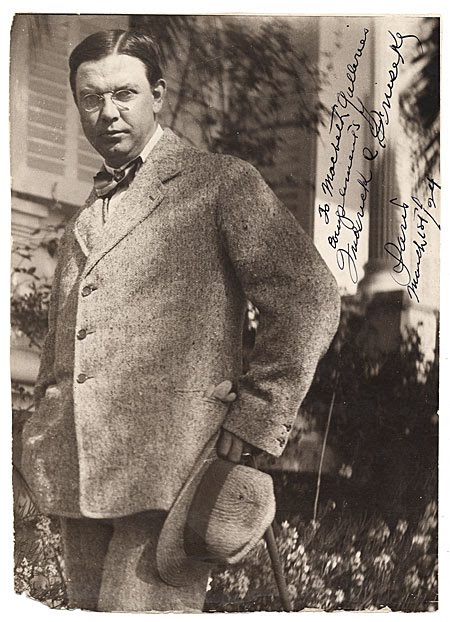

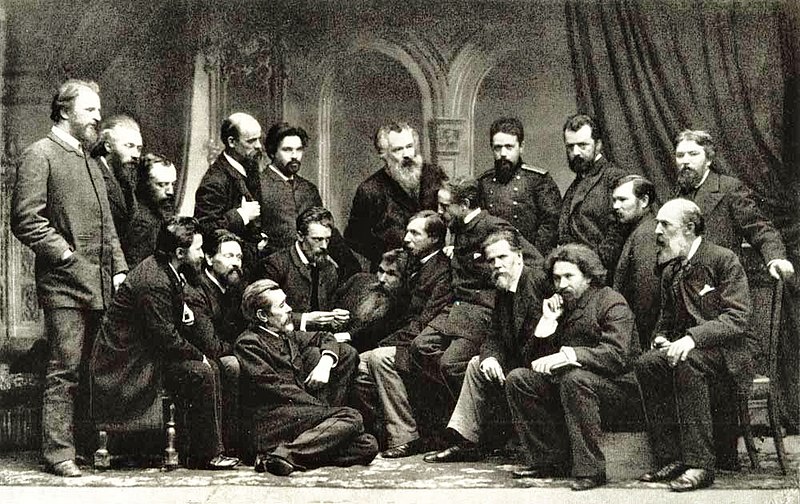

In the Spring of 1902, Frederick Frieseke was back in America after a five-year stint in France. His reason for returning to his country was two-fold. He wanted to take care of his American side of his career and probably more importantly he had come to be with his stepmother who was seriously ill. Once on American soil he wanted to have some of his artwork exhibited at two prestigious exhibitions – the Art Institute of Chicago and then the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Having exhibited in Paris at the Societe Nationale des Beaux-Arts and the Salon stood him in good stead. Frederick held a series of meetings with William R. French, director of the Art Institute of Chicago, which resulted in a special exhibition of eight of his paintings, which were hung together in Chicago’s annual exhibition.

