In 1958, Remedios Varo participated in the First Salon of Women’s Art at the Galerías Excelsior of Mexico, together with Leonora Carrington, Alice Rahon, Bridget Bate Tichenor and other contemporary women painters of her era. Remedios submitted two of her works, Harmony and Be Brief, and won the first prize of 3,000 pesos.

In 1958, Remedios Varo participated in the First Salon of Women’s Art at the Galerías Excelsior of Mexico, together with Leonora Carrington, Alice Rahon, Bridget Bate Tichenor and other contemporary women painters of her era. Remedios submitted two of her works, Harmony and Be Brief, and won the first prize of 3,000 pesos.

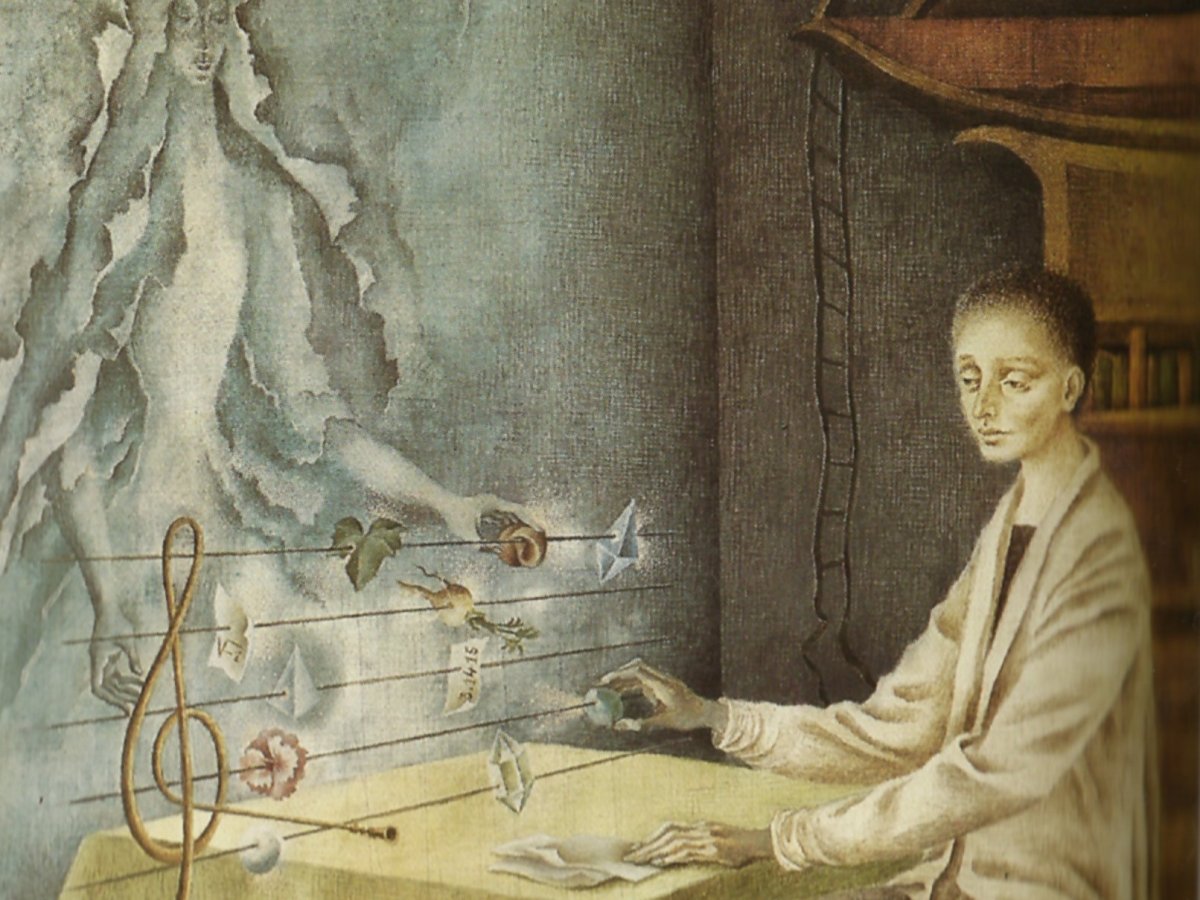

Her painting Harmony is a fascinating work of art. According to Luis-Martín Lozano an art historian and curator of modern and contemporary art:

“…Harmony was conceived as a self-portrait, where the author takes on the role of the organizer of the universe, using a sheet music mill to connect with creatures from other dimensions through magical crystals and formulas…”

In the painting, sitting in a medieval study, we see an androgynous figure of a scientist although some believe it to be a self-portrait of the artist. The figure takes objects from a treasure chest such as geometric solids, jewels, plants, crystals, even a scrap of paper with the mathematical constant, pi, written out to six digits.

