Anton Pieck

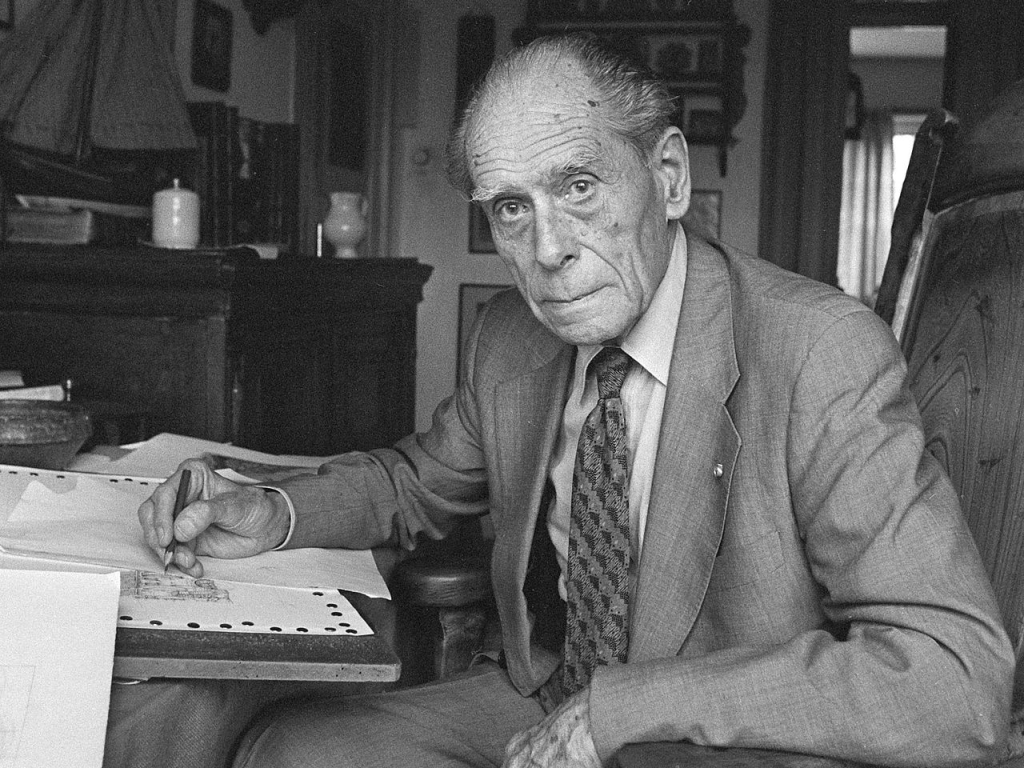

When one thinks of artists, one looks to the greats such as Veronese or Goya or Turner and some are maybe somewhat “sniffy” when graphic artists and illustrators are lumped together with such luminaries. My artist today was reviled by serious art lovers for his artwork being petty kitsch. Still, friend and foe had to admit that he was an accomplished draftsman with a highly unique, instantly recognizable and barely imitated style. However, whether you love or hate his work my featured artist today is one of the great illustrators of his time and whose works have brought unbridled happiness to many. For those who have never seen any of his works, let me introduce you to the Dutch graphic artist Anton Pieck.

