The Sea and the Workers who risk their lives for others.

In this look at Maritime or Marine Art I want to showcase those paintings which feature the people who have dedicated their lives to saving seafarers and those working the seas in a continual search for food to put on our tables.

For the first of my forays into the depiction of fisherman I want to delve into the work of the great Skagen painters. These were a group of Scandinavian artists who had come together in the small coastal village of Skagen, which is situated in the northernmost part of Denmark, from the late 1870s until the turn of the century. One of the Skagen painters was Peder Severin Krøyer. He was born in Stavanger, Norway on July 23rd 1851 but moved to Denmark as a child. At the age of fourteen, he attended the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen. Even at that young age he was a proficient portrait painter and was esteemed for his artwork and received many commissions.

Fishermen hauling nets, North Beach, Skagen by Peder Severin Krøyer (1883)

Krøyer depictions of fishermen were often in more serene situations rather than those showing the fishermen and their boats battling the elements. His painting entitled Fishermen Hauling a Net at the North Beach, Late afternoon, was one of his first works painted on the beaches of Skagen and he wrote to his patron the tobacco manufacturer Heinrich Hirschsprung that for this painting he wanted to be close to the fishermen who had been hauling a net at the North Beach one late afternoon sundown when the sun appears flat and the weather is clear. He had made many small preliminary sketches before taking the large canvas to the beach to complete the work en plein air. He wrote to his patron:

“…I was on Nordstrand for the first time with my large picture this afternoon, driving with all my goods and chattels. It was a huge treat. It was calm and clear, really important for me…”

Fishermen on Skagen Beach by Peder Severin Krøyer (1883)

In his painting, Fishermen on Skagen Beach, several fishermen are shown relaxing on the beach, two of them are catching up on some sleep. The sense of tranquility of this scene is reinforced by a calm sea. This is one of those depictions which invites the viewer to mull over what is going on. Have they had a successful day or had it been a day to forget? Whatever happened they seem to now be exhausted.

Fishermen on the Beach on a Peaceful Summer´s night by Michael Ancher (1881)

Michael Ancher was the first of the Skagen painters to settle in Skagen during the summer of 1881. In his work entitled Fishermen on the Beach on a Peaceful Summer´s night Michael Ancher depicts a group of fishermen from Skagen talking on the beach on a sunny summer evening. What are they chatting about? Perhaps they are exchanging news from Skagen, or simply planning tomorrow’s next fishing expedition. Ancher was a realist who always used living models, preferably fishermen and he knew their individual names and through his depiction they have come to life. They have had a hard life battling the elements which can be seen by their heavily lined faces. This painting which is owned by the National Gallery of Denmark, is currently exhibited in the Danish Parliament.

Fisherman Coming to Shore by Michael Ancher

Michael Ancher has depicted a completely different portrayal of a fisherman than the previous paintings. This is not a relaxed study of a fisherman, quite the opposite. Observe the fiercly determined look on the face of the fisherman in Ancher’s painting entitled Fisherman Coming to Shore. He is trying to steer the boat to the safety of the shore whilst battling against a mighty following sea which makes steering almost impossible.

On the Quay, Newlyn by Walter Langley

Between the Tides by Walter Langley (1901)

Walter Langley, the son of a journeyman tailor, was born on June 8th 1852. At the age of fifteen, he was apprenticed to a lithographer and six years later he won a scholarship to South Kensington School where he studied design for two years. He returned to Birmingham but took up painting full-time, and in 1881 was elected an Associate of the Royal Birmingham Society of Artists (RBSA). In that year, aged twenty-nine, he received a £500 commission for a year’s work by the Birmingham-based photographer Robert White Thrupp, a wealthy patron, to spend twelve months in the Cornish town of Newlyn, and pictorially record the lives of the fisherfolk. Having been brought up in a poor working-class family environment Langley could empathise with the hardship faced by the fishing community and his paintings often depicted stories of family tragedies and loss of loved ones.

Among the Missing by Walter Langley

Never Morning Wore to Evening but Some Heart Did Break by Walter Langley (1894)

The painting, Never Morning Wore to Evening but Some Heart Did Break, was completed by the English artist Walter Langley in 1894. The painting today, as was the painting before, is about loss. The title of the painting emanates from Canto VI of Tennyson’s poem In Memoriam, which reads:

That loss is common would not make

My own less bitter, rather more:

Too common! Never morning wore

To evening, but some heart did break

The painting, Never morning wore to evening, but some heart did break depicts a young woman being comforted on the quayside at Newlyn harbour by Grace Kelynack, the elderly widow of a Newlyn fisherman.

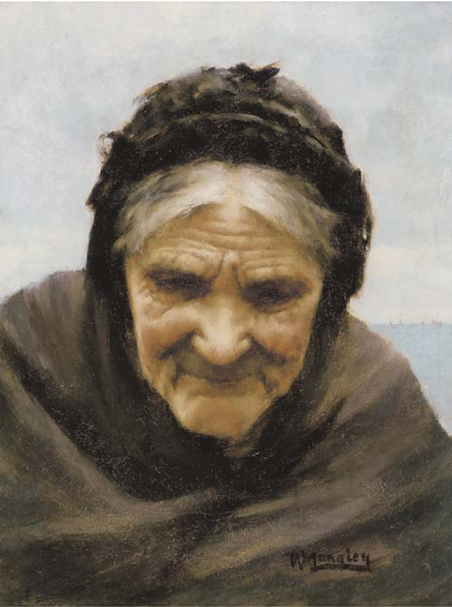

Old Grace by Walter Langley (1894)

Langley had also completed a portrait of Grace Kelynack entitled Old Grace.

