The Artist, the Poet, the Lover of Women.

The subject of this week’s blog is the nineteenth century Danish poet, dramatist and painter Holger Drachmann. Holger Henrik Herholdt Drachmann was born on October 9th, 1846 in Copenhagen. He was the son of Andreas Drachmann and his wife Vilhelmine. Holger was one of five children, having an older sister, Erna and three younger sisters, Mimi, Johanne and Harriet.

His father. Andreas, initially trained as a barber whilst studying for his medical exams. In 1831 he was an assistant to a surgeon in the Danish navy and eventually passed his exams to become a surgeon in 1836. He left the navy in 1845 and became a physician at Langgaard’s orthopaedic institute and in 1859 he founded the first institute of medical gymnastics in Copenhagen.

In March 1857, when Holger was ten years old, his mother Vilhelmine died. She was just thirty-six years old. Once he completed his schooling in 1865 he went to University where he remained for three years. He then transferred to the Academy of Fine Arts and studied under Carl Frederik Sørensen, a noted marine painter and soon Holger developed a love for that painting genre. Art was a great love of Holger but around this time he developed another love, a love of literature.

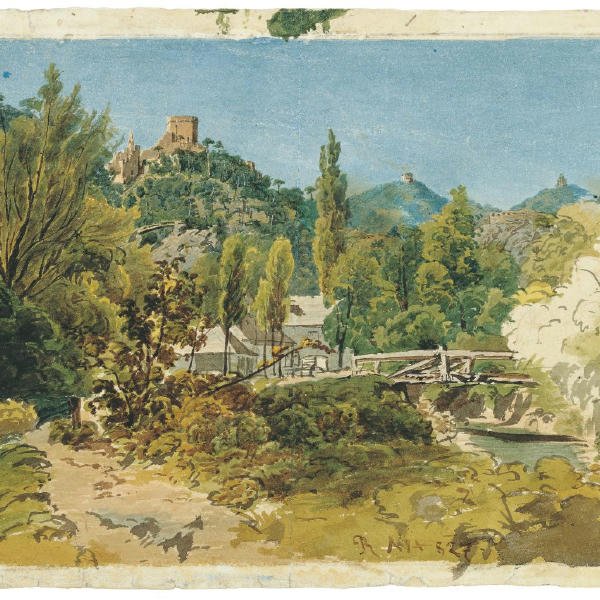

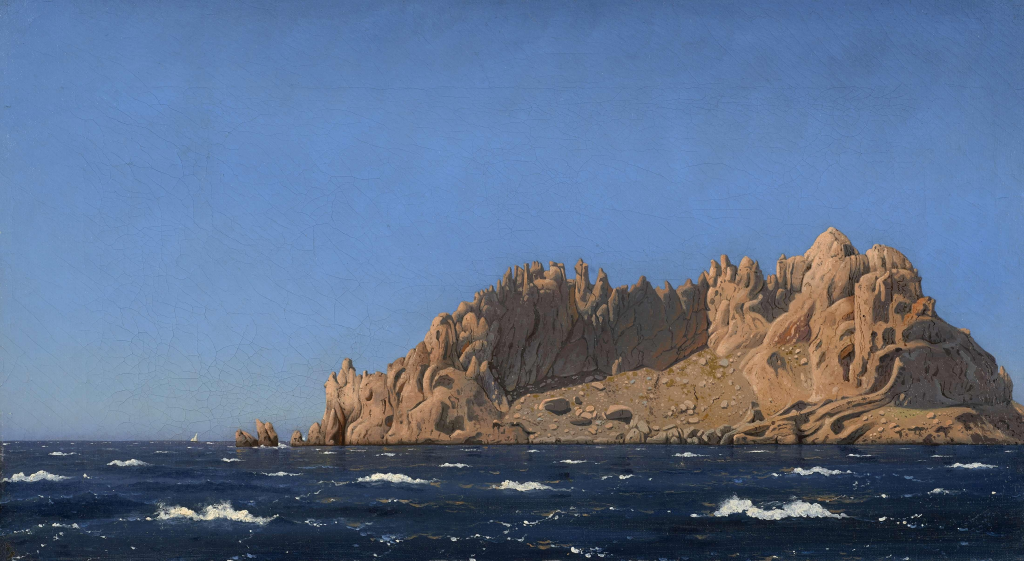

This painting above is thought to have been painted by Holger during his voyage around the Mediterranean in 1867.