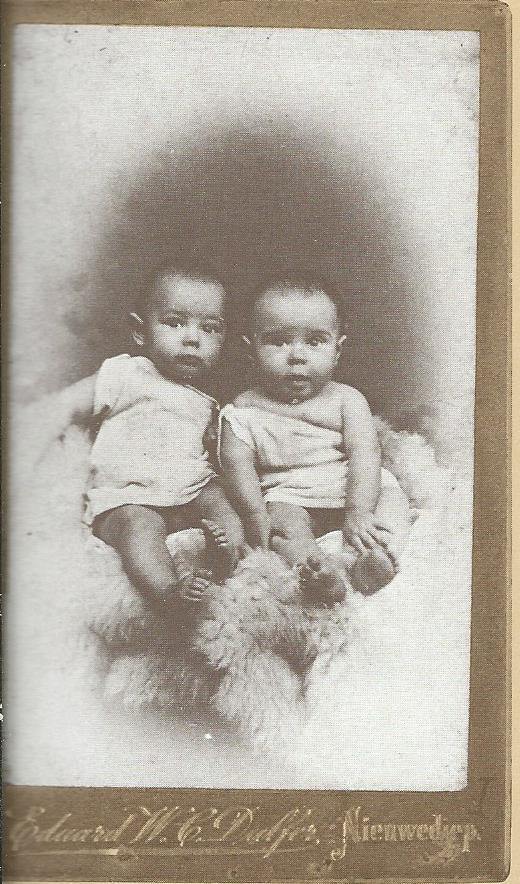

Anton Pieck aged 1 year-old, on the left, next to his twin brother Henri Pieck

Anton Franciscus Pieck and his twin brother, Henri, were born in the Dutch town of Den Helder on April 19th, 1895. He was the son of Henri Christiaan Pieck, who was a machinist in the Royal Dutch Navy, so he was often away from home for lengths of time. His wife was Stofffelina Petronella Neijts who gave birth to their first child, Coenraad, in 1891 but who died when he was just one year old. Anton’s twin brother Henri Christiaan became a Dutch architect, painter and graphic artist but who would lead a different, more exciting and dangerous life than his brother Anton. As an adult Henri became active within the Dutch Communist Party, and was recruited as a spy for Soviet Russia. Henri’s artistic interests differed from those of Anton as his main love was modern art, whereas Anton loved old-fashioned illustrations and paintings . When the twins were six years old, they took drawing lessons from J. B. Mulders, who ran after-school art classes at their school. He recognized the talent of the twins and taught them the basics of perspective and proportion, and these lessons quickly bore fruit. When he was ten, Anton won a prize at an exhibition for his still life watercolour depicting a brown pot on an old stove, and in recognition, among other things, he received five tubes of watercolour paints. More awards followed during his teenage years.

River Spaarne and the Bakenesser Tower by Anton Pieck

In 1906, after Anton’s father retired, the family moved to live in The Hague. Anton and his brother, after finishing secondary school, enrolled on a drawing course in the evenings at the Royal Academy of Art. They later received training at the drawing institute Bik and Vaandrager. When the brothers were aged fourteen, they obtained the first stage of their teaching certificate and 3 years later they completed their teaching certificates and were able to call themselves drawing teachers. Anton went to teach at his old school, Bik and Vaandrager. Henri Pieck was considered the better artist of the twins and is allowed to go to the Academy of Fine Arts in Amsterdam. This was a personal blow to Anton who never came to terms with the fact that his twin brother was looked upon as the more skillful artist. One could almost say that Henri was looked upon as an artist whereas Anton was looked upon as a drawing teacher!

During the First World War the Netherlands remained neutral, but still many young Dutchmen were mobilized so as to be on standby in case their country became embroiled in the fighting. Anton Pieck was one of those men and became a sergeant, however he spent most of his spare time sketching for his fellow recruits. A somewhat damning psychological army report on him in 1915 described Pieck as:

“…someone who looks more at the past than the future and will therefore never amount to anything…”

Not considered as “fighting material” and unlikely to be used for military duties, Pieck was sent back to The Hague, where he gave drawing lessons to other soldiers. This was pure heaven for Anton as for four evenings a week he would oversee two-hour sketching lessons. Pieck was then able to spend all his time doing what he loved best.

A boat on the River Amstel near Ouderkerk with the house “Wester Amstel” by Anton Pieck

When Anton graduated from the Bik en Vaandrager Institute, they offered him the position as an art teacher which he accepted and held the position until 1920. He then applied and was accepted as an art teacher at the newly established Kennemer Lyceum, a high school in the Haarlem suburb of Overeen. He would continue to work there until his retirement in 1960 at the age of 65. Throughout those years teaching students, he always made time for his own work.

Hofje van Loo with communal water pump by Anton Piecke. The Hofje (Courtyard) van Loo is a hofje on the Barrevoetstraat 7 in Haarlem

Teaching art was not his great love and he was never quite satisfied with his job and he couldn’t wait for his daily teaching duties to end so that he could dash home and continue drawing and painting. However, being employed as a teacher gave him financial stability and this in turn gave him the comfort of only choosing commissions which pleased him, rather than being forced to work on work he disliked. Whilst employed at the school as a teacher, Anton would also illustrate diplomas, bulletins, ex-libris bookplates, birth cards and other administrative documents for his school.

The River Spaarne with the Waag building designed by Lieven de Key at the end of the 16th century by Anton Pieck

In the 1920’s Anton Pieck published his first drawings. It was also around this time that Anton forged a close friendship with the Flemish novelist Felix Timmermans and it is said that Timmermans’ jovial attitude rubbed off on Pieck whom he advised to “lighten up” and be more spontaneous and follow his own spirit.

A recent edition of Felix Timmerman’s book.