They are then placed as notes onto a three-dimensional musical staff, which is being used as an arranging tool, and by doing so, creates from a chaos of possibilities, the order that is music. On the wall behind the staff we see a female figure who also adds items to the strings of the musical staff. This is the hand of chance, which is a vital ingredient in attaining scientific achievement.

The depiction has been likened to the Renaissance painting by Antonello da Messina’s work entitled Saint Jerome in his Study, which he completed around 1475. In both paintings a solitary figure sits in a self-contained space surrounded by thick heavy stone walls, arched doorways and ceilings and a multi-design floor.

The trompe l’oeil technique was used by both artists. Antonella attempts to trick the viewers eye with what looks like a three-dimensional step in the foreground of his painting whilst Varo has presented us with a bird’s nest emerging from a split in the back of the upholstered chair. Varo wants not only us to be fooled by this aspect but she shows that a bird is also deceived! Varo’s painting mirrors the Netherlandish style of paintings of the fifteenth and sixteenth century in the way there are so many items within the depiction, each one making you query why it had been inserted. Do the various items have a certain meaning that we should grasp? We should also remember that as a teenager her father would take her to the Prado in Madrid and it was here that she fell in love with the works of Hieronymus Bosch which displayed a myriad of objects, figures and weird details.

Hieronymus Bosch’s famous triptych painting Garden of Earthly Delights which hangs in the Prado could well have been remembered by Remedios when she painted her 1959 work entitled Troubador as both have oversized yet identifiable birds depicted.

Again, in this painting we see a bow being pulled across, not a stringed instrument, but the long strands of hair of a female. In an earlier blog, we saw a painting depicting the bow being drawn across sunbeams.

Another interesting painting by Varo is one entitled The Juggler. At the centre of the depiction we see the magician/juggler standing on a table in front of a crowd of onlookers. The table actually forms part of his bizarre-looking vehicle. The Juggler is dressed in a red robe which covers his brown-patterned outfit and atop his head he wears a witch-like conical hat. The face of the juggler is painted on a five-sided piece of inlaid mother of pearl. Mother of pearl was often associated with works by Remedios Varo. For her, it was the idea of enlightenment and of understanding, a sort of hyper-awareness. The figure is in the act of juggling but instead of using his juggler’s rings which lay at his feet he is juggling balls of light adding to the impression that this is not just an ordinary juggler but one with mystic powers. Look carefully at his audience. All look the same with similar hairstyles and yet on closer inspection they all have individual expressions. However, what is more bizarre are their clothes. Again, on closer inspection their clothes are made from just one single cloak which is worn by them all. It is all about unity. Varo, in a letter, described the audience as:

“… a kind of unenlightened individuals who were awaiting a transference of enlightenment from the magician so that they can wake up…”

The painting does not just depict the juggler and his audience. Look closely at the others in the “cast” that add to the depiction. Varo includes and owl who we see in the part-open chest, a lion that lies obediently at the juggler’s feet and the ever-present birds. Inside the vehicle is the juggler’s wife and a goat. It is this type of painting that I find fascinating. No matter how many times you look at it there is something new to see and it taxes your brain trying to work out what Remedios was thinking when she put brush to masonite. The painting is housed in the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