The beauty and ferocity of the sea is captured in Drachmann’s painting entitled Rocky Coast. It depicts the unstoppable waves of the blue-green sea crashing violently against a towering rock formation in the foreground of the painting. To the left, we see heavy grey storm clouds. It is a depiction which is devoid of figures and one’s focus is simply concentrating on the violent force of nature. There is nothing noted as to the location of the scene but during his lifetime he visited many places, such as the Orkney Isles, and Norway, with their rocky coasts and archipelagos or it could have been locations in Newfoundland or Nova Scotia, places he visited during his long trip to North America.

To further his interest in marine painting, Holger went to stay on the island of Bornholm. This Danish island is located in the Baltic Sea, to the east of mainland Denmark, and south of Sweden. It was here he painted a number of seascapes. One of his Bornholm paintings depicted Vade Ovn, a notable rock or group of rocks attached to the underlying bedrock. It is a grotto, part of the area known as Helligdomsklipperne.

A wreck hut on Skagen’s beach by Holger Drachmann

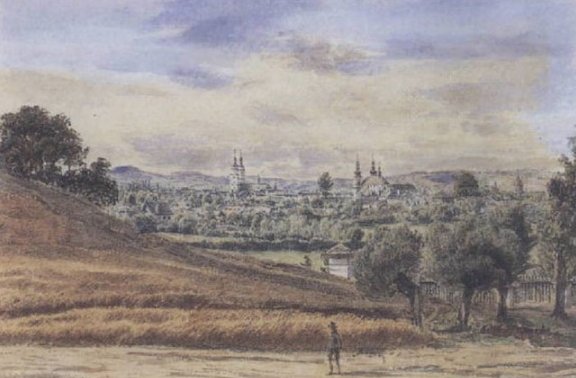

The Skagen artists’ colony is now as famous as the ones at Barbizon or Newlyn and Holger Drachmann was an important figure in the history of the Skagen artists’ colony, for it was he, who first arrived there in 1872 together with Norwegian Frits Thaulow, and he then persuaded many artists to go there with him during the following years. He fell in love with the area with its breath-taking nature and the simple life it afforded people.

Besides his love of painting and fame as an artist, Holger Drachmann had two other great loves. He had the love of literature and poetry and was a renowned poet. He was part of the Scandinavian Modern Breakthrough Movement which was a movement of naturalism and which debated the literature of Scandinavia, which replaced romanticism near the end of the 19th century.

Around 1870, Drachmann became motivated by the writings of the Danish critic and scholar Georg Brandes, who had greatly influenced Scandinavian and European literature. It was a time when art became secondary to literature in Drachmann’s life. He had travelled quite extensively around England, Scotland, France Spain and Italy and had started a habit of sending accounts of his travels to the Danish newspapers.

Drachmann made his debut in 1872 as a prose writer with the collection With Coal and ChalkIn and that same year he had a book of his poems entitled Digte (Poems) published. He also joined the group of young Radical writers who were also followers of Brandes. For Drachmann it was a time of contemplation and soul searching as to whether painting or writing would be his prime driving force. Drachmann established his position as the greatest poet of the Danish modern movement of his time with such collections as Dæmpede Melodier (1875; “Muted Melodies”), Sange ved Havet (“Songs by the Sea”) and Venezia (both 1877), and Ranker og Roser (1879; “Weeds and Roses”). The prose Derovre fra Grænsen (1877; “From Over the Border”) and the verse fairy tale Prinsessen og det Halve Kongerige (1878; “The Princess and Half the Kingdom”), demonstrated a patriotic and romantic trend that brought him into conflict with the Brandes group. Drachmann was one of the most popular Danish poets of modern time though much of his work is now forgotten. He unites modern rebellionist attitudes and a really romantic view of women and history.