For the 10th edition of Timmerman’s very successful book, Pallieter, published in 1921, Timmermans asked Pieck to provide the illustrations to go side-by-side with the text. Through correspondence, Timmermans indicated what he wanted to see on the illustrations. The book was described as an ‘ode to life’ written after a moral and physical crisis. Pallieter was warmly received as an antidote to the misery of World War I in occupied Belgium. For Pieck, this was just a start of his book illustration journey as he went on to illustrate about 350 books.

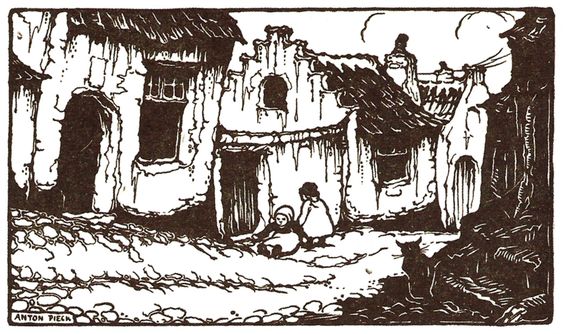

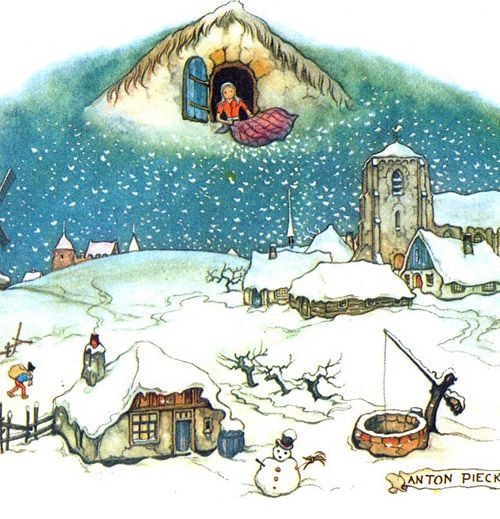

In 1921 Pieck illustrated Felix Timmermans’ book Pallieter by the Flemish author Felix Timmermans. As the book was set in Flanders Pieck decided to visit there to soak up the atmosphere in the various towns. Above is an ink illustration from one of the chapters, A beautiful winter day in which the main character, Pallieter, goes out on a clear winter day and hears organ music. He heads towards the sound, but only sees two children playing with mud.

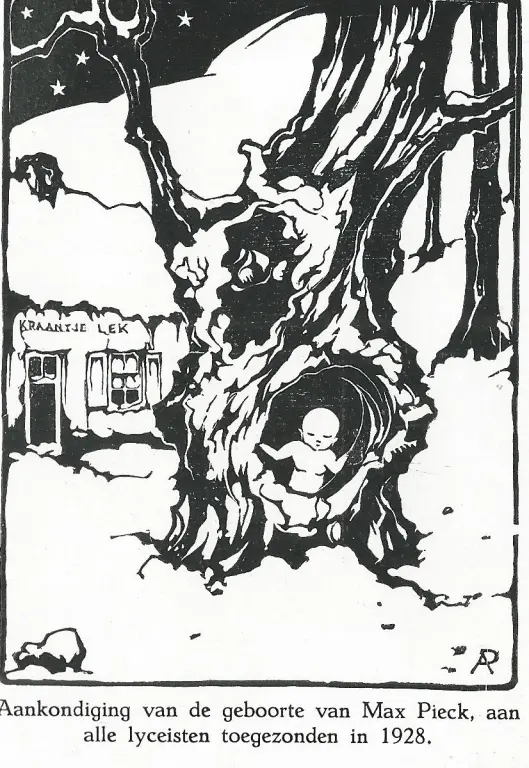

Anton Pieck’s way of announcing the birth of son Max Pieck sent to all the staff of the Kennemer Lyceum in 1928

In 1917, Anton Pieck met Jo van Poelvoorde, the sister of fellow soldier Hendrik van Poelvoorde. Jo was a teacher at the Royal Dutch Weaving School. Her first impressions of Anton were that he was friendly, but also taciturn and absent. Gradually he opened up more and became more talkative. Anton and Jo entered into a relationship and twenty-seven-year-old Anton Pieck married twenty-nine-year-old Josephina Johanna Lambertina (Jo) van Poelvoorde, on March 8th 1922 at The Hague. After the marriage the couple moved to Overveen. From their marriage three children were born, Elsa, Anneke and Max.

Harpenden Engeland by Anton Pieck

Throughout his life, Anton was an enthusiastic traveller and visited England, France, Ireland, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland, Austria, Italy, Poland and Morocco during which he built up a collection of sketches. He was a great lover of quaint buildings and had no interest in modern architecture. For him, it was a joy to study nature as well as picturesque cities and villages. He was so in love with Belgium and England that he termed them “his second mother countries” as their towns had not been “ruined” by modernisation as had happened in his homeland The Netherlands.

