Letters of love

“…I love you without knowing how, or when, or from where. I love you simply, without problems or pride: I love you in this way because I do not know any other way of loving but this, in which there is no I or you, so intimate that your hand upon my chest is my hand, so intimate that when I fall asleep your eyes close…”

― Pablo Neruda, 100 Love Sonnets

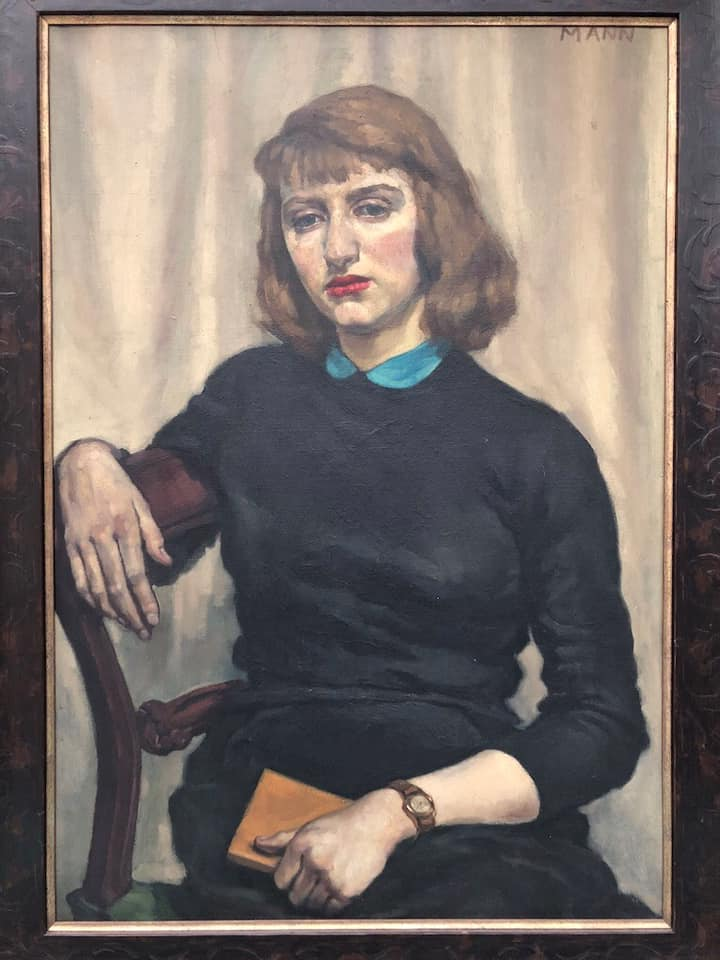

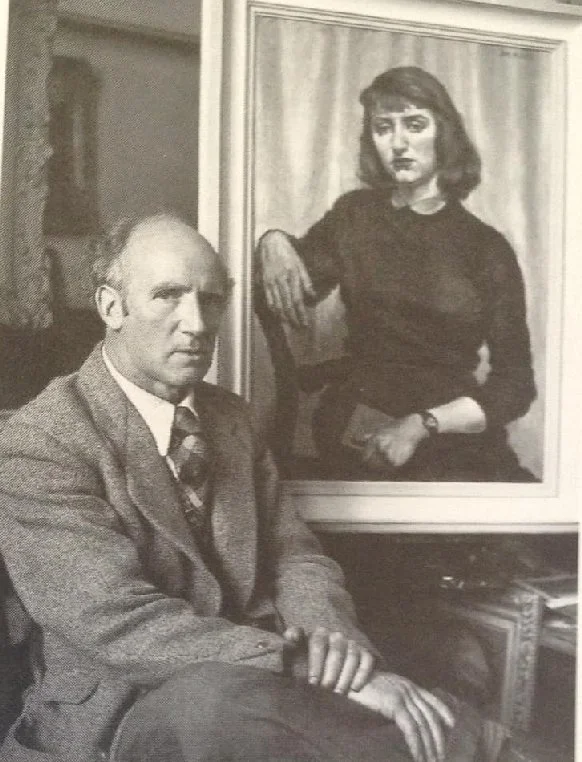

In April 1960, four months after Renske met Cyril, he was admitted to the Royal Free Hospital to have an operation on his perforated stomach ulcer. Renske wrote Cyril a letter to say that she was missing him and expressing her love for him. Note that even after being with him since January that year she still addressed him as “Mr Mann”.

Dear Mr Mann

How dreadful that I can’t come to see you tonight. You don’t like the evenings in hospital, do you? Well, I don’t like the evenings in Bevin Court. Why? Because 108 Bevin Court is not complete when you are not here. You are so much my man in body and soul that I simply cannot do without you.

