In the later part of the nineteenth century, Ring concentrated on landscape painting. For Ring, painting landscapes allowed him, through the works, to communicate and find expression in the world around him. One example of this is his 1888 landscape painting entitled The Road at Mogenstrup, Zealand. Autumn. This depiction is evidence that he was fond of muted autumn colours and there is a definite hint of melancholia about the depiction which may have mirrored his mood at the time.

A similar type of “drab” work is his 1901 painting entitled Thaw. The dilapidated fence in the foreground renders the depiction even more gloomy as does the artist’s use of yellowish-brown colours. It is yet another example of what one critic called Ring’s “landscapes of the soul”— a type of psychological painting with its own poetic soberness. Ring landscapes project his personal emotions. His friend and biographer Peter Hertz, a Danish art historian and museum worker, wrote how Ring, especially in those periods from 1887 to 1893 when his depressive moods and melancholy were prevalent, discovered a way of liberating himself, by painting his many overcast and misty landscapes. Hertz wrote:

“…With such weather he has closed himself up inside his own loneliness and found a resonance in nature, echoing his own mood… In these scenes of dull, overcast weather he reaches his highest pinnacle, giving most of himself…”

Laurits Rings was in a very bad place mentally in 1892. He had broken off all contact with Alexander Wilde and his wife Johanne. He had suffered the heartbreak of his mother dying and the sudden death of his brother, Ole. These losses made him doubt his belief in God and with this doubt came another doubt, a doubt in his own artistic ability and is hope that the lot of the peasant workers would be addressed came to naught.

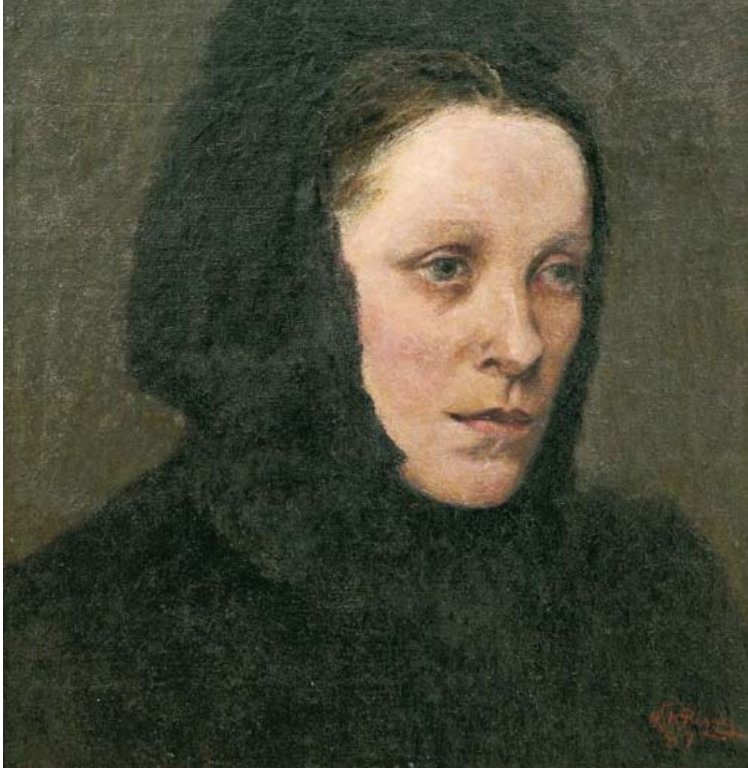

Salvation came to him in the form of a ceramicist, Henrik Kähler, who owned a Danish ceramics factory. Kähler Keramik was based in Næstved on the island of Zealand. He had started to experiment with more appealing designs with glazed finishes and in 1886, he succeeded in attracting a number of well-known artists to complement his designs. Laurits Ring was one as was his friend Hans Andersen Brendekilde. Through his relationship with Henrik Kähler, Laurits met his daughter, Sigrid who was also a painter as well as a ceramicist. Sigrid Kähler was the third woman who took on a special importance in Rings’ life.

She was literally his lifesaver. Friendship between them soon changed to mutual love and the couple married on July 25th 1896. Laurits was 42 and Sigrid was 21. The couple moved to a house in the harbour town of Karrebæksminde on the south-east coast of Zealand.