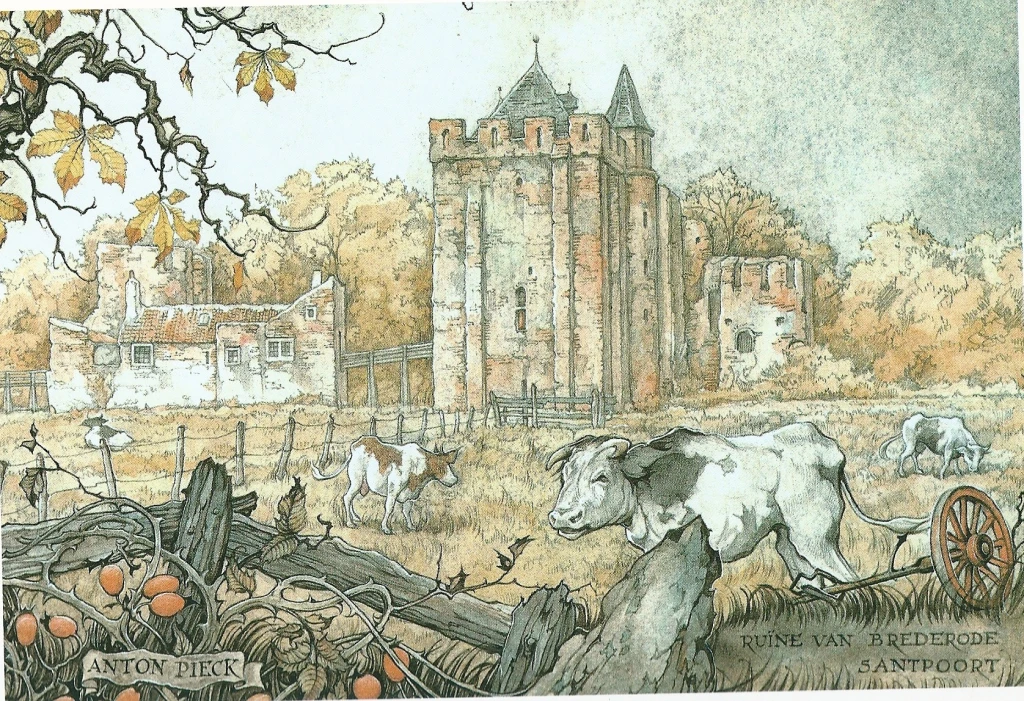

The ruins of Brederode in Santpoort by Anton Pieck (c.1950)

Anton Pieck was a twentieth century man as he only lived his first five years in the nineteenth century. Having said that, Pieck loved to look back with pleasure on what he considered to be a more appealing century – the nineteenth century.

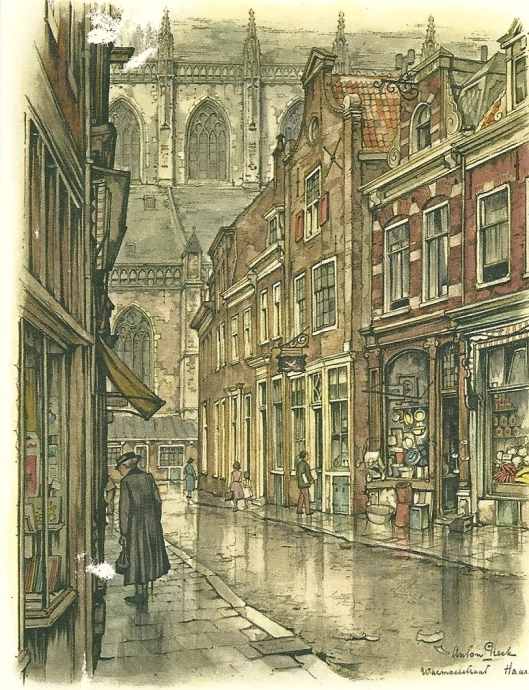

The Warmoesstraat, Amsterdam by Anton Pieck

He had fallen in love with the Dickensian era and had completed many paintings, drawings, etchings and engravings depicting Dickensian scenes. He depicted gentlemen in high hats or ladies adorned in crinoline, people taking coach rides, watching a magic lantern show or listening to barrel organs or chamber concerts. All such scenes gave him great pleasure and they all contributed to his artistic ideal. Anton Pieck was adamant that when it came to commissions, he would only accept those which allowed him to illustrate novels or short stories set in bygone days.

