This is my last blog relating to Museu Calouste Gulbenkian and the paintings to be found in the Founder’ Collection and I have saved the best till last ! I wanted to take another look at the 19th century collection and choose some of my favourites and explore paintings in other museums which have a connection to those in the Lisbon museum.

Henri Fantin-Latour was a prolific artist and completed many works including a number of portraits. In his 1870 work, The Reading, we have a dual portrait of two women in a domestic setting, both seated and one of them is depicted reading. The theme of reading was the subject of several of his well-known works. The painting is an example of intimism, a French term applied to paintings and drawings of quiet domestic scenes. It is an every-day scene with a sense of sober realism. It also introduces the observer into his favourite themes, poetic and dreamlike domestic environment with vaguely melancholic undertones. The lady on the left is Victoria Dubourg, a fellow painter whom he met at the Louvre whilst she was copying old masters. She became his wife in 1875.

Across from her, on the right of the depiction, is her sister Charlotte Dubourg. Charlotte Dubourg featured in a number of Henri Fantin-Latour’s paintings. This frequent collaboration between artist and muse gave rise to the speculation that Fantin-Latour was fascinated by Charlotte’s mysterious beauty and that there was an unspoken understanding between Fantin-Latour and his sister-in-law, maybe even more!

A similar double portrait in an interior setting can be seen at the St Louis Art Museum. This painting was entitled Two Sisters and Fantin-Latour completed the work in 1859 when he was just twenty-two years old. Once again, we have a depiction of two young women in the intimate setting of their home. This double portrait shows the two younger sisters of the painter; Marie reads on the right while Nathalie embroiders on the left. Once again, the interior painting is comprised of subdued grey and brown tones which is counterbalanced by the colourful yarns on the embroidery table. There is also seems to be a disconnect between the two sisters. Had the artist intentionally depicted it in that way ? Natalie, instead of concentrating on her embroidery, has an unsettled expression on her face. Something is troubling her. It could be that her brother, through his depiction of her expression, is hinting about her depressive illness which would soon confine her to a mental institution for the rest of her life.

The definition of a Vanitas painting is one that contains a single item, but more frequently, collections of symbolic objects, which remind us of the inevitability of death as well as the transience and vanity of earthly achievements and pleasures. For many artists it was a way to encourage the viewer to consider their own mortality and atone for their transgressions. The next painting I am going to talk about is classified as a Vanitas work but does not have the usual skull or fluttering candle which are often associated with the passing of life in such works. What it does have is a large bubble which is being blown by a young boy. It is the fact that as beautiful as the bubble may appear it will soon burst and the beauty will be forgotten. The painting is entitled Boy Blowing Bubble and it was painted by the French artist, Édouard Manet in 1867. It is now in the Calouste Gulbenkian Museum in Lisbon, which acquired it via André Weil in New York November 1943.

In 1850, Manet enrolled at the rue Laval studio of Thomas Couture and remained one of his students for six years. It could have been his tutor’s 1859 painting entitled Soap Bubbles which gave Manet the idea for this painting.

The painting by Manet was one of a series which featured his illegitimate son Léon Koelin-Leenhoff. Suzanne Leenhoff, a Dutch-born pianist, had been employed as a music tutor for Édouard and his younger brothers Eugène and Gustave. Léon Koelin-Leenhoff was born on January 29th, 1852, the son of Suzanne Leenhoff. His birth certificate stated Suzanne as his mother and “Koella” as his father. The man named as Koella has never been traced and it is widely believed that Édouard was the boy’s father whilst some even point the finger at Édouard’s father, Auguste, Suzanne’s employer. Léon Koelin-Leenhoff was baptised in 1855 and became known as Suzanne’s younger brother. Édouard’s father, Auguste, died in 1862 and in October 1863 Suzanne and Édouard married. Léon featured in a number of Manet’s paintings.