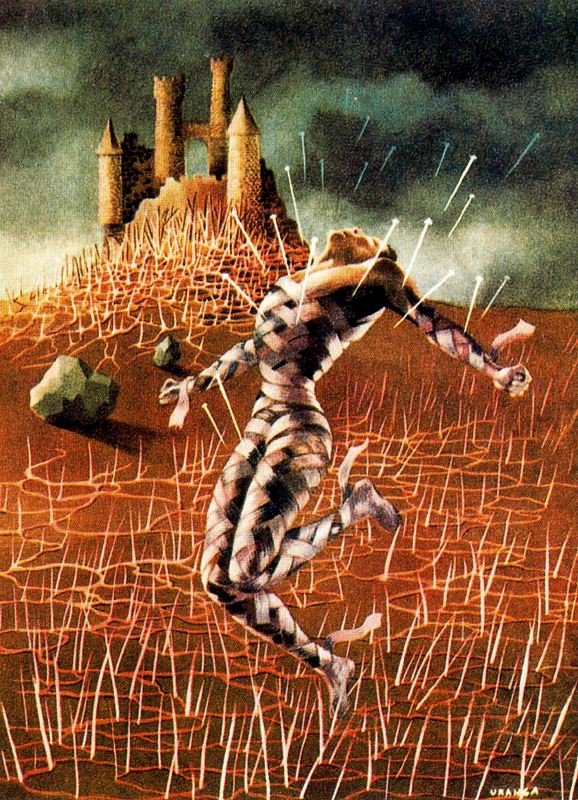

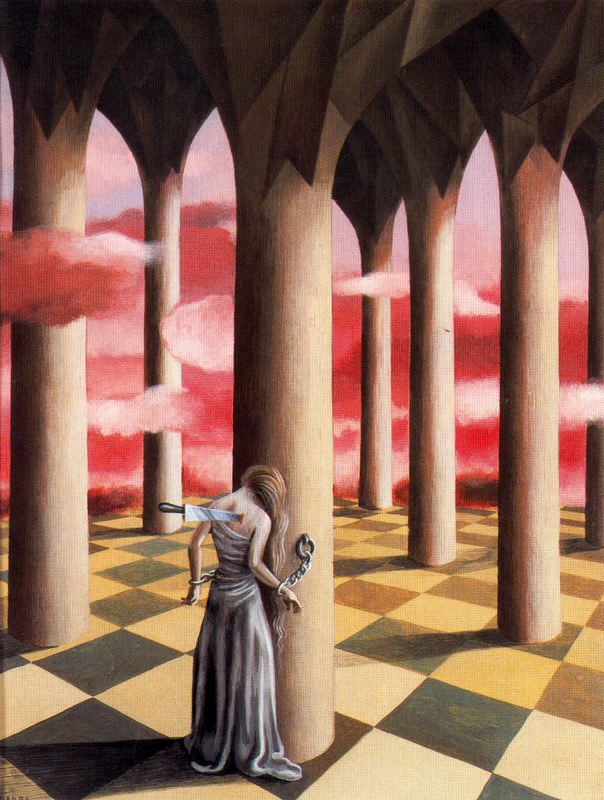

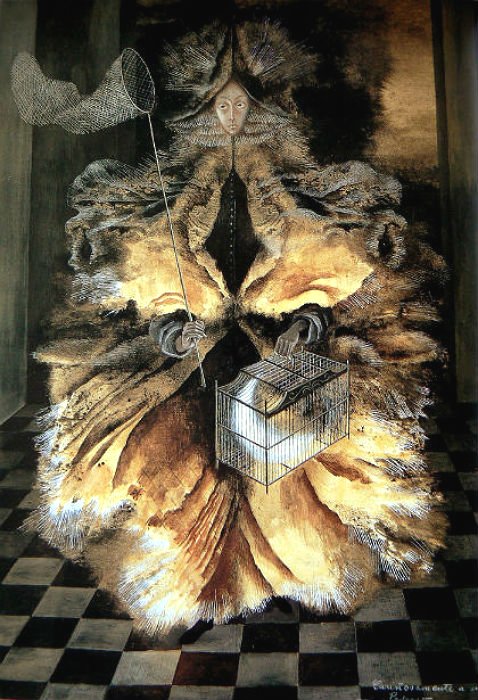

The theme of the relationship between mother and child was explored in her 1956 painting, Star Catcher. Remedios never had children although she did terminate a pregnancy when she was married to Péret saying that motherhood was more than she could handle. In this painting we see a huntress has captured the moon and carries it in a cage. The fantastic huntress is adorned in a sumptuous costume with delicately marked butterfly-wing sleeves and holds the butterfly net she has used to capture the crescent moon. The depiction is both beautiful and disturbing and the iconography is hard to read. However, the idea of imprisonment and constraint runs through many of Remedios’ paintings. It is the dichotomy between power (the huntress) and powerlessness (the captured moon) which is another recurring theme in her work.

