Last week, I went to the Royal Academy which was staging three very different exhibitions. Each one had its supporters and it was interesting to walk through each and compare the works on display. I know that is somewhat foolhardy as one would never contemplate and compare the athletic prowess of a baseball star with a soccer star or a football star with and ice hockey player. Each has a skill of their own and one cannot make a comparison across different sports so I suppose I should not contrast the works of Allen Jones with Anselm Keifer or Giovanni Moroni. All are so different and it is up to one’s individual taste as to what one believes is the most beautiful and the most eye-catching.

For me, the choice was a no-brainer. I have always liked paintings from the 16th and 17th century and I have always admired the genre of portraiture and so my favourite, by far, was the Giovanni Battista Moroni exhibition which is on at the Sackler Gallery until January 25th. In my next two blogs, I would like to whet your appetite by looking at the life and some of the works of art of one of the greatest Italian portraitists of the sixteenth century and by doing so try and persuade you to visit the wonderful exhibition.

Giovanni Battista Moroni was the son of architect Francesco Moroni and Maddalena di Vitale Brigati. He was born around 1522 in the Venetian Lombardy region of northern Italy, in the commune of Albino, in the province of Bergamo. It was a time close to the end of the Italian Renaissance period which had started back in the fourteenth century. It was an exciting period of cultural change which brought about new styles of art, music, literature, and architecture. This was a time designated as the Cinquecento also known as High Renaissance period and it was during this time that a secular theme started to manifest itself in the subject for paintings. Moroni was apprenticed to Alessandro Bonvicino more commonly known as Il Moretto da Brescia who had a studio in Trento which at the time hosted the great meeting of Catholic clergy at the Council of Trent between 1545 and 1563. For Roman Catholicism, this was It was the most important ecumenical council which had been called to come up with ideas to counter the Protestant Reformation.

In this first blog about Moroni I want to concentrate on his portraiture and I have chosen four of my favourite works from the exhibition. One of his most famous works and considered to be one of the masterpieces of sixteenth century portraiture, is entitled Il Tagliapanni (Portrait of a Tailor), which he completed around 1570. What is mystifying about this portrait is the fact that the title of the work although telling us this is a portrait of an artisan the costume of the man before us would seem to have aristocratic connotations. The setting for the portrait is a bare room, which is not well illuminated and which contrasts with the way Moroni has illuminated the head of the tailor form a light source coming from the left of the painting. The lack of furnishings allows us to concentrate on the subject of the painting. The figure, who stands by his cutting bench, is the tailor. He is wearing doublet and hose. He has a cream fustian jacket and wears full red breeches, which almost, but not quite, hides a similar coloured codpiece. The colour of the clothing worn by the tailor was a change from Moroni’s normal male portraits as he had, as a rule, had his sitters dress in all-black clothing which was the Spanish fashion-style of male sitters. Around his waist is a sword belt – another hint of aristocracy. He looks out at us pensively. Maybe he just considering carefully what he is about to do. He has a pair of scissors in his right hand, on the small finger of which is a gold ring set with a ruby. His left hand spreads out a piece of black cloth which he is about to cut. One can just make out the faint white lines on the cloth which are a guide to the pattern which he is about to cut out. This is not an impoverished tradesman and much speculation has been made as to who is this man. Because of the richness of his clothes, some art historians, like Francesco Rossi in his 1991 book Il Moroni, would have us believe that he was an aristocrat who has turned to selling fabrics. Others believe that not to be the case. However the manner which the tailor is depicted gives one a distinct impression that the tailor was financially secure. In the Grazietta Butazzi a leading authority on the history of fashion an article appeared in the 2005 edition on men’s fashion between fifteenth and seventeenth centuries and they were adamant that the style of costume on Moroni’s tailor was not out of place with his professional status as a tailor and that it was similar to garments seen on prints of the time, which depicted men in his trade.