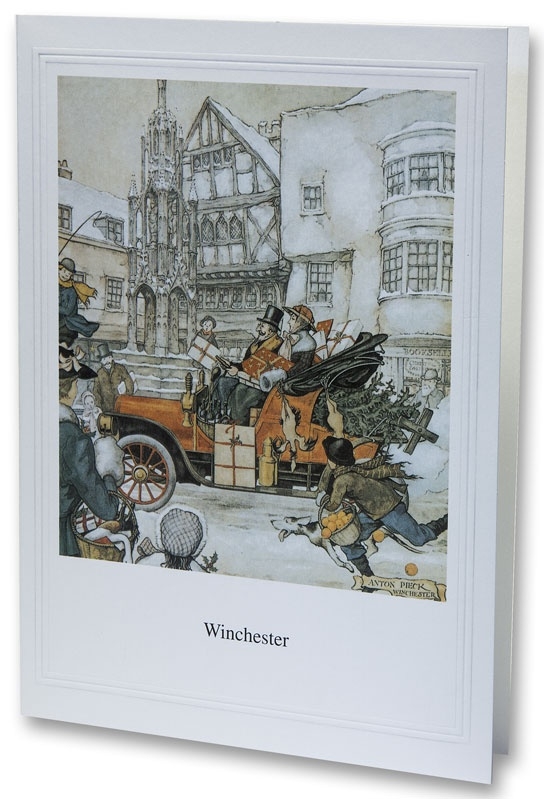

Greeting card of Winchester by Anton Pieck

What Pieck liked to depict were things which looked old or dilapidated. Buildings and their interiors which were crooked and looked ramshackle and run-down. For Anton, nothing was to look new or be built completely straight. Anton’s first visit to England appears to have been around 1937 when, on a voyage by ship to North Africa, he had managed to come ashore in Southampton and was able to made sketches of some of the old commercial buildings and to visit the city of Winchester where he sketched some of the old Tudor buildings and historic inns, one of which was turned into a greetings card.

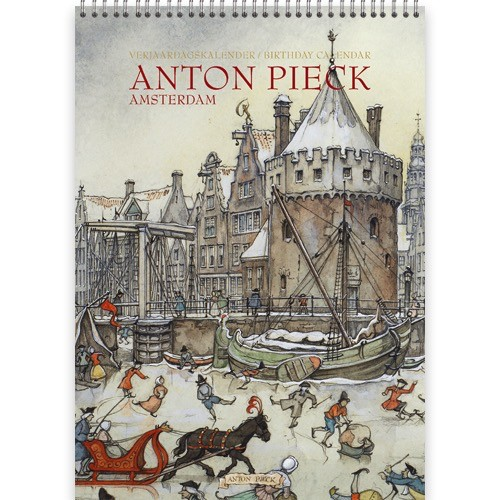

Besides prints and greeting cards, calendars were produced each year with a selection of Anton Pieck’s drawings.

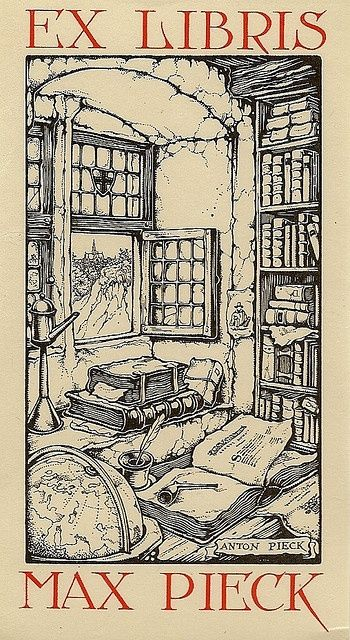

He would also produce a number of ex libris bookplates, a book owner’s identification label that was usually pasted to the inside front cover of a book. Above is one he created for his son, Max.