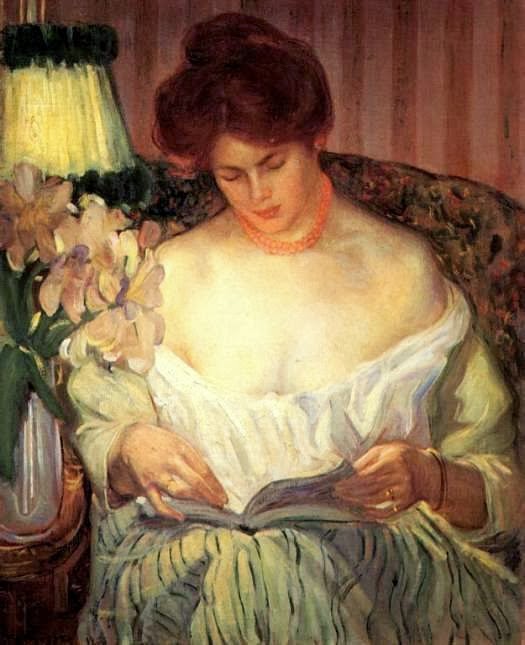

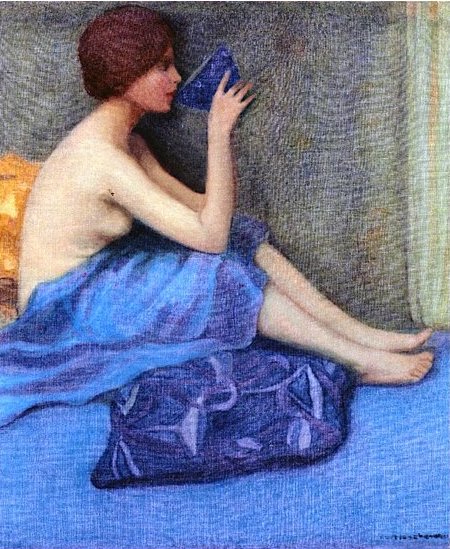

During the next seven months Frederick spent time in Owosso, transacted business in New York and Chicago, and was able to maintain his flow of drawings for Wanamaker, as well as visiting Sadie in New York. Frederick continued to paint whilst in Owosso and he employed a local young woman, Gertrude Hallowell to model for him. One such work was his painting, Gertrude, Girl with a Book, which he completed in 1902, featured Hallowell.

Another portrait featuring Hallowell was his painting entitled Femme lisant a cote d’line Inmpe (Woman Reading beside a Lamp) which he also completed that year.

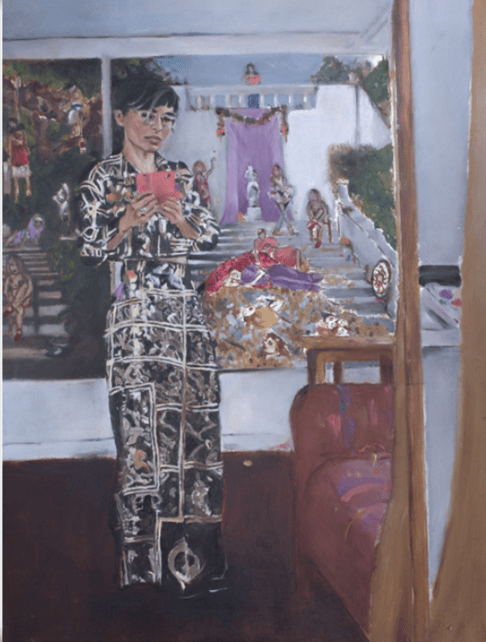

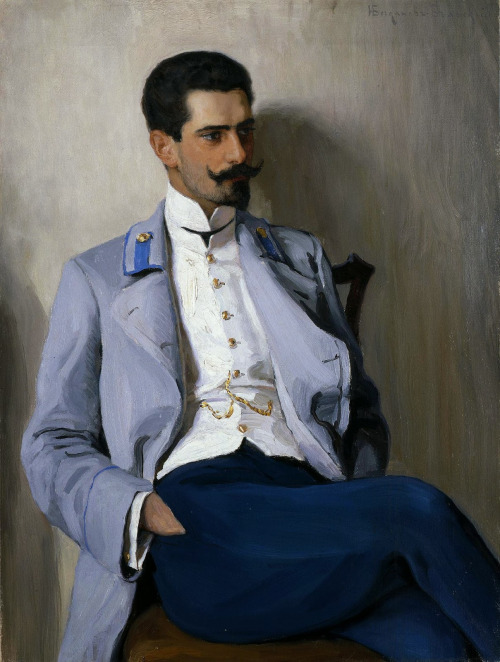

Frederick returned to Paris in November 1902 and moved into his new studio and apartment at 6, rue Victor Considerant, which was situated on the opposite side of the Place Denfert Rochereau. The rooms he rented were on the first floor above the apartment of the newly married Alson and Medora Clark, with whom he was to build up a great relationship with for the next few years. The couple were pleased to provide Frederick with a kind of domestic permanency and friendship. The three often shared meals and spent evenings together. Medora soon became Frederick’s model and posed for his 1904 painting entitled The Green Sash.

