Viktor Madarász & Pal Szinyei Merse

Museum Of Fine Arts Budapest

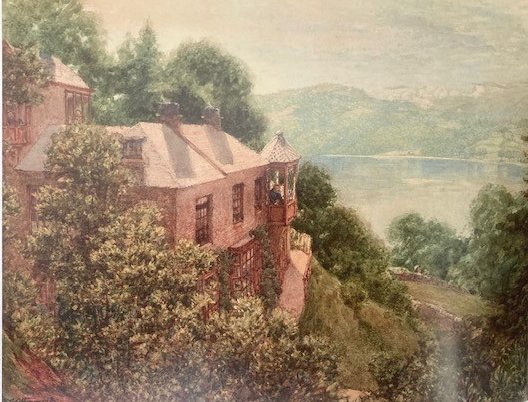

Buda Castle

I visited the Hungarian city of Budapest the other week and decided to visit some of its art museums. The two main establishments are the Szépművészeti Múzeum, the Museum of Fine Arts on the Pest side of the city and the Hungarian National Gallery on the Buda side of the city which is located inside the royal palace of Buda Castle, and the vast collection there traces the country’s creative history from medieval triptychs through to post-1945 art and sculpture. In the following blogs I want to look at the works of art of the Hungarian painters which feature predominantly in these collections.

Viktor Madarász

Self portrait by Viktor Madarász

Viktor Madarász was born on December 4th 1830 in the small village of Csetnek, (today: Štítnik, Slovakia) in what is now middle-eastern Slovakia. He came from a once noble family. His father, András was an iron manufacturer and craftsman. Originally, his parents wanted Viktor to have a career in law and so he went to study in Bratislava. The majority of Hungary had been under Ottoman rule from 1541 and 1699 at which time the Habsburg monarchy defeated the Ottoman forces and took control over Hungary.

In 1848, when the Hungarian Revolution began, Madarász left college to join the struggle for independence. Despite being only seventeen, which was too young to join the army, he was accepted and participated in numerous battles and became a Second Lieutenant. The revolution failed and for Madarász the experience was traumatic and one which he never forgot. He dedicated his art to the idea of Hungarian independence from Habsburg rule for the Hungarian people and recalled pictorially the heroic and tragic memories of this time in the history of Hungary.

Kuruck and Labanc by Viktor Madarász

One of his early historical paintings was entitled Kuruc and Labanc which depicted two brothers fighting on opposite sides of the Hungarian Revolution. The Kuruck was a group of armed anti-Habsburg grouping that wanted to rid Hungary of the Habsburg rule and the word “kuruck” is used in both a positive sense to mean “patriotic” and in a negative sense to mean “chauvinistic.” The term Labanc was designated to those Hungarians who advocated cooperating with the outside powers, the Habsburgs, and is almost always used in a negative sense to mean “disloyal” or “traitorous”. The painting was well received by the critics.

Thököly’s Dream (The Dream of an Exile) by Viktor Madarász (1856)

Dózsa’s People by Viktor Madarász

After the war of independence, the uprising had been defeated, and Madarász lived in exile and after hiding out briefly, returned on foot to his family’s home in Pécs. Once back home he continued with his legal studies but also enrolled in art lessons from a local artist. In 1853, he enrolled for preparatory work at the Academy of Fine Arts, Vienna but was disheartened with the old-conservative atmosphere there, and he went to the private school of Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller, who was looked upon as a bold innovator at the time. In 1856, Viktor Madarász moved to Paris where he studied in the studios of Léon Cogniet and at the École des Beaux Arts.

The Mourning of László Hunyadi by Viktor Madarász (1859)

One of Madarász most popular works and considered the main work of his life, is part of the Hungarian National Gallery collection. It is entitled The Mourning of László Hunyadi and was completed by Madardsz in 1859 whilst he was living in Paris. It is a major work of romanticism. The painting depicts the altar of the Church of Mary Magdalene in Buda, before which is the body of László Hunyadi. László Hunyadi, the son of János Hunyadi, who had defeated the Ottomans and became a national hero, was ordered to be killed by Vladislav V. Young Hunyadi enjoyed widespread popularity among the Hungarians, so he was seen as a threat to the seventeen-year-old, inexperienced King Vladislav V, the only son of the Habsburg German King Albert II. The king, fearing the popularity of Hunyadi, ordered his execution and he was beheaded on March 16th 1457. In this depiction we see two women kneeling at the feet of Hunyadi. One was his mother, Erzébet Szilágyi, the other was his bride, Maria Gara. This painting by Madarasz was believed to be an anti-Habsburg political statement during a time of the Habsburg oppression of the Hungarian people. The work of art became a symbol of the failed Hungarian Revolution and National self-sacrifice. The painting was thought of as the Hungarian Pieta following the iconography of the Lamentation of Christ, in which Christ’s torso was removed from the cross and his friends mourned over his body and so in a way Madarasz’s painting offered a promise that like Christ, the Hungarian nation would rise again.

