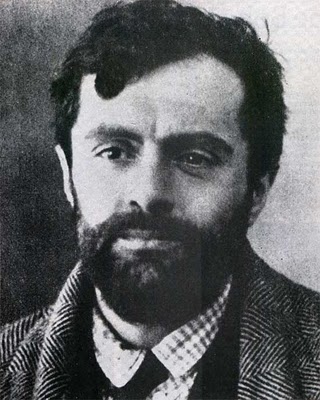

Today’s blog is the final one of four about the life of Amedeo Modigliani, the Livorno-born artist, who at the age of twenty-two moved to Paris where he lived out the last fourteen years of his life. As an artist he employed a number of models for his works of art and like many artists of the time the relationship between artist and model became much more than just a working relationship. Mothers were horrified if their daughters agreed to model for the artists, as an artist’s model was looked upon as just being one step from being his lover and thus the artist model was accused of almost prostituting herself in the name of art. It is almost certain that Modigliani had very close and intimate relationships with his models as he believed, in the case of his female nude portrayals, to achieve a great painting he had first to make love to the model ! I wonder if that is how he sold that argument to the model !!! However one must remember that Modigliani for all his faults and transgressions was an extremely handsome man. Although the models, who sat for his nude collection, are unknown we do know that he had intimate and serious relationships with three named women and it is those ladies, who featured in many of his works of art that I would like to highlight in today’s blog.

In 1910, whilst living in Paris, Modigliani met Anna Akmahtova. Anna was born Anna Gorenko, in Odessa in 1889, and was five years younger than Modigliani. She came from a well-to-do family and from an early age was fascinated by poetry. Her love of poetry was denounced by her parents as being foolish, self-indulgent and something which would they feared would have a corrupt influence on their daughter. However she persisted and started writing poetry when she was just eleven years of age and had her first works published when she was seventeen. She would become one of Russia’s greatest twentieth century poets.

The one person who constantly encouraged Anna to write her poetry was the young Russian poet, Nikolay Gumilev. However, to placate her parents all her writings were published under her pseudonym, Akhmatova, which was the surname of her maternal grandmother. After a prolonged “chase” Nikolay finally persuaded Anna to marry him but in a letter to her friend she outlined how she was unsure that she had made the right decision. She wrote about her feelings for her future husband:

“…He has loved me for three years now, and I believe that it is my fate to be his wife. Whether or not I love him, I do not know, but it seems to me that I do…”

The couple were married in Kiev in April 1910. Her family were totally against the marriage and refused to attend the service. The young couple left Russia and travelled to Paris for their short honeymoon and it was then that she met and became a friend of Amedeo Modigliani, who like her, had a love of poetry. Modigliani was undoubtedly attracted by her beauty as well as her poetry. She was slim and elegant and everywhere she went in Paris, men’s heads would turn to admire her good looks. Her husband was unimpressed by this attention and especially with the attention Modigliani gave his wife. Anna returned to Russia with her husband but she and Modigliani continued to correspond for the next twelve months. He was obsessed with her. His letters to Anna became ever more intense and passionate and Anna recalled her short time with him during her honeymoon and their correspondence. In a letter to a friend, she wrote:

“…In 1910, I saw him very rarely, just a few times. But he wrote to me during the whole winter. I remember some sentences from his letters. One was: Vous êtes en moi comme une hantise (You are obsessively part of me). He did not tell me that he was writing poems…”

In 1911 she returned alone to Paris and met up with Modigliani and this was the start of a short but passionate love affair. Their affair had to remain a secret. She dared not be seen in public with Modigliani in the guise of his lover in case word of it got back to her husband in Russia. The affair lasted just two months and Anna returned to St Petersburg and her husband and never saw Modigliani again.

The second lady with whom Modigliani had an affair was Beatrice Hastings. Beatrice was born in London in 1879, and was five years older than Modigliani. She was the fifth of seven children. Her real name was actually Emily Alice Haigh, but she used Hastings as her pen name. Her father was John Walker Haigh, a Yorkshire wool trader. He and his family immigrated to South Africa in the 1880’s. Beatrix was a writer, poet and literary critic, and wrote extensively for the weekly British political and literary magazine, New Age. During her life, she had a number of lovers, both men and women. She was a fiery and self-willed character and in her youth caused her parents innumerable problems. She was briefly married to Alexander Hasting, whom she said was a boxer. Although a headstrong person she was also very able and was a talented singer and a gifted pianist. She moved to Paris in April 1914 as a correspondent for the New Age journal, just before the onset of the First World War. She contributed a regular column until 1916, entitled Impressions de Paris, which went down well with the English public who wanted to know about the bohemian lifestyle of the Parisian literati and the bohemian lifestyle of the Montmartre artists.

