Violet Oakley

The second of the Red Rose Girls I am featuring is Violet Oakley. Oakley was the youngest of the Red Rose Girls, almost three years younger than Elizabeth Shippen Green and eleven years younger than Jessie Wilcox Smith. During the American Renaissance mural movement of the late nineteenth-century it produced one of the great female muralists – Violet Oakley.

Pennsylvania State Capital murals by Violet Oakley

Violet is probably best known for her murals at the Pennsylvania State Capitol. The paintings, done by Oakley, show scenes in the state’s history including Washington in Philadelphia in 1787 when the Constitution was written and Lincoln giving his address in Gettysburg in 1863. Yet, these were only a part of her extraordinary output. Over half a century, Violet Oakley decked out the interiors of churches, schools, civic buildings, and private residences with murals and stained glass. She also illustrated books, magazines, and newspapers, and painted hundreds of portraits. Her Renaissance spirit of civic responsibility helped shape the culture of Philadelphia.

Violet Oakley was born in New York on June 10th 1874, the youngest of three daughters of Arthur and Cornelia Oakley (née Swain) who had married in 1866. Violet’s eldest sister was Cornelia, who sadly died of diphtheria at the age of six after a very short illness, and a middle-sister, Hester. She and her family were brought up in Bergen Heights, New Jersey. As a youngster showing a love for art, she was brought up in the perfect family environment. In later life she quipped that her own interest in art was “hereditary and chronic” and that she had been born with a paintbrush in her mouth instead of a silver spoon. At least twelve of her ancestors were artists. Her paternal grandfather was George Oakley who came to America from London. He was a talented artist and made many return trips to Europe to study and copy many of the major works of art and became an Associate of the National Academy of Design. Violet’s father, Arthur, was taught to paint by his father but his business interests precluded him from making art his profession. Violet’s maternal grandfather, William Swain was a successful portrait artist and his daughter, Violet’s mother, Cornelia set up her own painting studio but gave up her artistic ambitions when she married. Other of Violet’s aunts, Juliana, and Isabel, became successful painters.

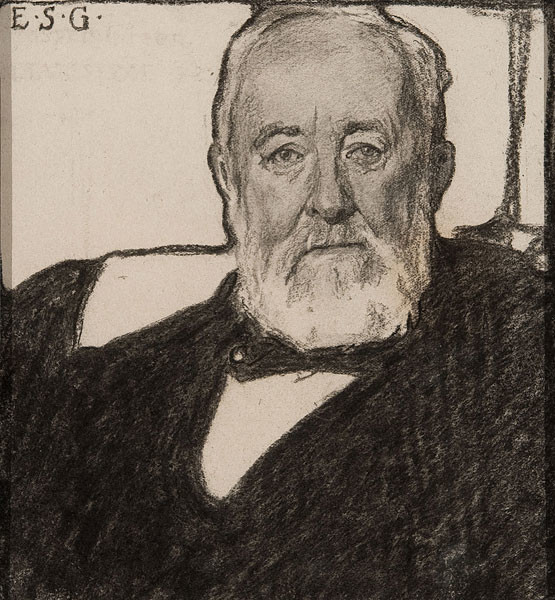

Violet was not a healthy child growing up as she suffered from asthma and an over-riding shyness. Having lost her eldest child Violet’s mother over-cossetted Violet continually worrying about her ill health and fearing that she may lose her second child. Her surviving sister, Hester, attended Vassar and Violet had hoped to follow her sister but her parents, ever concerned with their daughter’s health, decided to home-school her. She spent a lot of her time copying paintings by the Old Masters, the prints of which had been brought home by her two grandfathers from their European vacations. It was not until 1894, when Violet was twenty years of age, that the family allowed her to leave home to study. She travelled with her father to New York city to attend classes at the Art Student’s league where she studied with Irving Wiles, who would become one of the most successful portrait painters in the United States, and who drew illustrations for magazines such as Harper’s and Scribner’s. Another of her tutors was Carroll Beckwith, an American portrait, genre, and landscape painter.

