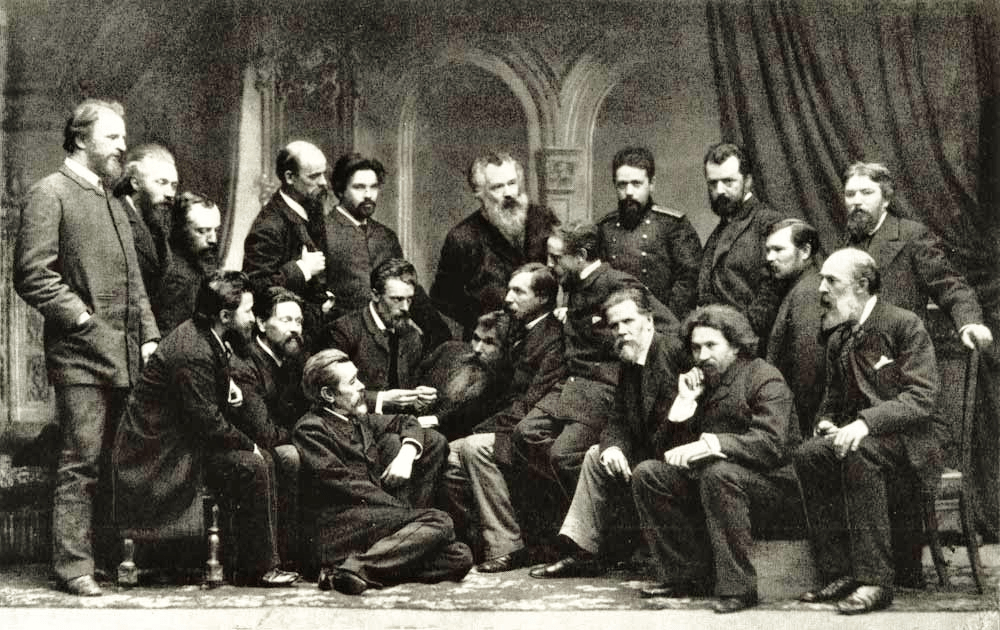

In past blogs about Russian artists I talked about an artistic group known as the Peredvizhniki, often referred to as The Wanderers or The Itinerants and the artist I am looking at today was also a member of this group. The Wanderers gave a voice to Russian art for the first time in the country’s history. Their art answered the people’s search for solutions to their country’s problems. Many of these artists completed works which were parodies of Russian life and were, through their depictions, critical political statements about the Russian ruling class. Russian art critics had voiced their concern with regards the state of Russian art stating that it was devoid of any originality. They wanted artists to focus more on native themes rather than concentrating on what they termed “cosmopolitan garb”.

In 1863 a group of fourteen students, led by Ivan Kramskoi, who were studying at the Imperial Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg found the rules of the Academy too limiting. They also believed their tutors were too conservative and so decided to take a stand. They believed art should be available to all people and, as many could not visit the grand city galleries, they would take their art to the people. They formed Артель художников, the Petersburg Cooperative of Artists (Artel of Artists). The society resolutely maintained independence from Russian state support and took their art, which depicted the contemporary life of the people from Moscow and Saint Petersburg, to the provinces. In 1870, this organization was succeeded by the Peredvizhniki. The Wanderers established a new social artistry that depicted the lower classes and highlighted the issues surrounding social injustices. Of the aims of the Group, Kramskoi believed that their paintings should, as well as being beautiful, be both wise and educational. Among the movements leading members were Ilya Repin, Ivan Shishkin, Konstantin Makovsky, Vasily Perov and Vasily Polenov.