Beatrice first set eyes on Modigliani in July 1914 when she was in the Café Rosalie in Paris. Later she was introduced to him by a mutual friend, the sculptor, Ossip Zadkine, at La Rotonde café, which was situated in the Montparnasse Quarter of Paris. It was a famous café, opened in 1911 by Victor Libion, and was a favourite haunt of the aspiring writers and artists of the time, such as Picasso and Diego Rivera. In her memoirs, Beatrix recalled those first meetings with Modigliani. She wrote:

“…A complex character. A swine and a pearl. I sat opposite him. Hashish and brandy. Not at all impressed. Didn’t know who he was. He looked ugly, ferocious, greedy. Met him again at the Café Rotonde. He was shaved and charming. Raised his cap with a pretty gesture, blushed to his eyes and asked me to come and see his work And I went. He always had a book in his pocket. Lautremont’s Maldoror. The first painting was of Kisling. He had no respect for anyone except Picasso and Max Jacob. Detested Cocteau. Never completed anything good under the influence of hashish…”

Modigliani was thirty and she was thirty-five when they first met. He was down on his luck, almost penniless despite his mother still sending a monthly allowance but which was frittered away on alcohol and drugs. The sale of his paintings had almost dried up and what he did sell went for a few francs. His former patron Paul Alexandre, an avid buyer of his work, had gone to fight at the Front and at this time, he had nobody to promote or sell his art.

Beatrice and Modigliani had a stormy love affair, which was to last until 1916. In 1915 Modigliani moved in to Beatrix’s flat in the Rue Norvain which was on the Butte Montmartre. In those two years they were together, Beatrice became Modigliani’s favourite model and he immortalised her in many of his paintings.

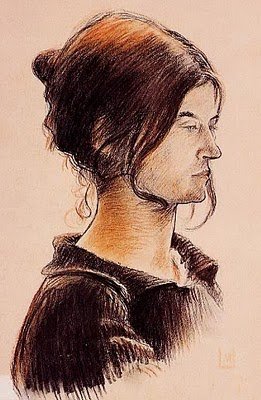

Modigliani’s final love affair was with Jeanne Hébuterne. Jeanne was born in Paris in April 1898 and was fourteen years younger than Modigliani. Her elder brother André was an aspiring artist and he introduced Jeanne to many of the artists who lived around Montparnasse, some of whom she modelled for. Following her own desire to become an artist she enrolled in 1917 at the Académie Colarossi and it was whilst studying at this establishment that she was introduced to Modigliani. If nothing else, Modigliani was a woman’s man who had a certain magnetism and charisma which charmed the females he encountered. She was nineteen and he was thirty-three. She was a very beautiful young woman with the most amazing almond-shaped eyes. She was slim, pale-skinned and had long light-brown braids. Jeanne soon fell under his magical charm and before long, the pair became lovers. They were very much in love and after a short while, she moved in to his lodgings on Rue de la Grande Chaumière. Her parents, who were staunch Catholics, were horrified with this turn of events – their daughter had taken up with a penniless artist, shared his bed and to make things worse he was Jewish.