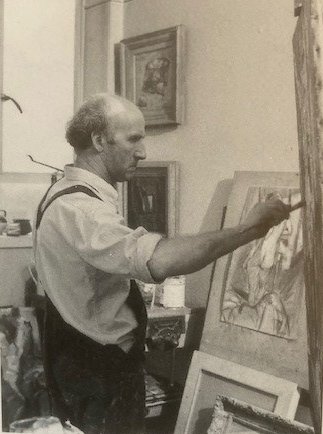

When I am writing to you, and from time to time, I am looking at your paintings, I feel you are so near to me. I love you Mr Mann. I want to tell you over and over again I love you and I pray that i will be your woman for all your life. I realize that I have not much to offer you; no beauty, no money, only my love and I hope one day to prove to you that my love is worth more than beauty or money. You have everything I always wanted: you are an artist, you are my husband, you are my friend, my love, everything. When you leave hospital I will ask for a day off. I will stuff the flat with flowers for you.…..

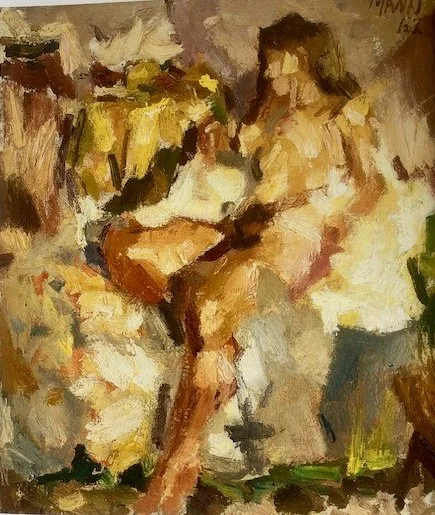

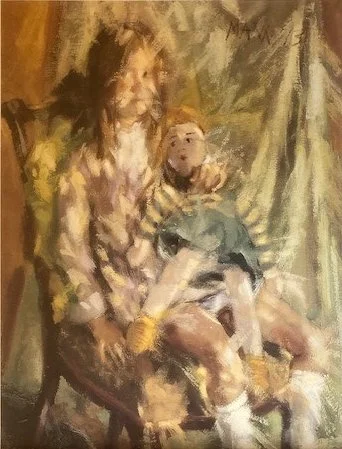

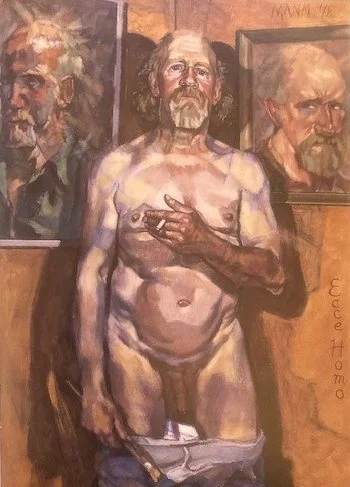

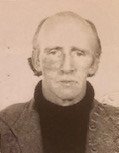

Cyril and Renske (c.1962)

Life in the 60s was all about Cyril and Renske themselves and they were almost oblivious to what was going on around them. They were aware of their limited finances and spending on food was minimal. Cyril cooked and managed the menus. Renske went out to work. If there was a positive to Cyril’s stomach ulcers it was that they prevented him consuming large amounts of alcohol. Once he had recovered from his stomach operation he was once again able to consume alcohol and sadly, after excessive imbibing his mood would often blacken and change to one of being boorish and confrontational. If this alcohol consumption also coincided with his decision to miss taking his anti-psychotic pills then often hell broke loose.

