The great portrait artist and his beautiful muse and model

“…When I first got undressed to pose for him, he looked me up and down with a critical eye. ‘ Perfect breasts. Not too big, not too small. You can thank your Indonesian forebears for those’. We’d known each other for about a month, and already we were perfectly at ease with each other, as if we’d known each other all our lives…”

Renske Mann from her book, The Girl in the Green Jumper

Renske was overjoyed by Cyril’s words. Although she didn’t believe his words were utterances of flattery and just simple facts, nevertheless the words made her happy and made her love him even more.

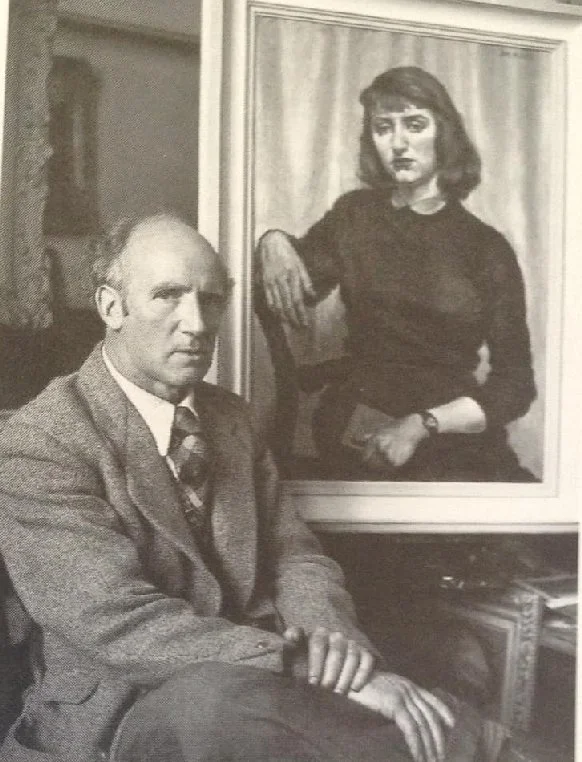

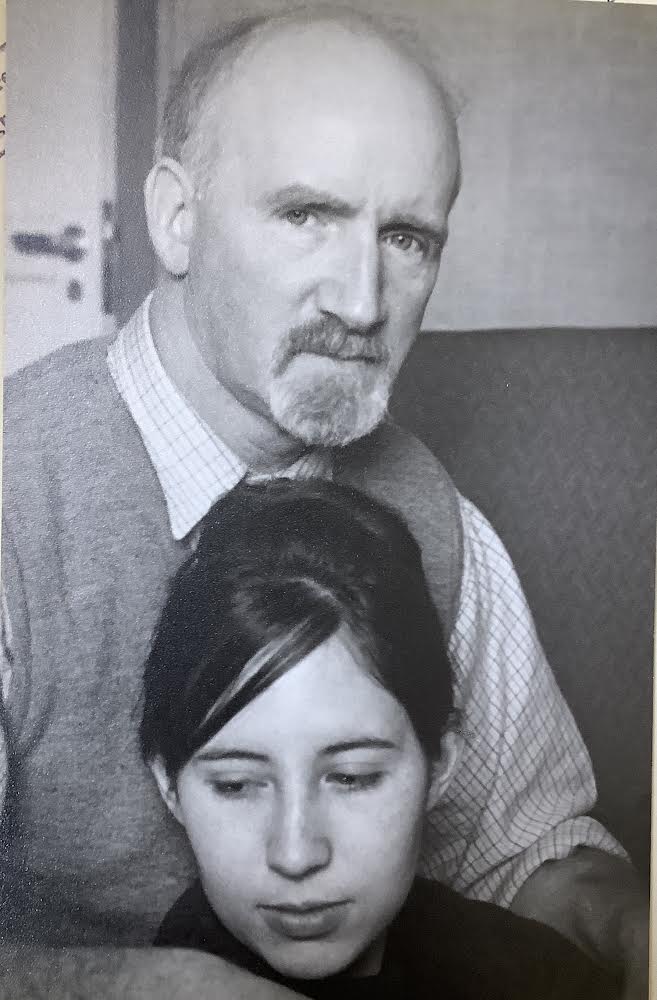

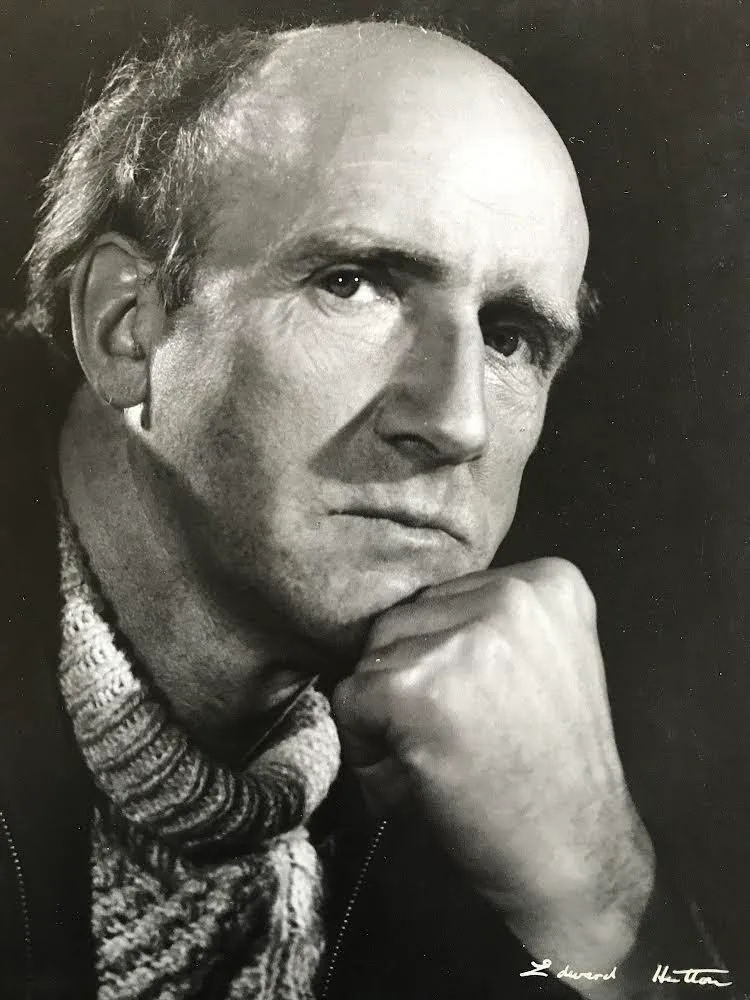

Cyril Mann (1960). Photograph by Edward Hutton.