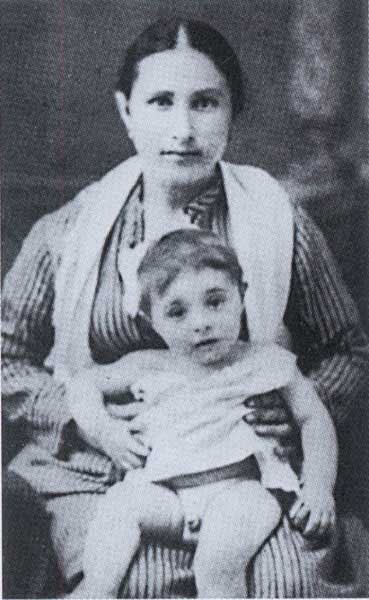

Jeanne was all Modigliani could ask for. Besides her beauty which he admired, she seemed to be his soul mate. For her it was a case of “unconditional love”. She asked for very little in return from Amedeo and she put up with his excessive drinking. In 1918, despite the terror of the First World War, Jeanne became pregnant. If the horrors of war and being pregnant were not enough of a burden, Modigliani’s health was in decline. It was fortuitous that two years earlier Modigliani had struck up a friendship with a Polish émigré and small-time art dealer Léopold Zborowski. The art dealer had initiated a deal with Modigliani, that in return for his paintings, he would provide him with comfortable lodgings and studio space. Now in 1918, Zborowski once again came to Modigliani’s rescue by arranging for him and Hébuterne to leave Paris and go to the warmer climes of Provence in Southern France and it was here on November 29th 1918, in the town of Nice that Jeanne gave birth to Modigliani’s daughter, Jeanne.

Modigliani, Jeanne and their daughter returned to Paris in the Spring of 1919 and that summer Jeanne became pregnant once again. In August of that year Modigliani was supposed to have gone to London to be present at an exhibition of some of his work but by then he was much too ill to travel. Although he continued to paint, it was becoming increasingly more difficult as he would frequently have to stop to lie down and rest. Eventually by the end of 1919 he was bed-ridden. On January 22nd 1920 he was found unconscious in the apartment and was rushed to the pauper’s Hôpital de la Charité. Two days later he died. The medical report stated that he choked on his own blood. The official cause of death was tubercular meningitis. Reputedly his last words harked back to his love for the country where he was born. His dying words being:

“…Italia, Cara, Italia…”

The year before his death

His girlfriend, Jeanne Hébuterne,whom he had promised to marry, and who was eight months pregnant with Modigliani’s second child was inconsolable. She had been staying at her parents’ apartment whilst Modigliani was in hospital and her loss was so great that at 3am the day after her lover had died, she threw herself out of her parents’ fifth floor apartment window, killing herself and her unborn child. Her parents had her buried in a grave in the Paris suburb of Bagneux with little ceremony, mortified and embarrassed at the life she had led with Modigliani and the way in which she had decided to end her own life. Modigliani’s mother was unhappy that her son and the mother of his child were not at rest together and fought hard for this to be achieved. Modigliani’s mother was also adamant that Jeanne’s daughter should be recognised as her son’s child.

After three years of arguing with Jeanne’s parents, the body of Jeanne Hébuternes was exhumed and laid to rest in Modigliani’s grave at the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris and their daughter, Jeanne Hébuternes, who by this time was three and a half years old was recognised as Modigliani’s daughter, took his surname and inherited her share (one-fifth) of the proceeds from the sale of his paintings. The dealers retained four-fifths!

Having read so much about Modigliani I have tried hard not to be too judgemental. It would be easy to say that he brought about his own downfall with his extensive use of drugs and bouts of heavy drinking but I think we need to look more carefully at his physical state before we pass judgement. From his pre-teens days we know he had been unwell with pleurisy and later tuberculosis. Tuberculosis at the time was a killer disease which was highly infectious and one train of thought is that Modigliani’s use of drugs and alcohol was not only to ease his suffering but was to mask his illness. Unfortunately we are only too well aware how one can become drug and alcohol dependent and that, as was the case of Maurice Utrillo who had suffered a similar addiction due to mental issues, happened to Modigliani who had become totally reliant on alcohol and drugs.

I have enjoyed looking at all Modigliani’s paintings and despite some who believe his drug and alcohol abuse added to his artistic talent I believe that had he been a well man, drug and alcohol-free, and lived longer, then who knows what masterpiece.

For those of you who would like to read more about Modigliani, try looking at these websites:

http://www.geni.com/people/Olimpia-Lumbroso-Modigliani/6000000014620610421

http://chez-edmea.blogspot.co.uk/2010/11/jeanne-hebuterne.html#.UjAUzn80QWf

http://artinthestudio.blogspot.co.uk/2011/04/modigliani-part-two.html

http://www.bonhams.com/auctions/11174/lot/53/

http://secretmodigliani.com/bio2.html

http://ineedartandcoffee.blogspot.co.uk/2010/10/cubisms-birthplace-bateau-lavoir.html

http://www.abcgallery.com/M/modigliani/modigliani10.html

http://www.modigliani-drawings.com/paul_alexandre.htm

http://www.modigliani-drawings.com/Introduction.htm

http://www.artandantiquesmag.com/2011/02/modigliani-finds-a-dealer/