The theme of breaking free of constraint and demonstrating female power featured in her 1962 mixed-media painting entitled Breaking the Vicious Circle. The background is a brown shapeless void A female figure stands before us. She summons all of her strength to pull apart the rope that encircles her body. This severing of the rope circle causes an electrification of her hair which stands on end and at the same time we see her torso open up to reveal a path through a forest. It symbolises the opening up of the possibilities inside her. Her subconscious thoughts are revealed which are rich and adventurous. So, what does it all mean? The breaking of the rope circle is a metaphor for the breaking free and release of the figure’s power of imagination. This breaking free from the past and tradition allows the figure to embark on a spiritual journey that had lay dormant in her heart. Look towards the floor at the hem of her cloak. In the folds of her cloak, at her feet, there is an over-sized bird, which according to Carl Jung, the Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst and great thinker who made a deep impression on Varo, this was a symbol of transcendence and so the woman has made a spiritual breakthrough.

In an earlier blog I talked about how Remedios, as a schoolgirl, was fascinated in the occult. Later in life, she studied mystic disciplines and immersed herself in metaphysical texts and in the pursuit of meaning and control. It became a passion that dominated her work. She became interested in the ideas postulated by the likes of Jung, Helena Blavatsky as well as stories about the legends of the Holy Grail, alchemy and the I Ching, an ancient Chinese divination text. It is an influential text read throughout the world, providing inspiration to the worlds of religion, philosophy, literature, and art which Remedios consulted regularly before she made decisions. She had spurned Catholicism saying:

“…What you grow up with you are given dogmatically, what you find, you conquer yourself…”

It was her search for an alternative to Catholicism featured in the depiction in her 1962 work entitled L’Ecole buissonière (literally, school in the bush but colloquially it means playing hooky). In the painting we see a youth who has skipped school and gone into the forest in search of answers. In the conical tower he finds his “friends” – the cunning fox and the wise owl which holds a crystal ball. These will be his true mentors.

An earlier painting completed in 1956 followed a similar theme of knowledge and learning. In her painting Hermitano (Hermit) we see depicted a magical figure standing alone in the woods. The body of the figure is formed by a misty six-pointed star, formed by joining together upright and inverted triangles, which symbolises equilibrium and the unification of consciousness with the unconsciousness.

If you look closely at the chest cavity of the figure you will detect the circle of yin-yang, the Chinese symbol that similarly represents the balance of opposites. The face of the figure is one of calmness and serenity and suggests inner harmony and balance.

If you look closely at the chest cavity of the figure you will detect the circle of yin-yang, the Chinese symbol that similarly represents the balance of opposites. The face of the figure is one of calmness and serenity and suggests inner harmony and balance.

When we look closely at Remedios Varo’s depictions, are we taking in every facet of her work? The American art historian, Whitney Chadwick summed it up saying:

“…Although we often see everything [on them], we can’t help feeling that we’re missing an important key that would clearly show us the meaning…”

Take for example Varo’s 1956 work entitled Three Destinies. What is going on? We see before us three figures in monk-like robes, each sitting in separate towers. One is writing, one is painting whilst the third is drinking. Each are oblivious to the presence of the other two. We also see, faintly drawn, a pully and rope systems connecting the towers. And so, what is happening?

Remedios Varo’s explanation of this depiction is that although the three figures believe they are independent, they are actually and inextricably interconnected. The fate of the three is permanently interwoven by the complicated pully system which winds around each of the three figures which makes them move, albeit they believe they are moving freely and one day in the future their lives will cross. Varo was fascinated by what she believed was just an indistinct line separating free will and determinism, the philosophical view that all events are determined completely by previously existing causes.