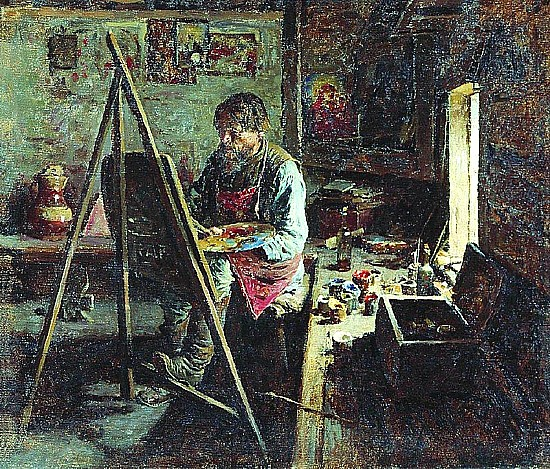

Today’s artist under the spotlight is Abram Yefimovich Arkhipov who was also a member of the group. Abram was born Abram Efimov[ich] Pyrikov on August 15th 1862, the son of Efim Nikitich and Arina Fedorovna Pyrikovs. He was raised in an impoverished household in the small and remote village of Yegorovo, in the Ryazan province, two hundred kilometres south-east of Moscow. He would later adopt the surname “Arkhipov” in honour of his great-grandfather, Arkhip Rodionovich.

Abram showed an interest in art when he was a young boy at the village school. However, the only artistic tuition Abram received whilst at home was from traveling icon painters, one of whom, Zaykov, who had connections with the Moscow School of Painting, which was formed by the 1865 merger of a private art college, established in Moscow in 1832 and the Palace School of Architecture, which had been established in 1749. It was one of the largest educational institutions in Russia. Zaykov was impressed by the Abram’s artistic talent and encouraged him to enter the School. His parents were proud of him and offered him great encouragement to continue with his love art. In 1877, despite being impoverished peasants they managed to collect enough money to send him to study at the School of Art, Sculpture and Architecture in Moscow.

Abram was accepted at the School in 1877 and he studied there for five years. Here he studied alongside future greats in Russian art such as Ryabushkin, Kasatkin and Nesterov and he was tutored by the leading painters of the time, Vasily Perov, Makovsky, Polenov and Savrasov. Arkhipov left the Moscow School and in 1884 transferred to the Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg. Here he was academically successful and some of his paintings were selected for permanent storage at the Academy’s Museum.

Something, however, was not right and Abram broke off his studies at the St Petersburg Academy and in 1887 returned to study at the Moscow School of Art, Sculpture and Architecture . The reason for his sudden departure from St Petersburg is not fully known but it is thought that he was discouraged by the Academy’s strict way of teaching art. However, the reason could have been more mundane, and he simply had no financial means to continue his studies in St Petersburg.

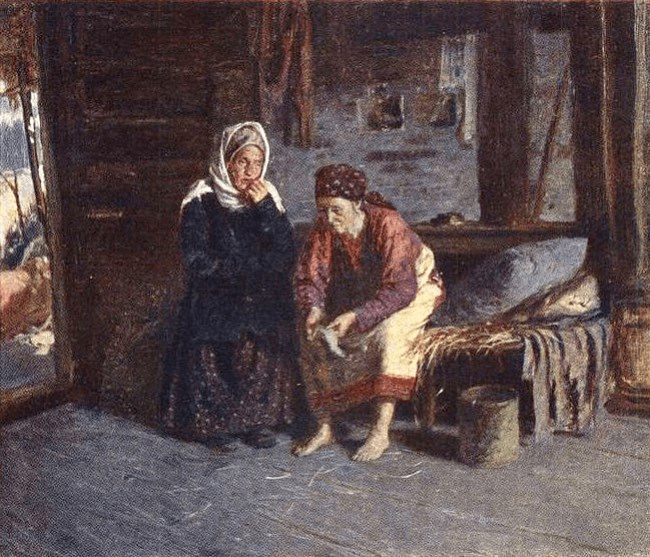

Arkhipov had completed a painting entitled Sick Woman in 1885 and two years later at the Moscow School’s student’s exhibition he exhibited it. It depicts two women in a dark and dank interior. The artist’s mother sits with her head dejectedly inclined, her eyes fixed at one point, Next to her sitting on a straw-filled bed is her neighbour who had come to pay the sick woman a visit. She too has the same dimmed sorrowful look in her eyes The postures of the two women, with their tired, unhappy faces is a depiction of their humility, despondency and misery. The only uplifting aspect to this painting is the sunlight, emanating through the open door. Maybe Arkhipov wanted to remind us that happiness and beauty do exist somewhere. It is a work that gives out both quiet sadness and an air of deep compassion for human suffering. The painting proved to be a major breakthrough in Archipov’s life as the work was bought directly from the student exhibition by Pavel Tretyakov, the art collector and owner of the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow.

