My featured artist today is the nineteenth century French painter Eugène Boudin. He was one of the earliest en plein air painters and is credited with introducing plein air painting to Monet. He was a marine painter and his depictions focused on seascapes and the Normandy shorelines.

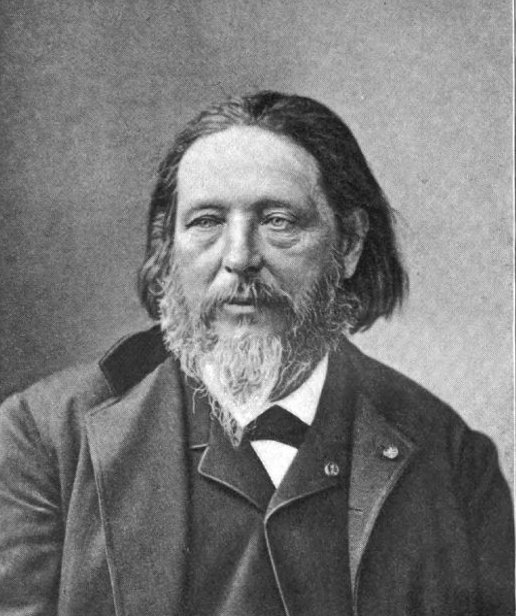

Portrait of the Artist’s Father by Eugène Boudin (1850)

Eugène Louis Boudin was born in the coastal town of Trouville in Normandy on July 12th 1824. Leonard-Sebastien Boudin, Boudin’s father, was a harbour pilot, and at the age of ten, young Boudin worked as a cabin boy on a steamboat that sailed across the Seine estuary between Le Havre and Honfleur and during those days on the water the young boy must have witnessed the constant fluctuations of the colours of the sea and sky which were aspects so important to plein air artists. Boudin’s father gave up his seagoing life when Eugène was about twelve years of age. In 1835, Eugène moved with his family to Le Havre where his father established himself as stationer and frame-maker. Eugène began work the following year as an assistant in the shop before opening his own small framing shop which he co-owned. It was whilst running this shop that he first met artists who were working in the area and used his shop to exhibit their paintings. The most well-known of these were the landscape painter, Constant Troyon, Jean-Francois Millet, the portraiture artist, Jean-Baptiste Isabey and the history painter, Thomas Couture. Eugène would receive encouragement from these painters to abandon the world of commerce and take up painting. In 1846, aged twenty-two, Eugène Boudin took their advice and gave up the stationery shop and began to paint full time. He had sold his share of the business to buy himself out of military service and in 1847, he travelled to Paris and spent time travelling through the Flanders region. Boudin was profoundly influenced by the Dutch 17th-century Masters and when he met the Dutch painter Johan Jongkind, who had already made his mark in French artistic circles, Boudin was advised by his new friend to paint en plein air. Three years later, in 1850 he won a scholarship that allowed him to move to Paris. However, he never forgot his roots and would return to Normandy to paint and later take many painting trips to Brittany.

The Road from Trouville to Honfleur by Eugène Boudin (c.1852)

During that early period, Eugène painted rural landscapes, peasants, and still life works, but soon his love of the sea and the seaside progressively attracted his attention, and in 1862, he began to paint the crowds of fashionable tourists who had descended on the Normandy beaches. Seaside resorts began to appear on the French Channel coast and in what was to become Belgium and the Netherlands in the late eighteenth century. By the early nineteenth century the commercial sea-bathing habit was making an impact on Normandy.

Fishermen by the Water by Eugène Boudin (1855)

Up until that time artists’ coastal scenes were rarely populated, and if they did include figures they were likely to be local fishermen. Boudin’s coastal scene paintings were adventurously modern in nature depicting smartly dressed holidaymakers engaging in leisure activities.

Elegant Women on the Beach by Eugène Boudin (1863)

His modus operandi was to sketch en plein air during the summer months and finish off the paintings in his studio during the winter months. Boudin still respected the established tradition of outdoor painting. His plein air sketches were merely studies rather than finished works and they had to be finalized in his studio utilizing the many sketches he had made as well as the meticulous notes he had recorded about atmospheric conditions and the time of day when the sketches had been made. It was a painstaking operation as he once wrote in a letter to one of his students:

“… An impression is gained in an instant, but then it has to be condensed following the rules of art or rather your own feeling, and that is the most difficult thing – to finish a painting without spoiling anything…”

However, Boudin changed his methodology realising that there was an innate wrongness with his system of completing works indoors and so he would, from start to finish, complete his works en plein air. This inherent immediacy of work painted outdoors allowed him to be aware of changing weather and light conditions.

