Marriage and Personal Tragedy

During the three-year period between 1901 and 1904 Anna, her father and young brother went on several painting trips. They travelled through Europe to Norway as well as taking a couple of trips around the east coast of America. Anna and her father, the painter, William Trost Richards, had joint exhibitions of their work in New York, Boston and Washington at which twenty of her works she had completed in Clovelly were displayed.

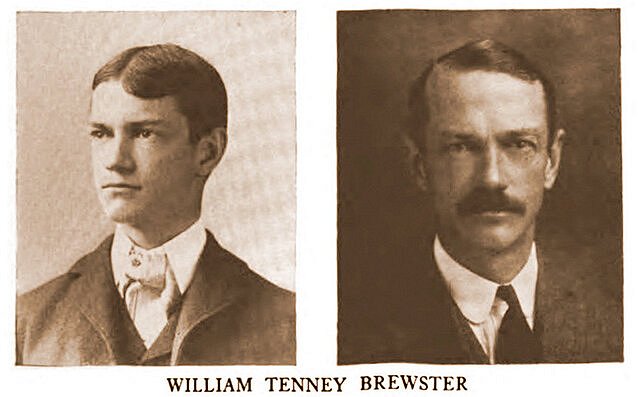

In 1904 whilst Anna was enjoying a trip back home in Boston she got news that her elderly friend and patron, Mr Kemp-Welch, had died. During her stay in America, she went to New York to visit her brother Herbert who was a professor of Botany at Barnard College, Columbia University. Whilst with her brother she met his roommate a professor of English literature, William Tenney Brewster. From that first meeting with him the pair spent many hours together during Anna’s two-week American vacation. She eventually sailed back to England but the pair corresponded regularly. Their friendship blossomed and in January 1905, William proposed marriage to Anna.