Sigrid featured in many of Laurits’ paintings. In his paintings of Sigrid we can depict subtle symbols of love and affection and the use of soft hues are different from his more melancholic ones he used in his Realism works. One depiction of Sigrid was his 1898 work entitled At the Breakfast Table. We see his wife seated at the breakfast table reading Politiken, the Danish daily broadsheet newspaper, which is Laurits’ way of reminding us about the world outside. The scene is lit up by the streams of sunlight which come in through the open door, and if we look outside, we can make out the lush green of summer.

Sigrid also featured in her husband’s 1897 work entitled In the Garden Door: The Artist’s Wife. The painting is housed in the Statens Museum for Kunst (SMK), National Gallery of Denmark and has proved to be one of the most loved works on show. Peter Nørgaard Larsen Chief Curator, Senior Researcher at SMK says of the work:

“…It’s one of my favourite pictures, and there are several reasons for that. It is fantastically nice painted and has a very crisp and delicate colour scheme. And then it’s a picture you’ll be happy to look at. This is the summer we dream of with a fertile garden and a beautiful woman. After all, this is the woman he just married, so he’s obviously interested in portraying her as part of a world he experiences as happy. A very positive picture…”

So, is this just a depiction of his wife, Sigrid, pregnant with their first child, Ghitta Johanne, who stands before a beautiful Spring garden scene which symbolises a consummated and fertile love between the artist and his wife? Is this simply a painting honouring fertility and the up and coming new life? Or is there something else we should be contemplating as we look at the painting. Remember Laurits Ring was, besides a man dedicated to Social Realism depictions, also a Symbolist painter. Let us look a little closer at the depiction. His wife stands before us on the patio with her belly bulging with her unborn child. This is about new life. Compare that with the potted bush by her side. It looks stunted being confined to the pot. Its branches are gnarly and old. In all, it looks as if it is coming to the end of its life. The depiction is a comparison of new life and death. It is a painting depicting transience and in some way a reminder that all things come to an end. It is Ring’s appreciation that the opposite to life is death. Ironically the painting is somewhat premature as Sigrid did not give birth to her daughter until January 5th 1899 !

In 1901 Ring produced a painting featuring his wife, Sigrid and their two-year-old daughter Ghitta.

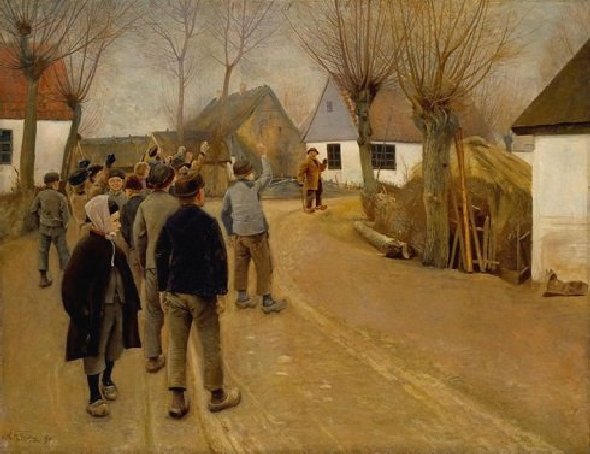

For me, his Social Realism art is his best genre. In 1890 he completed a work entitled The Drunkard. It depicts a group of angry villagers, fist-waving and shouting at an elderly man with a walking cane, some distance from them. He has been forced back to the edge of the village by the baying crowd. He has been isolated. It is a sign of rejection. However, it is not what we perceive it to be. The scene is actually part of a children’s social play. It is all about rejection and isolation of a lone figure at the hands of an unsympathetic group. The artist is testing us to think about times when we have shown little sympathy towards our fellow human beings. He wants us to examine our own conscience. The painting sadly verifies Ring’s pessimistic view of the human race.

On October 9th, 1900, Laurits and Sigrid’s second child was born, a son Anders Herman, who became a painter, silversmith and sculptor. The family moved to the old school in Baldersbrønde near Hedehuse, where on August 6th, 1902, their third and final child, a son, Ole was born. He like his father would become an accomplished artist and well-known for his local landscape works.