Remedios Varo’s last work was completed in 1963 and was entitled Still Life Reviving. The painting was one of only a few of her works which did not include a human figure. The painting was all about the cyclical rebirth of nature. Before us we see a tablecloth, eight dinner plates, various fruits and a candlestick all of which have been swept into a whirlwind by a source of energy which we cannot see. Soon it looks like a celestial depiction with the fruits acting like planets orbiting the sun, in this case, the candle flame. Look carefully at the fruit on the outermost ring. The colliding fruit explode and this then results in the seeds of the fruit being sent back to earth, the floor, where we see them magically germinate, sprouting roots and bearing small delicate green shoots. Above all this there are the diaphanous blue dragonflies that witness the goings-on and fly off to spread the news. Look at the background. Here we see a religious tone to the work with the ogival arches which sit above a chapel-like space. Varo has energised the work by adding a warm glow which also enhances the work, by her inclusion of the reds, golds and oranges of the fruit.

In 1963 Remedios suffered some health problems. She had complained of a shortage of breath when climbing stairs. She had a history of chronic gastric problems and was known to drink excessive amounts of coffee as well as being a heavy smoker. She was checked out for heart problems but was given a clean bill of health. The state of her mental health was open to doubt. Some of her friends said she was bubbly and full of life whist others said she had told them that she was depressed and did not know whether she could carry on with life. Walter Gruen, her husband, remembered the devastating afternoon of October 8th 1963, saying that he and Remedios had lunched with their friend Roger Cossio who had come to buy Varo’s painting, The Lovers. Gruen said his wife was happily explaining the details of the work to the buyer. With lunch over Cossio left and Gruen returned to his Sala Margolin shop across from their house to do some work. Shortly after, their Indian maid rushed into Gruen’s shop to tell him that Remedios was very ill. Gruen rushed home to find his wife complaining of chest pains. Gruen was unable to contact a doctor so left Remedios and went into the next room to consult some medical books. When he returned to his wife, he found that she had died.

In 1963 Remedios suffered some health problems. She had complained of a shortage of breath when climbing stairs. She had a history of chronic gastric problems and was known to drink excessive amounts of coffee as well as being a heavy smoker. She was checked out for heart problems but was given a clean bill of health. The state of her mental health was open to doubt. Some of her friends said she was bubbly and full of life whist others said she had told them that she was depressed and did not know whether she could carry on with life. Walter Gruen, her husband, remembered the devastating afternoon of October 8th 1963, saying that he and Remedios had lunched with their friend Roger Cossio who had come to buy Varo’s painting, The Lovers. Gruen said his wife was happily explaining the details of the work to the buyer. With lunch over Cossio left and Gruen returned to his Sala Margolin shop across from their house to do some work. Shortly after, their Indian maid rushed into Gruen’s shop to tell him that Remedios was very ill. Gruen rushed home to find his wife complaining of chest pains. Gruen was unable to contact a doctor so left Remedios and went into the next room to consult some medical books. When he returned to his wife, he found that she had died.

Remedios Varo died two months shy of her fifty-fifth birthday. She was buried at the Jardin Panteon, a cemetery on the outskirts of the city. The local newspapers were full of the story of her life and her untimely death. Margarita Nelken, a close friend and a journalist for the Mexico city newspaper Excelsior wrote:

“…Remedios Varo, one of the greatest artists of modern Mexico, and – without exaggeration – of contemporary painting, on Tuesday evening left us forever. Unexpectedly. So discreetly, quietly, just as she had lived among us…”

Alfonso de Neuvillate, the art critic for the Novedades newspaper wrote:

“…Unjust, inexplicable…..on Tuesday, the eighth of October at 7pm, death ended the life of one of the most individual and extraordinary painters of Mexican art, Remedios Varo. A heart attack. One asks the questions like, why her? Why not someone mediocre?…”

Most of the information for this blog, apart from the usual sources, comes from Janet A. Kaplan’s excellent book entitled Remedios Varo, Unexpected Journeys. This is a must-read book if you want a fuller version of the life and times of Remedios Varo.

In her early days in Mexico, Remedios did few paintings and spent most of her time writing. She and Leonora Carrington would write fairy tales, collaborated on a play, invented Surrealistic potions and recipes, and influenced each other’s work. The two women, together with another of their friends, the photographer Kati Horna became known as “the three witches”

In her early days in Mexico, Remedios did few paintings and spent most of her time writing. She and Leonora Carrington would write fairy tales, collaborated on a play, invented Surrealistic potions and recipes, and influenced each other’s work. The two women, together with another of their friends, the photographer Kati Horna became known as “the three witches”