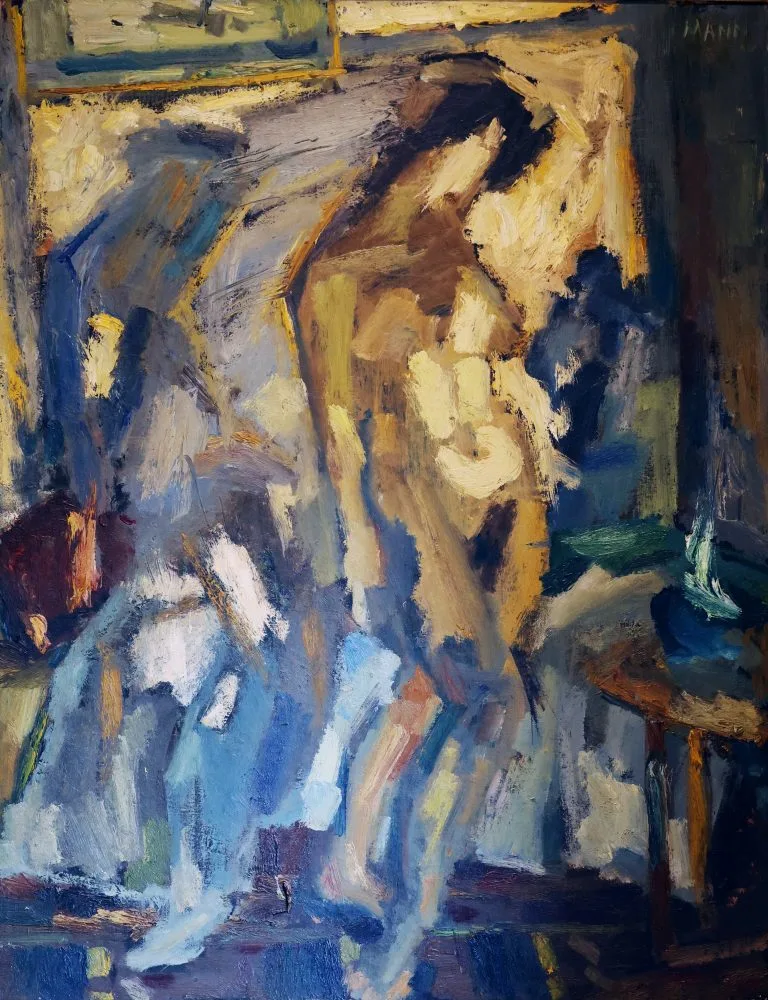

Allotments with Stormy Sky, Walthamstow by Cyril Mann (1967)

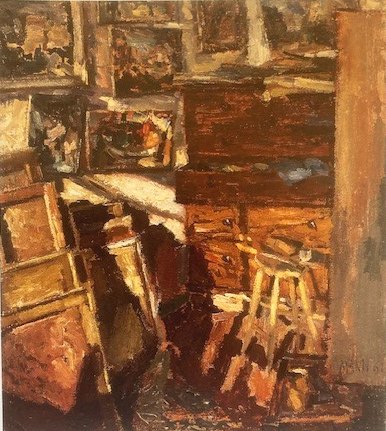

Their small cramped council flat accommodation at 108 Bevin Court was not conducive to painting especially when using large canvases and so, after four years, in 1966, they moved. Renske had always wanted to live in a house and so with great determination and frugality they managed to save enough money for a deposit on a small house at 97 Lynmouth Road in Walthamstow, a town in the London Borough of Waltham Forest, around seven and a half miles (12 km) northeast of Central London. It was a semi-derelict Victorian cottage which cost £2,750.

Cyril and Renske’s home at 97 Lynmouth Road in Walthamstow.

Their savings for the house was boosted by money given to them by Cyril’s long term sponsor, Erica Marx. The house cost £2700 and they had to find a deposit of £700 which was their maximum budget. They struggled to get a mortgage as in those days the income of a wife was not looked upon as viable long-term earnings. However, Cyril was managing to sell his work and had a good credit score and they were finally given a mortgage. Finally, they managed to buy the small house and with it the luxury of having their own small bedroom. The house came with two bedrooms but the larger second bedroom was designated as one were Cyril could store all his painting paraphernalia. Renske said that the fact that we could exit the house into the small garden was something she had previously only dreamed about after having to suffer living in the claustrophobic atmosphere of a top-floor flat in Bevin Court.

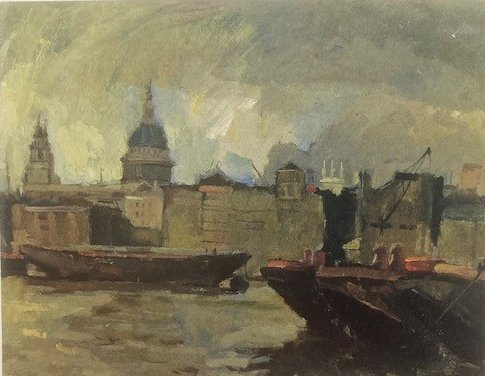

Gas Cooling Towers by Cyril Mann

A new location gave Cyril new opportunities to paint local scenes. Cyril was mesmerised by the massive wooden gas cooling towers which towered above the modern skyline and he would go out in all weather conditions to capture the iconic building.

The Boiling Fowl by Cyril Mann (1963)

One of the first visitors to their Lynmouth Road house was a Canadian actor and TV-game host, Ronan O’Casey and his British actress wife, Louie Ramsey. They had come to see Cyril’s paintings. He fell in love with Cyril’s semi-abstract rendition of a boiling fowl. Renske recounted how they could not believe their luck when he bought it and the couple took it home with them. Cyril liked to recount the story about how months later he and Renske were invited to a dinner party in O’Casey’s smart and chic flat in Hampstead. O’Casey pointed to the painting he had bought from them and hilariously announced that he now has Cyril’s cock on his wall. Renske remembered thinking that it would have been better if O’Casey had purchased one of Cyril’s flower painting !!