In 1861, Manet’s employed Suzanne’s nine year old son, Léon Leenhoff , for his painting Boy Carrying a Sword. He posed in a 17th-century Spanish infant costume, holding a full-sized sword and sword belt. The work can now be found at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Six years later, in 1868, Léon Leenhoff, now sixteen years of age, appeared in Manet’s painting entitled Le déjeuner dans l’atelier (Luncheon in the Studio). In the summer of 1868 Manet travelled to Boulogne-sur-Mer for his summer vacation, where he worked on this painting. Luncheon in the Studio was staged in the dining room of Manet’s rented house. The title of the painting almost hides the fact that it is a portrait of Léon Koélla Leenhoff. Léon is clearly the main character as he stands “centre stage” in the foreground, leaning against the table. The depiction of Leon is quite interesting. Manet has depicted him as the modern type of dandy, whose self-image plays between arrogance and aloneness. Elegantly dressed in a velvet jacket, confident of his superiority, cool with an air of indifference, he stands with his back to the others. He even avoids eye contact with us and so has an air of aloofness. But is that a fair reading of his character? Maybe his blasé expression hides a hint of sadness. Behind him we see an older man smoking, seated at the table enjoying a coffee and a digestif, and a woman preparing to serve hot drinks. At one time they were thought to have been Manet and his wife Suzanne but this assertion has since been overturned and the figures are now thought to have been servants. The painting is awash with still-life depictions, such as the weapons on the armchair on the left, a colourful pot of plants on the table in the background and the table with a plethora of food and tableware. The still-life accoutrements we see before us, in particular the partially peeled lemon and the placement of the knife over the table edge were reminiscent of Dutch still-life works of two centuries earlier. The painting is part of the Neue Pinakothek in Munich.

There were a number of Monet paintings in the Founder’s Collection but one I especially liked was entitled The Break-up of the Ice. France, like most of Europe suffered one of the coldest winters on record in the latter months of 1879. Monet had been living in Vétheuil, a commune on the banks of the Seine, some sixty kilometres from the French capital from 1878 to 1881 along with his wife, Camille Doncieux and their two sons, Jean and Michel. They also shared their house with their friends, the Hoschedé family. During that period Monet completed more than one hundred and fifty paintings of the area. The winter of 1879 was so severe that even Monet found working outdoors almost unbearable. However, in early December, a sudden rise in temperature caused the ice on the Seine to crack. Alice Hoschedé, the wife of Monet’s friends, who along with her children were living in Monet’s house, described the resulting thaw as terrifying, as half the melted snow slid down from the hills onto the village. It was at this time that Monet painted scene after scene as the ice floes broke on the river and one of these works was The Break-up of the Ice, which he completed in 1880. In this grim and dismal landscape we see the thawing of the ice on the River Seine in January 1880.

It is one of a series of eighteen paintings by Monet at this location depicting the severity of the winter. His works were portrayals of the icy beauty of this wintry landscape. These paintings of ice floes chart Monet’s early fascination with capturing the same motif under differing conditions of light and at different times of day. Some, like the Lisbon painting, focused on the ferociousness of the weather and how it can devastate nature as depicted in the fallen trees, while others focused on the beauty of the winter landscape. Monet must have witnessed first-hand the devastation when the frozen Seine river thawed, dislodging large ice floes that inundated the countryside and damaged bridges The finished painting was almost certainly completed in Monet’s studio after having completed a number of plein-air sketches. Look at the simplicity of the depiction of the ice flows using a series of short brushstrokes.

An example of a more peaceful winter landscape at the same spot was also completed in 1880 and was also entitled The Break-up of the Ice and this painting can be found at the University of Michigan Museum of Art. In this painting a sweeping winter river scene opens up from the foreground and sweeps away towards the left. Ice floes dot the river surface and snowy hills frame trees that stand along the riverbank in the middle distance. The palette of this painting is restricted to mauves, blues, greens, and whites.

John Singer Sargent moved from Paris to London in the summer of 1885 as he was struggling to attract patrons, and so he turned to his friends and family for portrait commissions. Singer Sargent may have been introduced to the cousins Robert and Peter Harrison by Alma Strettell as she was a close friend of Sargent and, in 1877, he had illustrated her book, Spanish and Italian Folk Songs. Robert Harrison, a stockbroker and musical connoisseur had married Helen Smith, a daughter of a wealthy Tyneside businessman and politician and the couple went to live Shiplake Court, in the affluent London district of Henley-on-Thames. The Harrisons, like many of Sargent’s patrons, formed part of the high society of late Victorian Britain. Amongst the Gulbenkian’s Founder’s Collection there was an 1887 painting by John Singer Sargent entitled Lady and Child Asleep in a Punt under the Willows. In the summer of 1887 Sargent was invited by his friends Robert and Helen Harrison to spend the season at Shiplake Court. In the painting we see the sleepy figures of Helen Harrison and her son Cecil lying in a punt, under the shade of a willow tree. They are being gently lulled by the movement of a barge which had just passed by. This work is Impressionist in style. Sargent’s Impressionist period came about in the late 1880’s. The painting falls into the category dolce far niente which means the sweetness of doing nothing, a pleasant relaxation in carefree idleness which describes many of his works between 1887 and 1889.