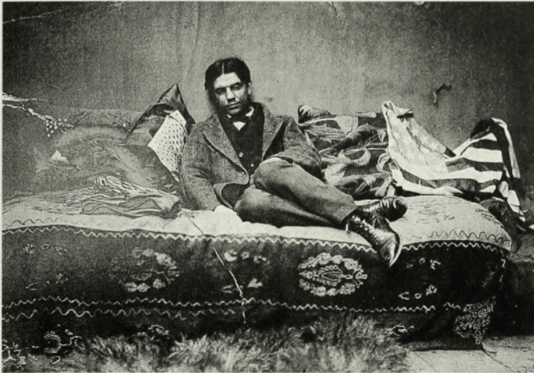

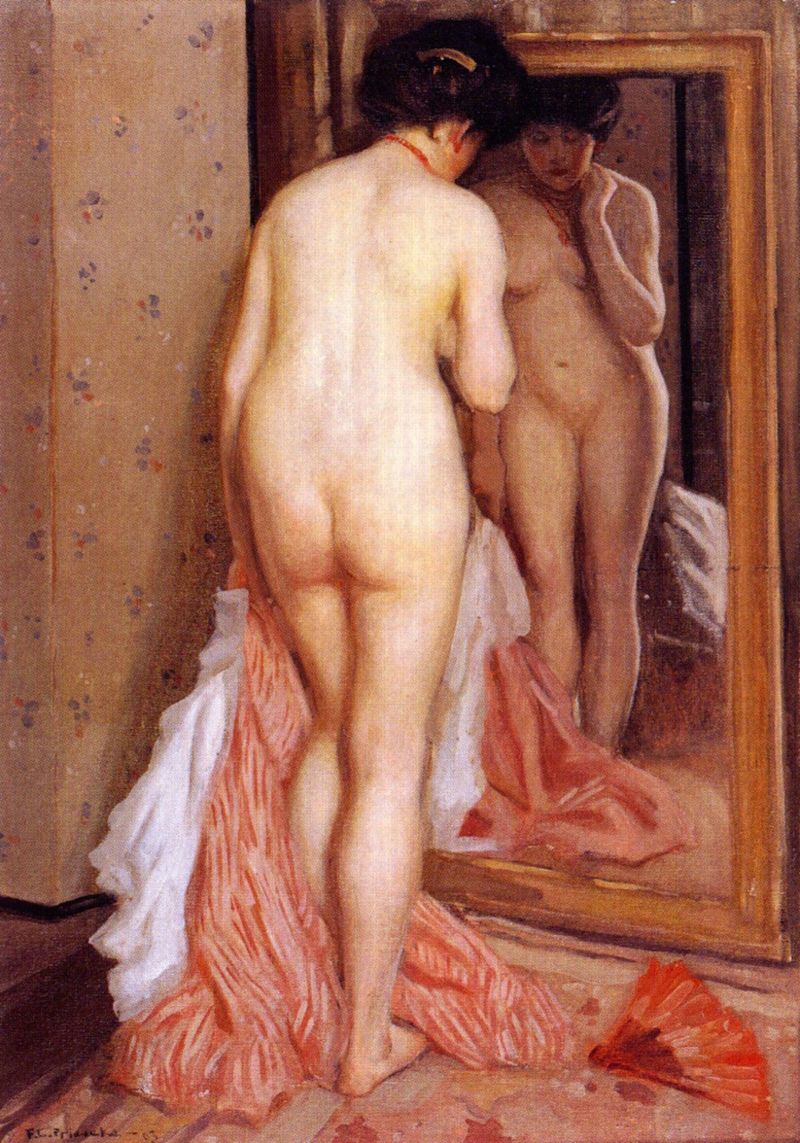

Fredeick Frieseke also engaged the services of a Parisian model, Jeanne Blazy, someone who had worked with the leading artists at the time. For Frederick she was not just his model, she was also a great help to him taking over some of his domestic chores. In a letter to Sadie Byers dated March 27th 1904, he wrote:

“…I’ve had a nice model. She’s as useful as anything in other things besides posing. Brings my things for luncheon and cooks them before she leaves, hunts up anything I wish and is always cheerful. Always late but works on as long as I wish. She has posed for Whistler and lots of the big men. Posed for MacMonnies’ statue in the Luxembourg…”

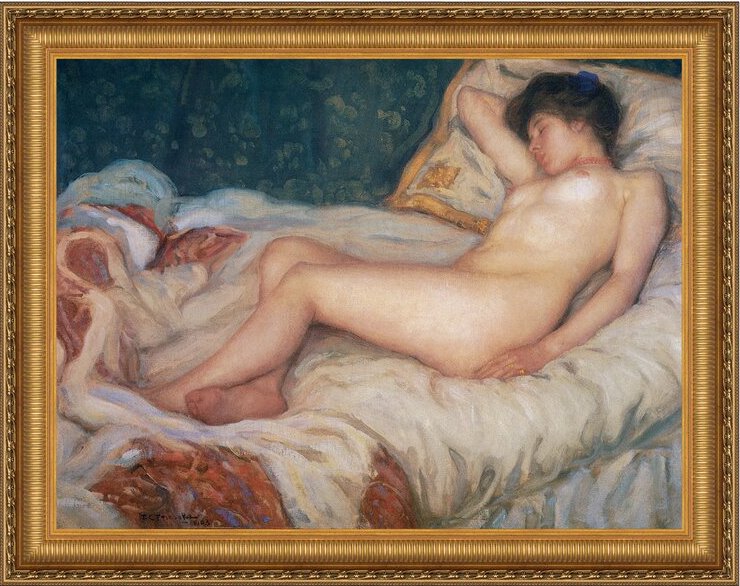

The bronze statue he wrote about was Bacchante with Infant Faun by the American sculptor William Frederick McMonnies’ 1894 work and it was Blazy’s talent of standing on one foot for a long time while balancing an infant on her arm, as she apparently did for MacMonnies’s Bacchante with Infant Faun. It was exhibited at the 1893 Salon of the Societe Nationale des Beaux-Arts and later purchased for the Luxembourg Museum. Frederick used Jeanne Blazy for his 1903 painting entitled Sleep.

Sadie O’Bryan and her family returned to Paris in October 1903 and took a small apartment at 206, boulevard Raspail. Just around the corner was the Dome, the cafe-restaurant where the American artists were often to be found and Frederick lived a short ten- minute walk away. Sadie’s father, Judge O’Bryan died suddenly on March 1st, 1904, following an operation for appendicitis. This meant that the family had to make a hasty return to America. Frederick had been with the family around the time of Sadie’s father’s death and decided to return to America with them. The family and Frederick left France on March 5th 1904 on the SS. Saint Paul and arrived in New York on March 13th and then travelled to Pittsburgh.

Frederick and Sadie were now apart once again. She in Pittsburgh with her family and he in New Jersey. They kept on with their correspondence and in one poignant letter he tried to console her. He wrote:

“…Yesterday morning I went to see Foote, and he was surprised enough to see me. Got me onto the floor and jumped on my—what one should keep covered—and we had a nice day together. It was horribly hard for me to leave you the other night. And when I came back for my umbrella and found you crying —dear me—I most disgraced us all by putting my arms around you. Dearie, the first days of your getting home are going to be hard ones for you all…”