The next portrait by Moroni, which I am featuring, is of Gian Gerolamo Albani and with it comes an amusing anecdote. Albani was a powerful politician and military man in the Lombardy Veneto region. In 1563 he fell from grace and was exiled for five years on the Adriatic isle of Hvar and banished from Veneto . Gian Gerolamo Albani had had to endure this fall from power following his implication in the murder by Albani’s son of a family member of the rival Brembati family, Achille Brembati. From Hvar Gian Girolamo moved to Rome and in 1570, at the age of sixty-one, was made a cardinal in the Catholic Church by Pope Pius V. Pope Pius V, who was born Antonio Ghislieri, and served his time in the Catholic Church as an inquisitor, was a friend of Gian Battista Albani and it was Albani that had once saved the life of the future pope.

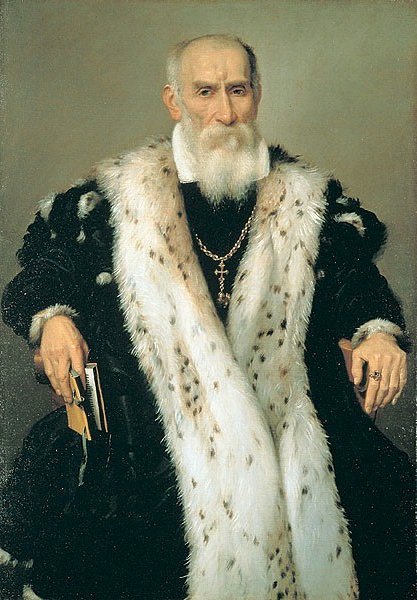

Moroni favoured his sitters to adopt a three-quarter style profile but in this portrait of Albani he sits directly facing the viewer. There is an aura of power about this man before us. He sits upright in a Dantesca chair, book in hand. He wears a luxurious black robe which is lined with lynx fur, which can also be seen appearing from slashes around the shoulders and cuffs. This “slash and puff” fashion style will again be seen in the portrait of his daughter, Lucia. Around his neck, adding an even more prestigious appearance is a gold chain on which hangs the lion of St. Mark, which alludes to Albani being a member of the Knights of the Order of St. Mark, an honorific Order of Chivalry title conferred on him by Andrea Gritti, who was at the time, Doge of the Republic of Venice. The winged Lion passant holding a drawn sword in one paw and an open book with the motto Pax tibi, Marce Evangelista meus (Peace to you, Mark, my Evangelist) in the other. On the reverse there was a portrait of the Doge and St Mark.

And so to the anecdote I mentioned about this portrait. The seventeenth century Italian art biographer and painter, Carlo Ridolfi, wrote about the origin of this portrait in his 1648 book Le Maraviglie dell’arte: ovvero Le vite degli ’illustri pittori veneti, e dello sato, (The Marvels of art: namely The Lives of illustrious Venetian painters, and the state):

“…Gian Geralamo Albani, a gentleman from Bergamo, a member of the Albani family, finding himself in Venice, sought Titian out to have his portrait painted. He was asked from which area he came and let it be known that he was from Bergamo. ‘What’ replied Titian, ‘do you think you will get a better portrait from my hands than you would get in Bergamo from your Moroni? Best leave this work to him, for it will be more valuable and more distinctive than mine’. Sig. Albani then returned to Bergamo and told the story to Moroni who produced this stupendous portrait now belonging to Sig. Giuseppe Albani…”

Whether the story is true or false I will let you decide but Gian Albani must have been already aware of Moroni and his skills as a portraitist as some ten years earlier, Moroni completed a female portrait entitled Portrait of Lucia Albani Avogadro (‘La Dama in Rosso’). She was one of Gian Albani’s daughters. This is an exquisite work and can now be seen at the National Gallery in London. The sitter for this work is Lucia Albani Avogadro an Italian poet. Lucia was one of seven children of Gian Gerolamo Albani, the head of the powerful Albani family of Bergamo. This is not just a painting of a beautiful woman but a depiction of and an insight into of the fashion of the time. Lucia Albani married Faustino Avogadro , her third cousin, when she was sixteen years old. Her husband was a member of the powerful aristocratic family from Brescia.

