Self Portrait (1901)

I went to the Summer Exhibition at the Royal Academy one afternoon, a couple of weeks ago and frankly I was a little disappointed in the majority of the works. Yes they were quirky and often bizarre but I like beauty in paintings. Maybe part of the problem was that in the morning I had just visited the National Portrait Gallery and perused their permanent collection as well as the BP 2014 Awards exhibition. There were so many beautiful works of art. There was a “chalk and cheese” difference between the paintings I stood before at the Portrait Gallery and those in the many rooms housing the Royal Academy’s summer exhibition. You see, I like to stand back from a work of art and be amazed at what I see before me. I especially like to be stunned by the beauty depicted by the artist whether it is a landscape or a portrait. I am never impressed by a few random blobs of colour on a canvas and to be told to just imagine something. Yes, I do need to be led by the nose and have everything explained to me through a realistic depiction. The artist I am featuring today was also an admirer of beauty, to be more precise, feminine beauty and I was utterly seduced by a painting he completed featuring his lover, a work which the establishment at the time found a little too much to countenance. Today I am going to look at the life of Théodore Casimir Roussel, and explore some of his paintings and prints and feature his sitter, studio assistant and lover, Hetty Pettigrew who featured in many of his works.

Roussel was born in the French town of Lorient in Brittany in March 1847 and was educated in France. He was called to arms by his country during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 but in 1878 he moved to England and settled in London. Two years later he married an English lady, Frances Amelia Smithson Bull. Roussel had always loved to sketch and paint and was, for the most part, self taught. When he settled in the English capital he managed to secure studio space in Chelsea with two English artists, George Percy Jacomb-Hood and Thomas Henry. A couple of years after working in his Chelsea studio, Roussel began to exhibit some of his paintings. His breakthrough came in 1885 when he was introduced to one of his neighbours, the successful artist, James McNeil Whistler, who had seen Roussel’s paintings and had been very impressed by the standard of his work. Despite Whistler being thirteen years older than Roussel, it was not long before the two became firm friends, probably because some of their works of art centred around the same subject matter – London and the Thames river. They also shared similar artistic tastes and had similar views with regards the art establishment. Roussel now became one of Whistler’s London circle of friends which included Walter Sickert, Paul Maitland and Wilson Steer. Like Whistler, Théodore Roussel became a member of the Royal Society of British Artists in 1887 but both resigned from the Society the following year.

Some of Roussel’s early work, when he was in London, depicted the river Thames around Chelsea. One such painting was Blue Thames. End of a Summer Afternoon, Chelsea received excellent reviews when it was exhibited at the London Impressionist exhibition. In December 1888 he exhibited seven such oil paintings of “Impressions of the Thames and Chelsea” at the London Impressionist Exhibition at the Goupil Gallery.

Another work featuring the Thames is a work Roussel completed later in his career was a work entitled The Thames at Hurlingham. This atmospheric work has all the characteristics of a Whistler painting. When Roussel made preliminary sketches for this work he was probably in the grounds of the famous Hurlingham Club, one of Britain’s greatest private members’ club which borders the Thames at Fulham. In the painting we are treated to the merest glimpse of the river and the house on the opposite bank as we peer between the two mature lime trees whose size has cast the bank in deep shadow.

(1886–7)

