In May 1816, Christoffer Eckersberg left Rome and headed home to Copenhagen. During his homeward journey he stopped off at Dresden where he met up with the German Romantic painter, Casper David Friedrich. Eckersberg finally arrived back in Copenhagen in August 1816. His reputation as a leading painter of his time was all he could have wished for and soon commissions were rolling in. Probably the most prestigious of these was a commission to paint four large works for the Throne Chamber of the magnificent baroque palace of Christiansborg which showed scenes from the history of the House of Oldenburg. This commission earned him the nomenclature of “court painter”.

(43 x 39cms)

Private collection

One of these works was Duke Adolf declining the offer to be King of Denmark which he completed in 1819. The story behind this event is that in January 1448, King Christopher of Denmark, Sweden and Norway died suddenly and had no natural heirs. His death resulted in the break-up of the union of the three kingdoms, with Denmark and Sweden going their separate ways. Denmark had now to find a successor to the vacant Danish throne and so the Council of the Realm turned to to Duke Adolphus of Schleswig, as he was the most prominent feudal lord of Danish dominions. However Adolphus, who by that time was forty-seven years old and childless, declined the offer but instead supported the candidacy of his sister’s son, the Count Christian of Oldenburg. Christian was elected King Christian I of Denmark and his coronation followed a year later in October 1449. In the painting we see Duke Adolphus declining the offer as he points to the portrait of his nephew, Christian, which is hanging on the wall in the background.

(32 x 28cms)

Museum of National History at Fredericksborg Castle

In October 1817 Eckersberg became a member of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts. This allowed him to apply for any position as professor at the Model School of Charlottenborg, which was the home of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. Whilst Eckersberg had been travelling around Europe he had been funded by a number of patrons and on his return home he decide to repay their generosity by completing portraits of them and their family. One of Eckersberg’s most important and generous benefactors was Mendel Levin Nathanson. He had arrived in Copenhagen aged twelve as a poor Jewish immigrant. Nathanson rose to become a wealthy Danish merchant, editor, and economist who from an early age established himself in business. At the age of twenty-six he became associated with the large Copenhagen banking firm of Meyer & Trier. He was also a leading patron of the arts. He was an author of books on economics as well as the country’s mercantile history but was probably best known for his advocacy of the Jewish cause. Nathanson was editor of the Berlingske Tidende one of the big three national newspapers from 1838 to 1858 and from 1865 to 1866. Eckersberg completed the portrait of Nathanson in 1819.

(126 x 173cms)

Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

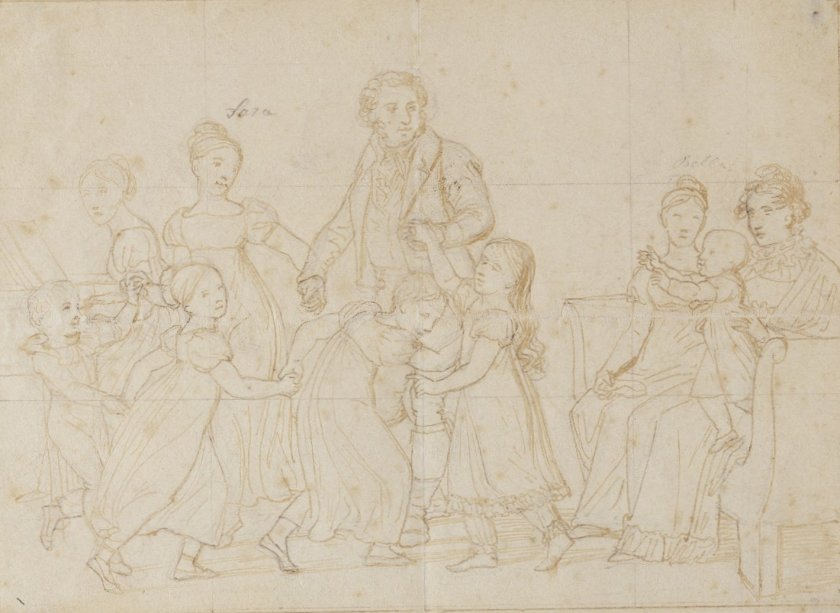

Another of Nathanson’s commissions for Eckersberg was to get the artist to complete a group family portrait, a task he completed in 1818. The depiction was of Nathanson, his wife and their eight children. It was simply entitled The Nathanson Family and the portrait was the most densely peopled and involved work ever attempted by Eckersberg. Nathanson was quite specific about what he wanted the painting to reveal about himself and his family. It was to be a depiction which would tell of his affluence and status in the country.