During the winter of 1895, the Oakley family travelled to France to visit relatives and both Hester and Violet decided to improve their artistic skills by enrolling at the Académie de Montparnasse where they studied at the atelier of the Symbolist painter, Edmond Aman-Jean. It was an all-female studio and the students were a mix of those females who wanted to become professional artists and dilettantes who were merely bored with everyday life. Violet fell into the former category whilst her older sister Hester, who had yet to decide whether to become an artist or writer, belonged to the latter and used the experience at the atelier to study people, many of whom she incorporated into her 1898 novel, As Having Nothing. The family’s European holiday was cut short when Violet’s father took ill. It is thought that he suffered a nervous breakdown brought on by the failure of many of his business ventures. Their father’s financial demise focused the minds of Hester and Violet in that they needed to earn money to support themselves and their family. Hester managed to write and sell her novels and Violet decided that her art had to become financially viable. Her family moved to Philadelphia to get medical advice for her father and so when Violet arrived in the city, she decided to enrol on two courses at the Pennsylvania Academy. One was with Cecilia Beaux whose course was entitled Drawing and Painting from Head and focused on portraiture. She also enrolled in the Day Life Drawing Class; a course run by Joseph de Camp. However, art tuition cost money, add to that cost of materials and the commute to and from the Academy and Violet had now encountered financial problems.

It was her sister, Hester, who saved the day. Hester was continuing with writing her first novel and decided to enrol at the Drexel Institute where Howard Pyle, a writer and an illustrator was running an illustration class and Hester decided that he was just who she needed to teach her to become a novelist. Buoyed by this find, Hester rushed home to tell her sister of the opportunity and persuaded her to leave the Academy after just one term and enrol at the Institute. One could not just walk into to Howard Pyle’s course, one had to prove one’s worth and so Violet carefully organised her portfolio of work. Howard Pyle examined Violet Oakley’s portfolio and accepted her onto his course, agreeing to help her progress. Violet and Hester then set themselves up in a rented studio at 1523 Chestnut Street and their mother gave them some of the family’s furniture. The two young ladies may have been sisters but they were as different as chalk and cheese. Hester, the Vassar graduate, was outgoing, vivacious, and full of self-confidence whereas Violet was painfully shy and highly emotional and friends stated that she lacked a sense of humour.

That day in 1897 when Violet Oakley first walked into Howard Pyle’s illustration class she came face to face with the other two Red Rose Girls, Jessie Willcox Smith and Elizabeth Shippen Green ………………….

……………to be continued.

The information I used for my five blogs about the Red Rose Girls was mostly collected from the excellent book entitled The Red Rose Girls. An Uncommon Story of Art and Love by Alice A. Carter. I can highly recommend this biography. You will not be disappointed.

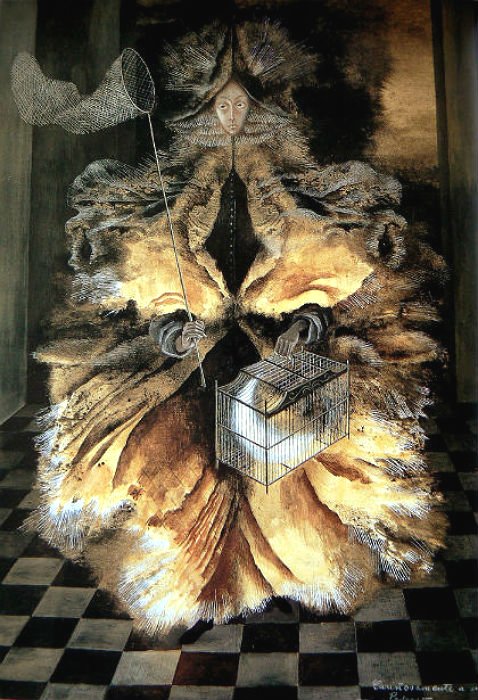

In 1958, Remedios Varo participated in the First Salon of Women’s Art at the Galerías Excelsior of Mexico, together with Leonora Carrington, Alice Rahon, Bridget Bate Tichenor and other contemporary women painters of her era. Remedios submitted two of her works, Harmony and Be Brief, and won the first prize of 3,000 pesos.

In 1958, Remedios Varo participated in the First Salon of Women’s Art at the Galerías Excelsior of Mexico, together with Leonora Carrington, Alice Rahon, Bridget Bate Tichenor and other contemporary women painters of her era. Remedios submitted two of her works, Harmony and Be Brief, and won the first prize of 3,000 pesos.