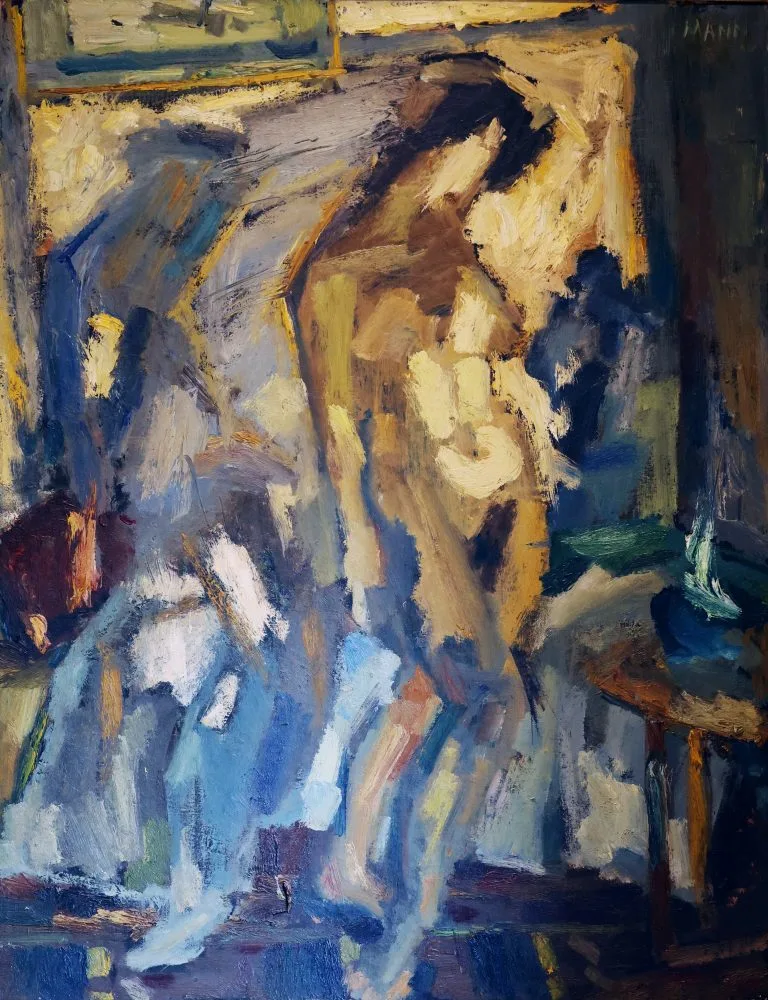

Throughout his career Cyril painted many portraits, self-portraits and in the 1960s Cyril Mann completed a number of nude depictions using Renske as his model.

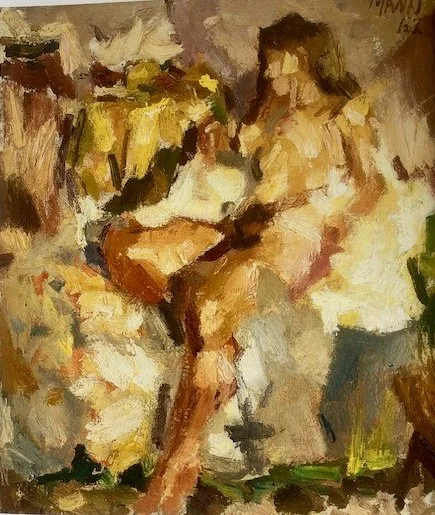

Ecstasy by Cyril Mann (1963)

One such nude portrait, using her as a model, was completed in 1963 and entitled Ecstasy. Renske remembers the morning he began this work. In her book, The Girl in the Green Jumper, she describes the setting:

“…Cyril mostly painted in the morning. The minute he drew the curtains he knew when the weather was set to last. As the sun rose, it cast shadows from the Crittall windows [steel framed windows] across my nude body on our single bed. He stared at me, grunting and squinting ‘Stay put and take a comfortable pose’ he ordered. I knew by then that there was no such thing: every pose would turn into agony in time…”

It was not just about her body or pose it was also about the sunlight streaming through the window. It was of the utmost importance to Cyril to capture the dynamic effects of the rays of the sun as they bounced off every surface, from walls on to Renske’s body and back. He was like a man possessed. Tables and chairs had to be moved out to make a working space. He would shuffle around the tight spaces never lifting the gaze from Renske’s body. She moved to get comfortable on the bed and started to doze off only to be woken abruptly by Cyril who rudely told her “not to go fucking asleep”. Throughout painting Renske said he would not stop talking, all the while explaining what he was doing. He was adamant that he had to block in the light areas first as they were more important, not the mid-tones or darks. Cyril compared Renske to the RA models he had once used saying:

“…Models at the RA haven’t a clue. They just sit on a chair. Students have to group around a podium. If you are in the wrong spot, you’re fucked. At least you know how to make your body look interesting…”

Cyril had been introduced to the famous English television personality, Denis Norden, who on seeing the painting told Cyril that he should give it the title Ecstasy. Cyril and Renske had hoped that Norden would buy the painting but he didn’t but their mutual friend, Peter Davis, who had introduced Denis Norden to them suggested they just give Norden the painting for nothing as the celebrity owning one of Cyril’s paintings would be added kudos. However Cyril was appalled by the suggestion and simply said ‘to hell with that’.

Modern Venus (c.1963)

One morning Cyril Mann came into the bedroom where is wife, naked, had just risen from bed.. He flings back the curtains and the sunlight streams in, illuminating her. He screamed at her not to move and at the same time drags into the room a large canvas and starts to paint her portrait. She remembers that her shadow was cast against the wall as she rose from the vey messy jumble of bedclothes strewn on the bed. She is standing facing him with her left arm above her head which in that posture soon becomes numb. She balanced by standing one foot in front. Their blue alarm clock on their round bedside table glistens in the sun. He told her that she was a Modern Venus. Not rising from a seashell but from the sheets and blankets. The painting Modern Venus is complete.