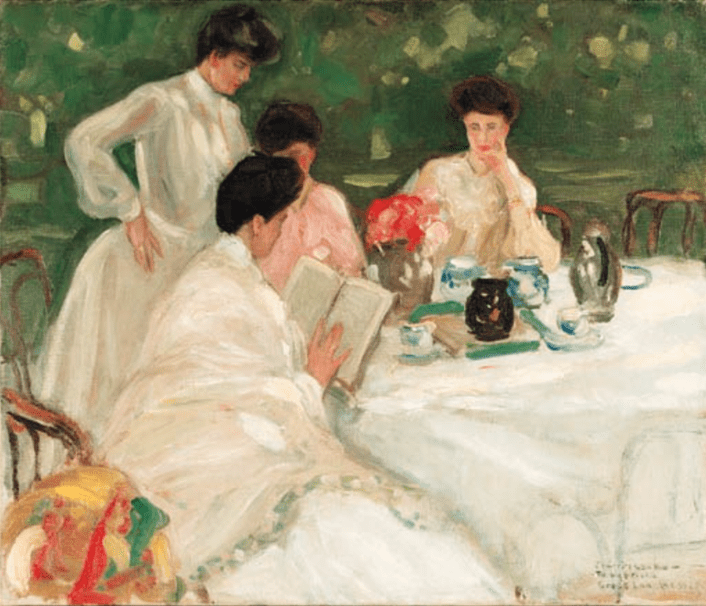

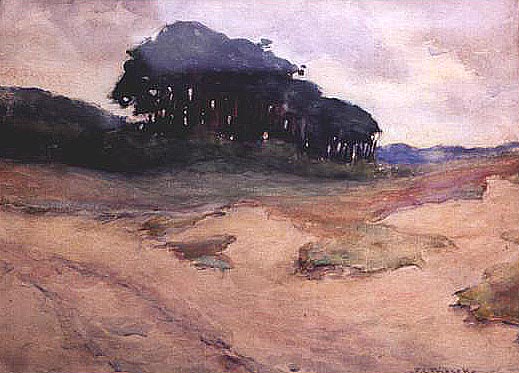

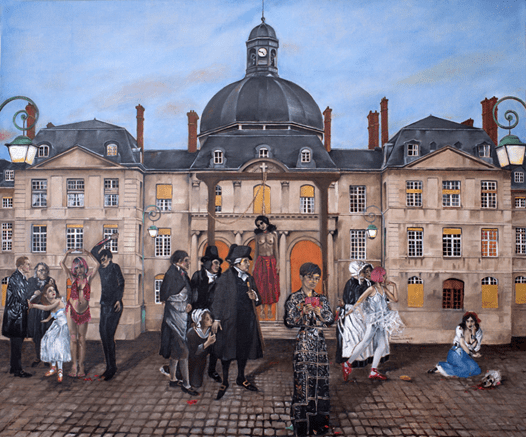

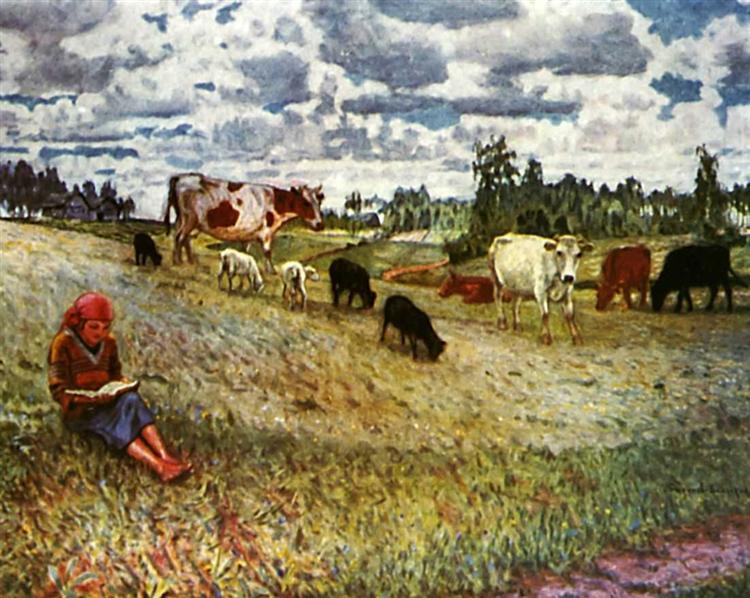

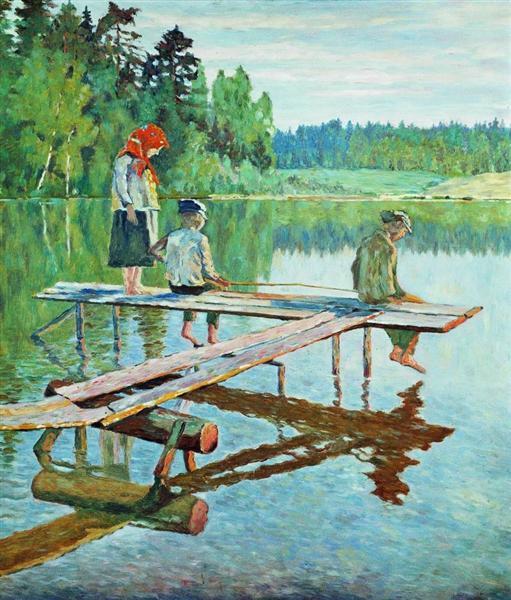

Frederick Frieseke had associated with a group of Americans artists and their partners, including the Clarks, who frequented the residence of Grace Lee Hess, at her house in Moret-sur-Loing, some fifty kilometres southeast of Paris, beyond Barbizon and Fontainebleau. It was here that Frederick and his friends celebrated the Fourth of July, and it was also here that Frederick executed his first large figure painting done plein air, Le Thé au Jardin (Tea in the Garden), featuring Grace Lee Hess and friends. This is a classic work in the Impressionist manner and a magnificent example of Frederick Carl Frieseke’s early style. His paintings completed between 1904 and 1919 epitomise his ambitious and important ventures into the world of Impressionism. It was the first true en plein air work that Frieseke painted and Le Thé au Jardin marks the most noteworthy turning point in the artist’s career.

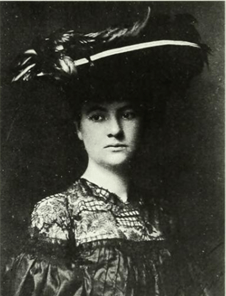

Frieseke had not only had Grace Lee Hess model for his large painting, Le Thé au Jardin but had also completed a portrait of her. Their relationship blossomed and may have given Hess thoughts of romance but Frederick, and even though he liked to be spoiled by Hess, was wary of this turn of events. It all came to a bitter end when Frederick announced his engagement to Sadie and in a letter to his betrothed, he talked about his rift with Grace Lee Hess:

“…It’s all over between Miss Hess and myself. She refuses to see me and insists that I’ve not acted honorably etc., which is very much too bad. And I’m sorry to lose her friendship but, well, I love Sadie very much and she loves me and while she may not be so keen at discovering my faults and correcting them—yet I think for that reason we will get along beautifully . . . and not quarrel as was the habit of Miss H and myself. At least I corrected the offenses and she did the quarrelling…”

