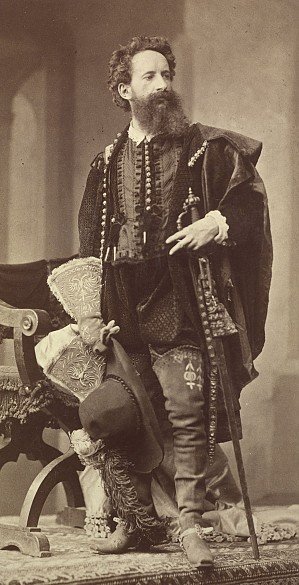

Photogrphed by Ludwig Angerer

The artist I am featuring in My Daily Art Display today is the Austrian academic history painter Hans Makart. He was an artist who was so loved by the high society of Vienna that he attained an almost cult-like status. He was born Johann Evangelist Ferdinand Apolinaris Makart in Salzburg in May 1840. His mother was Mary Catherine Rüssemayr and his father was John Makart, who was the chamberlain at the Mirabell Palace in Salzburg. He must have shown some artistic talent as a youngster for he enrolled at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts in 1858. His tutor was the Austrian painter of genre pieces and landscapes, Johann Fischbach. However, his tenure at this famous art establishment was short lived as his tutors found that he lacked the talent to become an academic painter. Hans Makart was not to be put off by the comments of his former tutors as he still retained a great self-belief in his artistic ability. In 1860 Makart moved from Vienna to Munich and in 1861 enrolled at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste München, also known as the Munich Academy and, for four years, studied under the tutelage of the German painter and Munich Academician, Karl von Piloty. During those four years he also found time to visit London, Paris and Rome.

His artistic “break” came in 1868 but the lead up to his opportunity began ten years earlier. The inner city of Vienna in 1857 was ringed by its 13th century city walls. However in that year the emperor, Franz Josef, decreed that the walls should be demolished and in their place a wide thoroughfare was to be built, which would circle the inner city. This large-scale building project was financed, in part, by the sale to private individuals, of land alongside the proposed boulevard, which had not been set aside for public buildings or parks. The work started in 1858 and was completed seven years later. It became known as the Ringstraße and soon buildings, both private and public, were erected along the tree-lined boulevard. People loved their new boulevard and would take the opportunity to stroll along the Ringstraße. This love of promenading by the citizens of Vienna was captured in Theodore Zasche’s work entitled The Ringstrasse, Vienna.

One of the first public buildings erected along the Ringstraße was the Vienna Künstlerhaus which was completed and opened in September 1868 and became home to the Austrian Artists’ Society. To mark its opening it held an art exhibition and Hans Markt was invited to submit some of his work. One of the paintings he sent was a very large triptych entitled Moderne Amoretten (Modern Cupids). It was such a large work that he even sent written instructions and drawings as how it was to be hung to achieve the best visual result. All three paintings were bought by Count Johann Palffy who later commissioned more work from Makart, including a portrait of his wife. A few months after the end of the exhibition Emperor Franz Joseph, who had already acquired some of Makart’s works, invited him to return to Vienna and in return for doing so, he was provided with a large studio, for his art work, which had once been a foundry.

Makart filled the place with sculpture, ornate furniture, musical instruments and flowers, all of which he used as a backdrop to his historical works and for his staged elaborate and opulent interiors which he incorporated as backgrounds for some of his portraiture. Before long the former foundry was not just a simple, if large, artist’s studio, but a Salon and it was here he would invite his friends, models and patrons. He entertained everybody notwithstanding whether they were nobility or bourgeoisie. The social class of his guests mattered little to him, all he wanted from them was their adoration of him as an artist. It was simply his showroom for marketing his paintings. The visitors were merely his admiring audience and soon he became the talk of the Viennese high society. He had become a cult hero and he loved every minute of it. He had become the leading artistic figure of Viennese society.