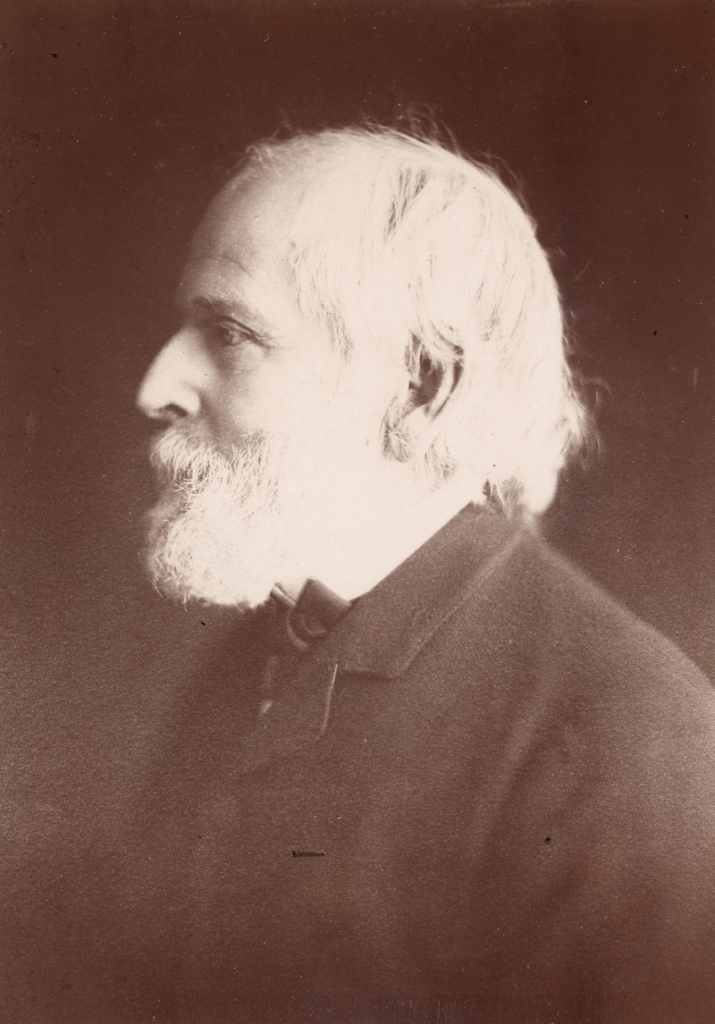

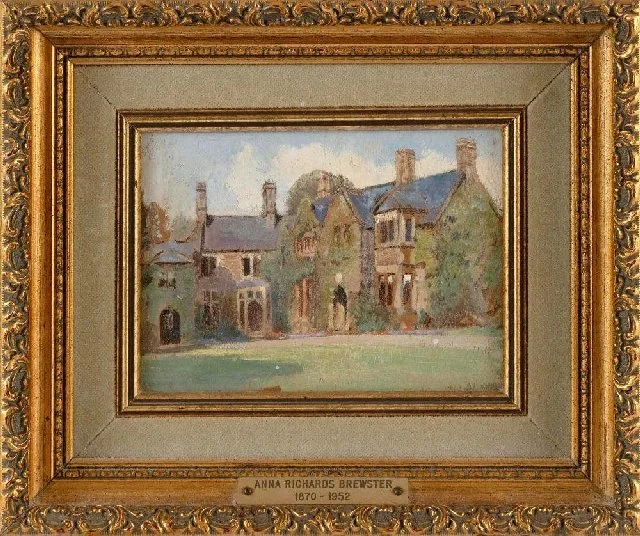

William Trost Richards in his Newport Studio by Anna Richards Brewster (1892)

Anna didn’t accept right away as she had a lot to think about. She wanted to carry on being a professional artist and she was concerned that marriage would interfere with that as it had done to so many female painters who had chosen married life over the role of a professional painter. In March, after much soul searching, Anna agreed to marry William and they were married on July 18th 1905 at the Parish Church of St Luke in Chelsea and she became Mrs Anna Richards Brewster. The couple went on honeymoon and for the first part of it her father and brother, Herbert, accompanied them.

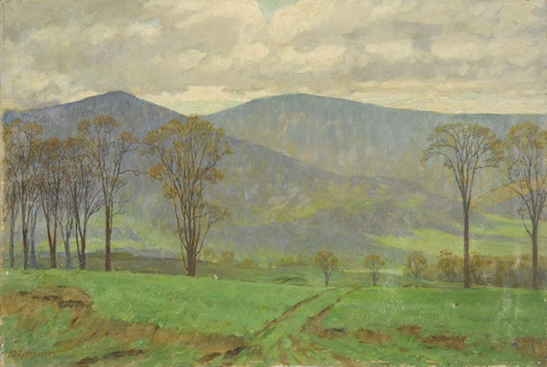

Landscape with Wild Flowers by Anna Richards Brewster (1901)

Anna and William decided that they must live in New York because of his teaching post and they settled on a plan to rent two apartments on the same floor of a building on the upper west side of New York, one for them and the other for her father and brother. The plan was to share meals and staff and one room in the second apartment would be set up as a studio for Anna and her father. The plan never came to fruition as in the Autumn of 1905, her father, William Trost Richards had a heart attack, whilst working on a large painting in his Newport studio on a large painting, and died.

Anna’s worries about her dual role as a wife and a professional artist proved unfounded as her husband pushed her to continue painting and exhibiting her work even while her life and interests were changing. Anna was content with how her life had evolved and wrote to her friend Annie Winsor in 1906 telling her about her new sense of purpose:

“…The sense of permanency — of its being ‘the real thing’ as it were, in marriage is a comfort and a struggle to me and I like the problems of life becoming less shadowy and unreal than they are to a single person. I have always felt irresponsible — a spectator before; but now at last I am in the arena…”

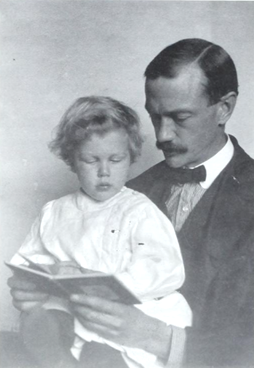

Anna Richards Brewster with her three-year-old son Herbert (1908)

William Tenney Brewster with his son Herbert (1909)

In 1906 Anna gave birth to her first child, a boy, and she and her husband named him Herbert, presumably after her brother. It proved to be a complicated birth and at one point the lives of mother and baby were in peril. In June 1906 in a letter to Annie Winsor, Anna described the traumatic birth and her proud husband:

“…It was a capable doctor who saved us — and indeed it was all they could do to save the little hoy’s life…. The boy is doing well now…. he is his father’s son — Dick [i.e. William Tenney Brewster] is delighted with and about him. He was charming and spontaneously devoted all the time — I think it is the profoundest experience he has ever had. I didn’t suppose he would care so much so soon….. I’m sorry that the child is rather a ticklish one to take care of, being excessively sensitive to heat and cold — his circulation is bad. It is so hard to get one’s experience with babies: for experience is won through mistakes: and mistakes are disastrous with babies…”

From the letter we can deduce that the baby’s health was an issue which would later haunt them. The early years with baby Herbert were talked about by Edith Price, Anna’s niece, in a May 1986 interview with Susan Brewster McClatchy.