Another similar work by Singer Sargent is his 1880 painting entitled A Backwater at Henley which is housed at the Baltimore Museum of Art.

The last painting I am showcasing that hangs in the Founder’s Collection is Les Bretonnes au Pardon (Breton Women at a Pardon). It is a fine example of Naturalism in which subjects were connected with the minutely detailed description of urban and rural life. It was an art form which was very popular in the late 1880’s and this work achieved great success for the artist at the 1889 Salon. When I saw this work, I thought it was by Gaugin but in fact the artist, who painted it in 1887, was the French painter, Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret. It is a beautifully crafted depiction of a rural tradition, but what also fascinated me was, what is or was a Pardon? The depiction is termed ethnographic, meaning it is relating to the scientific description of peoples and cultures with their customs, habits, and mutual differences.

The word “Pardon”, coming from the Latin verb perdonare, to forgive, and is a Breton form of pilgrimage and one of the most traditional expressions of popular Catholicism in Western Brittany. It dates back to the conversion of the country by the Celtic monks, It is a penitential ceremony. A Pardon occurs on the feast of the patron saint of a church or chapel, at which an indulgence is granted. There are five distinct kinds of Pardons in Brittany: St. Yves at Tréguier – the Pardon of the poor; Our Lady of Rumengol – the Pardon of the singers; St. Jean-du-Doigt – the Pardon of fire; St. Ronan – the Pardon of the mountain; and St. Anne de la Palude – the Pardon of the sea and they all occur between Easter and Michaelmas, a period between March and October. Pilgrims arrive at these Breton Pardon ceremonies dressed in their best costumes which is probably why they make ideal subjects for artists. The day is spent in prayer and after a religious service a great procession takes place around the church. The Pardon in Brittany has practically remained unchanged for over two hundred years. The ceremony is not one focused on feasting or revelry but one focused on veneration where young and old connect with God and his saints in prayer. Brittany at the time was a favourite location for artists such as Paul Gaugain,

Léon Augustin Lhermitte, Jules Adolphe Aimé Louis Breton and Émile Bernard who were beguiled by the family rituals of the local peasants.

It is known that Dagnan-Bouveret used photographs he had taken at the ceremony in the Finistère town of Rumengol in 1886 as an aid to his finished works. He also used portraits he had made of some of his models.

Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret completed a number of paintings featuring “The Pardon” one of which, The Pardon in Brittany, which is a truly amazing, almost photrealistic depiction of the ceremony. This painting is housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Before us we see penitents wearing traditional regional dress proceeding with an air of solemnity as they joylessly parade around a church. Some of the pilgrims go barefoot or kneel in an expression of remorse. What is quite interesting is that on the reverse of the canvas were drawings of his wife which the artist later used for the young woman in the foreground. When the picture was shown at the 1887 Salon and the 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle, it was hailed a great success by art critics saying they were astounded by its meticulous details. This is almost certainly down to the artist’s use of photographs to help him with the work.

That was final look at the paintings of the Founder’s Collection at the Museu Calouste Gulbenkian in Lisbon. If we ever have the travel restrictions lifted and you find yourself in the Portugeuse capital make sure you pay this museum a visit. You will not be disappointed.

The Casa de Iberoamérica, House of Ibero-America in Cadiz is located in the 18th-century building on Concepción Arenal Street on the edge of the Old Town of Cadiz. It was once the building that housed the Royal Prison. The foundation stone for the building was laid in 1794 but it was not completed until 1836. The buildings remained a prison until 1966 when it was abandoned. Subsequently, it was decided to use it as a courthouse thus preventing it from becoming a crumbling ruin. In 2006 the building was returned to the City Council, and in January 2011 it became the Casa de Iberoamérica.

The Casa de Iberoamérica, House of Ibero-America in Cadiz is located in the 18th-century building on Concepción Arenal Street on the edge of the Old Town of Cadiz. It was once the building that housed the Royal Prison. The foundation stone for the building was laid in 1794 but it was not completed until 1836. The buildings remained a prison until 1966 when it was abandoned. Subsequently, it was decided to use it as a courthouse thus preventing it from becoming a crumbling ruin. In 2006 the building was returned to the City Council, and in January 2011 it became the Casa de Iberoamérica.