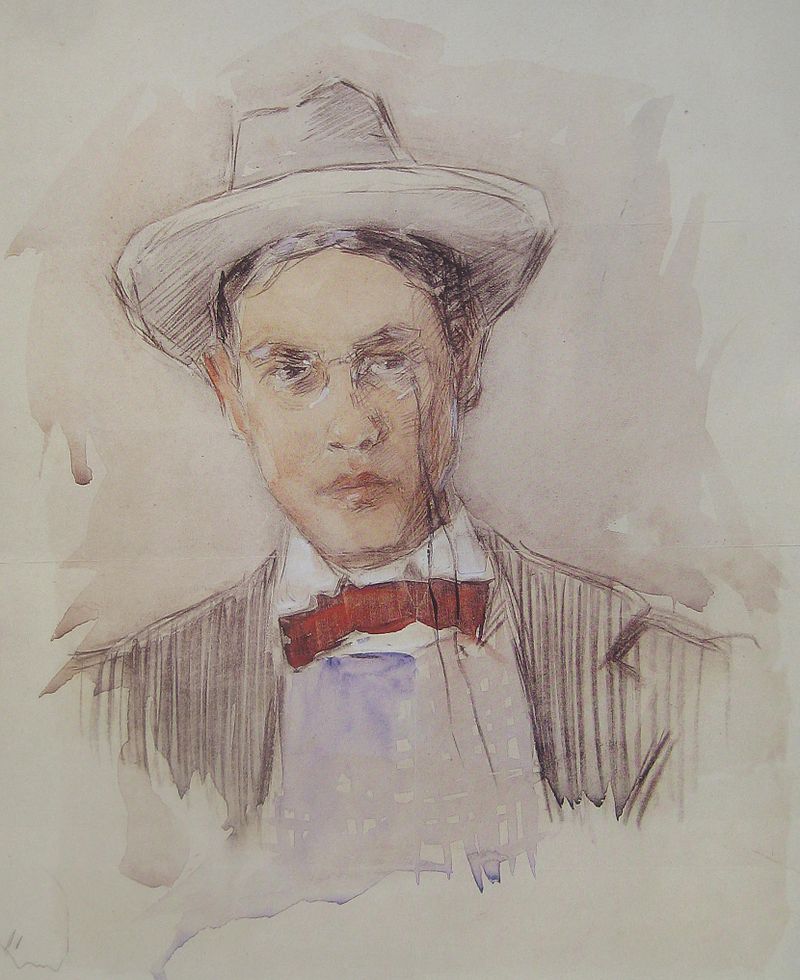

Frederick Frieseke and Sadie O’Bryan were finally married on June 27th 1905. In 1906 Frieseke completed a formal wedding portrait of his wife entitled Rest (Femme au sofa). This work, which appeared at the Salon that year, marked a new direction of Frieseke’s work. It was the start of what was to be many of his domestic depictions that would occupy him for the rest of his life – the embellishment of his intimate relationship he had with his wife and family.