“…Of course they spoiled him dreadfully. … He was the wonder of wonders and she had ideas she had gotten from some German child health expert at the time, that you let them run around naked…. Anyway, he was such a poor, puny, one-foot-in-the-grave little baby that mother [Anna’s sister Nelly] said. “He’s off to an awfully bad start.” Well, the German exercises did him good and he became quite a sturdy little boy…”

Once again we get the feeling that all was not right with baby Herbert.

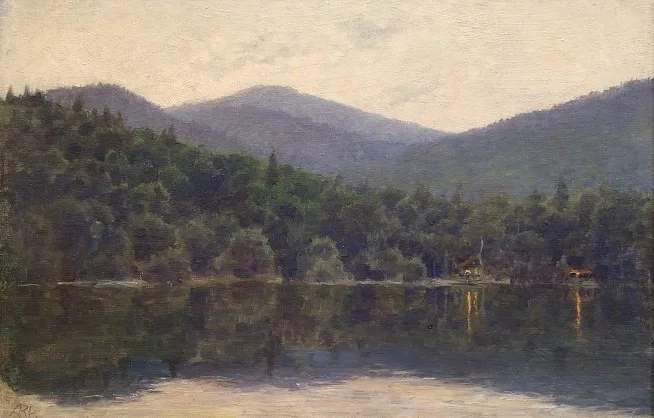

Campfire Long Pond ME by Anna Richards Brewster

Lily Pond Matunuck Rhode Island by Anna Richards Brewster (1915)

When Anna’s father died he left Anna and her husband a property on Cedar Swamp Pond in Matunuck, Rhode Island, as a wedding present. There they built a small summer camp, and it was here that the couple would spend the next thirty summers.

Palma Majorca by Anna Richards Brewster (1932)

Meanwhile, Anna’s best friend Annie Winsor, an educator, was living with her uncle William Ware, who owned a boarding house in New York. She taught at the Brearley School, an all-girls private school in New York City, located on the Upper East Side. Her uncle had also invited Annie’s distant cousin, Joseph Allen to come and live with them. Joseph, a Harvard graduate, had been teaching at Cornell and in 1897 began teaching at the City College of New York. Annie and Joseph’s friendship turned to love and the couple were engaged in 1899 and married the following year. The couple had three children by 1905 and decided that New York was not an ideal place to bring up children and so they moved to White Plains, a town in Westchester County, a northern suburb of New York. Unfortunately Annie found the schooling there was below her standard and decided to home-school her children and from this she also began to teach the children of her neighbours. In 1907, buoyed by the success of teaching the neighbourhood children she founded the Roger Ascham School, a progressive, co-education school that included all grades from first to high school. Later the school relocated to the nearby town of Scarsdale.

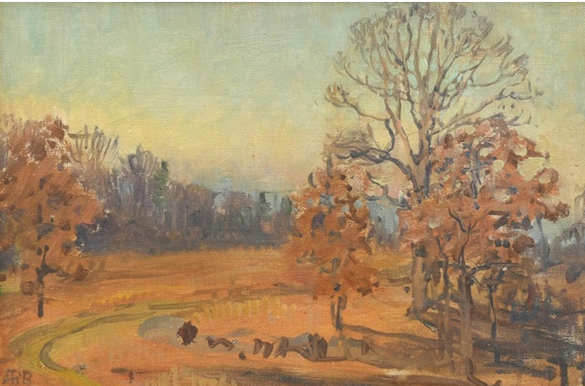

Autumn Path by Anna Richards Brewster (1915)

Anna Richards Brewster and her husband William decided, for the same reason as Annie and her husband, that New York city life was not the place to raise their son Herbert and they too moved to Scarsdale and built themselves a house. Anna immersed herself in the Scarsdale community, founding the Scarsdale Art Association, and helped to found the Scarsdale Women’s Club. She also became a trustee of her friend Annie Winsor Allen’s Roger Ashcam School in 1909. Despite the upheaval of bringing up her son, looking after her husband and the issues around re-location she still managed to exhibit works at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts

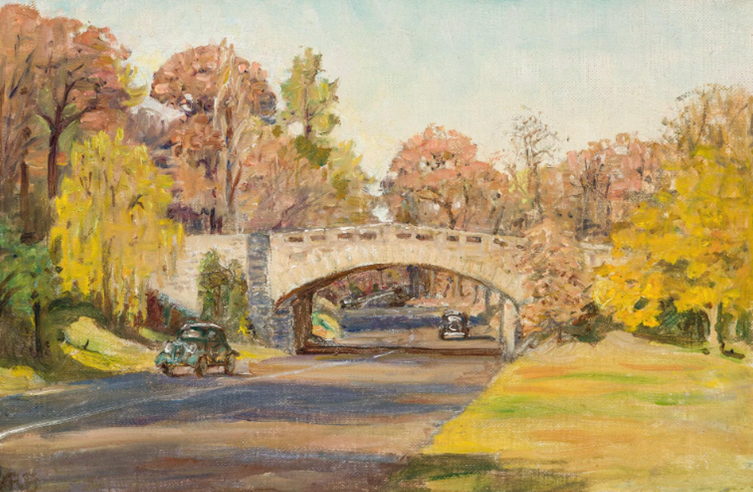

Butler Road, Scarsdale, New York by Anna Richards Brewster

In January 1910, a month before the completion of their new house in Fenmore Road, Scarsdale, their son Herbert was taken seriously ill and tragically passed away. The cause of death was believed to have been complications from a bout of pneumonia. Anna and her husband William were devastated. Edith Price, Anna Richards Brewster’s niece, remembered that sad time in an 1986 interview:

“…The house that was to be for their boy was being built through the Winter of 1909 and early months of 1910, but in February there was no child. It was a beautiful house. . . . I saw it first in 1913 , when I went alone to visit. It was overwhelmingly haunted, for me, and always remained so. . . . The little presence that their love and lasting loneliness had caused to dwell there was inescapable…”

Twenty years later Edith revisited the house and recalled that visit:

“…I slept in the nursery, whose pictures I had secretly copied many years before. . . . Anna had meant to paint fairytale scenes in a high dado all around the room. Instead there were pictures of a three-year-old hoy — in the snow on Riverside Drive, in the woods at Cedar Swamp. It must have helped many dark hours – painting them – trying to hold him from slipping away. I wonder what WTB [Anna’s husband] did with those paintings. I would dearly love to have one. I wonder if he destroyed them…”

The paintings were never found.

The outward appearance of Anna and her husband after the death of their son was one of resignation and yet they seemed to have recovered but I am sure inwardly their minds were in utter turmoil, but life still had to go on.

No. 9 Fenemore Road, Scarsdale in Early Autumn by Anna Richards Brewster

In February 1910 the construction of their new house was completed and they moved in. Anne returned to her painting but only showed her work infrequently. The couple still spent the summers at their cottage in Matunuck, Rhode Island. William carried on lecturing but every seven years Barnard College allowed him to take a year’s sabbatical and during those twelve months he and Anna would travel.

Camogli [Italy by Anna Richards Brewster (1933)

Portofino by Anna Richards Brewster

Their European journeys took them to the Lake Como area of Italy and Camogli, a seaside town close to Sorrento and towns such as Portofino on what is now known as the Italian Riviera.

Via Dolorosa, Jerusalem by Anna Richards Brewster

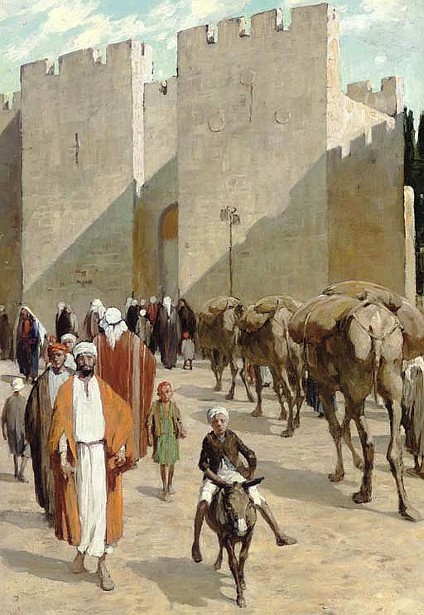

Outside the Jaffa Gate, Jerusalem by Anna Richards Brewster

A Market In Biskra, Algeria by Anna Richards Brewster

They also travelled to the Middle East and North Africa and Anna recorded their journey through her paintings.