The Beach at Villerville by Eugène Boudin (1864)

Claude Monet was born in Paris on November 14th 1840 and at the age of five moved with his family out of the French capital and went to live in Le Havre. Monet was fourteen years younger than Boudin but it is said that around 1856, sixteen-year-old Monet met fellow artist Eugène Boudin, who then became his mentor and taught him to use oil paints. Boudin who befriended him also taught Monet the technique for outdoor painting. This was to have a great influence on the young artist. Up to the early meetings with Boudin, Monet had concentrated on his teenage caricatures but was persuaded by Boudin to focus all his time on landscape painting. Monet recalled the time:

“…it was as if a veil had been torn from my eyes. I had understood, had grasped what painting could be. Boudin’s absorption of his work, and his independence, were enough to decide the entire future and development of my painting…”

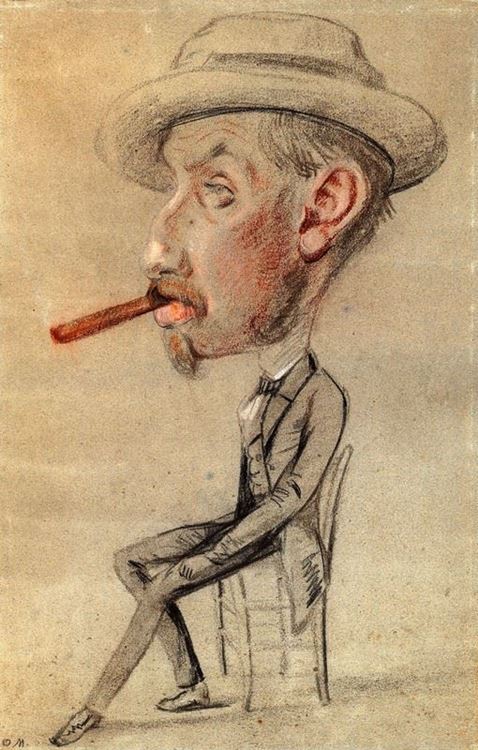

Caricature of a Man with a Big Cigar by Monet (1855-1856)

Boudin helped Monet to love the bright hues and the play of light on water. Monet remembered Boudin’s words of encouragement and later paid tribute to Boudin’s early influence:

“…Boudin without hesitation, came up to me, complimented me in his gentle voice and said ‘I always look at your sketches with pleasure, they are amusing, clever, bright. You are gifted; one can see that at a glance. But I hope you are not going to stop there. It is all very well for a beginning, yet soon you will have had enough of caricaturing. Study, learn to see and paint, draw, make landscapes. The sea and the sky, the animals, the people and the trees are so beautiful, just as nature had made them, with their character, their genuineness, in the light, in the air, just as they are’…”

Laundresses by a Stream by Eugène Boudin

This would later become evident in Monet’s Impressionist paintings. Boudin offered Monet the chance to help him in his framing shop but the young man declined but later that summer he acquiesced. The two remained lifelong friends and it was probably through Monet that Boudin was asked to participate in the First Impressionist Exhibition in 1874.

In 1859 Boudin met Gustave Courbet who introduced him to the poet and art critic, Charles Baudelaire, who was the first critic to draw Boudin’s talents to public attention when he made his debut at the 1859 Paris Salon.

Deauville Harbour by Eugène Boudin

Boudin was to later join Monet and his young friends in the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874, but he never considered himself a revolutionary trend-setter unlike some of the other artists. So now Boudin’s work featured at both the Imressionist’s First Exhibition as well as at the Paris Salon that year. In a way Boudin had created a vital connection between the past and future trends of French art, and by so doing won the admiration of his contemporaries. Boudin could have become a regular member of the Impressionists but chose not to.

Boudin had mental issues in the form of bouts of melancholia and he always seemed to doubt his own ability. He was introverted and never felt the need to bolster his reputation which may have been enhanced if he had decided to live in the French capital and regularly mix within the Paris art circle. Boudin preferred to remain living in Normandy.

In a letter, from Paris, dated June 14th 1869, to family-friend Ferdinand Martin Boudin tells of his desire to return to Normandy:

“…I dare not think of the sun-drenched beaches and the stormy skies, and of the joy of painting them in the sea breezes…”

The paintings that Boudin made of the coast were consistent with the ideals of the depiction of light which became popular with the Impressionist movement and so we must realise that Boudin continued to be an influence with the group.

Beach at Trouville by Eugène Boudin

Boudin was a master when it came to depicting skies. Fellow artists, like Corot, praised that aspect of Boudin’s paintings and nicknamed him King of the Skies. In 1859 the poet Charles Baudelaire rhapsodically described the skies in Boudin’s paintings, shown at the Salon, ‘prodigious spells of air and water’.

………..to be continued.