Daffodils in a Brown Jug by Cyril Mann (1958)

The problem that arose from the purchase of the Lynmouth Road house in Walthamstow was that it was not quite habitable and so they had to also retain the Bevin Court flat and, so for a time, were paying rent on Bevin Court and a mortgage on the Walthamstow house. Cyril and Renske were given a grant to refurbish their new home and he and one of his ex-students set about renovating the property. They installed a canary-coloured bathroom suite, built units for the kitchen and laid quarry tiles on the floor. Cyril set about the tasks with great gusto and Renske said that her husband’s skills as a carpenter, bricklayer and decorator were amazing. Cyril was a great handyman, like his builder father and grandfather.

Christ Church Spitalfields seen across bombsites from Scrutton St by Cyril Mann

Renske loved her new home as it had a small garden with an apple tree and raspberry canes. To make ends meet, Renske began to work full-time. She had completed twelve months of temping at the advertising agency in their PR department and now became an assistant with a proper permanent job. More importantly, Cyril began to boost her self-confidence and told her that she could achieve anything she put her mind to. Renske basked in Cyril’s confidence in her and deep down began to believe in herself. Although Dutch, she could write in English and began to put together articles on art which she submitted to art magazines and had them accepted. Soon she was getting paid for her submissions. This was indeed a happy time in Renske’s life. Cyril continued to stay at home and paint whilst Renske went out to work. He always had a meal waiting for her after she returned home from work.

Sunlit Daffodils in a Blue Jug by Cyril Mann (1966)

On November 5th 1968 Amanda Mann was born. She was Cyril Mann’s second child but the first born to Renske. Cyril had been faithful to the promise he made to Renske that he would give her a baby whenever she felt the time was right. The decision to have the baby was a maternal versus financial one as Renske knew that as the breadwinner it would mean a great financial sacrifice even though their finances had improved. For Cyril it would also be a sacrifice as he was fifty-seven years old and had already brought up one child, Sylvia.

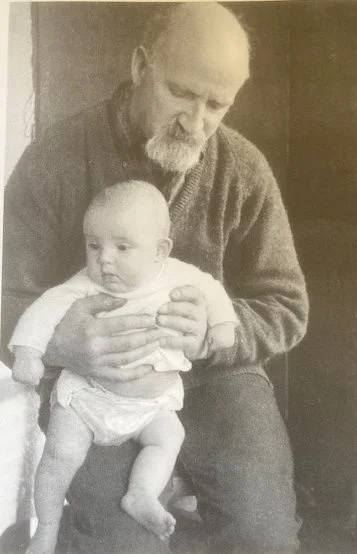

Baby Amanda

However once Amanda was born, she was lavished with kindness and love by both her mother and father. Cyril would walk the streets of Walthamstow and the local market with baby Amanda in her second-hand pram, all the time being admired by the stallholders. Renske recalled that once when he returned home with Amanda, on lifting her out of her pram, he found a hoard of silver coins which the stallholders had surreptitiously slid under the blankets of the pram. They later told Cyril that it was lucky to touch a baby’s head with silver. Cyril could not believe such generosity existed and was moved to tears. Having just given birth to their baby, Renske had very little bed rest as there was no such thing as maternity leave in those days and so for financial reasons, she had to return to work.