Once Abram had completed his studies, he decided to embark on a painting trip with some of his former students, along the River Volga. From this journey he completed a number of paintings like his 1889 work, On the Volga. It proved to be a successful fusion of a genre scene and lyrical landscape.

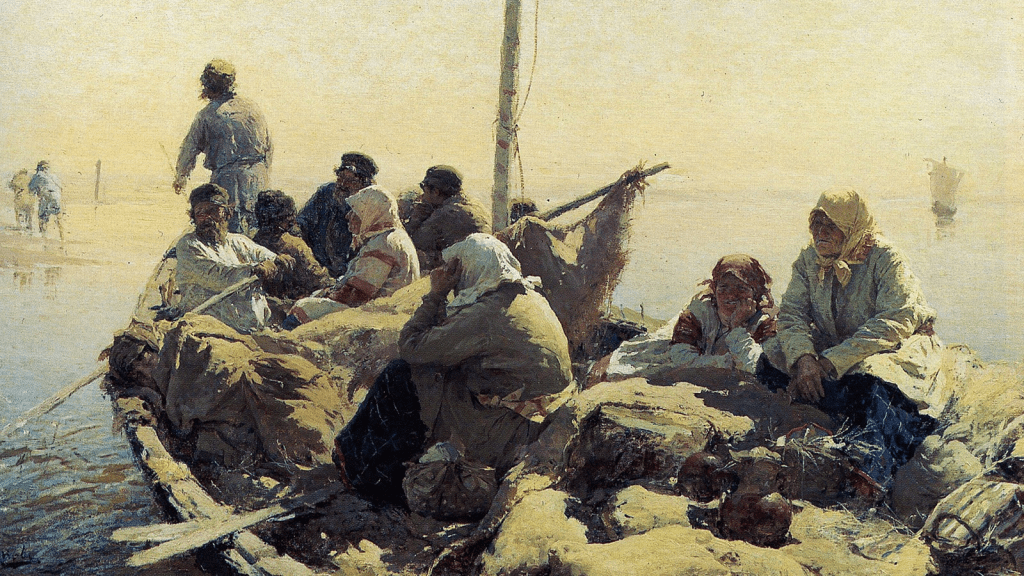

A similar river scene which Arkhipov painted at that time was Along the River Oka. It depicts a barge floating along the river filled with weary peasants, who seem lost in thought. It should not just be taken on face value as a river scene as it is a story about impoverished people who are capable of enduring a great deal without losing their strength and resoluteness. It is both a declaration of the beauty of Russian nature, with its blue horizons, the spring flooding of its rivers, and its streams of sunlight. Arkhipov has used a subdued colour scheme which is in accord with the general mood of the painting. His artistic style has changed. Compared to the careful detail of his early works, his style has become more free, expansive and passionate. Of the painting, the Russian art critic Vladamir Stasov wrote:

“…The whole picture is painted in sunlight and this can be felt in every patch of light and shade, and in the overall wonderful impressions among the people on the barge, the four women—idle, tired, despondent, sitting in silence on their bundles—are portrayed with magnificent realism…”

The work earned Arkhipov membership of the Society for Traveling Art Exhibitions in 1890. He was now one of the Peredvizhniki. It was the largest art association of the second half of the nineteenth century and their exhibitions were held in Russian cities such as Riga, Kiev, Kharkov, and Odessa. Its objectives was three-fold:

Delivery to the inhabitants of the provinces the possibility of contacts with Russian art

Development and love of the arts in society

Making it easier for artists to sell their works.