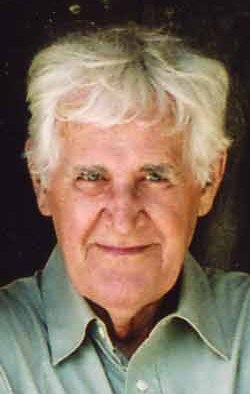

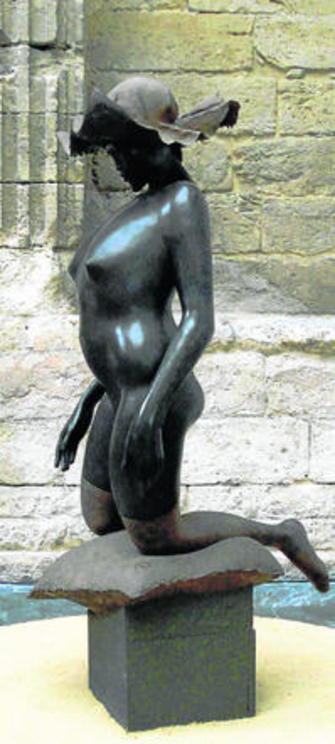

In 1948, Zitman settled in the northern Venezuelan coastal town of Coro, where he found employment as a technical draftsman for a construction company. In that same year, he married a Dutch lady, Vera Roos, whom he had first met in The Netherlands. The couple went on to have three children, Berend, Lourens and Barbara. Much of his free time was spent painting and creating sculptures. Later, in 1949, he moved to the city of Caracas, and the following year, he found work as a furniture designer at a factory of which he later became the manager. In 1951, he was awarded the National Sculpture Prize. In 1955 he was hired by the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism of the Universidad Central de Venezuela to teach courses in decoration, drawing, watercolour and gouache, which was then combined into a design workshop.

In 1948, Zitman settled in the northern Venezuelan coastal town of Coro, where he found employment as a technical draftsman for a construction company. In that same year, he married a Dutch lady, Vera Roos, whom he had first met in The Netherlands. The couple went on to have three children, Berend, Lourens and Barbara. Much of his free time was spent painting and creating sculptures. Later, in 1949, he moved to the city of Caracas, and the following year, he found work as a furniture designer at a factory of which he later became the manager. In 1951, he was awarded the National Sculpture Prize. In 1955 he was hired by the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism of the Universidad Central de Venezuela to teach courses in decoration, drawing, watercolour and gouache, which was then combined into a design workshop. In 1958, he exhibited a collection of drawings and paintings at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Caracas. That year, he decided to give up his life as a businessman and concentrate on his art and sculpture and moved with his family to the island of Grenada, where he dedicated himself completely to painting and began to affirm his style in sculpting.

In 1958, he exhibited a collection of drawings and paintings at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Caracas. That year, he decided to give up his life as a businessman and concentrate on his art and sculpture and moved with his family to the island of Grenada, where he dedicated himself completely to painting and began to affirm his style in sculpting. In 1961 he took part in an exhibition of Gropper Gallery in Boston. He returned to Holland, and studied foundry techniques with Pieter Starrevelt, in Amersfort, and then went back to Caracas where he was given the post as a design professor at the Architecture School of the Central University of Venezuela. In 1964 he converted an old sugar cane mill, known as a trapiche into his residence and workshop, in Caracas’ Hacienda de la Trinidad.

In 1961 he took part in an exhibition of Gropper Gallery in Boston. He returned to Holland, and studied foundry techniques with Pieter Starrevelt, in Amersfort, and then went back to Caracas where he was given the post as a design professor at the Architecture School of the Central University of Venezuela. In 1964 he converted an old sugar cane mill, known as a trapiche into his residence and workshop, in Caracas’ Hacienda de la Trinidad. In 1970, Zitman met Dina Viery, a Russian immigrant, and French art dealer, art collector and one time a model for the French painter and sculptor Astride Maillol whom she met in 1934. Viery was a great friend of Maillol during the last ten years of his life and when he died she helped establish the Musée Maillol art museum in Paris. From then on, Zitman dedicated himself exclusively to sculpture. More exhibitions of his work followed in Venezuela, France, Switzerland, the Netherlands, the United States, Japan and other countries, earning a host of national and international awards.

