Dorothea Tanning (1944)

By the later part of 1942, Dorothea Tanning was well established with the Surrealist Movement within the New York art scene. At the party hosted by the art dealer, Julien Levy and his wife, Muriel, she had been introduced to many of the Surrealist luminaries who were living in New York, including the German-born painter, Max Ernst. Following on from his meeting with Dorothea, he visited her at her sprawling, sparse apartment studio to look at her paintings.

It was not just idle curiosity that had brought Ernst to Tanning’s studio but he had come at the behest of his then wife, the art collector and socialite, Peggy Guggenheim, in order to select one of Dorothea’s paintings for the Exhibition by 31 Women. This exhibition was organized by Peggy Guggenheim and ran for a month starting on January 5th 1943 in her New York gallery and included works by Frida Kahlo, Louise Nevelson, Leonor Fini, Gypsy Rose Lee, and Leonora Carrington. Many of the artists were Surrealists, and many were wives of artists with whom Guggenheim was acquainted. Georgia O’Keeffe declined an invitation to participate in the show, saying that she refused to be categorized as a “woman painter.”

Birthday by Dorothea Tanning (1942)

The one painting which caught Max Ernst eye was the one Dorothea completed around the time of her thirty-second birthday, simply entitled Birthday, a title actually suggested by Ernst. It is a self-portrait. She has depicted herself in the process of metamorphosis. She stands before us semi-naked. Her hair is pinned back and she is wearing an Elizabethan-style purple silk and lace shirt, open to the waist, exposing her chest and breasts. Her direct and open gaze emanates a sense of calm. Her semi-naked stance is probably her way of challenging her oppressive past and demonstrating her desire to rid herself of past parental control when she was a recalcitrant teenager. She does not fear people looking at her body as this is how she sees herself.

Her skirt seems to be disintegrating and being replaced by a thick layer of jagged brambles that cascade down to her bare feet. However, look closely at the brambles and you will see that they are made up of writhing naked bodies which are spiralling and intertwined to create a fabric of woodland sprites which adds a touch of menace to the depiction. On the floor in front of her crouches a winged famulus. The art historian Whitney Chadwick called it the “winged lemur.” These fantastic animals are associated with the night and the spiritual world and are a combination of hybrid parts, a fusion between realism and fantasy, the commonplace and the supernatural.

The other interesting aspect of this work is what we see on the right of the depiction. Within the confines of her apartment, we see a passageway which leads to a suite of rooms with doorways in line with each other, known as an enfilade.

The catalogue for the 1944 exhibition held in New York, Abstract and Surrealist Art in America, contained a piece by Dorothea Tanning in which she described her painting, Birthday. She wrote:

“…One way to write a secret language is to employ familiar signs, obvious and unequivocal to the human eye. For this reason, I chose a brilliant fidelity to the visual object as my method in painting Birthday. The result is a portrait of myself, precise and unmistakable to the onlooker. But what is a portrait? Is it mystery and revelation, conscious and unconscious, poetry and madness? Is it a demon, a hero, a child-eater, a ruin, a romantic, a monster, a whore? Is it a miracle or a poison? I believe that a portrait, particularly a self-portrait, should be somehow, all of these things and many more, recorded in a secret language clad in the honesty and innocence of paint…”

Fifty-five years later in 1999, the painting was bought by the Philadelphia Museum of Art and in the brochure which accompanied the survey show eighty-nine-year-old Dorothea Tanning once again talked about the work, saying:

“…It was a modest canvas by present-day standards. But it filled my New York studio, the apartment’s back room, as if it had always been there. For one thing, it was the room: I had been struck one day by a fascinating array of doors – all, kitchen, bathroom, studio – crowded together, soliciting my attention with the antic planes, light, shadows, imminent openings and shuttings. From there it was an easy leap to dram of countless doors. Moreover, alone and taking stock of myself, I felt a sort of immanence as if my life was revealing itself at last – real birthday…”

Self-portrait by Leonora Carrington (1938)

Many art critics highlight the similarities between Tanning’s self-portrait which is in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the self-portrait done four years earlier, in 1938, by another Surrealist painter, Leonora Carrington, which is housed in the Metropolitan Museum of art in New York. Both paintings combine fantasy and reality, each artist is depicted in the company of some magical creature.

