Gustave Doré and the Rime of the Ancient Mariner.

The subject of my blog today reflects moments of my past life, from the days when I spent years journeying across the oceans and earlier when, at the age of sixteen, I had to sit the national exam in English Literature. The examination was based on a book, a Shakespearian play, and a poem, all of which, we had to read, over and over again and dissect each into bits of minutiae. My classmates and I were delighted to find the book we had to read and digest was a novel by H.G.Wells. We had all heard of and/or read his Time Machine and War of the Worlds so we looked forward to the book set by the exam board.

Our hopes were soon dashed as we set about reading The History of Mr Polly which I remembered to be both turgid and depressing but there again I have to admit I was never an avid reader. The Shakespearean play was the Merchant of Venice which proved a lucky choice and one which I especially enjoyed when we looked at it in depth. Then came the poem. Poetry was anathema to sixteen year old boys and “boys don’t do poetry” was our class mantra and one needs to remember that our school was an all-boys one. Add to that the feeling of gloom about embarking on reading and learning lines of the poem for furthermore this chosen poem, which we had to study was not a short one with just a few stanzas but an extremely long one. It was The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, which was the longest major poem by the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and one he completed and had published in 1798. Unbelievably it proved to be my favourite part of the English Literature exam syllabus.

Our hopes were soon dashed as we set about reading The History of Mr Polly which I remembered to be both turgid and depressing but there again I have to admit I was never an avid reader. The Shakespearean play was the Merchant of Venice which proved a lucky choice and one which I especially enjoyed when we looked at it in depth. Then came the poem. Poetry was anathema to sixteen year old boys and “boys don’t do poetry” was our class mantra and one needs to remember that our school was an all-boys one. Add to that the feeling of gloom about embarking on reading and learning lines of the poem for furthermore this chosen poem, which we had to study was not a short one with just a few stanzas but an extremely long one. It was The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, which was the longest major poem by the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and one he completed and had published in 1798. Unbelievably it proved to be my favourite part of the English Literature exam syllabus.

I was in London last week and visited Camden Lock which has a great market and a plethora of “arty” shops including an excellent second-hand book shop where I found a number of books to buy, one of which was The Rime of The Ancient Mariner with forty-two illustrations by Gustave Doré. My blog today looks at Gustave Doré and some of the illustrations used in the book.

Paul-Gustave Doré was an Alsatian, born on January 6th, 1832, in Strasbourg. He became known as one of the most prolific and successful book illustrators of the late 19th century, whose high-spirited and somewhat strange fantasy-fashioned sizeable dreamlike scenes were widely loved during the Victorian period.

Doré was considered by many as a child genius when it came to his artistic ability. By age five, he was creating drawings that were mature beyond his years. In his late teenage years, he created several text comics, like his 1847 “comic” Les Travaux d’Hercule. Others followed and so well-liked were his works that he won a commission to illustrate books by Cervantes, Milton, and Dante.

Honoré de Balzac’s Les Contes drolatiques (Droll Stories) were illustrated by Gustave Doré

In 1848, when he was fifteen years old, Doré, went to Paris and began working as a caricaturist for the French paper Le Journal pour rire (Journal for laughs) as well as producing, over the next six years, several albums containing his lithographs.

His most accomplished work could be seen in his illustrations in such books as the 1854 edition of the Oeuvres de Rabelais, the 1855 edition of Honoré de Balzac’s Les Contes drolatiques (Droll Stories), and the 1861 edition of Inferno of Dante.

He also painted many large compositions of a religious, mythological, or historical character such as his 1869 work, Andromeda. The painting depicts Andromeda, the daughter of the Aethiopian king Cepheus and his wife Cassiopeia. When Cassiopeia’s boasts that Andromeda is more beautiful than the Nereids, the sea nymphs, Poseidon sends the sea monster Cetus to ravage Andromeda as divine punishment. Andromeda is stripped and chained naked to a rock as a sacrifice to sate the monster but is saved from death by Perseus.

One of my favourite paintings by Doré was his spectacular landscape scene entitled Glen Massan. Doré first visited the Scottish Highlands in 1873 on a salmon fishing trip with his good friend Colonel Teesdale. However, it turned out that Doré preferred to paint rather than fish and was inspired by the beauty of the Highland landscape, so much so, he returned to northern Scotland the following year. This painting, of Glen Massan near Dunoon, is a large canvas painted in a romantic Victorian style. I like the way Doré has depicted shafts of light penetrating the billowing clouds and lighting up parts of the valley.

And so to the Samuel Coleridge Taylor poem, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. Doré was excited about illustrating the poem, so much so he had completed the designs for the illustrations before a deal had been struck with the publisher. The wooden blocks he used for the illustrations were very large and cost Doré a lot of money and unlike previous engravings he took control of the supervision of them. Doré believed that this was his greatest work but unfortunately for him, its sales recouped him only slowly for his large initial outlay. It was first published in England and soon editions appeared in France, Germany and America.