In 1970, Zitman met Dina Viery, a Russian immigrant, and French art dealer, art collector and one time a model for the French painter and sculptor Astride Maillol whom she met in 1934. Viery was a great friend of Maillol during the last ten years of his life and when he died she helped establish the Musée Maillol art museum in Paris. From then on, Zitman dedicated himself exclusively to sculpture. More exhibitions of his work followed in Venezuela, France, Switzerland, the Netherlands, the United States, Japan and other countries, earning a host of national and international awards. Zitman died on 10 January 2016 at the age of 89. Zitman earned numerous national and international awards for his work and in 2005 he was decorated with the Knight of the Order of the Netherlands Lion.

Zitman died on 10 January 2016 at the age of 89. Zitman earned numerous national and international awards for his work and in 2005 he was decorated with the Knight of the Order of the Netherlands Lion. I will leave you with a recent write-up from the Diario de Cádiz, a Spanish-language newspaper published in Cadiz, regarding the Cornelis Zitman’s permanent exhibition at the Casa de Iberoamérica in Cadiz:

I will leave you with a recent write-up from the Diario de Cádiz, a Spanish-language newspaper published in Cadiz, regarding the Cornelis Zitman’s permanent exhibition at the Casa de Iberoamérica in Cadiz:

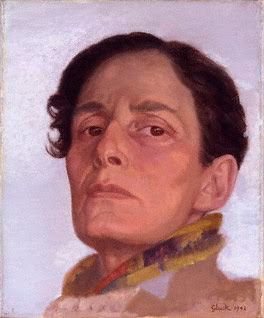

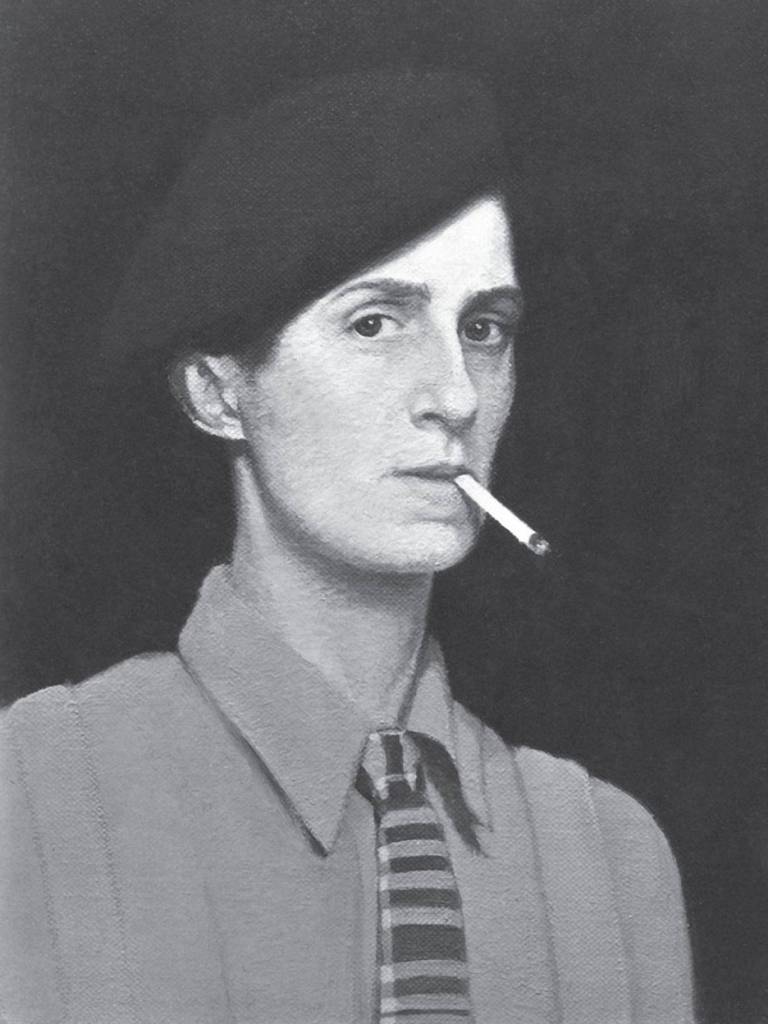

Most of the information for this blog came from the excellent book – Gluck: Her biography by Diana Souhami.

Most of the information for this blog came from the excellent book – Gluck: Her biography by Diana Souhami.