Many of Arkhipov’s paintings were juxtapositions of landscape and genre works such as his 1892 painting entitled Radonitsa or Waiting for Church in which we see a large group of peasants sitting on the floor outside a church waiting for the doors to open and the service begin, but this is not just any service, this is Radonitsa. Radonitsa is a universal church day when relatives and friends of the deceased celebrate the commemoration of those who have died. In the Russian Orthodox Church it is this commemoration of the departed which is observed on the second Tuesday of Easter. The word derives from the Slavic word radost meaning joy and so it is not looked upon a s a mournful day but one of joyful remembrance. It is the Christian belief that lies behind this joy, is the remembrance of the resurrection of Jesus and the joy and hope it brings to all.

Another of Arkhipov’s paintings which is a mixture of genre and landscape is his 1895 work entitled The Ice is Gone. The painting depicts the connection between nature and the peasants. In a way, it is like the previous work. It is a celebration. The celebration is because the Spring has finally arrived and the ice on the rivers has melted and once more the peasants can use the flowing rivers to their advantage.

Many of Arkhipov’s paintings depicted the harsh plight of female peasant workers and their brutal working environment. One such work was his 1896 painting entitled Women Labourers at the Iron Foundry in which we see two women sitting outside the foundry in the relentless hot sun, trying to relax from their physical labour. Black smoke rises against a backdrop of low, wooden workshops.

The plight of the female worker was again highlighted in two paintings by Akhipov entitled Washer Women which he completed 1899. One hangs in the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow and one in the State Russian Museum in St Petersburg. They were based on a series of studies Abram made of life in the wash-house and are depicted in the muted colours associated with Realism paintings. We see the bent backs of prematurely aged women, toiling amid the steam and heat of their workplace.

In one work he depicts many peasant women working to clean the village’s laundry. For an accurate portrayal, Abram visited many washhouses making sketches always keen to find figures which would enhance his final work. Eventually he found his “perfect” model and rearranged the depiction around her. She was an elderly woman whom we see on the left of the second work, sitting hunched over, totally exhausted. All the women look defeated and overcome by their physical efforts. These two works by Arkhipov’s highlight the plight of woman who had to work in such harsh, almost inhuman conditions just to earn some money to feed their families. Again, like his other Reailist paintings he has used muted colours, the works only lit up by the light coming in from the small window at the rear, which shows up the steam coming up from under their hands as they wash the clothing. Many of the details stay the same in both works, for example, their hair being tightly tied back and the same women appearing in the background of both paintings. The women are all hard at work in the upper painting, whereas the lower work focuses on the elderly woman talking a break.

Arkhipov’s paintings are brutally realistic and are important pieces in history revealing much about the conditions in the USSR during this time by showing the truth behind the closed doors of the washhouses. The opportunity for women to get better and less arduous jobs was just not available to them.

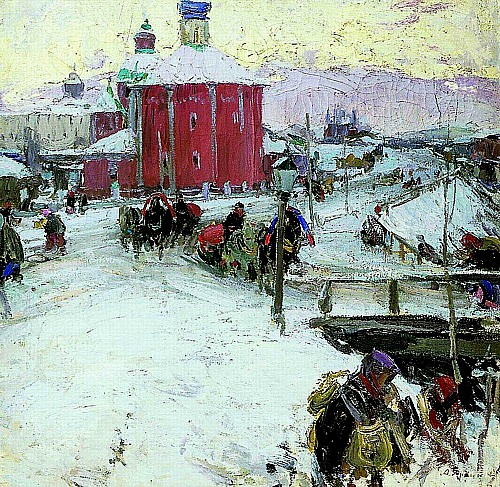

In 1902 Arkhipov took the first of a number of trips to the White Sea and from the sketches he made during these journeys he produced two memorable landscape works. A Northern Village in 1902 and In the North in 1903. They signalled a move away from Realism works and a move towards the landscape genre of paintings.