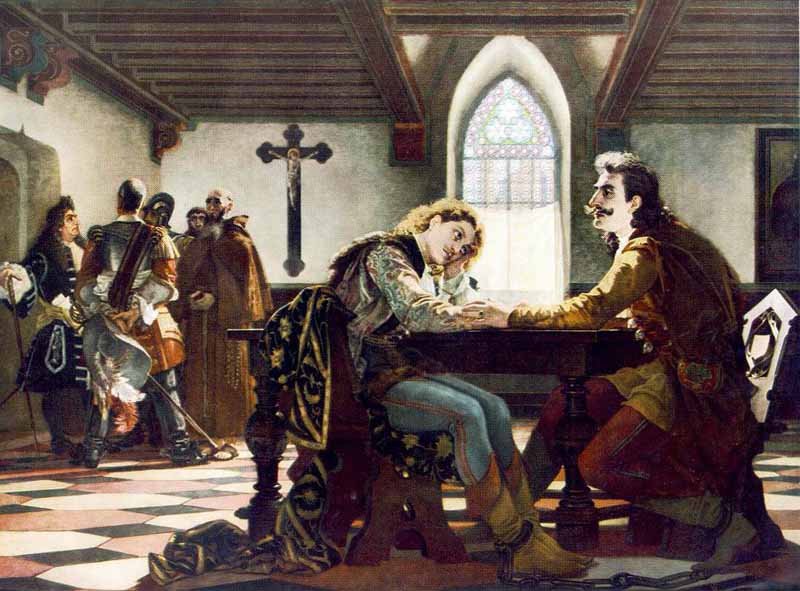

Zrínyi and Frangepán in Bécsújhely Prison by Viktor Madarász (1864)

Another painting in the Hungarian National Gallery by Madarász was his 1864 historical work entitled Zrínyi and Frangepán in Bécsújhely Prison. When the painting was first exhibited in 1866 people flocked to see it. The painting depicts two men, Péter Zrínyi, the Ban (local ruler) of Croatia, and the Hungarian Count Ferenc Frangepán, sitting facing each other across a table in the Bécsújhely prison. Guards and imperial officials can be seen in the background. Both had been implicated in the Wesselényi Conspiracy, a plot among Croatian and Hungarian nobles to oust the Habsburg Monarchy from Croatia and Hungary. The two men are saying their last farewells to each other before they were both executed.

Pal Szinyei Merse

Self portrait by Pal Szinyei Merse (1897)

The second artist I am showcasing is Pál Szinyei Merse. Pál Szinyei Merse was an outstanding master of nineteenth-century Hungarian painting and one of the most influential figures in Hungarian art. He was born on July 4th 1845 in Szinyeújfalu, a village and municipality in the Prešov District of eastern Slovakia.. He was the third of eight children of Félix Szinyei Merse and Valéria Jekelfalussy and came from a noble family which had 700 years of history, but by the 19th century the family wealth had dwindled, and yet, Pál, because of his art, never ever had problems making ends meet.

Winter by Pal Szinyei Merse (c.1905)

After the death of his grandfather in 1850, the family moved to the mansion in the east Slovakian town of Jernye (now Jarovnice). His father graduated in law from Košice and became ambassador to the town of Sibiu during the 1839/40 Parliament, and was appointed Alispan, an office held by the most prestigious and generally wealthiest of the commoners and in 1871 became the High Sheriff. His father was a great supporter of his son and his artistic ambitions, and his mother was a lover of literature and music, who brought considerable wealth into their marriage.

Skylark by Pál Szinyei Merse.(1882)

From 1856 Pál studied at the Catholic high school in Prešov and remained there until he reached the sixth grade. He remained a private student until 1859, and, in the autumn of 1861, he studied in Oradea, where he graduated in the summer of 1863. Pál Szinyei started to become interested in painting and took it more seriously during his high school years and received tuition from Lajos Mezey a local artist from Oradea.