She is depicted in three quarter profile seated on a Dantesca chair. She wears a glittering red brocade dress with an open bodice which was popular in the 1550’s. The silk was almost certainly given its exquisite colour by the use of the scales of the female cochineal insect from which the carminic acid is derived and which yields shades of red such as crimson and scarlet. Once again we see the fashionable puff and slash style on the dress around the shoulders and upper chest . This fashion style was popular with both men and women. Portraits of Henry VIII often showed him wearing clothes which had the “puff and slash” stylisation. The “puff and slash” effect was achieved by cutting slashes in the garment and pulling puffs of the undergarments through those slashes.

The lady sits upright on the chair. In her left hand is a fan which rests on her lap. She is bedecked with expensive jewellery, including bracelets with agates, a ring on the finger of each hand, both set with precious stones. Around her neck is a single strand of pearls which accompany a set of pearl earrings. Her hair is swept to the back of her head in a most intricate fashion and is held in place by a gold chain with cabochon emeralds. Lucia was not just renowned for her beauty but for her literary skill as a poet but this portrait bears no reference to her literary work, it is simply a depiction of a beautiful lady and alludes to her aristocratic status.

My fourth and final offering of portraiture by Moroni has a connection to the lady in the previous work. The work is entitled Portrait of Faustino Avogadro and is sometimes referred to as The Knight with the Wounded Foot or A Knight with his Jousting Helmet. Giovanni Battista Moroni completed the portrait somewhere between 1555 and 1560 and is currently housed in the National Gallery in London. Avogadro stands in front of an old wall, the base of which is made of marble. There is an element of decay about this backdrop with green vegetation growing out of the cracks in the wall and brown streaks of damp running down across the marble

Faustino is predominately dressed in black. It is a familiar style of the mid 1500’s. He wears a high-collared white shirt and short puffed black pantaloons. Over his shirt we see a torp-coloured jacket and over this, lying open, is a gambeson or arming doublet. This is a padded jacket which was worn as part of protective armour. It could be worn separately, or combined with chain mail or plate armour. The garment was made using a sewing technique known as quilting and was made of linen or wool. In battle, a thrust of the enemy’s sword could penetrate the rings of the chain mail and this often drove the damaged rings deep into the wound. A lightly padded garment, such as the gambeson worn under the chain mail reduced the risk of these types of injuries.

Avogadro’s right hand touches the hilt of his long sword whilst he rests his left arm on his lavishly crested helmet which is adorned with an ostrich feather. Around him are pieces of armour scattered on the floor, the light glinting on the highly polished surface of the steel pieces. Besides this being a portrait of an aristocratic gentleman it is a depiction which is testament to his military rank and his involvement in tournament combat. If one looks closely at his left knee one can see a sort of supporting brace on it which is attached to his left foot. Some art historians believe this contraption was the result of an injury; hence the painting’s “sub-title” The Knight with the Wounded Foot. However, Cecil Gould, a British art historian and curator, who specialised in Renaissance painting and once a Keeper and was at one time Deputy Director of London’s National Gallery, wrote in his 1975 National Gallery Catalogues: The Sixteenth Century Italian Schools that the brace we see in the portrait was more likely to be present to help remedy a congenital defect of the ligaments of the left ankle. One would have thought that such a cumbersome contraption would have put paid to Avogadro’s taking part in tournaments, but apparently not.

Avogadro, like his father-in-law was involved in the deadly feud between the Albani and Brembati families with his servant being sentenced to death for his part in the murder of Count Achille Brembati in 1563. Following this, Avogadro and his wife Lucia Albani fled their Bergamo home and went into exile in Ferrara to escape the aftermath and consequences of the murder. A year later Faustino was dead. It was reported that he fell down a well when he was drunk. Fell or pushed? One will never know for sure. Four years later in 1568, his widow Lucia died, aged 34

In my next blog I will look at some of the religious paintings of Giovanni Battista Moroni.