And so to the Samuel Coleridge Taylor poem, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. Doré was excited about illustrating the poem, so much so he had completed the designs for the illustrations before a deal had been struck with the publisher. The wooden blocks he used for the illustrations were very large and cost Doré a lot of money and unlike previous engravings he took control of the supervision of them. Doré believed that this was his greatest work but unfortunately for him, its sales recouped him only slowly for his large initial outlay. It was first published in England and soon editions appeared in France, Germany and America.

Samuel Coleridge Taylor did not set his poem in any one period but as an illustrator, Doré had to be more precise and he chose a medieval setting for the wedding feast at the start of the poem.

Samuel Coleridge Taylor did not set his poem in any one period but as an illustrator, Doré had to be more precise and he chose a medieval setting for the wedding feast at the start of the poem.

The opening setting for the poem is a path leading to a church where three of wedding party are heading. An elderly man with a grey beard, the Ancient Mariner, halts them to tell his tale. Two escape his clutches but the third is trapped and made to listen.  It is an ancient Mariner,

It is an ancient Mariner,

And he stoppeth one of three.

“By thy long grey beard and glittering eye,

Now wherefore stopp’st thou me?

“The Bridegroom’s doors are opened wide,

And I am next of kin;

The guests are met, the feast is set:

May’st hear the merry din.”

The old sailor recounts how the sea voyage had started well but soon the ship was being drawn southward by a storm and the men had lost control of the vessel.

With sloping masts and dipping prow,

With sloping masts and dipping prow,

As who pursued with yell and blow

Still treads the shadow of his foe

And forward bends his head,

The ship drove fast, loud roared the blast,

And southward aye we fled.

Soon the Ancient Mariner’s ship was trapped in the Antarctic ice with no hope for survival.

And through the drifts the snowy clifts

And through the drifts the snowy clifts

Did send a dismal sheen:

Nor shapes of men nor beasts we ken —

The ice was all between.

The ice was here, the ice was there,

The ice was all around:

It cracked and growled, and roared and howled,

Like noises in a swound!

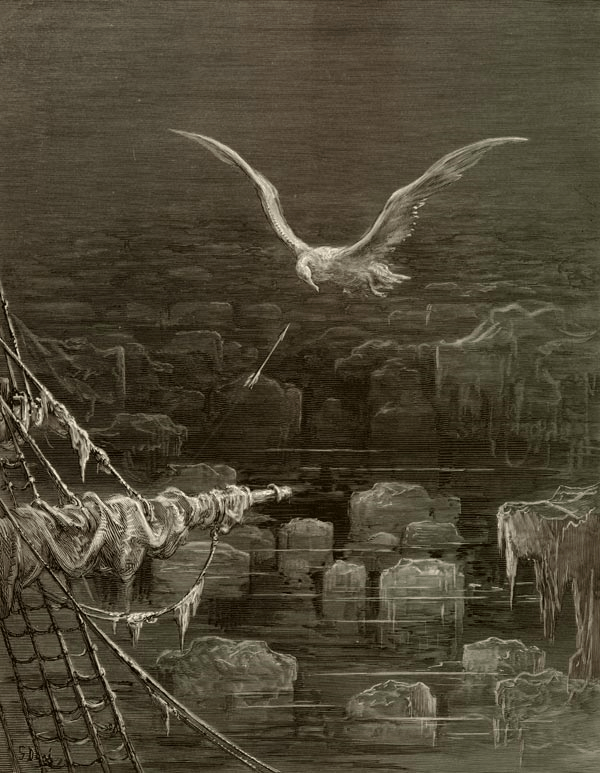

The Ancient Mariner recalls how the sailors believed they were doomed and all hope had gone – until the arrival of an albatross, which came each day and was fed by the sailors. The bird then led the ship and the sailors away from their icy prison and all aboard celebrated their good fortune.

At length did cross an Albatross:

At length did cross an Albatross:

Thorough the fog it came;

As if it had been a Christian soul,

We hailed it in God’s name.

It ate the food it ne’er had eat,

And round and round it flew.

The ice did split with a thunder-fit;

The helmsman steered us through!

And a good south wind sprung up behind;

The Albatross did follow,

And every day, for food or play,

Came to the mariners’ hollo!

However for some unknown reason the Ancient Mariner shot the albatross with his crossbow.

However for some unknown reason the Ancient Mariner shot the albatross with his crossbow.

“God save thee, ancient Mariner!

From the fiends, that plague thee thus! —

Why look’st thou so?”— With my cross-bow

I shot the ALBATROSS.

At first the sailors, despite condemning the old mariner for his action, seemed to be pleased that the south wind which had been mustered up by the albatross was still with them and they had left the cold waters of Antarctica and approached the warm waters of the Equator. All was good with the crew and their ship, but then the wind dropped and the ship was becalmed.

Down dropt the breeze, the sails dropt down,

’Twas sad as sad could be;

And we did speak only to break

The silence of the sea!

All in a hot and copper sky,

The bloody Sun, at noon,

Right up above the mast did stand,

No bigger than the Moon.

Day after day, day after day,

We stuck, nor breath nor motion;

As idle as a painted ship

Upon a painted ocean.

Water, water, every where,

Water, water, every where,

And all the boards did shrink;

Water, water, every where,

Nor any drop to drink.