Reclining Nude in Sunlight by Cyril Mann (1962)

In Reclining Nude in Sunlight, Cyril Mann omits detail as he just wants to depict and render light as a dynamic force. He used large hog’s-hair paintbrushes so that he could rapidly cover the canvas, and so focus on the light and how the sunlight fell and reflected on Renske’s nude body as it swiftly crossed their room.

Golden Torso by Cyril Mann (1961)

Golden Torso was completed in 1961 and when the author and art critic John Berger saw it he immediately recommended it for the Granada TV Art Collection which was recognised as probably having the third best corporate collection in Britain. Unfortunately for Berger the painting had already been snapped up by another collector and Berger reluctantly chooses another picture for his sponsor.

Self portrait with Double Nude by Cyril Mann (1965)

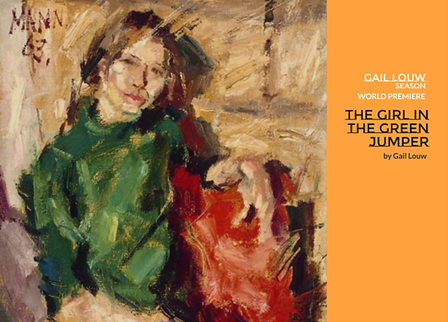

Probably the best-known portraits Cyril completed of Renske was The Girl in the Green Jumper, one with her fully clothed. His self-portrait can be seen in the background, hanging on the wall.

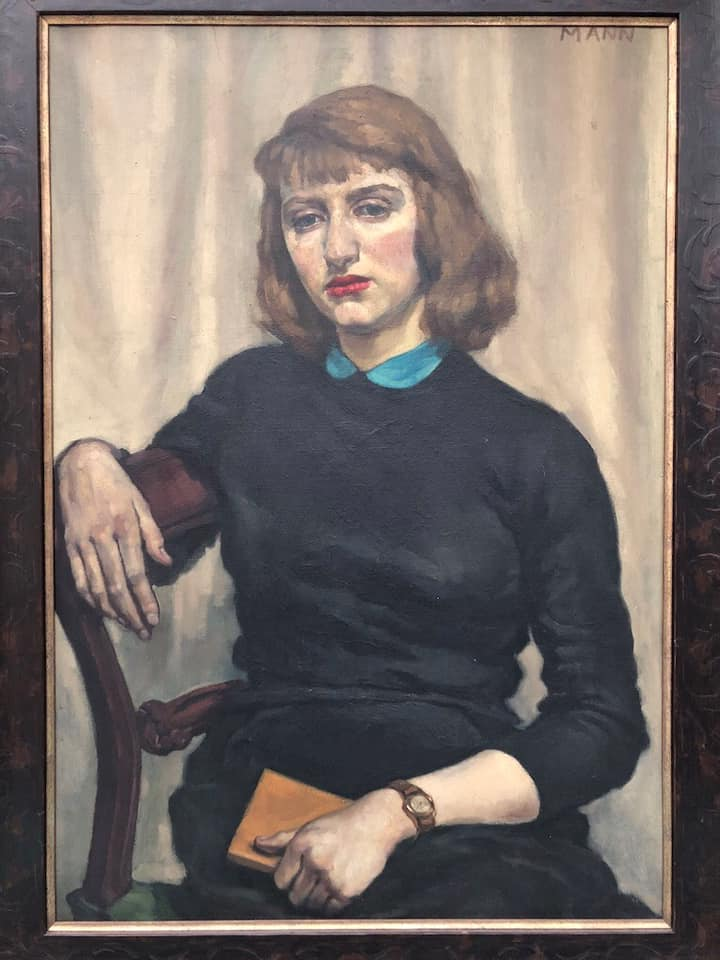

The Girl in the Green Jumper by Cyril Mann (1963)