Earlier I said that Drachmann had two great loves other than his art. He loved writing and poetry as I have just recorded but his other great love was women !

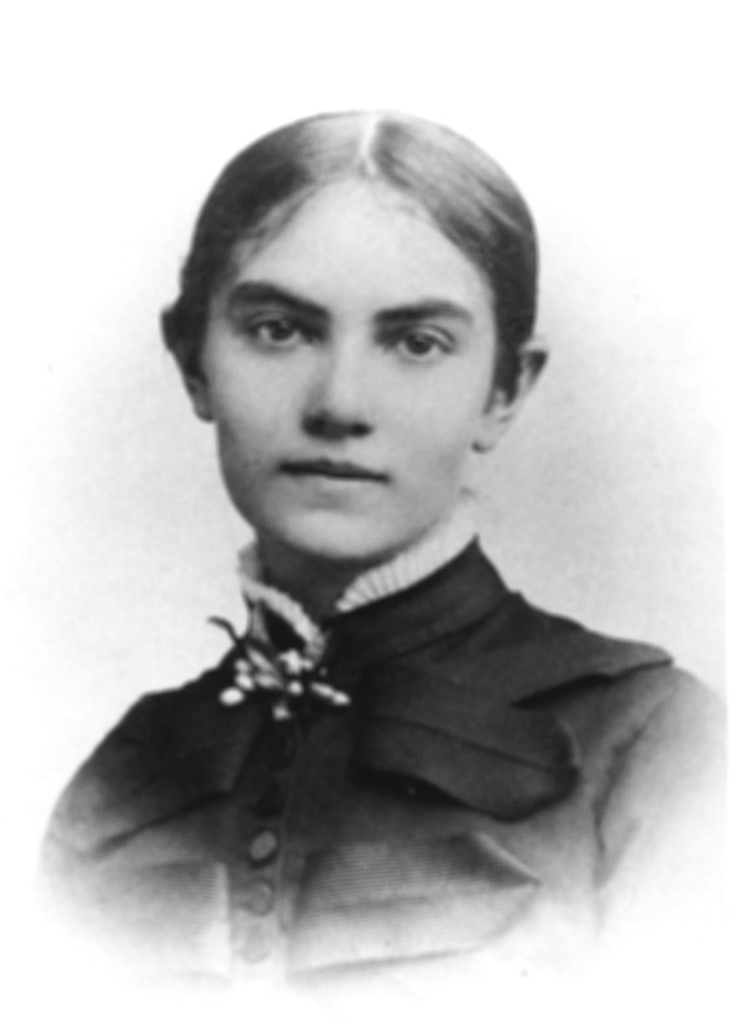

Whilst on the island of Bornholm in 1869, Holger Drachmann met his first wife Vilhelmine Charlotte Erichsen, She had been a good friend and muse for both Drachmann and another artist, Kristian Zahrtmann who was also living on Bornholm and who had painted her portrait when she was fourteen-years-old. Zahrtmann was besotted with the young girl who modelled for him. In a letter in 1868 to his friend and fellow artist August Jerndorff , he wrote:

“…I have had a young girl of mine of mine painting who interests me greatly. An adorable child – she is 16 years old – cannot be seen; After all, she is at an unfortunate age for most people, to which is added an extraordinary height and width, a short neck and stooped posture, but these are flaws that only all the more accentuate her beauty. A more regular face is unthinkable- – Her hair and eyes are almost black, her mouth bulging, and the pale yellow color, with its vexing and the utterly regular, narrow eyebrows, becomes so southern and melancholic dreamy that I can be so seized by it that the brush shakes in my hand. She herself does not know that she is beautiful, on the contrary, I think that she considers the yellow-laden color hideous, and at all she knows very little, both of knowledge and of what life is and gives…”