Our hopes were soon dashed as we set about reading The History of Mr Polly which I remembered to be both turgid and depressing but there again I have to admit I was never an avid reader. The Shakespearean play was the Merchant of Venice which proved a lucky choice and one which I especially enjoyed when we looked at it in depth. Then came the poem. Poetry was anathema to sixteen year old boys and “boys don’t do poetry” was our class mantra and one needs to remember that our school was an all-boys one. Add to that the feeling of gloom about embarking on reading and learning lines of the poem for furthermore this chosen poem, which we had to study was not a short one with just a few stanzas but an extremely long one. It was The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, which was the longest major poem by the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and one he completed and had published in 1798. Unbelievably it proved to be my favourite part of the English Literature exam syllabus.

Our hopes were soon dashed as we set about reading The History of Mr Polly which I remembered to be both turgid and depressing but there again I have to admit I was never an avid reader. The Shakespearean play was the Merchant of Venice which proved a lucky choice and one which I especially enjoyed when we looked at it in depth. Then came the poem. Poetry was anathema to sixteen year old boys and “boys don’t do poetry” was our class mantra and one needs to remember that our school was an all-boys one. Add to that the feeling of gloom about embarking on reading and learning lines of the poem for furthermore this chosen poem, which we had to study was not a short one with just a few stanzas but an extremely long one. It was The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, which was the longest major poem by the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and one he completed and had published in 1798. Unbelievably it proved to be my favourite part of the English Literature exam syllabus.

And so to the Samuel Coleridge Taylor poem, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. Doré was excited about illustrating the poem, so much so he had completed the designs for the illustrations before a deal had been struck with the publisher. The wooden blocks he used for the illustrations were very large and cost Doré a lot of money and unlike previous engravings he took control of the supervision of them. Doré believed that this was his greatest work but unfortunately for him, its sales recouped him only slowly for his large initial outlay. It was first published in England and soon editions appeared in France, Germany and America.

And so to the Samuel Coleridge Taylor poem, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. Doré was excited about illustrating the poem, so much so he had completed the designs for the illustrations before a deal had been struck with the publisher. The wooden blocks he used for the illustrations were very large and cost Doré a lot of money and unlike previous engravings he took control of the supervision of them. Doré believed that this was his greatest work but unfortunately for him, its sales recouped him only slowly for his large initial outlay. It was first published in England and soon editions appeared in France, Germany and America. Samuel Coleridge Taylor did not set his poem in any one period but as an illustrator, Doré had to be more precise and he chose a medieval setting for the wedding feast at the start of the poem.

Samuel Coleridge Taylor did not set his poem in any one period but as an illustrator, Doré had to be more precise and he chose a medieval setting for the wedding feast at the start of the poem. It is an ancient Mariner,

It is an ancient Mariner, With sloping masts and dipping prow,

With sloping masts and dipping prow, And through the drifts the snowy clifts

And through the drifts the snowy clifts At length did cross an Albatross:

At length did cross an Albatross: However for some unknown reason the Ancient Mariner shot the albatross with his crossbow.

However for some unknown reason the Ancient Mariner shot the albatross with his crossbow. Water, water, every where,

Water, water, every where, There passed a weary time. Each throat

There passed a weary time. Each throat The ghostly hulk approaches their ship and on board are two figures, a skeletal Death and a deathly pale female, Night-mare Life-in-Death and the two are playing dice for the souls of the crew members. Death wins the lives of all the crew members, all except for the Ancient Mariner, whose life is won by Night-mare Life-in-Death. It is the name of this character that allows us to know the fate of the Ancient Mariner – a fate worse than death, a living death, was to be his punishment for killing the albatross.

The ghostly hulk approaches their ship and on board are two figures, a skeletal Death and a deathly pale female, Night-mare Life-in-Death and the two are playing dice for the souls of the crew members. Death wins the lives of all the crew members, all except for the Ancient Mariner, whose life is won by Night-mare Life-in-Death. It is the name of this character that allows us to know the fate of the Ancient Mariner – a fate worse than death, a living death, was to be his punishment for killing the albatross. The Ancient Mariner is the sole survivor of the ill-fated crew. The bodies of the dead crew members lay around the deck with their eyes staring at the Ancient Mariner. The Ancient Mariner recounts how he felt, how he wanted to die but was not allowed that luxury.

The Ancient Mariner is the sole survivor of the ill-fated crew. The bodies of the dead crew members lay around the deck with their eyes staring at the Ancient Mariner. The Ancient Mariner recounts how he felt, how he wanted to die but was not allowed that luxury.

![Nouvelles théories sur l'art moderne [et] sur l'art sacré, 1914-1921 by Maurice Denis](https://mydailyartdisplay.files.wordpress.com/2016/04/nouvelles-thc3a9ories-sur-lart-moderne-et-sur-lart-sacrc3a9-1914-1921-by-maurice-denis.jpg?w=208)