In the painting, The Girl in the Green Jumper, we see Renske perched on the narrow wooden armrest of their red chair, which she recalled made sitting still very difficult and painful, much to Cyril’s annoyance. She said that posing for Cyril required a good deal of concentration and willpower. The depiction came about when Cyril was admiring the green of her jumper which he commented looked so much more intense, seen against the red upholstery of their newly-purchased G-Plan suite. Renske, like many, queried whether it is a portrait or a study of sunlight blazing on to her through the window, striking her face and bouncing all over the room. She commented to her husband that her hands were just fingerless smears of paint but he replied that that was true abstraction. Abstraction he said was “to leave out” and abstract art is not actually abstract at all and should be better termed as “non-figurative”.

Amanda Mann has followed in her father Cyril Mann’s footsteps and is now also a talented artist. Here Amanda is seen with the painting that inspired her mother Renske Mann’s memoir “The Girl In The Green Jumper: My life with Cyril Mann”.

Cyril Mann, besides the nude depictions of his wife and self-portraits, completed many portraits of his family and friends which highlight what, he as a talented portrait artist, could produce. There is no doubt that he could have been a wealthy portrait painter. Alas he only rarely painted portraits of people outside the family as he said he could not accept portraiture commissions where he was supposed to flatter his sitter, which he believed was often the prerequisite for being given the commission.

Portrait of Sylvia, aged 3, tearfully clutching her doll, by Cyril Mann (1943)

Sylvia, Cyril’s first daughter, would recount on a number of occasion the memory of sitting for her father for the portrait. She said the agony and boredom of sitting still for hours, clutching the doll still haunted her.

Portrait of Sylvia, by Cyril Mann (c.1957) Collection Gideon Dewhirst (Sylvia’s son and Cyril’s grandson)

Cyril Mann with his portrait of Sylvia Mann.

It is hard to judge the mood of the sitter. Sylvia was then aged seventeen and it was the time prior to her attending Keele University. It seems she is somewhat lost in her own thoughts. The depiction shows her holding a book, signifying her love of literature. After university she would go on to become a published author, poet and playwright. Sylvia died in 2006.

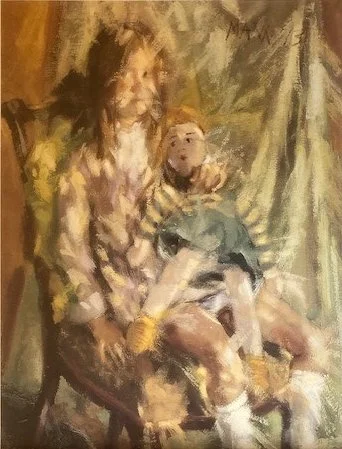

Amanda, aged 4, with Doll by Cyril Mann (1973)

Cyril and Renske’s four year old daughter, Amanda, was posed sitting on a chair holding her doll. It was a similar depiction to Cyril’s portrait of his first-born daughter, Sylvia, which he completed in 1943, also with a doll.

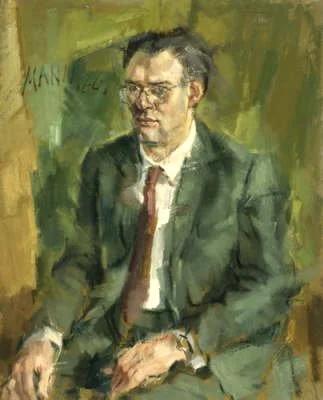

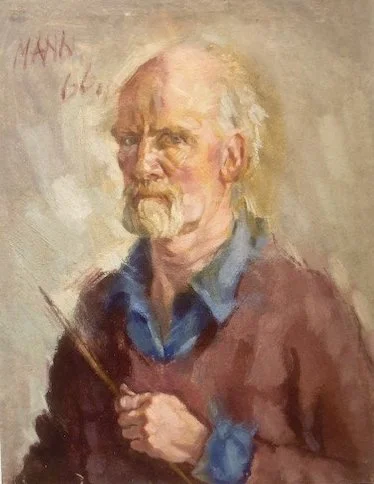

Portrait of David Hardisty by Cyril Mann (1966)

David Hardisty was a young lawyer working as a patent agent. He had seen and fell in love with one of Cyril’s floral paintings which were on display at the Rawinski Gallery in London. Hardisty, who had recently married, could not afford the £300 price tag. Not to be deterred he went to Bevin Court to ask Cyril if he could buy the painting in fifteen £20 instalments. Cyril agreed and during the following years David bought more of Cyril’s paintings. In the portrait, sunlight once again takes precedence over form in Cyril’s rendering. It plays across David’s features and on his suit, tie and hands. Time must have been at a premium for Cyril as the portrait was completed in only six two-hour sittings.