But three years later, in 1869, when she was seventeen, Vilhelmine fell in love with twenty-three-year-old Drachmann and they got engaged. Two years later, on November 3rd 1871 Holger and nineteen-year-old Vilhelmine married in Gentofte Sogn, København. To be able to marry Vilhelmine had to lie about her age, declaring that she was twenty-one. Holger was twenty-five years old and so did not need her parents’ permission for the marriage. On November 4th 1874 they had a daughter, Eva, but at the end of that year, they separated and finally divorced in 1878. It was a bad-tempered divorce and in a fit of rage Vilhelmine destroyed all correspondence and manuscripts from Holger that she possessed. Eva Drachmann wrote about her mother and father in her 1953 book Vilhelmine, my mother:

“…They divorced after 4 years of marriage. As the poet’s muse, Vilhelmine had entered into a cohabitation of whose seriousness and difficulties none of them had the slightest concept. Of the two, she was the largest child. She didn’t have time to grow up before it was all over. As an old woman, she reflected on how fateful the disaster came………. After all, in childhood and growing up, she had done nothing useful – nothing but dream…”

Eva Drachmann married for the first time in 1899 and the ceremony was held in a local manor house as the parish priest of the local Flade Church, refused to marry the couple in the parish church, citing Eve’s father’s godless lifestyle.