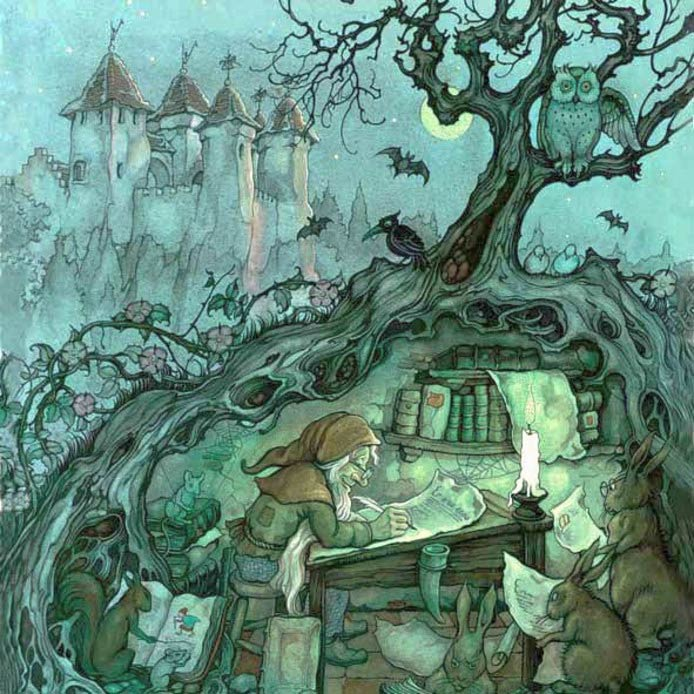

Anton Pieck’s vision for De Efteling

Anton Pieck’s work over the years and his popularity with the Dutch people was probably in the minds of the mayor of Loon op Zand, R.J. van der Heijden and filmmaker Peter Reijnders who had envisioned the building of a fantasy-themed amusement park, De Efteling, in Kaatsheuvel in the Dutch province of North Brabant in 1951, named after a 16th-century farm named Ersteling. The men approached Anton Pieck to design the theme park but he initially refused but later changed his mind on the proviso that only original materials are used for building the houses, such as coloured roof tiles and old stones. Anton then set about designing het Sprookjesbos, the fairy tale forest.

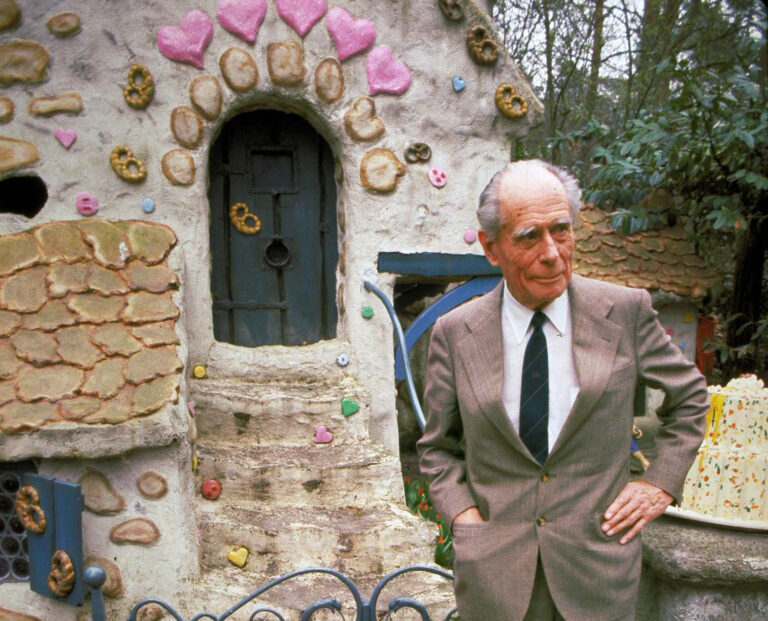

Anton Pieck at Efteling

Initially, the Fairy Tale Forest was designed and based upon ten different fairy tales, all of which were brought to life using original drawings by Pieck. Added to Pieck’s designs were mechanics, lighting and sound effects designed by the Dutch filmmaker Peter Reijnders. The life-sized dioramas, shown together in an atmospheric forest, were a incredible success and in 1952, the first full year, Efteling was open, it had 240,000 visitors and since 1978, the park has grown in size and is now become one of the most popular theme parks in the world.

Frau Holle at Efteling

Pieck designed all the houses, buildings and the special animatronic inhabitants who were inhabitants of the fairy tale forest, such as Little Red Riding Hood at her grandma’s house, Sleeping Beauty’s castle, Frau Holle’s well and Hansel and Gretel’s gingerbread house. Frau Holle, also known as Mother Hulda, is a German fairy tale character from the 1812 book, The Grimm Brothers’ Children’s and Household Tales (Grimms’ Fairy Tales).

Frau Holle by Anton Pieck

Frau Holle is often depicted shaking out bed linen over an outside balcony then it begins to snow. It is still a common expression in Hesse and Southern parts of the Netherlands and beyond to say “Hulda is making her bed” when it begins to snow. Like many other tales collected by the Brothers Grimm, the story of Frau Holle was also a moral tale explaining that hard work is rewarded and laziness is punished.