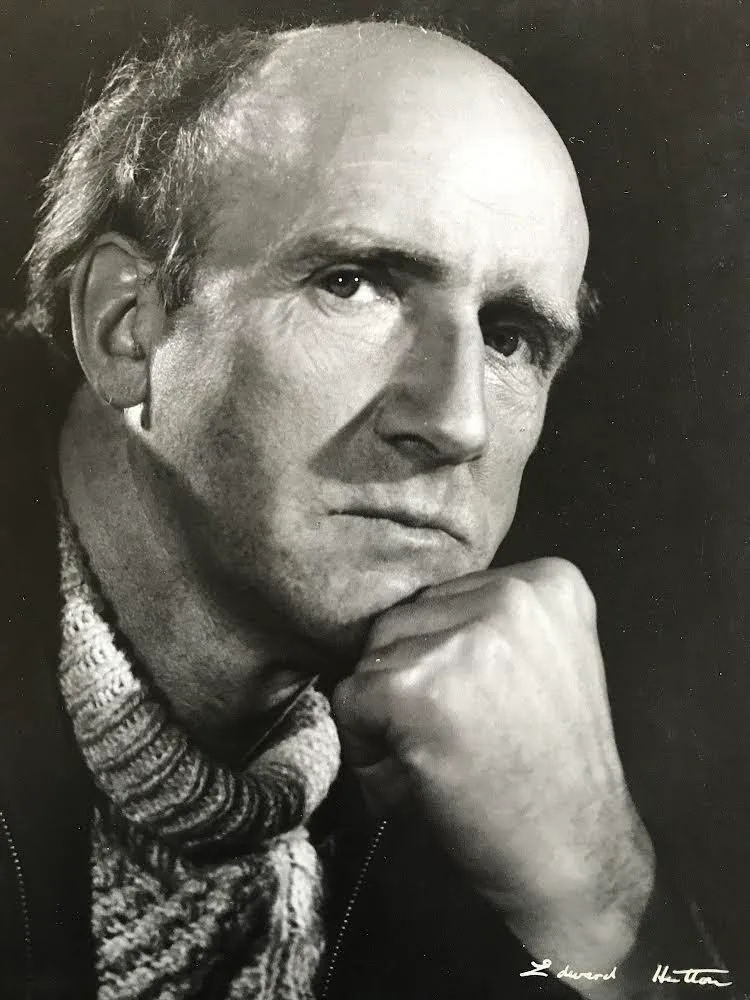

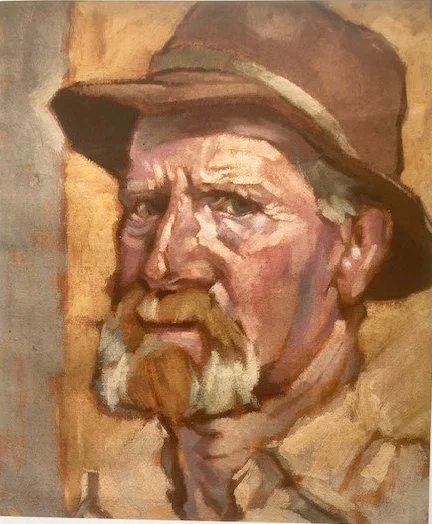

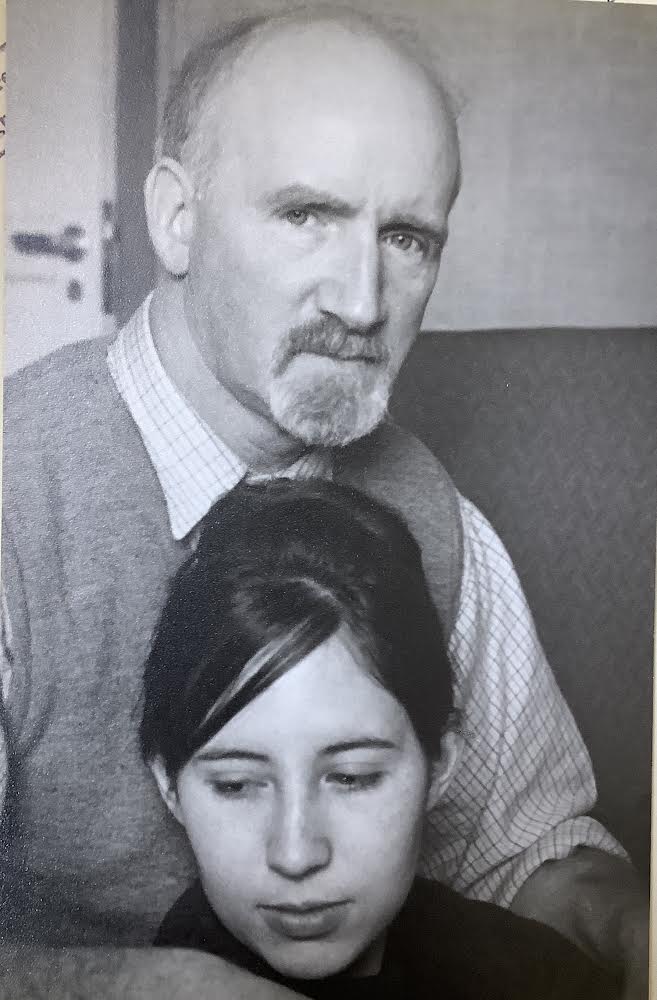

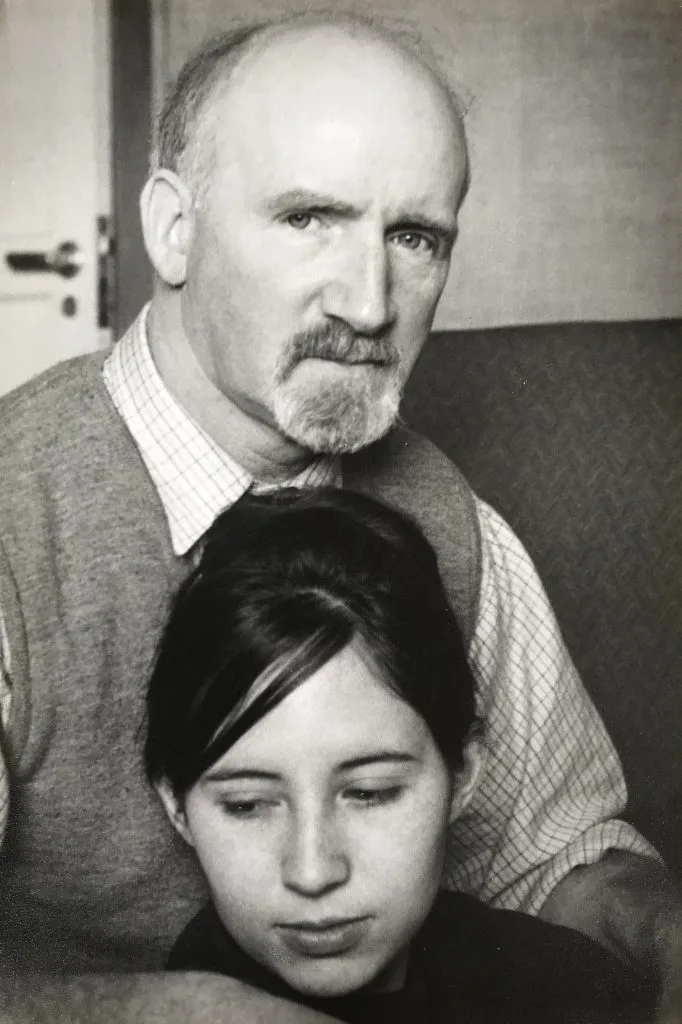

Cyril Mann with his daughter, Amanda.

Although the Walthamstow house was much roomier than Bevin Court it still just had one large bedroom and one small bedroom and Cyril had taken over the larger one for his art studio, leaving him and Renske to sleep in the smaller bedroom while Amanda slept on the landing in her pram. Renske’s career in PR had rapidly progressed and she was beginning to earn a substantial wage and this upward turn in the family finances meant that late in 1969, Cyril, Renske and one-year-old Amanda moved a few miles down the road from their Walthamstow house and went to live in their newly purchased house in Leyton.

Trolley Bus, Finsbury Park by Cyril Mann (c.1948)

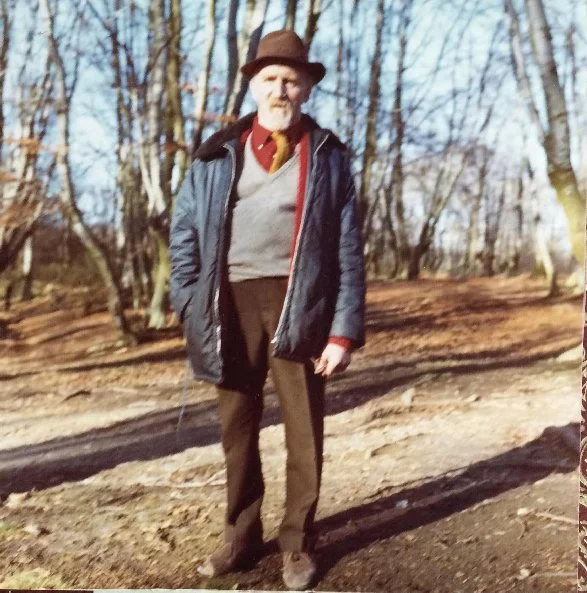

This new residence at 23 Goldsmith Road, Leyton was a five-bedroom house with a 100ft garden and had all the studio space Cyril could dream of. Cyril would spend hours walking through the nearby Walthamstow Forest.

Walking through the forest

It was coming up to Cyril and Renske’s twentieth anniversary of their first meeting but relations between them had reached an all-time low. Eventually things between Cyril and Renske got to a point when she could no longer bear the sadness of this total breakdown of their relationship and she knew she had to leave him. Amanda, who was eleven years old had been safeguarded from this parental breakdown as she was at boarding school in Eastbourne having achieved an open scholarship.

Tubby Isaacs Shellfish Stall by Cyril Mann (c.1955)

One night in early December 1979, after a particularly heated and nasty argument Renske became physically scared of Cyril and made the momentous decision to leave him and, whilst he slept, she slipped out of the house and away, like his first wife, Mary had done some twenty-nine years earlier. Renske went to stay with friends, who were horrified to see Renske in such a fragile mental and physical state. She returned to Cyril for a visit just before Christmas but knew she would not remain with him. She was shocked to see how he had deteriorated both physically and mentally. At the short meeting she promised Cyril that she would continue to support him financially and that he could see Amanda whenever he wanted, providing his mental state was conducive to such a father/young daughter meeting. He pleaded with Renske to stay with him and was devastated when she refused.