In 1919 William Brewster was due to take another one-year sabbatical and he and his wife had once again planned to travel abroad but their plans changed when he was offered and accepted a position with the University Union in Paris. He was tasked with converting this private club for wealthy American military officers to a civilian educational establishment now that World War I was almost over. Consequently, Anna and William decided to rent out their Scarsdale property and she would take up residence at the Metropolitan Club in New York City while her husband found an apartment tor them in Paris.

However, the plan and his position within the organisation ended badly probably due to the directors not willing to go along with William’s revolutionary ideas. He had wanted to integrate the American students with the French and this would include finding them housing in French homes. Even more distasteful to the directors was William’s plan to provide scholarships for middle-class Americans and to open the programme to women students. William’s post was severed. However, their Scarsdale home had been rented out and so Anna had to spend the next year living in New York City.

Ardsley Road Bridge by Anna Richards Brewster

Besides depicting the various places she and William visited abroad she completed numerous sketches of rural Scarsdale before it became industrialised which she often used to complete finished works. Her husband recalled her interest in their neighbourhood, he wrote:

“…She sketched deftly, accurately and rapidly and thus in more than sixty active years, made thousands of sketches all drawn and coloured on the spot… From such sketches she often made larger and more finished pictures…”

Anna received many painting commissions including a portrait commission to paint the portraits of eight professors at Columbia University and closer to home she was also asked to paint a portrait of the founder of the Scarsdale library.

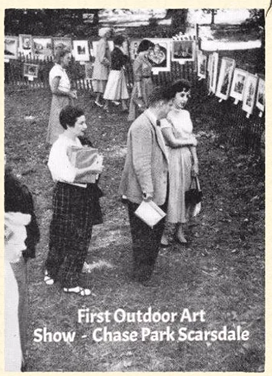

First exhibition of the Scarsdale Art Society

Throughout the 1930s, Anna and her husband would take many trips to Europe, especially Italy, a country they both loved. Anna tirelessly sketched during these journeys of discovery. In 1938, Anna founded the Scarsdale Art Association and for many years she would offer to tutor members at her house.

Tucson Arizona by Anna Richards Brewster (1940)

Anna Brewster’s painting of Tucson comes from a group of works found in her studio at the time of her death in 1952. It was one of a select number of pieces that her husband, William Tenney Brewster, included in a privately published book in 1954 titled A Book of Sketches by Anna Richards Brewster.

In 1950 Anna’s health began to deteriorate and her sight became very limited causing her to stop painting. On May 23rd 1952 she suffered a stroke and on August 21st 1952 Anna Richards Brewster died, aged 82.

In the book of Anna’s sketches that her husband published in 1954, he described his wife’s style and innate talent. He wrote:

“…She could do about anything in oil, watereolor, paistel, pen and ink and pencil: from portraits to miniatures; from actual gardens to charming assemblages of flowers; from comic skits to wholly sober and serene representations of people and places. As her father said, ‘She could have had wide success if she had chosen one line and developed a speciality but she preferred to express her wide range of sympathies.’ . . . Of the various forms that I have spoken of, by far the most characteristic are the oil sketches. They are the most numerous; the two thousand that she left at the time of her death are hardly half of what she made in sixty years. . . . She painted very rapidly, with little reliance on the eraser or paint rag and was able to find something interesting anywhere. Her gear was the simplest. I never knew her to tote an easel or stretched canvas. … A small box with a block of canvas about seven inches by five sufficed . . . for larger sketches, a box about nine by thirteen was the thing. The larger sketches are more numerous and more detailed than the smaller, but neither kind occupied more than a single sitting or was continued after an interruption. A sketch in the morning and another in the afternoon would be not uncommon…”

Some of the information was gleaned from the usual search engines but most came from a 2008 book entitled Anna Richards Brewster, American Impressionist which was a collection of essays edited by Judith Kafka Maxwell with contributions from Wanda Corn, Leigh Culver, Judith Kafka Maxwell, Susan Brewster McClatchy and Kirsten Swinth.