The Field by Pál Szinyei Merse (1909)

In 1864, thanks to the support of his parents, he enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, where he studied under the Hungarian artist, Alexander von Wagner, and later, from 1867 to 1869, his tutor was Karl von Piloty, the German historical painter. Another famous artist he met whilst attending the Academy was Wilhelm Leibl, who introduced Pál to plein-air painting. After seeing a major art exhibition in 1869, Pál was anxious to get to work on his own and decided to leave the Academy. Pál Szinyei Merse was a ground-breaking pioneer and the first true colourist in the history of Hungarian painting.

On October 15, 1873, Pál Szinyei Merse married the love of his life, Zsófia Probstner, the twenty-year-old daughter of the owner of the Lublo bath. They went on to have six children, a son, Laszlo Paul Felix and five daughters, Sophie, Mary, Valeria, Elisabeth and Adrienne.

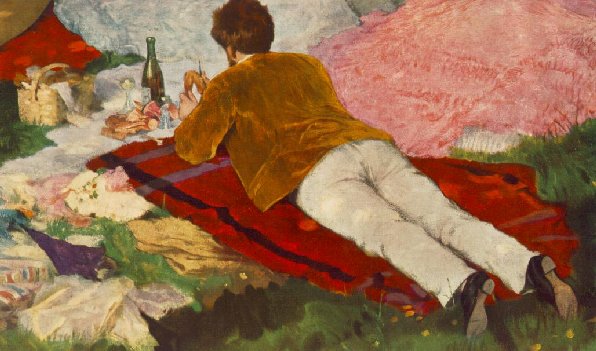

Picnic in May by Pál Szinyei Merse (1873)

In 1873 Pál Szinyei Merse completed the painting entitled Picnic in May and although it was ridiculed by his contemporaries it is now looked upon as one of the finest Hungarian paintings.

In his autobiography Pál wrote about the painting, saying :

“…I painted myself into the picture prone, minching away, with my back to the spectator. I must admit I was thinking of the critics who would dislike my picture…”

Lady in Violet by Pál Szinyei Merse (1874)

Probably one of his most famous works was painted a year later, 1874, and is entitle Lady in Violet. It is seen on many posters around Budapest advertising the Hungarian National Gallery. It has become the Hungarian Mona Lisa and is one of the most well-known painting to this day.The painting depicts the artist’s wife, Zsófia, who was pregnant at the time, resting in the garden of their manor house in Jernye. She is wearing a taffeta bustle dress which was very popular in those days. The artist started the painting using complementary colours and then created a new colour harmony by juxtaposing yellow, violet and green. While he was in Munich he had bought the high-quality violet paint from Richard Wurm, a paint merchant and a mutual friend of both Pál Szinyei Merse and the Swiss Symbolist painter, Arnold Böcklin. It was Böcklin who encouraged Pál to use colour vigorously.

The Artist’s Wife Dressed in Yellow by Pál Szinyei Merse (1875)

The painting of his wife, which was never finished, was painted a year after his painting, Lady in Violet.