My Student, Vic Singh by Cyril Mann (1962)

When Renske went to the art class in December 1959 and met Cyril Mann for the frst time, one of his students that evening was Vic Singh. whom Renske remembered as being an extremely handsome young man,. His mother was Austrian and his father was an Indian politician. Singh went on to become a photographer. One day he called around to Bevin Court and Cyril persuaded him to pose for a portrait. He agreed and posed, one foot raised with his elbow resting across his knee while stretching one arm towards the bookcase in order to maintain his balance. He was exhausted by the time Cyril had completed the portrait.

Portrait of Ernest Groome (1971)

In 1960, Renske, like her husband, began to worry about the lack of sales of his paintings and suggested he took some of his work to Hyde Park Corner where many artists hung their work on the railings. Cyril was horrified with this idea saying that serious artists would not dream of hawking their wares in such a way. Renske, however, said that if he wouldn’t do it, she would. She arrived at Hyde Park Corner and found some spaces on the railings where she could hang Cyril’s artwork but she had forgotten to bring string or hooks to complete her task. She was rescued by a young Irishman, Ernest Groome, an aspiring young artist who had been working as a touring pub entertainer. He managed to find hooks and string and he and Renske hung Cyril’s paintings on the railings.

Cyril first painted Ernest Groome’s portrait in 1961 shortly after the Hyde Park Corner meeting and ten years later completed another portrait of Groome. In this portrait Groome is in Renske and Cyril’s home. The red shade of the standard lamp picks up the colour of his shirt, casting a strong solid shadow against the wall behind him.