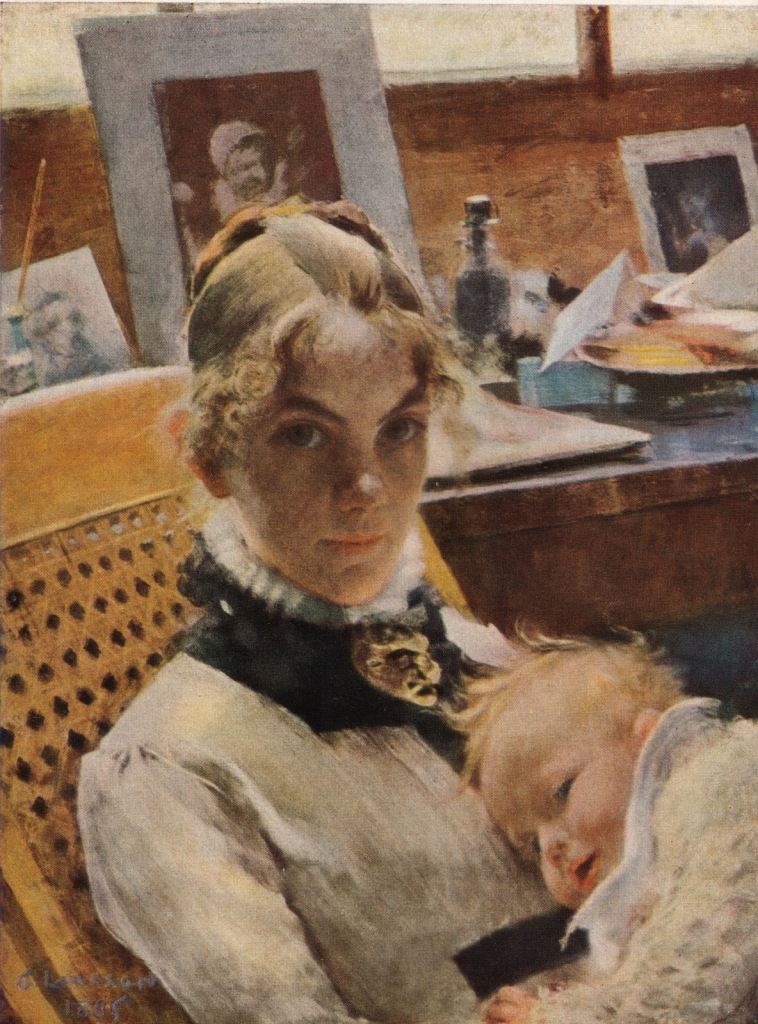

Polly Culmsee

Around 1866, three years before he met his first wife, Vilhelmine, Holger Drachmann had struck up a friendship with Valdemar Culmsee, the son of Frederick Culmsee, the owner of the Havreholm Paper Mill on the Danish island of Zealand. It was during a visit to their home in 1866 that he met Emmy Culmsee, Valdemar’s twelve-year-old sister and her older sister Polly who was sixteen. Polly had later married Charles Thalbitzer and had two children with him but around the time Holger Drachmann and his wife had separated in 1874 she had a relationship with Holger and had his child, Agnes Gerda. Polly eventually divorced her husband and she and Holger left Denmark for Sweden because of the social scandal they had created in Copenhagen. They intended to be married in Paris when Drachmann was legally divorced from his wife. Now living in the Swedish town of Lund, Polly fell ill and Drachmann took her to a local doctor, Alphons Theorin, and sought his help with the care of Polly. Bizarrely, Polly transferred her affection from Holger to the doctor who in turn fell passionately in love with his patient which created yet another scandal as the doctor abandoned his wife and their three children and ran off with Polly to the central Swedish town of Sveg, where he managed to arrange a position as a provincial doctor.

Emmy Culmsee

The bizarre story of Holger Drachmann love life does not end there. Polly’s younger sister Emmy had moved with her parents to Kristiania, where she stayed until she travelled to Hamburg in 1876 to study languages and it was in this German city that she once again met Holger. He told her he was devastated by a relationship break-up and she was very comforting. However he failed to impart to her that the relationship had been with her married sister, Polly. On finding out about the involvement of her sister she broke off with Holger and settled into a life as a German language teacher. However, in 1878 whilst on holiday in Hamburg, out of the blue, she received a call from Copenhagen from Holger Drachmann’s married sister Erna Juel-Hansen. She told Emmy that Holger had suffered a breakdown when Polly left him. Emmy went to Copenhagen and cared for Holger and nursed him back to full health. Emmy and Holger married and they adopted his and Polly’s daughter, Agnes Gerda. Emmy and Holger went on to have four more children of their own.

Amanda Jensine Nielsen (Edith)

Sadly in 1887 Holger, for whatever reason, began an affair with Amanda Jensine Nielsen a cabaret artist in Copenhagen, despite the fact that he was married and twice her age. He and Amanda became lovers and he would refer to her as Edith. He even mentioned her in his 1890 novel Forskrevet, a depiction of Denmark in 1880 and the then political dispute between Right and Left, as well as the cultural dispute between citizen and bohemian