Laurits Ring’s interest in politics and social issues was an ever theme in his paintings. An example of this is his 1895 painting entitled A Visit to the Shoemaker’s Shop. It depicts a politician from the Social Democratic Party who has called on a pair of cobblers hoping that he would secure their support. It was through Laurits’ political convictions and his social realism depictions of workers and peasants during the early industrialization in Denmark, that he played an important role in what was termed The Modern Breakthrough. Unlike many of his contemporary artists and writers, you have to remember that Laurits Ring was not from a comfortable middle-class or upper-class background but originated from an impoverished peasant farming background and as one reviewer noted in 1886:

“…One implicitly trusts that Ring truly knows the life he portrays…”

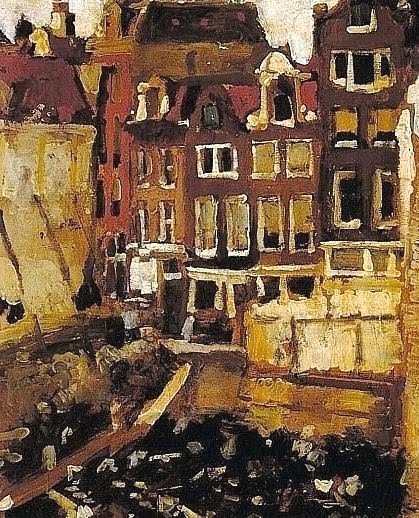

Another of Ring’s painting, from that year, which highlights the hard work of the less well paid is his depiction of drain-layers in his 1885 work, Laying the Drains. Laurits Ring was always sympathetic with the workers’ struggle for better living conditions and throughout his life he expressed respect for the poor. Ring was always careful to depict the everyday life among workers and rural people with dignity, and avoided sentimentality, choosing to highlight a realistic view of people’s lives, notwithstanding whether his subject was a poor farm couple or a pair of ditch diggers.

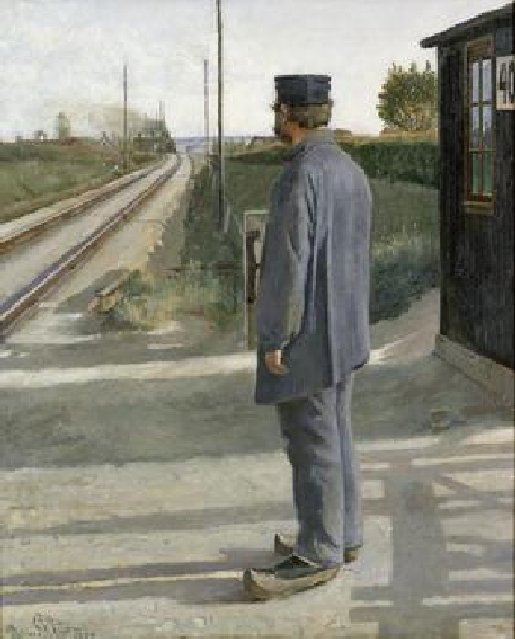

My favourite three paintings by Ring are ones which show his innate ability to portray everyday life. The first is his 1914 work entitled Waiting for the Train. Level Crossing by Roskilde Highway.

The second is his true to life work entitled Has it stopped Raining

And the third is his 1884 Social Realism painting entitled A Boy and Girl Eating Lunch in which we see two children sharing a bowl of broth which focuses on the plight of poor children who often struggled to get sufficient food.

Laurits Ring led a nomadic life during his single and married years. He frequently moved house preferring to live in small Zealand villages which probably reminded him of Ring, his birthplace. This life of wandering was interspersed by periods of calm and waiting.

Looking at Laurits Ring’s work reveals the extent to which the themes of travel and waiting infuse his art. His paintings record the historical changes that took place in the decades around the turn of the century. This was a period of great change with the coming of modern life and Ring tried to capture how it affected the less well-off.

In January 1914, Laurits and his family moved to a newly built house on Sankt Jørgensbjerg in Roskilde. Nine years after that move Laurits’ wife was taken seriously ill and on May 9th, 1923, three days before her 49th birthday, Sigrid Ring died of lung cancer. After his wife’s death Laurits, then sixty-nine, went to live with his twenty-one-year old son, Ole. In September 1933, Laurits Ring suffered a brain haemorrhage with slight paralysis of his left arm. He died on Sunday, September 10th, 1933, aged 79.