Roses with Books by Cyril Mann (c.1971)

Renske along with Amanda travelled to the Netherlands to see her parents and returned early in the New Year. On arriving back in London, Renske contacted one of Cyril’s neighbours in Leyton to find out how he was coping. She was told that he had suffered a second and more serious heart attack and had been rushed to the local Whipps Cross hospital where he had been lying in a week-long coma. Renske rushed to his bedside but he was still unconscious. She held his hand as he took his last breath and quietly passed away peacefully, aged 68. It was January 7th 1980, almost twenty years to the day that the middle-aged English artist met the beautiful young Dutch East Indies woman.

Railway Bridge over the Culvert, Walthamstow by Cyril Mann (c.1967)

I have spent many many hours putting together these five blogs on Cyril and Renske Mann. It has not simply been a look at the many paintings Cyril Mann completed during his lifetime. It has been a long literary voyage looking at the lives of the middle-aged English painter and the beautiful young woman who remarkably dedicated her life to him. It was not smooth sailing for either of them and I found myself wondering how they remained together for so long. Why did Renske put up with a man who on many occasions had treated her badly. How did she manage to live with this middle-aged man who had suffered mentally for most of his life? What made her fall passionately in love with an irritable, short-tempered impecunious artist who was thirty years her senior? So many questions.

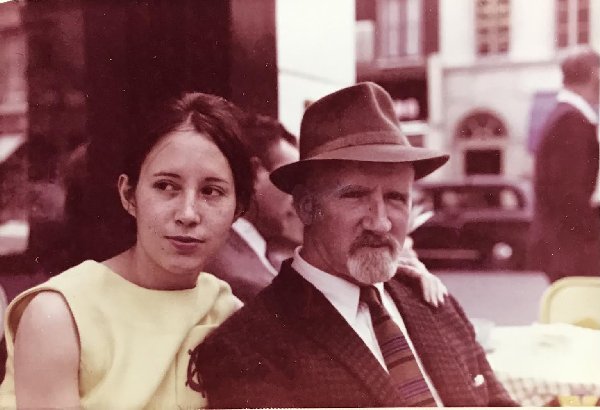

Cyril and Renske during a visit to her family in Dordrecht. Her mother, Nina van Slooten on the far left along with an uncle and aunt.

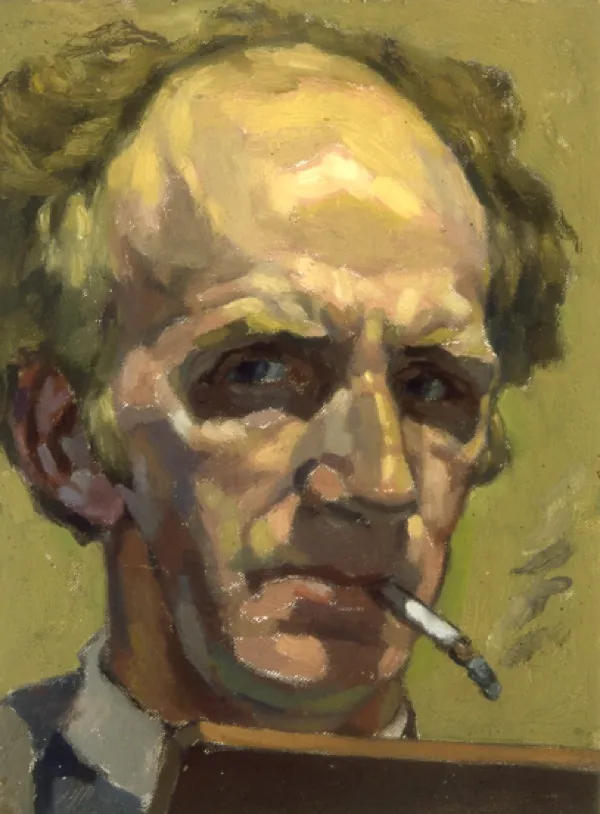

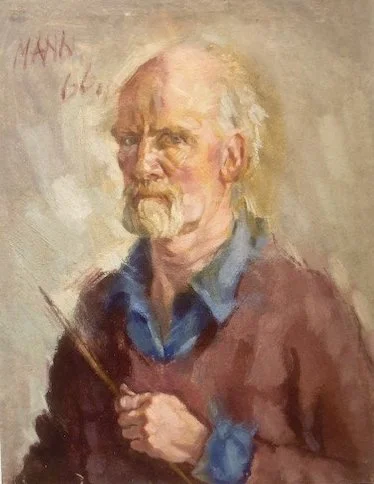

Another question is why did Cyril continually crave recognition for his art and yet abuse those who could have given him such acknowledgement? One of Cyril Mann’s favourite artists was Vincent van Gogh and he drew parallels with his life with that of the Dutch painter. Both had great belief in their art, both in a way believed their skill as a painter was at genius level. Neither received recognition during their lifetimes and both were embittered at their treatment. As years passed and without the recognition, he believed he deserved, Cyril became unstable, frequently volatile and increasingly disillusioned by the unpardonable mistreatment he received from the artistic world.