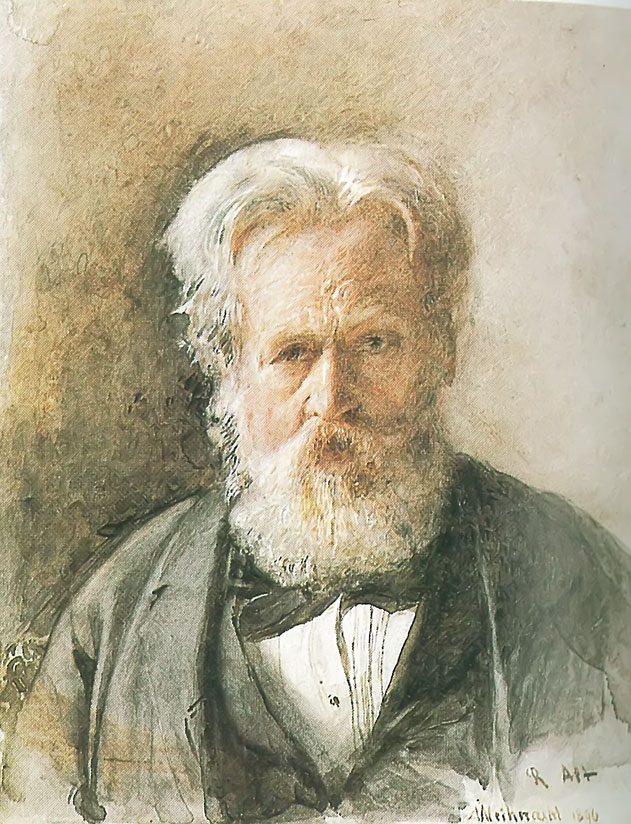

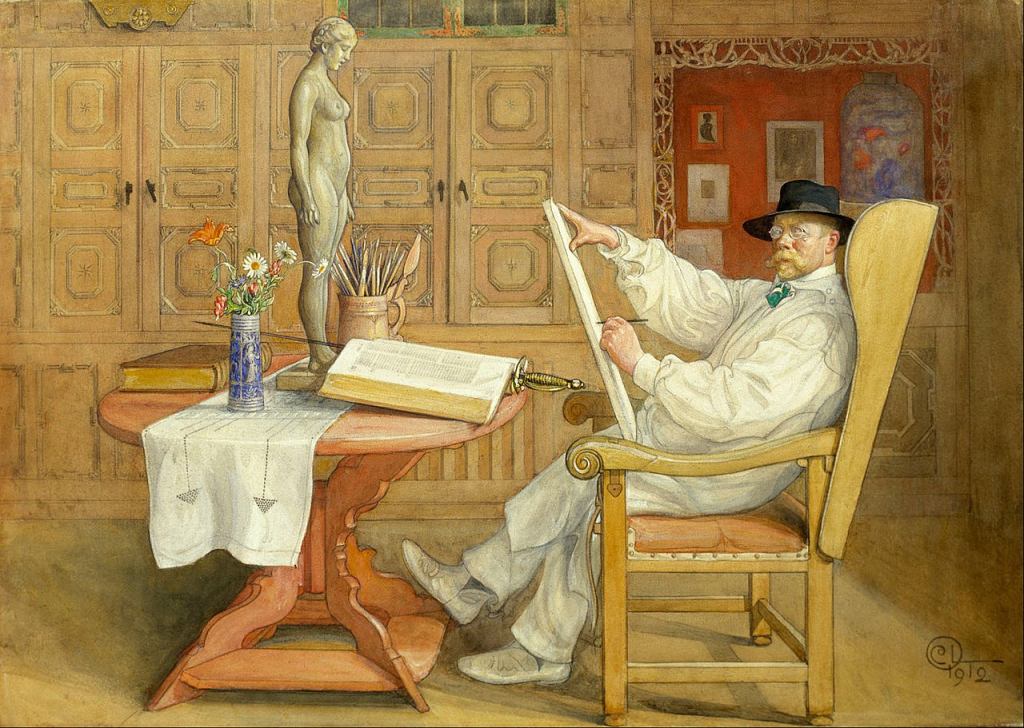

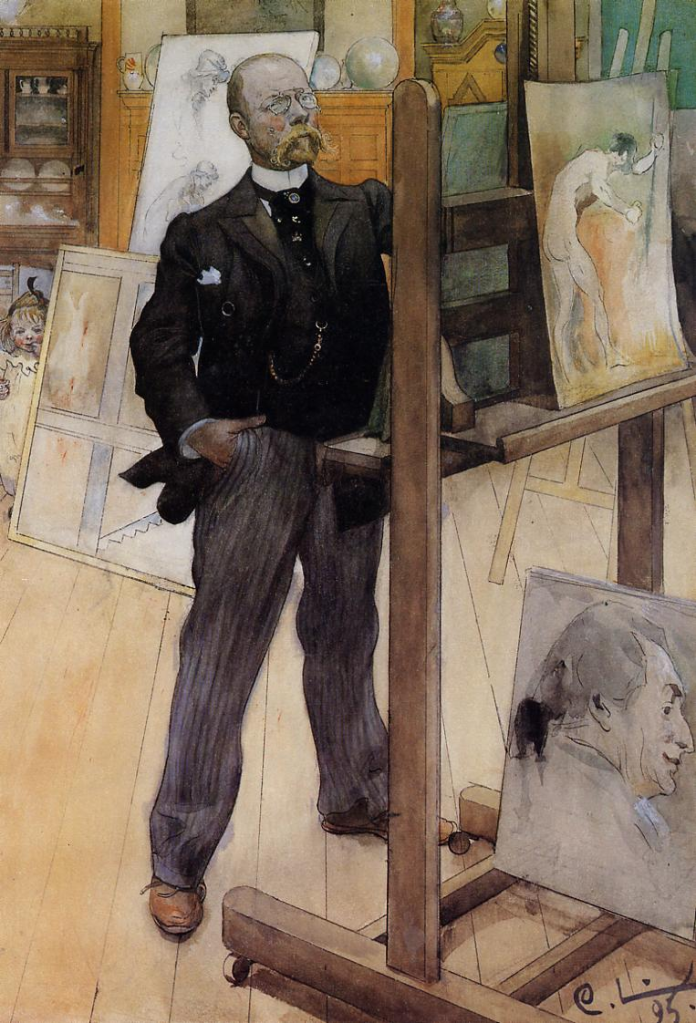

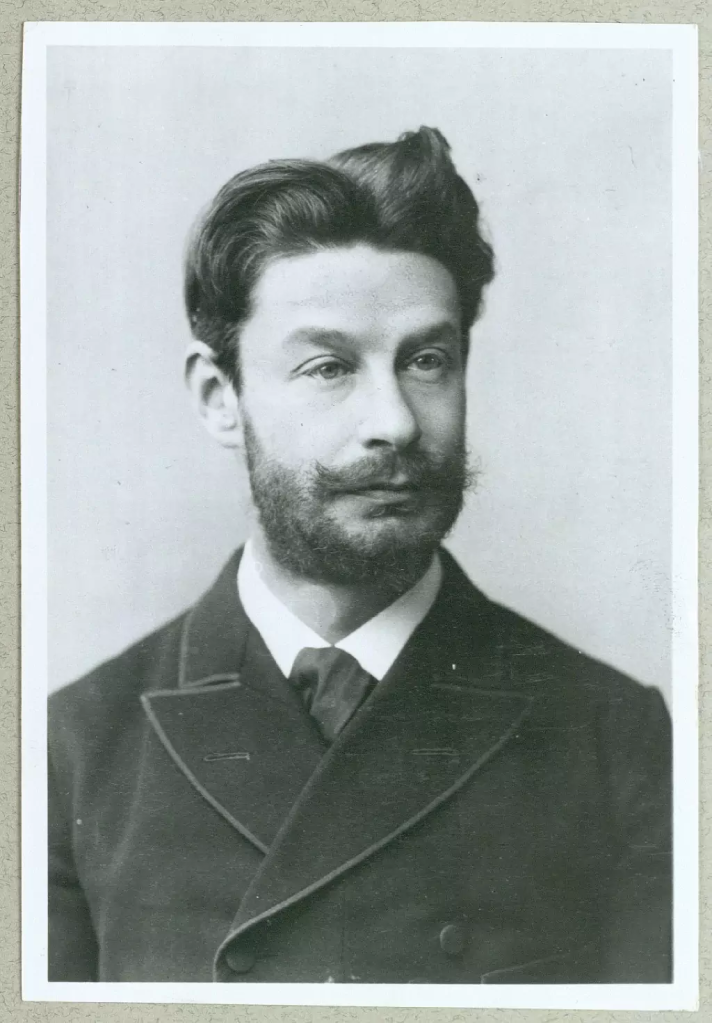

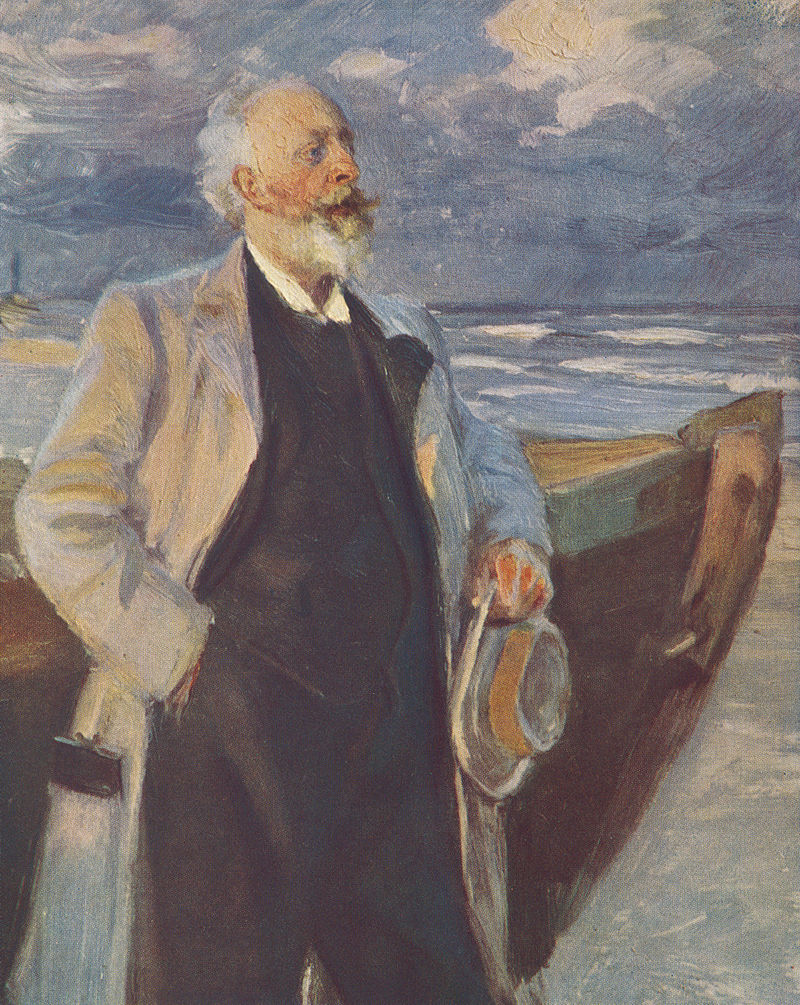

Holger Drachmann by Peder Severin Kroyer