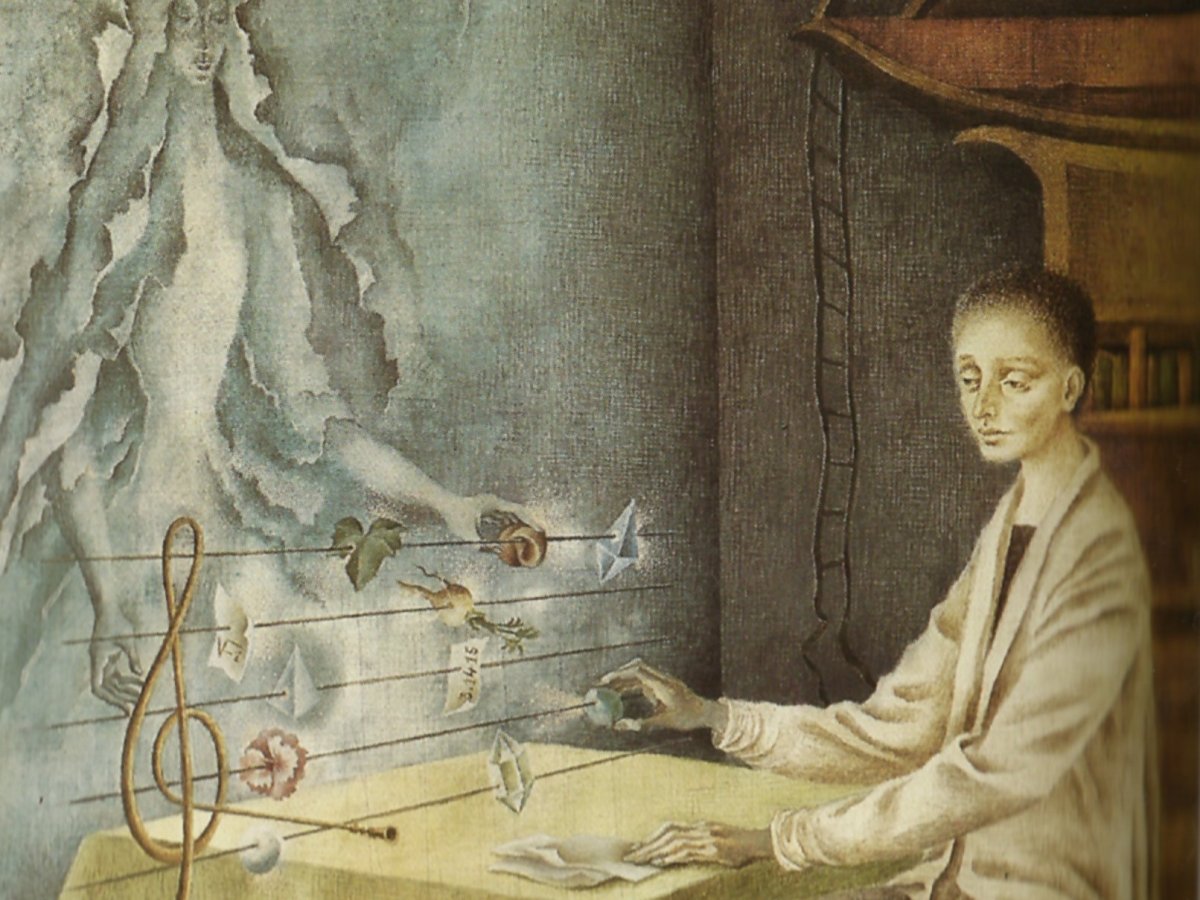

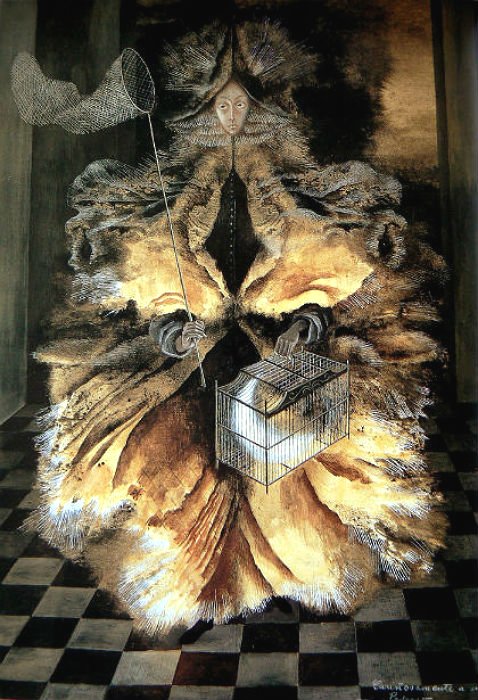

In 1958, Remedios Varo participated in the First Salon of Women’s Art at the Galerías Excelsior of Mexico, together with Leonora Carrington, Alice Rahon, Bridget Bate Tichenor and other contemporary women painters of her era. Remedios submitted two of her works, Harmony and Be Brief, and won the first prize of 3,000 pesos.

In 1958, Remedios Varo participated in the First Salon of Women’s Art at the Galerías Excelsior of Mexico, together with Leonora Carrington, Alice Rahon, Bridget Bate Tichenor and other contemporary women painters of her era. Remedios submitted two of her works, Harmony and Be Brief, and won the first prize of 3,000 pesos.

If you look closely at the chest cavity of the figure you will detect the circle of yin-yang, the Chinese symbol that similarly represents the balance of opposites. The face of the figure is one of calmness and serenity and suggests inner harmony and balance.

If you look closely at the chest cavity of the figure you will detect the circle of yin-yang, the Chinese symbol that similarly represents the balance of opposites. The face of the figure is one of calmness and serenity and suggests inner harmony and balance.

In 1963 Remedios suffered some health problems. She had complained of a shortage of breath when climbing stairs. She had a history of chronic gastric problems and was known to drink excessive amounts of coffee as well as being a heavy smoker. She was checked out for heart problems but was given a clean bill of health. The state of her mental health was open to doubt. Some of her friends said she was bubbly and full of life whist others said she had told them that she was depressed and did not know whether she could carry on with life. Walter Gruen, her husband, remembered the devastating afternoon of October 8th 1963, saying that he and Remedios had lunched with their friend Roger Cossio who had come to buy Varo’s painting, The Lovers. Gruen said his wife was happily explaining the details of the work to the buyer. With lunch over Cossio left and Gruen returned to his Sala Margolin shop across from their house to do some work. Shortly after, their Indian maid rushed into Gruen’s shop to tell him that Remedios was very ill. Gruen rushed home to find his wife complaining of chest pains. Gruen was unable to contact a doctor so left Remedios and went into the next room to consult some medical books. When he returned to his wife, he found that she had died.