The Magic Flower Game by Dorothea Tanning (1941)

Similar to the depiction of the girl transforming in her self-portrait painting, Birthday, we can once again see another transformation in her painting The Magic Flower Game in which a boy is depicted in a state of organic transformation. The boy in the painting is part human and part fashioned of beautifully coloured flowers which lie flattened against his legs and thighs like a second skin. They also burst from his back in an assemblage of colour. Again, his two upper limbs are part human and part nature with one being a branch-like appendage which end in claws. In his hand he holds a ball of thread that seems to have come from the petals of a sunflower which lies at his feet. Behind him in the fireplace we see the blue sky on which is the outline of a cat. A second figure, possibly a mirror image of the boy is seen disappearing into the wall above the mantlepiece. This part human, part nature is a classic occurrence of juxtaposition which is familiar in Surrealist works of art.

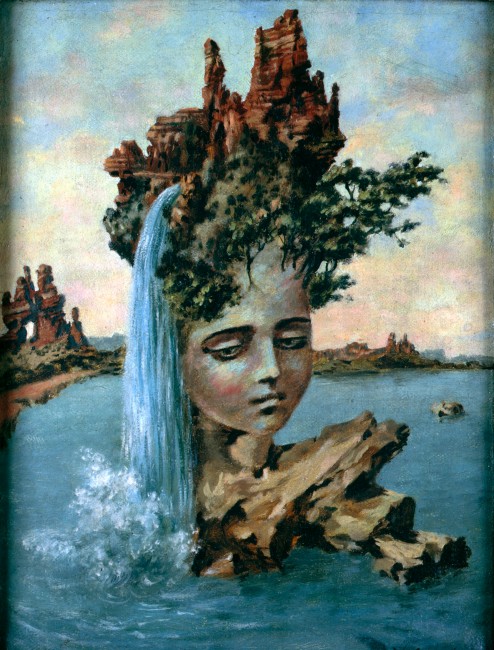

Arizona Landscape by Dorothea Tanning (1943)

Dorothea Tanning often delved into the motif of hair as being symbolic of transformation in her early 1940’s paintings. It was almost her iconographic autograph. One of my favourite works of this type was her 1943 painting entitled Arizona Landscape.

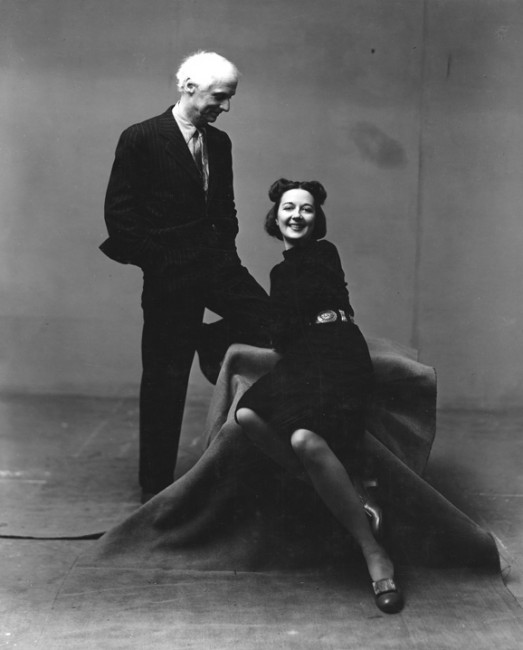

Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning (1947)

Dorothea’s encounter with Max Ernst, Peggy Guggenheim’s husband, prior to The 31 Women exhibition, led not only her having one of her works included in the show but led to a romantic entanglement with Guggenheim’s husband. Max Ernst left his wife and went to live with Tanning and the couple eventually married in a double wedding with photographer Man Ray and Juliet Browner in Beverly Hills, California in October 1946. This was Ernst’s fourth marriage and Tanning’s second and for both of them it was their last. Guggenheim expressed her sadness in losing Ernst to Tanning and painfully and caustically recalled the important exhibition, famously saying: “I should have had 30 women.”