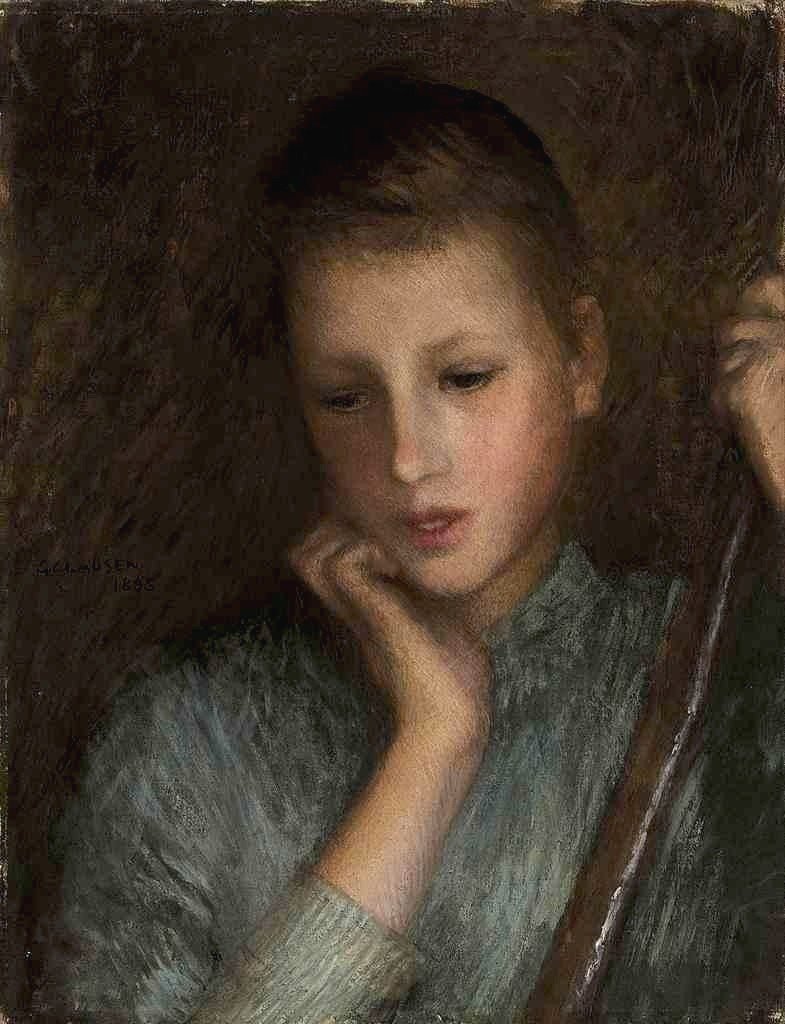

Portrait of Zsigmond Szinyei Merse by Pál Szinyei Merse (1866)

His family featured in many of his painting, such as his 1866 painting, Portrait of Zsigmond Szinyei Merse which he completed while spending his summer in Jernye. It is a depiction of his younger brother Zsigmond with a red cap, lost in thought as he plays a chibouk.

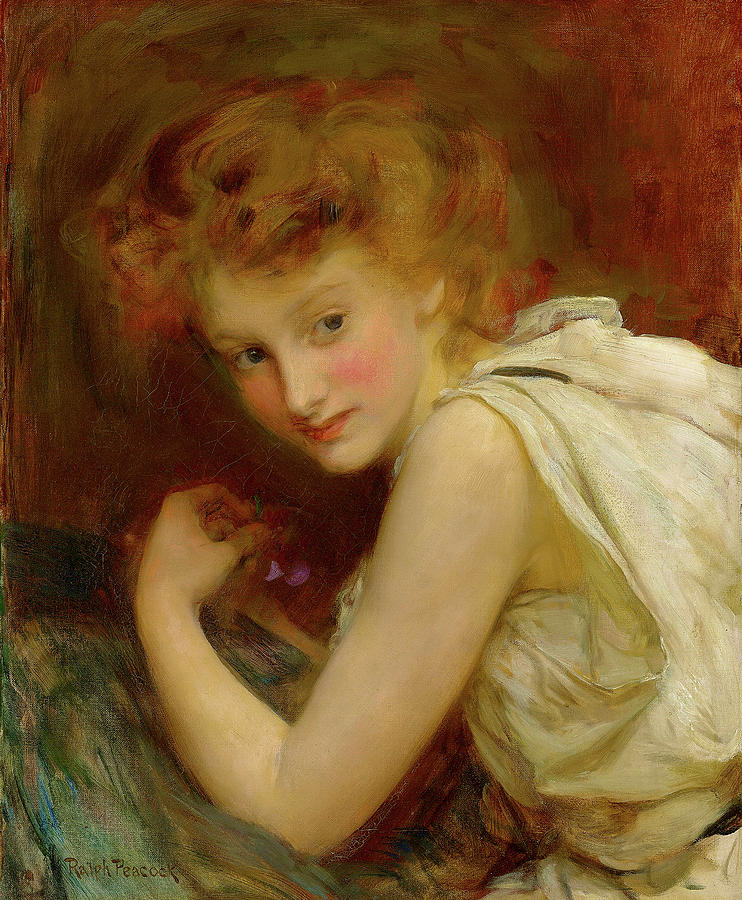

Portrait of Ninon Szinyei Merse by Pál Szinyei Merse (1870)

Pál Szinyei was working in Hungary during the French-Prussian war and painted several pictures of members of his family in a naturalist style. This portrait of his elder sister is one of them.

Portrait of Artist’s wife by Pál Szinyei Merse (1880)

Lovers by Pál Szinyei Merse (1869)

One of Szinvei’s favourite themes was outdoors parties and the enjoyment of periods of relaxation. His 1869 painting entitled Lovers depicts two people relaxing in a rural setting, on a hillside during the early summer. The artist has used pale colours which he has used harmoniously and this muted colouration evokes a lyrical aspect to the scene. It is a scene of great intimacy as we see the couple lock eyes whilst their fingers tenderly intertwine and set in an almost dream-like countryside background.

…….to be continued