Anton Pieck Museum

Anton Pieck retired from teaching in 1960. He was made a Knight in the Order of Orange-Nassau. Pieck died on November 24th 1987 at the age of 92. Three years before his death the Anton Pieck Museum House for Anton Pieck was opened in Hattem, a municipality and a town in the eastern Netherlands.

Anton Pieck loved nature, the past and Dutch cityscapes. Sadly, during the course of the 20th century, large swathes of that old Netherlands he loved disappeared due to bombing during the war, the renovation and rejuvenation of the city centers from the 1960’s and the construction of the complicated road network. As a result, Anton became sad and depressed at what he witnessed during his latter years, saying in 1985:

“… Yes, I have known this country very well. What is still there now, I see as a mess of the past. That makes me sad, yes…”

Whatever you may think about the artistic style of Anton Pieck, one has to feel warmed by the depictions and undergo a desire to be back in olden days when life may have been simpler, or was it ?

The third of the Red Rose Girls was Jessie Willcox Smith. She became one of the most prominent female illustrators in the United States, during the celebrated ‘Golden Age of Illustration‘. Jessie was the eldest of the trio, born in the Mount Airy neighbourhood of Philadelphia, on September 6th 1863, the youngest of four children. She was the youngest daughter of Charles Henry Smith, an investment broker, and Katherine DeWitt Willcox Smith. Her father’s profession as an “investment broker” is often questioned as although there was an investment brokerage called Charles H. Smith in Philadelphia there is no record of it being run by anybody from Jessie Smith’s family. In the 1880 city census, Jessie’s father’s occupation was detailed as a machinery salesman. Jessie’s family was a middle-class family who always managed to make ends meet. Her family originally came from New York and only moved to Philadelphia just prior to Jessie’s birth. Despite not being part of the elite Philadelphia society, her family could trace their routes back to an old New England lineage. Jessie, like her siblings, were instructed in the conventional social graces which were considered a necessity for progression in Victorian society. It should be noted that there were no artists within the family and so as a youngster, painting and drawing were not of great importance to her. Instead her enjoyment was gained from music and reading. Jessie attended the Quaker Friends Central School in Philadelphia and when she was sixteen, she was sent to Cincinnati, Ohio to live with her cousins and finish her education.

The third of the Red Rose Girls was Jessie Willcox Smith. She became one of the most prominent female illustrators in the United States, during the celebrated ‘Golden Age of Illustration‘. Jessie was the eldest of the trio, born in the Mount Airy neighbourhood of Philadelphia, on September 6th 1863, the youngest of four children. She was the youngest daughter of Charles Henry Smith, an investment broker, and Katherine DeWitt Willcox Smith. Her father’s profession as an “investment broker” is often questioned as although there was an investment brokerage called Charles H. Smith in Philadelphia there is no record of it being run by anybody from Jessie Smith’s family. In the 1880 city census, Jessie’s father’s occupation was detailed as a machinery salesman. Jessie’s family was a middle-class family who always managed to make ends meet. Her family originally came from New York and only moved to Philadelphia just prior to Jessie’s birth. Despite not being part of the elite Philadelphia society, her family could trace their routes back to an old New England lineage. Jessie, like her siblings, were instructed in the conventional social graces which were considered a necessity for progression in Victorian society. It should be noted that there were no artists within the family and so as a youngster, painting and drawing were not of great importance to her. Instead her enjoyment was gained from music and reading. Jessie attended the Quaker Friends Central School in Philadelphia and when she was sixteen, she was sent to Cincinnati, Ohio to live with her cousins and finish her education.

Jessie Willcox Smith graduated from the Academy in June 1888. She looked back on her time at the Academy with a certain amount of disappointment. Although her technique had improved, she had hoped to be part of an artistic community in which artistic collaboration would be present but instead she found dissention, scandal and in the wake of the Eakins’ scandal, institutionalized isolation. Jessie talked very little about her time at the Academy. It had been a turbulent time and she had hated conflict as it unnerved her and made her extremely distressed. This desperation to avoid any kind of conflict in her personal and professional life revealed itself in her idealistic and often blissful paintings. Jessie wanted to believe life was just a period of happiness.

Jessie Willcox Smith graduated from the Academy in June 1888. She looked back on her time at the Academy with a certain amount of disappointment. Although her technique had improved, she had hoped to be part of an artistic community in which artistic collaboration would be present but instead she found dissention, scandal and in the wake of the Eakins’ scandal, institutionalized isolation. Jessie talked very little about her time at the Academy. It had been a turbulent time and she had hated conflict as it unnerved her and made her extremely distressed. This desperation to avoid any kind of conflict in her personal and professional life revealed itself in her idealistic and often blissful paintings. Jessie wanted to believe life was just a period of happiness.