Eine Kleine Nachtmusik by Dorothea Tanning (1943)

Dorothea Tanning and Max Ernst first visited Sedona, Arizona together in 1943. He had first visited Sedona in 1941 with his son, Jimmy, and his third wife, Peggy Guggenheim. Dorothea and Ernst rented a small studio space and it was in Sedona that Tanning painted her masterpiece, Eine Kleine Nachtmusik. It is another painting in which the motif of hair is depicted and is one of her most famous early works, which she also completed in 1943. The painting is now part of the Tate Modern’s collection in London. It depicts what appears to be a hotel corridor along which are numbered doors on the left and a steep stairway on the right, the door at the end is open slightly and offers us a glimpse of light radiating from within. On the floor of the landing, we see the head of a giant sunflower. Two of its petals lie on the stairs to the right and a third is held in the hand of a life-like doll which lies against one of the doorways. There is a similarity between the tattered clothes worn by the reclining doll and the girl walking along the hallway. It could be that the ragged state of the clothes worn by both the doll and the girl indicate that a struggle with a malevolent force may have taken place and note how the girl’s long hair streams upwards as if blown up by an extremely forceful gust of wind. Tanning herself commented on the meaning of her painting saying:

“…It’s about confrontation. Everyone believes he/she is his/her drama. While they don’t always have giant sunflowers (most aggressive of flowers) to contend with, there are always stairways, hallways, even very private theatres where the suffocations and the finalities are being played out, the blood red carpet or cruel yellows, the attacker, the delighted victim…”

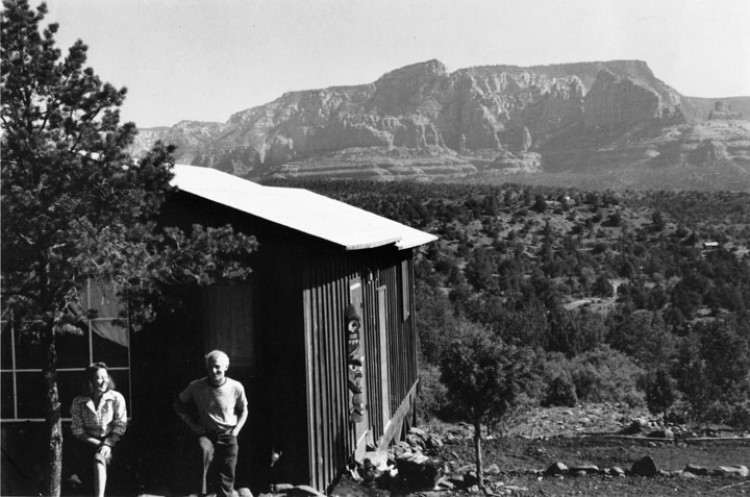

Max and Dorothea and their home in Sedona (1947)

Tanning and her husband Max Ernst lived in Sedona on and off from 1943 to 1957. They had constructed a three-room rough-hewn dwelling which Dorothea named Capricorn. It was a simple home which had no running water, a precious commodity which had to be hauled daily from a well five miles away. At the time Sedona was a small town with just a few hundred inhabitants. Dorothea lovingly described their house and living there in her autobiography:

“…Alone it stood, if not crooked at any rate somewhat rakish, stuck on a landscape of such stunning red and gold grandeur that its life could be only a matter of brevity, a beetle of brown boards and tarpaper roof waiting for metamorphosis………Up on its hill, bifurcating the winds and rather friendly with the stars that swayed over our outdoor table like chandeliers…”

Dorothea and Max with his outdoor sculpture “Capricorn” (1947)

Ernst had his own studio at the rear of the property whilst Dorothea painted in the house. In the summer of 1947, their home was connected to the mains water supply and to celebrate the arrival of water, Max Ernst, commemorated the moment with a large outdoor sculpture which Dorothea recalled in her autobiography:

“…In the summer of 1947, Max Ernst, exuberant and inspired by the arrival of water piped to our house (up to then we had hauled it from a well five miles away), began playing with cement and scrap iron with assists from box tops, eggshells, car springs, milk cartons and other detritus. The result: Capricorn, a monumental sculpture of regal but benign deities that consecrated our ‘garden’ and watched over its inhabitants…”

Capricorn, which refers to the tenth sign of the zodiac, is normally represented by a goat with a fish tail but Max Ernst divided Capricorn’s attributes between two figures, the horned male and the mermaid. The two main figures can be identified as a king and queen seated on their thrones. Ernst reportedly called Capricorn a family portrait, although his wife cast doubt on that. The couple did not have children together, but they did own two dogs, one of which may have inspired the animal in the king’s lap with its long tongue hanging out.

Capricorn by Max Ernst (cast in 1975)

The statue remained in Sedona but in Washington’s National Gallery of Art there is a large bronze replica of the sculpture.

………………………………to be concluded.

Fascinating to read and have the picture explained. Thank you