If you look closely at the chest cavity of the figure you will detect the circle of yin-yang, the Chinese symbol that similarly represents the balance of opposites. The face of the figure is one of calmness and serenity and suggests inner harmony and balance.

If you look closely at the chest cavity of the figure you will detect the circle of yin-yang, the Chinese symbol that similarly represents the balance of opposites. The face of the figure is one of calmness and serenity and suggests inner harmony and balance.

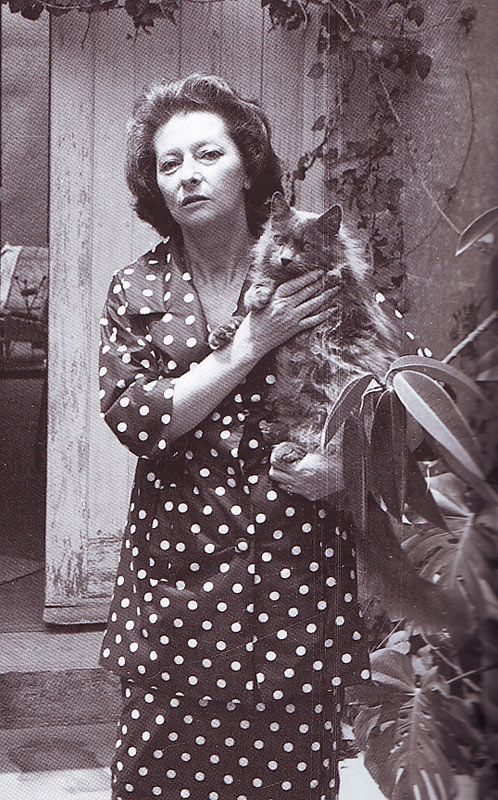

In 1963 Remedios suffered some health problems. She had complained of a shortage of breath when climbing stairs. She had a history of chronic gastric problems and was known to drink excessive amounts of coffee as well as being a heavy smoker. She was checked out for heart problems but was given a clean bill of health. The state of her mental health was open to doubt. Some of her friends said she was bubbly and full of life whist others said she had told them that she was depressed and did not know whether she could carry on with life. Walter Gruen, her husband, remembered the devastating afternoon of October 8th 1963, saying that he and Remedios had lunched with their friend Roger Cossio who had come to buy Varo’s painting, The Lovers. Gruen said his wife was happily explaining the details of the work to the buyer. With lunch over Cossio left and Gruen returned to his Sala Margolin shop across from their house to do some work. Shortly after, their Indian maid rushed into Gruen’s shop to tell him that Remedios was very ill. Gruen rushed home to find his wife complaining of chest pains. Gruen was unable to contact a doctor so left Remedios and went into the next room to consult some medical books. When he returned to his wife, he found that she had died.

In 1963 Remedios suffered some health problems. She had complained of a shortage of breath when climbing stairs. She had a history of chronic gastric problems and was known to drink excessive amounts of coffee as well as being a heavy smoker. She was checked out for heart problems but was given a clean bill of health. The state of her mental health was open to doubt. Some of her friends said she was bubbly and full of life whist others said she had told them that she was depressed and did not know whether she could carry on with life. Walter Gruen, her husband, remembered the devastating afternoon of October 8th 1963, saying that he and Remedios had lunched with their friend Roger Cossio who had come to buy Varo’s painting, The Lovers. Gruen said his wife was happily explaining the details of the work to the buyer. With lunch over Cossio left and Gruen returned to his Sala Margolin shop across from their house to do some work. Shortly after, their Indian maid rushed into Gruen’s shop to tell him that Remedios was very ill. Gruen rushed home to find his wife complaining of chest pains. Gruen was unable to contact a doctor so left Remedios and went into the next room to consult some medical books. When he returned to his wife, he found that she had died.

In her early days in Mexico, Remedios did few paintings and spent most of her time writing. She and Leonora Carrington would write fairy tales, collaborated on a play, invented Surrealistic potions and recipes, and influenced each other’s work. The two women, together with another of their friends, the photographer Kati Horna became known as “the three witches”

In her early days in Mexico, Remedios did few paintings and spent most of her time writing. She and Leonora Carrington would write fairy tales, collaborated on a play, invented Surrealistic potions and recipes, and influenced each other’s work. The two women, together with another of their friends, the photographer Kati Horna became known as “the three witches”