Our hopes were soon dashed as we set about reading The History of Mr Polly which I remembered to be both turgid and depressing but there again I have to admit I was never an avid reader. The Shakespearean play was the Merchant of Venice which proved a lucky choice and one which I especially enjoyed when we looked at it in depth. Then came the poem. Poetry was anathema to sixteen year old boys and “boys don’t do poetry” was our class mantra and one needs to remember that our school was an all-boys one. Add to that the feeling of gloom about embarking on reading and learning lines of the poem for furthermore this chosen poem, which we had to study was not a short one with just a few stanzas but an extremely long one. It was The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, which was the longest major poem by the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and one he completed and had published in 1798. Unbelievably it proved to be my favourite part of the English Literature exam syllabus.

Our hopes were soon dashed as we set about reading The History of Mr Polly which I remembered to be both turgid and depressing but there again I have to admit I was never an avid reader. The Shakespearean play was the Merchant of Venice which proved a lucky choice and one which I especially enjoyed when we looked at it in depth. Then came the poem. Poetry was anathema to sixteen year old boys and “boys don’t do poetry” was our class mantra and one needs to remember that our school was an all-boys one. Add to that the feeling of gloom about embarking on reading and learning lines of the poem for furthermore this chosen poem, which we had to study was not a short one with just a few stanzas but an extremely long one. It was The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, which was the longest major poem by the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and one he completed and had published in 1798. Unbelievably it proved to be my favourite part of the English Literature exam syllabus.

And so to the Samuel Coleridge Taylor poem, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. Doré was excited about illustrating the poem, so much so he had completed the designs for the illustrations before a deal had been struck with the publisher. The wooden blocks he used for the illustrations were very large and cost Doré a lot of money and unlike previous engravings he took control of the supervision of them. Doré believed that this was his greatest work but unfortunately for him, its sales recouped him only slowly for his large initial outlay. It was first published in England and soon editions appeared in France, Germany and America.

And so to the Samuel Coleridge Taylor poem, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. Doré was excited about illustrating the poem, so much so he had completed the designs for the illustrations before a deal had been struck with the publisher. The wooden blocks he used for the illustrations were very large and cost Doré a lot of money and unlike previous engravings he took control of the supervision of them. Doré believed that this was his greatest work but unfortunately for him, its sales recouped him only slowly for his large initial outlay. It was first published in England and soon editions appeared in France, Germany and America. Samuel Coleridge Taylor did not set his poem in any one period but as an illustrator, Doré had to be more precise and he chose a medieval setting for the wedding feast at the start of the poem.

Samuel Coleridge Taylor did not set his poem in any one period but as an illustrator, Doré had to be more precise and he chose a medieval setting for the wedding feast at the start of the poem. It is an ancient Mariner,

It is an ancient Mariner, With sloping masts and dipping prow,

With sloping masts and dipping prow, And through the drifts the snowy clifts

And through the drifts the snowy clifts At length did cross an Albatross:

At length did cross an Albatross: However for some unknown reason the Ancient Mariner shot the albatross with his crossbow.

However for some unknown reason the Ancient Mariner shot the albatross with his crossbow. Water, water, every where,

Water, water, every where, There passed a weary time. Each throat

There passed a weary time. Each throat The ghostly hulk approaches their ship and on board are two figures, a skeletal Death and a deathly pale female, Night-mare Life-in-Death and the two are playing dice for the souls of the crew members. Death wins the lives of all the crew members, all except for the Ancient Mariner, whose life is won by Night-mare Life-in-Death. It is the name of this character that allows us to know the fate of the Ancient Mariner – a fate worse than death, a living death, was to be his punishment for killing the albatross.

The ghostly hulk approaches their ship and on board are two figures, a skeletal Death and a deathly pale female, Night-mare Life-in-Death and the two are playing dice for the souls of the crew members. Death wins the lives of all the crew members, all except for the Ancient Mariner, whose life is won by Night-mare Life-in-Death. It is the name of this character that allows us to know the fate of the Ancient Mariner – a fate worse than death, a living death, was to be his punishment for killing the albatross. The Ancient Mariner is the sole survivor of the ill-fated crew. The bodies of the dead crew members lay around the deck with their eyes staring at the Ancient Mariner. The Ancient Mariner recounts how he felt, how he wanted to die but was not allowed that luxury.

The Ancient Mariner is the sole survivor of the ill-fated crew. The bodies of the dead crew members lay around the deck with their eyes staring at the Ancient Mariner. The Ancient Mariner recounts how he felt, how he wanted to die but was not allowed that luxury.