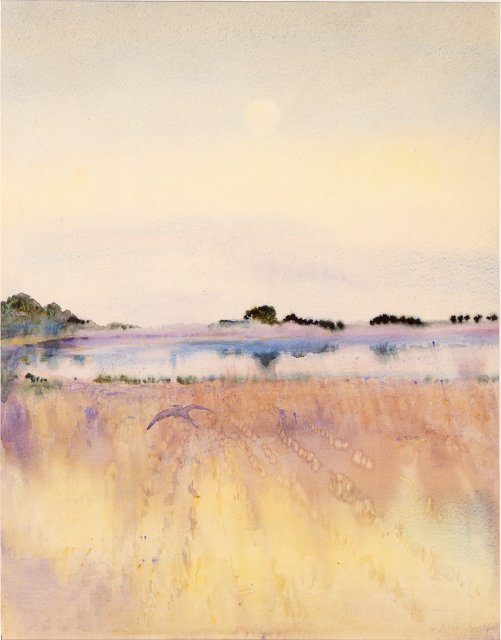

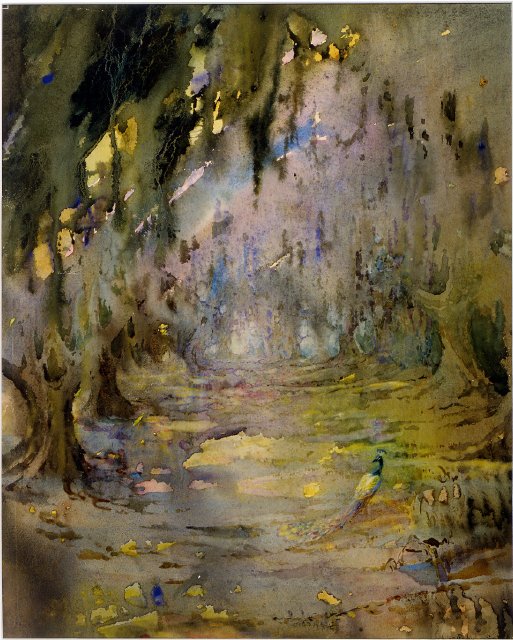

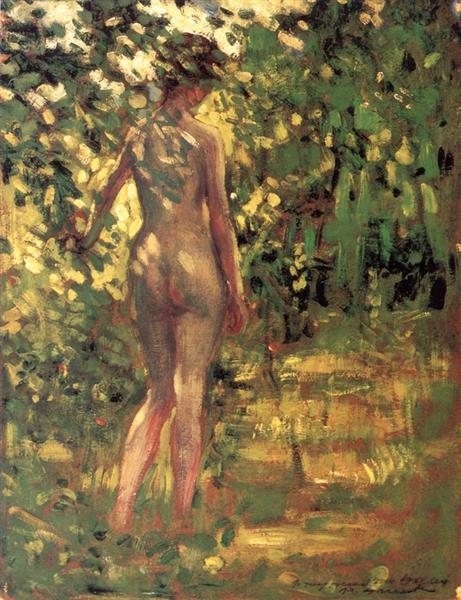

Beginning in 1906 they began to escape the cold smoky atmosphere of Paris and spend the warmer months in Giverny, which at the time was a small rural village fifty miles west of Paris on the right bank of the Seine as it runs towards the sea. At the time it was a well-established art colony which was popular with American artists who had crossed the Atlantic to further their artistic experience. It was not just a community that solely painted. It was a group of like-minded people who enjoyed socialising. The men would take time off to fish. There was also numerous evenings where they would listen to or play music. Days were often spent playing tennis at the courts of the nearby Hotel Baudy. Models were brought in from Paris and posed nude in the protected gardens. Often the artists would pose for each other. The Friesekes would often take tea with the Monets, who were neighbours and Monet and Sadie, who both loved gardening would spend hours deliberating on the proposed expansion of Monet’s garden, and the new bridge from which his water lily garden could be enjoyed.

…………………………………….to be continued.

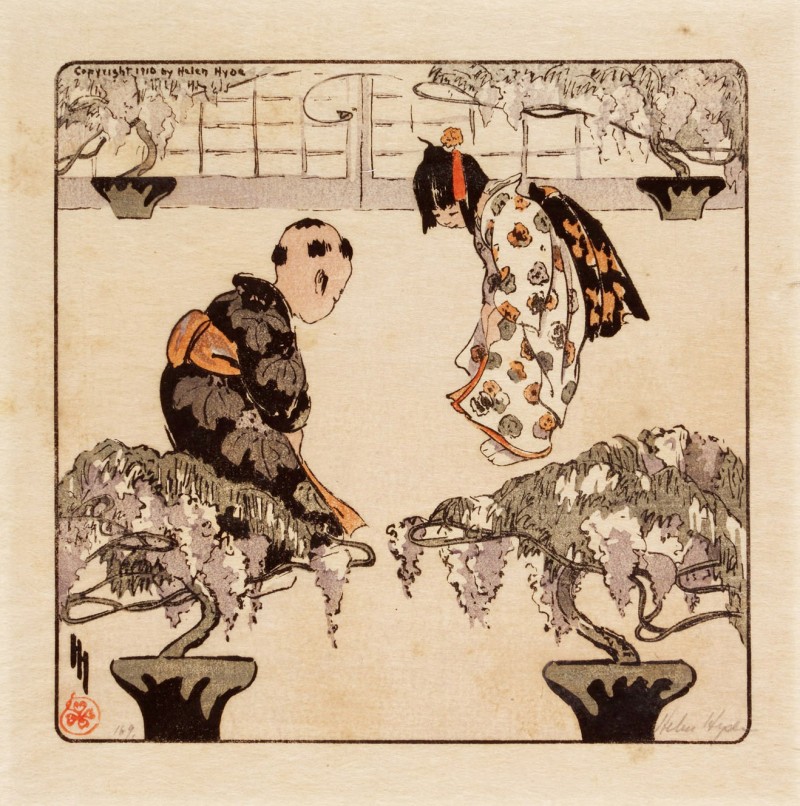

Woodblock Print by Helen Hyde

Woodblock Print by Helen Hyde