The Ninth Wave by Ivan Aivazovsky (1850)

One of my favourite seascape paintings by Aviazovsky is his 1850 work entitled The Ninth Wave. It is also probably his best-known work. The title refers to a popular sailing legend that the ninth wave is the most terrible, powerful, destructive wave that comes after a succession of incrementally larger waves. In his painting, set at night, he depicts a raging sea, which has been whipped up by a storm. In the foreground we see people clinging to the mast of a vessel which had sunk during the night. Note how the artist has depicted the debris the people are clinging to in the shape of a cross and this element can be looked upon as a metaphor for salvation from the earthly sin. One wants to believe that the desperate will to survive will triumph over the raging ocean. The people clinging to the debris are lit by the warmth of breaking sunlight and this gives one to believe that they may yet be saved. For a life-or-death depiction the painting is not a gloomy one. In fact, it is full of light and air and thoroughly transfused by the rays of the sun which endows it with a feeling of optimism. The painting was originally acquired for the State Russian Museum of St Petersburg and was one of the first paintings in the collection of the Emperor Alexander III Russian Museum in 1897.

The Rainbow by Aviazovsky (1873)

Another of Aivazovsky’s works which is part of the Tretyakov Museum collection in Moscow is his painting entitled The Rainbow which features a sailing ship foundering on rocks while two lifeboats full of sailors from the doomed vessel are battling against the fierce seas as they try to manoeuvre their boats ashore. It is a truly remarkable work in which Aviazovsky created a scene of a storm as if seen from inside the raging sea. In the foreground, we see the sailors who have taken to a lifeboat and abandoned their sinking ship which had foundered on the rocky shoreline. They had spent the whole night in the boat. Suddenly they see a rainbow and feel that all is not lost. The reflection of the rainbow can just be seen to the left of the painting. Fyodor Dostoevsky, the Russian novelist, was an admirer of Aivazovsky’s art and The Rainbow was his favourite work. Of the painting, Dostoevsky wrote:

“…This storm by Aivazovsky is fabulous, like all of his storm pictures, and here he is the master who has no competition. In his storms there is the trill, the eternal beauty that startles a spectator in a real-life storm…”

The Shipwreck by J.M.W Turner (c.1805)

Storms and shipwrecks were a popular theme for paintings during J.M.W.Turner’s life. He completed his painting The Shipwreck around 1805. It depicts fishermen battling the huge waves as they attempt the rescue of an overcrowded lifeboat. In the painting, we see a ship foundering and about to capsize and sink in the dark seas. Turner was fascinated by this dramatic theme which conveyed the danger of life at sea. To get us to better appreciate the peril the seafarers had to endure he places us close to the drama and with no sight of land it is as if we are part of the rescuing crews as they battle the ferocity of the sea,

It is thought that Turner was inspired by the re-publication in 1804 of the fourth edition of William Falconer’s poem, The Shipwreck, which was illustrated by another marine painter Nicholas Pocock, part of which (3rd Canto, lines 640-645) is below:

Again she plunges! Hark! A second shock

Tears her strong bottom on the marble rock!

Down on the vale of death, with dismal cries,

The fated victims shuddering roll their eyes,

In wild despair; while yet another stroke,

With deep convulsion, rends the solid oak.

The fourth edition of William Falconer’s The Shipwreck was published in 1772. This poem in three cantos of more than 900 lines each, recounts the final voyage of the merchant ship Britannia and her crew. This fourth edition of The Shipwreck is the first edition of the poem to be published after Falconer’s death, ironically due to a shipwreck. Falconer had been appointed purser onboard the frigate Aurora in 1769 when it was lost after rounding the Cape of Good Hope. An introduction to a 1798 edition of Falconer’s works supposes the loss was caused by the Aurora catching fire after rounding the Cape.

The Storm on the Sea of Galilee by Rembrandt (1633)

A marine painting with a biblical connotation is the one by Rembrandt von Rijn entitled The Storm on the Sea of Galilee which he completed in 1633. It was one of his earliest large format works. It depicts a close-up view of Christ’s disciples as they grapple to gain control of their fishing boat. A large wave has crashed into the side of the boat, swamped the deck and ripped the mainsail. The vessel lurches dramatically in the rough sea. We see one of the disciples leaning over the side of the boat being sick. A man faces us as he clings hold of the rigging. This is a self-portrait of the artist. All the people on board the vessel are panic-stricken, except for one, Christ, who can be seen on the right, calmly looking ahead. The depiction is based on a passage from the bible (Luke 8: 22-25):

22 One day Jesus said to his disciples, “Let us go over to the other side of the lake.” So they got into a boat and set out. 23 As they sailed, he fell asleep. A squall came down on the lake, so that the boat was being swamped, and they were in great danger.

24 The disciples went and woke him, saying, “Master, Master, we’re going to drown!”

He got up and rebuked the wind and the raging waters; the storm subsided, and all was calm. 25 “Where is your faith?” he asked his disciples.

In fear and amazement they asked one another, “Who is this? He commands even the winds and the water, and they obey him.

In the third and final part of these blogs featuring marine art I will be looking at paintings that extoll the joys of the sea and shoreline.

The sheer size of this work, 304 x 505cms (119 x 199 in) is breathtaking.

The sheer size of this work, 304 x 505cms (119 x 199 in) is breathtaking.