The very deep did rot: O Christ!

That ever this should be!

Yea, slimy things did crawl with legs

Upon the slimy sea.

The becalmed ship was surrounded by evil creatures of the sea and soon the blame for their misfortune fell on the Ancient Mariner for killing the albatross. Close to death they suddenly spot a shape on the horizon – could it have come to their rescue?

There passed a weary time. Each throat

There passed a weary time. Each throat

Was parched, and glazed each eye.

A weary time! a weary time!

How glazed each weary eye,

When looking westward, I beheld

A something in the sky.

At first it seemed a little speck,

And then it seemed a mist:

It moved and moved, and took at last

A certain shape, I wist.

The ghostly hulk approaches their ship and on board are two figures, a skeletal Death and a deathly pale female, Night-mare Life-in-Death and the two are playing dice for the souls of the crew members. Death wins the lives of all the crew members, all except for the Ancient Mariner, whose life is won by Night-mare Life-in-Death. It is the name of this character that allows us to know the fate of the Ancient Mariner – a fate worse than death, a living death, was to be his punishment for killing the albatross.

The ghostly hulk approaches their ship and on board are two figures, a skeletal Death and a deathly pale female, Night-mare Life-in-Death and the two are playing dice for the souls of the crew members. Death wins the lives of all the crew members, all except for the Ancient Mariner, whose life is won by Night-mare Life-in-Death. It is the name of this character that allows us to know the fate of the Ancient Mariner – a fate worse than death, a living death, was to be his punishment for killing the albatross.

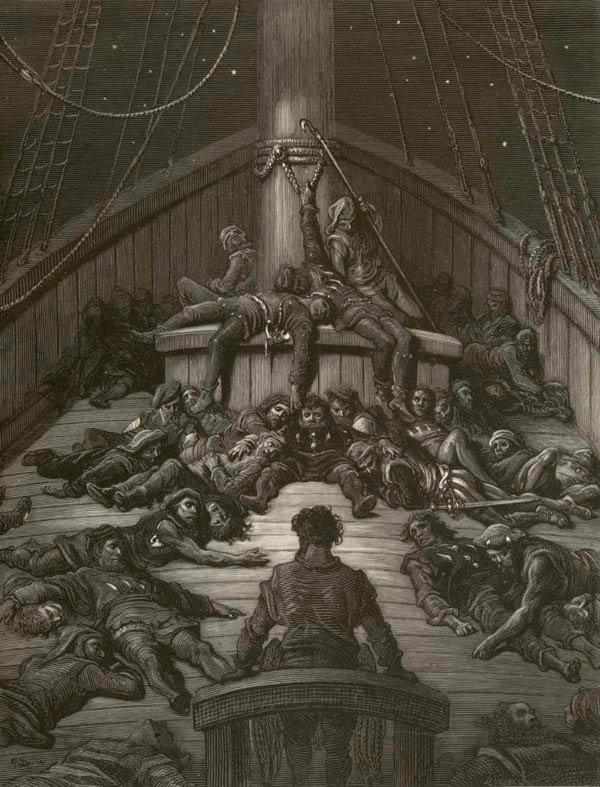

The Ancient Mariner is the sole survivor of the ill-fated crew. The bodies of the dead crew members lay around the deck with their eyes staring at the Ancient Mariner. The Ancient Mariner recounts how he felt, how he wanted to die but was not allowed that luxury.

The Ancient Mariner is the sole survivor of the ill-fated crew. The bodies of the dead crew members lay around the deck with their eyes staring at the Ancient Mariner. The Ancient Mariner recounts how he felt, how he wanted to die but was not allowed that luxury.

I looked to Heaven, and tried to pray:

But or ever a prayer had gusht,

A wicked whisper came, and made

my heart as dry as dust.

I closed my lids, and kept them close,

And the balls like pulses beat;

For the sky and the sea, and the sea and the sky

Lay like a load on my weary eye,

And the dead were at my feet.

But the curse liveth for him in the eye of the dead men.

The cold sweat melted from their limbs,

Nor rot nor reek did they:

The look with which they looked on me

Had never passed away.

An orphan’s curse would drag to Hell

A spirit from on high;

But oh! more horrible than that

Is a curse in a dead man’s eye!

Seven days, seven nights, I saw that curse,

And yet I could not die.

I suppose you may curse me, like the curse put on the Ancient Mariner, but I am not going to tell you the end of the story in the hope that you will go out and get yourself a copy of the epic poem, and if possible, a copy with the Gustave Doré’s woodblock illustrations. You won’t regret it.

In 1920, McCarthy moved to New York City and established a studio at East 40th St. in Greenwich Village. It was around this time that her signature on her paintings changed. She began signing her paintings with her mother’s surname “Kiner” as her middle name becoming Helen K. (Kiner) McCarthy.

In 1920, McCarthy moved to New York City and established a studio at East 40th St. in Greenwich Village. It was around this time that her signature on her paintings changed. She began signing her paintings with her mother’s surname “Kiner” as her middle name becoming Helen K. (Kiner) McCarthy.