Makart did not shy away from controversy. He saw nothing controversial in his art work and in fact he realised that controversy could work in his favour. Alexander Klee, a curator at Vienna’s Belvedere museum commented on this aspect of Makart’s art, saying:

“…Part of the scandal came from erotic features in his paintings. Adults kissing, loose-fitting clothing, an uncovered ankle, monks receiving sexual favours, gold backgrounds inspired by church paintings with nudes in the forefront, depictions of sex and crime – these were all scandalous and sometimes almost blasphemous compositions…”

One such painting which caused ructions was one Makart completed in 1878 entitled The Entry of Charles V into Antwerp. In the work we see Charles V, the ruler of the Holy Roman Empire, depicted arriving in Antwerp in 1525. Makart has depicted the triumphal procession surrounded by beautiful scantily-clad virgins. Art critics of the time questioned why such nudity should appear in a modern historical scene and suggested that their inclusion was simply a tawdry way Makart had used to be noticed. In the United States, the painting fell afoul of the Comstock Law, a law named after Anthony Comstock, the United States Postal Inspector and politician dedicated to the strict ideas of Victorian morality which made illegal the delivery or transportation of “obscene, lewd, or lascivious” material . As we know, there is no such thing as bad publicity and despite prints of the painting being banned in America, the Americans were desperate to see the work and make their own judgement and of course the painting, in a round-about way, secured Makart’s fame in that country.

However maybe the critics were overly harsh about Makart’s inclusion of semi naked women in the historical painting as Albrecht Dürer in his book, Journal of a Voyage to the Netherlands wrote:

“…I gave a sou for a little book describing the entry into Antwerp where the king received a costly triumph. The city gates were ornamented in the most costly manner; there was music and great rejoicing, and beautiful maidens whose like I have seldom seen…”

And in 1526 Dürer wrote to his friend with regards the scene, writing:

“…I looked at these young women very attentively and closely, and without shame, because I am a painter…”

One presumes Makart was aware of Dürer’s comments as he included him in the crowd scene in his work!

Another historical painting Makart completed in 1875 was sold at auction this year for 757,300 Euros. It was his work entitled Death of Cleopatra. The painting depicts the dramatic moment immediately after the snake has plunged its poisonous fangs into Cleopatra’s breast. The portrayal of the dying queen derives its intensity from the contrast between the depiction of Cleopatra’s luxurious silk garments along with her glittering gold jewellery that adorn her body and the pale opaqueness of her skin. We see the blue tinge on her right breast at the point where the asp has struck. The sitter for this painting was a friend of Makart, Charlotte Wolter, a Viennese actress. Gabriel Frodl, who was once director of the Belvedere in Vienna, describes how Makart set the scene:

“…In this manner, the painter conveys an erotic-lascivious mood, further emphasised by the palpable vulnerability of the body, doomed to die among the now insignificant luxury of its surroundings…”

Makart’s artistic work had now branched out in many directions. He not only created works of art on canvas but also designed costumes and furniture and conceived elegant interior designs for upper-class residences and his work became known as Makartstil (Makart-style). In 1879, just before his fortieth birthday, he was commissioned to organise a pageant and parade as part of the Silver Wedding Anniversary celebrations of the marriage of Emperor Franz Josef and his wife, Elizabeth of Bavaria.

It was a great success and Makart took this as an opportunity of self-aggrandisement for besides designing the costumes for the people on the floats, cars and carriages and the scenic settings for the various floats he designed a float specifically for artists, which would head the parade and this would be headed by Makart himself on a white horse. It is no wonder that this parade later became known as the Makart-parade. The Makart-styled parade was such a success with the Viennese people been given the opportunity to dress up in beautiful historical costumes and be “transported” back to bygone times. Such was the triumph of this parade and pageant that annual parades followed.

One could not end a blog about Makart and his paintings if one did not delve into his portraiture. Many men sat for their portraits but it is Makart’s sensual and seductive portraits of upper-class females which were his best. One such painting was his 1883 Portrait of Anna von Waldberg which he completed a year before her death. In the painting we see her wearing a black bustle-era evening dress with its low-cut neckline. The design was less conservative but incorporates a black bow as a modesty piece hiding the lady’s cleavage.

The final work of Makart which I am featuring is his famous; some would say his infamous, five-panel oil painting entitled Die Füunf Sinne (The Five Senses) which he completed in around 1879. It is a study in the nude, depicting five different views of his ideal female form under the guise of the five senses: the senses of smelling, seeing, hearing, feeling and tasting. Each of the five senses is represented by the action of the female nude.

Hans Makart died in October 1884, aged 44. He was buried in an honorary grave in Vienna’s Central Cemetery. The Austrian postal service has issued a number of stamps honouring his memory, the most recent being in 1990 to commemorate the 150th anniversary of his birth.