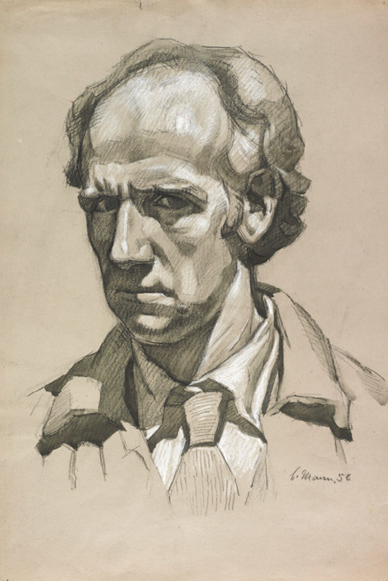

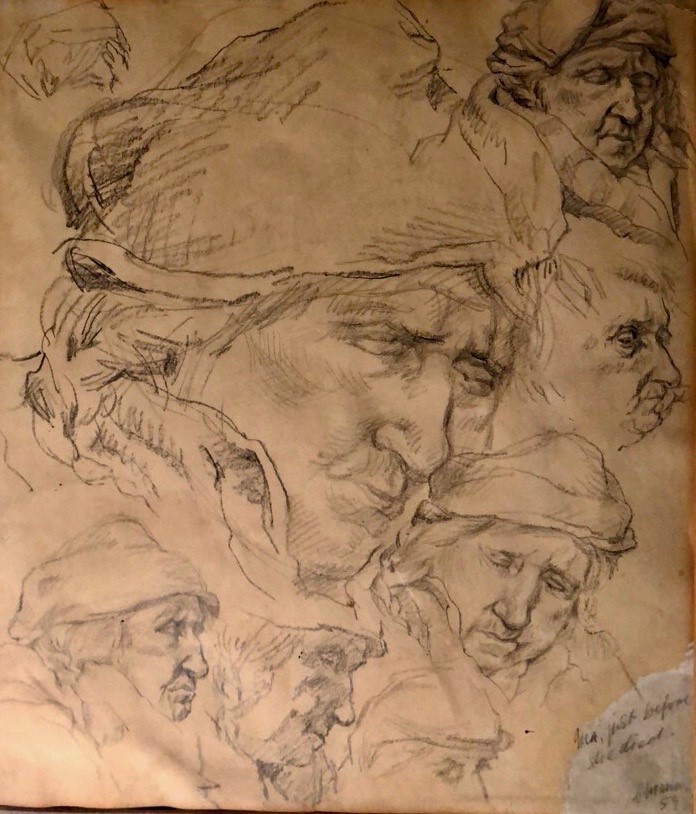

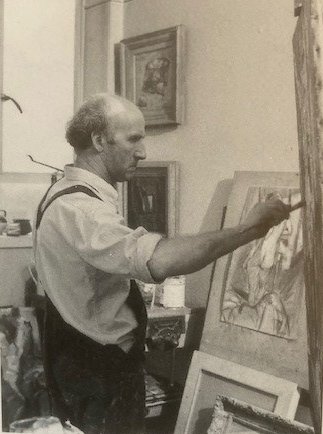

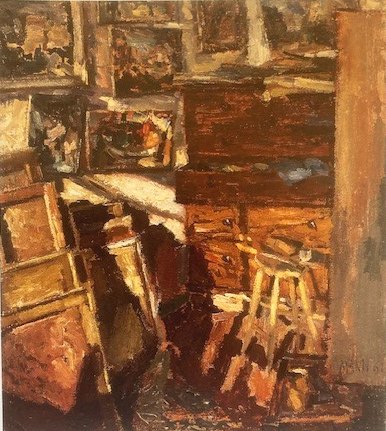

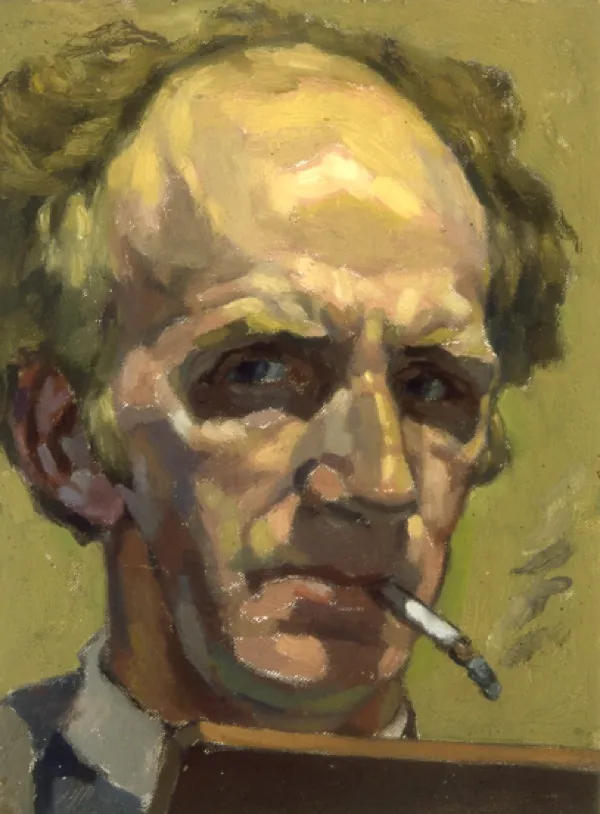

Self portrait by Cyril Mann

Cyril left behind many self-portraits which capture his many moods.

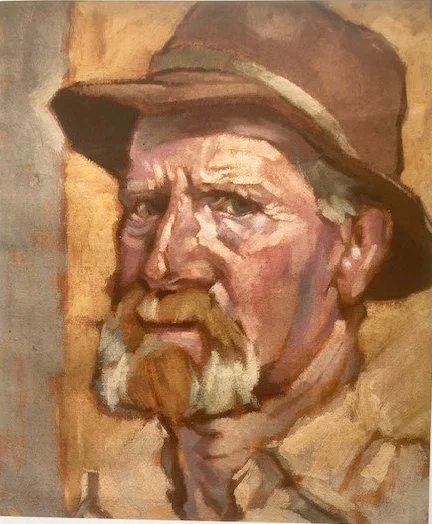

Self-Portrait with Hat by Cyril Mann (c.1968)

It is a very worried-looking Cyril Man who stares out at us in his 1968 Self-Portrait with Hat. He seems to have the cares of the world on his shoulders. It is 1968 and Renske is pregnant with her daughter Amanda, Renske, whose job was bringing financial stability to the household, was having to give up her job to have the baby. How were they going to cope? Could Cyril sell more of his work? All of these and many more questions were probably racing around Cyril’s head at the time of the self-portrait.