Around 1903 came the formation of the Union of Russian Artists which was the coming together of former Peredvizhniki members and those who had been part of the World of Art, an artistic movement inspired by an art magazine which served as its manifesto de facto, which was a major influence on the Russians who helped revolutionize European art during the first decade of the 20th century. Arkhipov became one of its founding member in 1903.

Around 1903 came the formation of the Union of Russian Artists which was the coming together of former Peredvizhniki members and those who had been part of the World of Art. The Union of Russian Artists lasted until their exhibition in 1910 when due to a split between St. Petersburg and Moscow artists due to harsh words and denouncements of the paintings by various factions. Arkhipov decided that he had had enough of the constant bickering and resigned.

Following his resignation from the group he reverted to his favoured painting style, that of genre painting and the depiction of peasants. However, the muted coloured realist paintings soon gave way to a more colourful Impressionist style as seen by his 1915 work entitled The Visit (also known as On a Visit; A Festive Spring Day)

Another highly colourful painting was his 1919 work entitled The Tea Party.

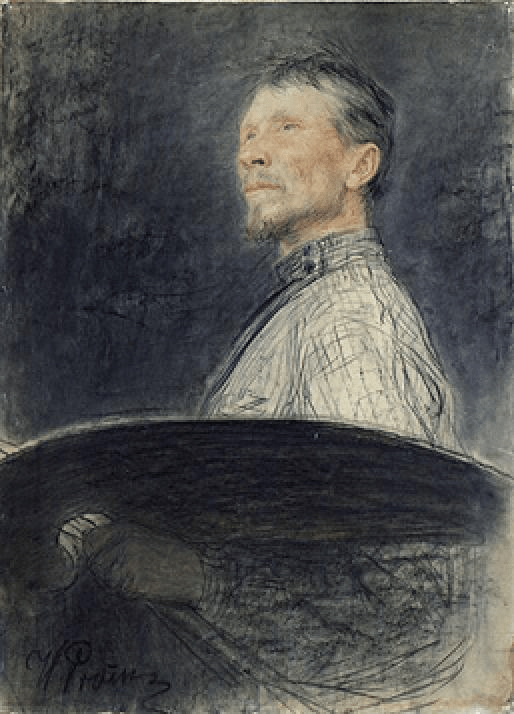

Around 1920, Arkhipov became interested in the genre of psychological portraiture. Psychological portraiture is when an artist tries for something more than a simple physical representation of the sitter but tries to reflectand depice the character of the portrayed person. In essence the painter is endeavouring to capture a range of the sitter’s emotions in fractions of a second or for the finished work to tell us more about the personality of the person in a single image.

Arkhipov painted an unusual series of portraits of peasant women and girls from the Ryazan and Nizhny Novgorod regions. They are all dressed in bright national costumes. with embroidered scarves and beads. Painted with broad lively strokes, the paintings are marked by their decorative nature and buoyant colours, with rich reds and pinks predominating. The most famous of his portraits is his 1927 painting entitled Girl with a Jug. It depicts a Russian woman dressed in an orange top, a bright red bottom, an apron with a bright pattern. In her hands she holds a bright blue cup and a jug of milk. The dark background, painted by the artist, sets off the girl. Her figure is hidden from us by the wide sleeves and a skirt. She smiles confidently as she looks out at us with an affectionate countenance. The painting is a mass of colour and yet Arkhipov seems to also focus on the inner beauty of the woman which he believes is a window into the Russian soul, strong and yet truthful, open-minded, and generous. In this colourful cycle of painting female peasants, Arkhipov has loosened the shackles of his gloomy realist depictions and his shown us a different side to his art.

In 1924 Arkhipov joined the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia, and in 1927, to mark his fortieth year as an artist, he was among the first artist who was awarded the title of *People’s Artist of the Russian Republic*.

Abram Yefimovich Arkhipov died in Moscow on September 25th, 1930 aged 68.