Eckersberg’s original idea, as seen in a preliminary sketch, was to depict the whole family dancing, highlighting a close and harmonious family connection, a family who enjoyed each other’s company but this idea failed to satisfy Nathanson. For Nathanson the depiction must depict a family of stature and wealth. It was paramount to depict his own prominent position in Danish society as a merchant and an integrated Jew. He again spoke to Eckersberg to remind him how he wanted the family to be depicted. The family members in the finished painting are shown, in a line, blatantly parading themselves before us in a stage-like manner. On the left hand side the depiction focuses on the private life of the children, at play, dancing and one daughter is seen playing the piano. The children’s activity is interrupted by the arrival home of Nathanson and his wife from an audience with the Queen having enjoyed the family tradition of some royal entertainment. There is a sartorial elegance about the velvet-like clothing Nathanson and his wife are wearing and this of course brings home to the viewer of the painting the social and financial class of the couple. The whole scene is a juxtaposition of two visual aspects of Nathanson’s life – the loving husband and father with his happy children and the successful businessman who has access to the Royal Court. In the portrait Nathanson stares out at us inviting us into his house to witness all that belongs to him. His wife stands next to him, somewhat aloof, as the children, who have interrupted their playing to run and greet her.

(125 x 85cms)

Statens Museum for Kunst in Copenhagen

In 1820 Eckersberg completed another portrait for Nathanson. This time it is one depicting his two daughters, Bella and Hanna. For many artists who have been asked to complete a portrait the decision as to how the sitter should be portrayed is a question which has to be carefully answered. Should it be an en face depiction or a profile depiction? In this work Eckersberg has solved the problem by having the daughter, who is standing, portrayed en face whilst the seated daughter is shown in profile. Although it would not be that unusual to see the likeness of the two daughters in this case, could it be that Eckersberg has emphasized the similarities to such a degree that it almost looks as it is the portrait of a single person seen from two different angles. On the table we see a parrot in a cage. Is this just an additional ornamentation which lacks meaning? Actually many believe it is symbolic and that it is all about the two young ladies who are at an age when marriage is on the horizon whilst other believe there is a definite similarity between the shape of the cage and the shape of the girls’ faces

(53 x 43cms)

Danish Museum of Science and Technology, Helsingør

Another of Eckersberg’s interesting portraits is Hans Christian Ørsted which he completed in 1822. It is a medium sized head and shoulder portrait which can now be found at the Danish Museum of Science and Technology in the eastern Danish town of Helsingør. This is a good example of Eckersberg’s ability as a portraitist as to how he precisely and truthfully depicts his sitter. It is a realistically accurate depiction of the man, as confirmed by his wife. The depiction of Ørsted facial expression is one of contemplation which concurs with the views that Ørsted was a great “thinker”. Other than that expression on Ørsted’s face, it disregards the modus operandi of many portrait artists past and present who feel the need to incorporate into the portrait their perceived notion of the sitter’s psychological persona and by doing so they are happy to lose some of the physical accuracy of the person. I know I am in the minority when I say, that for me, a portrait needs to be real and recognisable. I am often told that as I am not an artist I do not understand portraiture !

Hans Christian Ørsted was an acclaimed international scientist born in 1777 who made the discovery that electric currents created magnetic fields which would later be known as Ørsted’s Law. Eckersberg tells us more about the man, not by the way he “adjusts” the portrait but by using the tried and trusted method of including items in the portrait which relate to the man. In his hand we see Ørsted holding a metal Chladni plate on which is sprinkled powder. The powder has now formed a pattern on the surface of it, which is the result of a violin bow, which can be seen on the table in the left foreground, being scraped against the edge of the plate. The catalogue raisoneé of Eckersberg works does not indicate any payment for the portrait and it was probably a gift from Eckersberg to Ørsted as the two endured a long friendship after they had met in Paris years earlier.

(91 x 74cms)

The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts

When Eckersberg stayed in Rome we know he stayed in a lodging house which also accommodated the great Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen and the two became good friends. One of Eckersberg’s most famous and inspired portraits, which he completed in 1814, was of Thorvladsen. It was entitled Portrait of Bertel Thorvaldsen wearing the habit and Insignia of the San Luca Academy. At the time, Thorvaldsen was regarded as the most important sculptor in Rome and in 1804 he became a member of the Florence Academy of Art and a year later a member of the Danish Art Academy. In this portrait, we see Thorvaldsen bedecked in the official robes of the Academia di San Luca in Rome, of which he had been a member since 1808. This prestigious academy was founded in 1577 and as such is among the oldest academies in Europe with its roots being traced to the first statutes written in 1478 for the guild of painters named Compagnia di San Lucca. The robes we see Thorvaldsen wearing provide the portrait with the nuance of an artist who is continuing the work of a long Roman tradition. There is no doubt that the message we can take from the way Eckersberg depicted his friend is the artist’s great admiration for the sculptor and all that he had achieved. Eckersberg, like many admirers of Thorvaldsen, looked upon him as a visionary and the artist has tried to capture that aspect in the sculptor’s contemplative facial expression. Such admiration for Thorvaldsen’s work can be seen by the way Eckersberg has included Thorvaldsen’s most famous piece of sculpture, the Alexander Frieze, which can be seen in the background. Eckersberg was so happy with the finished portrait that he sent it to Denmark as a gift to the Copenhagen Academy. This generous gesture probably had a more ulterior motive, that of proving of his artistic ability to the academicians.