Eventually Holger grew tired of his affair with Edith and moved on to another young actress. His many scandalous affairs with his “muses” were often the fuel of his inspiration. On his deathbed he said that his two biggest muses were Vilhelmine and Edith.

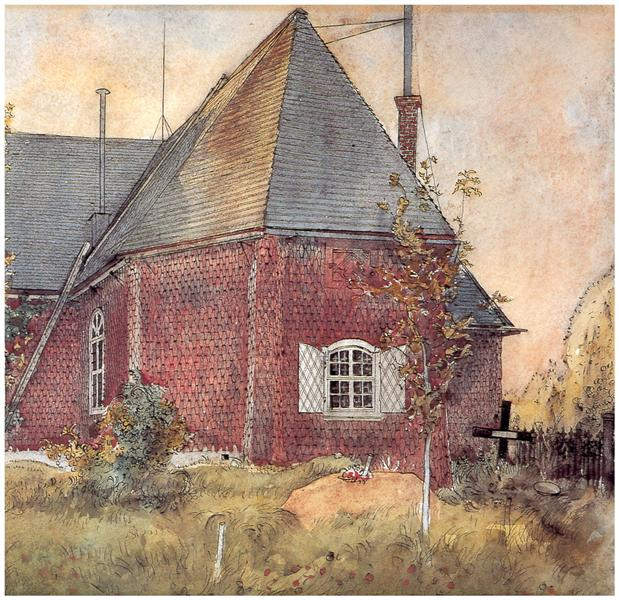

Drachmanns Hus in Skagen

Holger Drachmann died in Copenhagen on January 14th 1908, aged 61. He is buried in the sand dunes at Grenen, near Skagen and following his death his Skagen home, Drachmanns Hus, became a museum.