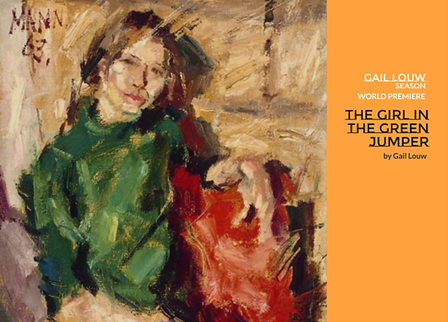

Renske, who is alive and well, knows the answers to these conundrums and maybe she lets us into the secrets in her book, Girl in the Green Jumper, which I urge you to read. What struck me most was the comment she made to Cyril at the start of their relationship that she would make him famous. She had seen the talent and beauty of this middle-aged man and in a way, she was confident of her ability to mould him into the man she believed would be successful and with such success he would lead a much happier life. After reading the account of her life, we know that she never quite succeeded in her aim.

Cyril and Renske in the 1960s.

What did Cyril take from his intense relationship with Renske? I think the answer lies in a letter which Renske found in their house in Leyton shortly after his death. Cyril had written:

My Dear Love,

I received your letter this morning and was afraid to open it for I was so filled with foreboding, which was justified on reading its contents. When I saw the word solicitor, I knew my last bit of hope was gone. I am not going to get upset for it won’t do me any good – harm in fact.

This in a way will be my last letter to you. I do love you, Renske (oh Sweetheart) and always shall. You can cease to love but you will never get rid of mine. In all my pictures the evidence is there and will remain for people to see and realize. You have been a dear and wonderful wife, giving me all and putting me first always. I have been aware of it and have never taken it for granted. Thank you for everything and all the happiness that went with it. I shall always been grateful. I am not bitter or angry even though you have truly broken my heart.

Every day I realize more the reason for taking the step you have. It couldn’t have been easy of you but I now see that it was necessary and that you were really unhappy at home with me and had to take the final step. So, love, don’t please feel guilty or self-reproachful for there is no need. In all things I want is for you to be happy and to realize yourself and live fully. You’ve done your twenty years chores on me. Now think of yourself. You’ve earned it. So I say God Bless, take care of yourself. Remember my heart and any help you may need is yours to call upon at any time…

There can be no doubt that Renske gained a lot of solace from his last words. It gave her the will and the courage to live and continually bring his works to the attention of the public.

Marion Matthews and Renske Mann (September 2022)

Renske, with Cyril’s encouragement, cleared her educational gaps by passing A-levels and then taking an Open University degree. Her PR career blossomed going from strength to strength. She took on the role of director of Scholl, the international footcare-to-footwear company. After Cyril’s death, Renske and her current partner, journalist Marion Mathews, converted a derelict dairy in Holland Park into an art gallery. They operated the venture as a charity, and she and Marion ran the Gallery on a charitable basis for 10 years, until 1993. Their aim was to help unknown, but gifted artists like Cyril so as to reach that first difficult step on the exhibition ladder. Now aged 84, Renske Mann continues to write articles and give talks on her late husband, Cyril, and his paintings, using skills acquired during her time as a PR executive. Her writings on social media attract thousands of followers and admirers.

Renske, you should be very proud of what you achieved.

It would not have been possible for me to put together all five blogs about the artist, Cyril Mann, without information gleaned from a number of sources:

The comprehensive biography of Cyril Mann, The Sun is God by John Russell Taylor

At the presentation of the Islington People’s Green Plaque in September 2013 : Renske Mann,her daughter Amanda next to her along with (far left) Islington Borough Counsellor Catherine West, elected Labour MP in 2015 and on the far right John Russell Taylor, art critic for The Times, who wrote Cyril’s monograph, The Sun is God.

The intimate autobiography of her and Cyril Mann’s life by his second wife Renske, entitled The Girl in the Green Jumper.

This autobiography has now been turned into a play which receives its World Premiere on Wednesday March 13th 2024 at the Playground Theatre, London, 8 Latimer Rd, London W10 6RQ.

Finally, and most importantly I owe many thanks to Renske Mann herself who provided me with information and photographs appertaining to her and her late husband Cyril.

Piano Nobile Gallery London for information and pictures.