Self-Portrait with a Brush by Cyril Mann (1966)

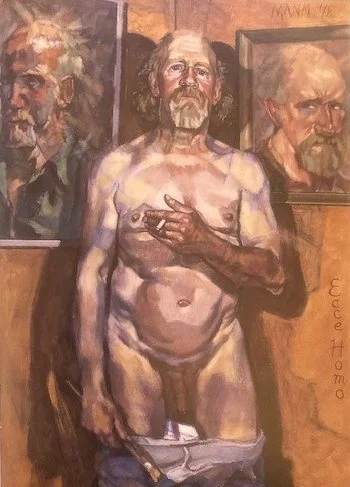

The most controversial self-portrait came in 1978 under the title Ecce Homo. Ecce homo, meaning “behold the man” are, according to the Gospel of St John, the Latin words used by Pontius Pilate when he presented a scourged Jesus, bound and crowned with thorns, to a hostile crowd shortly before his Crucifixion.

Ecce Homo by Cyril Mann (1978)

Ecce Homo was one of last self-portraits painted by Cyril Mann. He died a year later. His state of mind, at the time he painted his own portrait, was unstable but there was also a sense of defiance about this depiction. A sense that he was master of his own destiny. It is in a way a mirror of his great creative energy which throughout his life shone brightly and was never dimmed by his detractors. Having given up smoking on doctor’s orders he had reverted to that habit and the portrait shows him defiantly holding a cigarette. It was another way of showing that he, and he alone, would make decisions about himself. His rebellious posture and the title he gave the work was his way of reasoning that he, like Christ, had been persecuted and in a way crucified by art critics and gallery owners. He adamantly believed that the reason he never achieved the success he deserved during his life was due to others and not himself. In the background, we see flanking him two earlier self-portraits and their positioning symbolises the thieves crucified on either side of Christ.

……. to be continued.

It would not have been possible for me to put together this and following blogs about the artist, Cyril Mann, without information gleaned from a number of sources:

The comprehensive biography of Cyril Mann, The Sun is God by John Russell Taylor

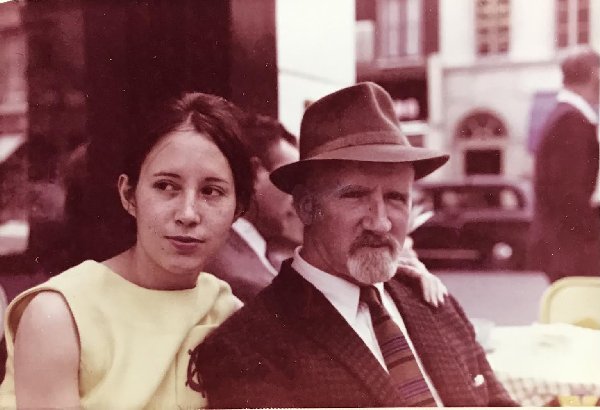

Renske Mann with her book The Girl in the Green Jumper, My life with the artist Cyril Mann

The intimate autobiography of Cyril Mann’s life by his second wife Renske, entitled The Girl in the Green Jumper.

Renske Mann and Natalie Ava Nasr, the lady playing the role of Renske in the play.

Peter Tate who plays Cyril Mann, Christian Holder, director of the play and Natalie Ava Nasr, who plays Renske in the play The Girl in the Green Jumper.

This autobiography has now been turned into a play which receives its World Premiere on Wednesday March 13th at the Playground Theatre, London, 8 Latimer Rd, London W10 6RQ. It runs until March 24th.

Finally, and most importantly I owe many thanks to Renske Mann herself who provided me with information and photographs appertaining to her late husband Cyril.

Piano Nobile Gallery London for information and pictures.