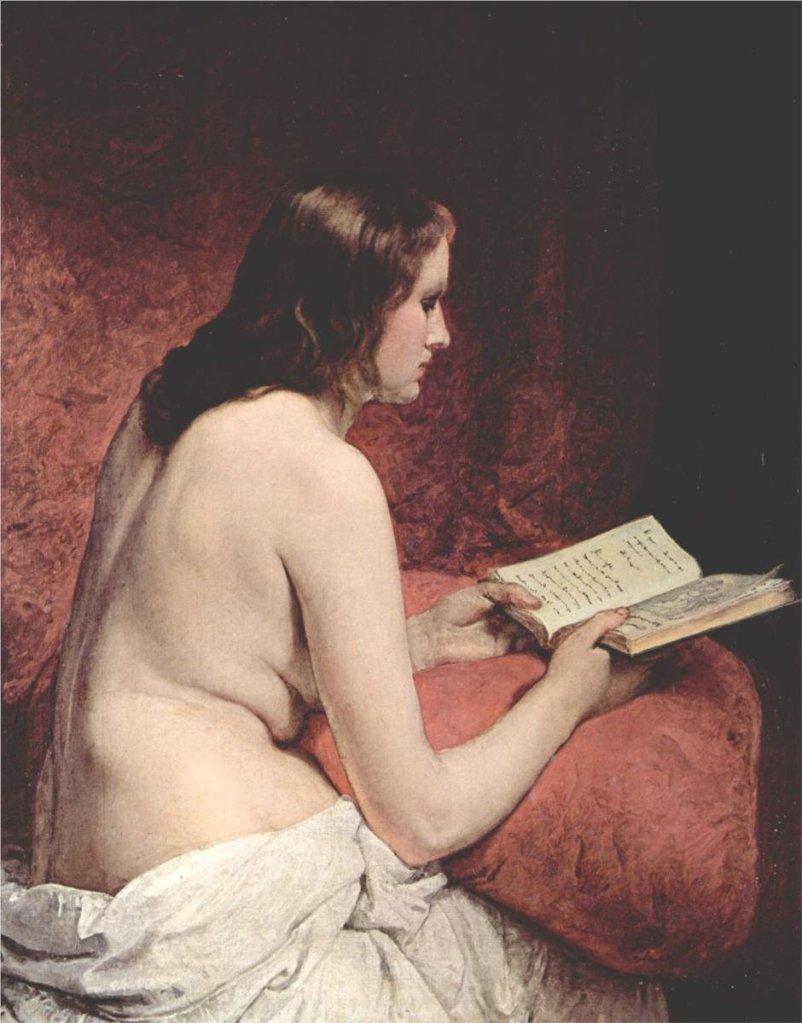

However my lead in to this blog was all about Roussel’s depictions of female beauty and one particular painting which had caught my attention and so let me feature this absolute gem. The painting I am referring to was completed by Roussel in 1887 and was entitled The Reading Girl. It measures 152 x 161cms (60 x 64 inches) and now hangs in the Tate Britain in London and I urge you to feast your eyes on this beautiful work.

Roussel decided to by-pass the Royal Academy and exhibited this work in April 1887 at The New English Art Club, which had been founded in London in 1885 as an alternate venue to the Royal Academy for artists to exhibit their works. Maybe the reason for the painting being accepted into the exhibition was that this art club was, at that time, promoting the French style of painting. Maybe another reason for Roussel’s decision not to submit it to the Royal Academy was that he was well aware that the Royal Academy would be very critical of his depiction of a nude woman, not as a mythological, classical or historical character, but simply as a present day female. This was Roussel pushing the boundaries. This was a step too far for many and the art critic for the Spectator newspaper in the April 16th edition of the journal wrote a highly critical article. He wrote:

“…Our imagination fails to conceive any adequate reason for a picture of this sort. It is realism of the worst kind, the artist’s eye seeing only the vulgar outside of his model, and reproducing that callously and brutally. No human being, we should imagine, could take any pleasure in such a picture as this; it is a degradation of Art…”

It could well be that Roussel was making a stand with regards female nudity and would have been well aware of the furore which followed Edouard Manet exhibiting his famous but rebellious nude work, Olympia, at the Paris Salon twenty-two years earlier (see My Daily Art Display October 12th 2011).

What I suppose strikes you at first glance is how relaxed the sitter is for the artist, how comfortable and at ease she was to sit before Roussel without any vestiges of clothing. The female is Harriet (Hetty) Selina Pettigrew, a nineteen year old professional model, Roussel’s studio assistant and possibly a student of his. She was born in 1867 in Portsmouth, one of twelve children, nine brothers and three sisters. She was Roussel’s favourite model and also modelled along with her sisters Rose and Lily, for James McNeil Whistler, John Everett Millais and other Pre-Raphaelite artists. Hetty had met Roussel in 1884 and from becoming his model, then, despite Roussel being married, became his mistress and gave birth to their daughter, Iris around 1900. When Roussel’s wife died, instead of legalising his relationship with Hetty and their child, he married Ethel Melville, the widow of the Scottish watercolour painter, Arthur Melville. Once Roussel re-married in 1914, Hetty never sat for him again. Their close bond was over.

Look how Roussel has used an almost black background so that nothing detracts from the female form. This is not a pulchritudinous depiction of a classical woman à la Rubens. This is simply a modern beautifully proportioned young woman. Hanging from the back of her chair is a kimono which harks back to Roussel and Whistler’s love of all things Japanese which were sweeping through Europe. The female reads a newspaper giving the impression that before us, we have a well educated young woman. This is no Rococo-style air-head !! The art critic Frederick Wedmore’s view of the painting was completely at odds to that of the Spectator’s art critic. Of the painting he compared the work with many previous classics and wrote in the Art Journal of 1909:

“…the most health-suggesting, health-breathing of Courbets, with the most rosily robust of Caro Delvaille’s (Le Sommeil fleuri), with the dreamiest Henner, with the slimmest and least material of Raphael Collin’s (Floréal)… a high masterpiece… austere in its performance, restful in its effect…”

Eva Mongi-Vollmer an art historian and curator at the Städel Museum in Frankfurt commented on the pose of the woman in Roussel’s painting in her book, Naked!Woman views. Painters intentions departure to modernity. She wrote:

“…It is the reading of an intellectual, modern woman who is not sexually available, despite the nudity…”

Another of Roussel’s works which is believed to have featured Hetty is Study From the Nude of a Girl Lying Down, a drypoint completed around 1890 which is part of the collection at the Art Institute of Chicago with a print of it held at the British Museum.

My third and final featured work by Théodore Roussel which featured Hetty is Chiaroscuro, A Profile, the Golden Scarf, which he completed around 1900.

Théodore Roussel died at St Leonards on Sea, a coastal town in East Sussex in 1926, aged 79.