In 1963 Remedios suffered some health problems. She had complained of a shortage of breath when climbing stairs. She had a history of chronic gastric problems and was known to drink excessive amounts of coffee as well as being a heavy smoker. She was checked out for heart problems but was given a clean bill of health. The state of her mental health was open to doubt. Some of her friends said she was bubbly and full of life whist others said she had told them that she was depressed and did not know whether she could carry on with life. Walter Gruen, her husband, remembered the devastating afternoon of October 8th 1963, saying that he and Remedios had lunched with their friend Roger Cossio who had come to buy Varo’s painting, The Lovers. Gruen said his wife was happily explaining the details of the work to the buyer. With lunch over Cossio left and Gruen returned to his Sala Margolin shop across from their house to do some work. Shortly after, their Indian maid rushed into Gruen’s shop to tell him that Remedios was very ill. Gruen rushed home to find his wife complaining of chest pains. Gruen was unable to contact a doctor so left Remedios and went into the next room to consult some medical books. When he returned to his wife, he found that she had died.

In her early days in Mexico, Remedios did few paintings and spent most of her time writing. She and Leonora Carrington would write fairy tales, collaborated on a play, invented Surrealistic potions and recipes, and influenced each other’s work. The two women, together with another of their friends, the photographer Kati Horna became known as “the three witches”

In her early days in Mexico, Remedios did few paintings and spent most of her time writing. She and Leonora Carrington would write fairy tales, collaborated on a play, invented Surrealistic potions and recipes, and influenced each other’s work. The two women, together with another of their friends, the photographer Kati Horna became known as “the three witches”