(61 x 50cms)

Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

Eckersberg’s many portraits were not just of male sitters. Portraiture was a great way of making money and many commissions came to him when he returned to Copenhagen. The next painting I am showcasing is The Double Portrait of Count Preben Bille-Braheand his second wife Johanne Caroline neé Falbe which he completed in 1817 and is now housed in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen. Eckersberg had been awarded the Academy’s Gold Medal in 1809 and with it came funds to cover the cost of European travel. However the money did not become available to him until 1812 but he wanted to set off to Paris immediately and so had to turn to some wealthy sponsors to lend him the money he needed to start his journey. One such benefactor was Count Preben Bille-Brahe, a wealthy Danish landowner. On his return to Copenhagen Eckersberg repaid Count Preben Bille-Brahe’s generous support for his European journey by painting a double portrait of the count and his second wife, Double Portrait of Count Preben Billie-Brahe and his Second Wife, Johanne Caroline, neé Falbe. Although their social status was to be part of the aristocracy, Eckersberg has managed a more commonplace depiction of the couple, which he used when he depicted the middle-class in his portraiture, enhancing the view that they were just real people. Having said that, the male sitter with the ruddy cheeks looks resplendent in his brown tailcoat, the buff waistcoat with its lower fastening unbuttoned.

Altarpiece for the Home Church at Funen

Eckersberg had met Count Preben Bille-Brahe in 1810 during the first part of his European journey to Paris. He stopped off at his benefactor’s estate on the island of Funen and received a commission from Count Preben Bille-Brahe to create an altarpiece for the Home Church which was part of the estate. Eckersberg completed the painting for the altar whilst in Paris. It was a biblical scene entitled Jesus and the Little Children.

In my fourth look at the life and work of Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg I will concentrate on some of his female portraiture and his large number of nude paintings.

![View of the Capitoline Hill with the Steps that go to the Church of Santa Maria] d’Aracoeli) by Paranesi (c.1757)](https://mydailyartdisplay.files.wordpress.com/2016/05/view-of-the-capitoline-hill-with-the-steps-that-go-to-the-church-of-santa-maria-d_aracoeli-by-paranesi-c.jpg?w=840&h=632)

Another landscape Eckersberg completed in 1809 featuring the island was entitled The Cliffs of the Island of Møn. View of the Summer Spire. The chalk cliffs on the eastern coast of the island, known as Møns Klint, and the surrounding woodlands and pasture lands has attracted an estimated quarter of a million visitors every year and is the favourite location for artists as it was in the nineteenth century. Christopher von Bülow had his Nordfeld estate near the cliffs so this was probably the reason for Eckersberg depiction. It gave the artist the chance to depict the elements of nature which made the area so loved. The high white limestone peak we see in the background is the Sommerspirit or Summer spire which rises to a height of 102 metres. Unfortunately this natural wonder can no longer be seen as in January 1988 it crashed into the sea due to coastal erosion below its base. Maybe there is a touch of humour in the painting as we Eckersberg depicting a petrified woman shrink back from the edge of the cliff in fear, despite the soothing overtones from her male companion.

Another landscape Eckersberg completed in 1809 featuring the island was entitled The Cliffs of the Island of Møn. View of the Summer Spire. The chalk cliffs on the eastern coast of the island, known as Møns Klint, and the surrounding woodlands and pasture lands has attracted an estimated quarter of a million visitors every year and is the favourite location for artists as it was in the nineteenth century. Christopher von Bülow had his Nordfeld estate near the cliffs so this was probably the reason for Eckersberg depiction. It gave the artist the chance to depict the elements of nature which made the area so loved. The high white limestone peak we see in the background is the Sommerspirit or Summer spire which rises to a height of 102 metres. Unfortunately this natural wonder can no longer be seen as in January 1988 it crashed into the sea due to coastal erosion below its base. Maybe there is a touch of humour in the painting as we Eckersberg depicting a petrified woman shrink back from the edge of the cliff in fear, despite the soothing overtones from her male companion.