Today I am once again featuring a Victorian painter. His name is August Leopold Egg and he was born in London in 1816. He was the third son of Joseph and Ann Egg. His Swiss-born father, like his family before him, was a gunsmith and today one of his guns or rifles commands a high price at auction.

In 1834 Augustus studied art at the Sass Academy in London. Henry Sass was an English artist and teacher of painting who founded this London art school and it provided training for those seeking to enter the Royal Academy. Two years later, in 1836, the twenty-year old August Egg enrolled as a Probationer to the Royal Academy Schools. The following year, he joined up with a number of fellow aspiring artists and formed a sketching club, known as The Clique. This small grouping, which included the founder, Richard Dadd, also included Alfred Elmore, William Powell Frith, Henry Nelson O’Neil, John Phillip and Edward Matthew Ward. The Clique was characterised by its denunciation of academic high art in favour of the simpler genre painting, and the group were influenced by the great English narrative painter William Hogarth and the Scottish historical painter David Wilkie. For them, art was for public consumption and for the public to judge. They believed that works of art should not be judged solely on how well they conformed to academic principles.

August Egg was at pain to combine popularity with moral and social activism in his paintings which was similar to how his friend, the writer Charles Dickens managed to do with his novels. Egg and Dickens became great friends and jointly founded the “Guild of Literature and Art”, which was a philanthropic organisation which provided welfare payments to struggling artists and writers. Egg’s early works of art were mainly illustrations of literary subjects as well as historical incidents taken from the accounts of the seventeenth century diarist, Samuel Pepys. He also showed great interest in Hogarth’s narrative works, which often had a moral theme such as Marriage à la Mode and The Rake’s Progress and it was probably these works that inspired Egg to complete his moral narrative painting, The Life and Death of Buckingham. Many members of The Clique were vociferous critics of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood because, to them, their art was deliberately unconventional, but Egg disagreed and became a great friend and admirer of William Holman Hunt. In 1848 Egg completed his much lauded work entitled Queen Elizabeth discovers she is no longer young. This won him critical acclaim and earned him the position of Associate Member of the Royal Academy (ARA). In 1860 he was elected to the position of Royal Academician (RA). That same year he married Esther Mary Brown.

August Egg was, besides being a talented artist, a great organiser and spent a much of his time organising exhibitions for his fellow artists. In 1857 he was one of the organisers of the The Art Treasures of Great Britain exhibition, which was held in Manchester from May to October of that year. To this day, it is said to remain the largest art exhibition ever to be held in the Great Britain, possibly in the world with over 16,000 works on display. It was so popular that it attracted over 1.3 million visitors in the 142 days it was open, which at the time, was about four times the population of Manchester.

Egg loved the theatre and it was through this love that he became friends Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins and at times they would all take part in amateur theatricals. In 1849, Egg was elected to the Garrick Club, a gentleman’s club, which was named after the well-known thespian of the time David Garrick. At the end of that year, Egg who often travelled extensively around the Mediterranean countries, set off on a journey to Switzerland and Italy and was accompanied by Dickens, who had just completed his novel Bleak House, and his other writer friend, Wilkie Collins. Egg’s health was never good and in his later years he tried to remedy this by living in the warmer climates of the Mediterranean countries. He died in Algiers in 1863 of asthma aged 46. He was always well loved and his friend, Charles Dickens, described him as:

“….always sweet-tempered, humorous, conscientious, thoroughly good, and thoroughly beloved…”

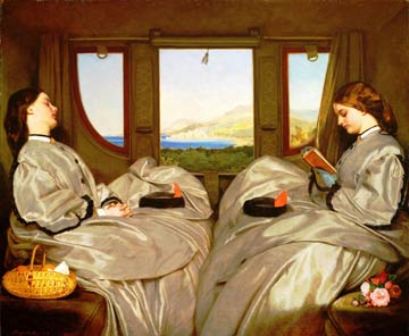

My featured painting today by August Egg is entitled Travelling Companions which he completed in 1862 and can now be found at the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery. This has a connection with Egg’s travels as the setting of the painting is a railway carriage and through the open window of the carriage one can just make out the shoreline of Menton, a popular health resort in Victorian days, which lies close to Monte Carlo on the French Riviera. Look how the artist has cleverly depicted the motion of the carriage by painting the tassel attached to the window blind at an angle away from the vertical. There are no other people in the carriage besides the two females which may have been an indication that in those days, males and females rode in segregated train carriages. There is almost a perfect symmetry about the women in this painting as they sit across from each other in the carriage. They wear almost identical billowing voluminous grey dresses. Their hats rest on their laps. Their faces are each framed with a mass of beautiful brunette hair and each wears a black choker around their neck. At first glance, they almost look like mirror images of each other but once we look more closely, there are obvious differences. One sits with a basket of fruit by her side, whilst the other has a bouquet of flowers next to her. One reads whilst the other lays back with her eyes closed. There is no interaction between the two females. Neither seems to be interested in the other or what sights can be seen from the carriage window. Did August Egg want us to take the painting on face value, that is, did he want us to just to accept that this is simply a painting of two women travelling in a railway carriage? I did, but many do not see the painting in such simplistic terms. Maybe it is because Egg had painted many moral narrative works that people looked for hidden meanings in this work. I am not convinced, but let us look at some of the suggestions that have been put forward about how we should interpret what we are looking at and then I will let you be the judge as whether they are too fanciful to believe or there is a modicum of truth in what they want us to accept as the true meaning behind the painting.

So, if you, like me, look on the painting as simply a depiction of two women travelling by train let me “muddy the waters” for the more I investigate this painting the more I am wondering whether I am missing something. Is this simply a painting of two almost identical women on holiday travelling in a railway carriage? Are we simply observing a young lady sleeping and a young lady reading? First of all, are we looking at two separate women? That would seem a silly question but some people would have us believe they are one and the same person and that the artist is portraying them in different moods. Some again who believe in the “one woman” theory would have us believe that perhaps the waking woman is the product of the sleeping one: in other words, she is the dreamed projection of the other. Another theory is that the one who sleeps is a portrait of inactivity and the one who reads is a portrait of activity – a pictorial depiction of “Industry and Idleness”. I also read that Egg’s painting was a statement of past and future with the one woman with her eyes closed dreaming of the future whilst the other reads of the past?

And so the theories about the interpretation of this painting mount up but I suppose one has to remember that in Victorian times, tales with a moral were all the rage and Augustus Egg painted many pictures which told a moral tale, so is this yet another one?

For people who like to add their own interpretation to a painting many feel the need to explore the sexual connotations in a scene and I read an article which does just that. It is by far the most unusual interpretation (I initially intended to say “fanciful interpretation” of the painting but decided the word “fanciful” sounded derogatory and that is not my intention). The article I came across was on the website entitled Victorian Visual Culture and was written by Erika Franck as part of a degree course in Modern Literary studies. She wrote:

“…Although Egg’s Travelling Companions (1862) is considered to be a reflection on railway travel and the way in which the different classes were segregated, one cannot ignore the sexual connotations that are evident in the painting. The painting displays two young ladies who appear to be identical, and yet upon closer inspection are not. It seems as though the girl on the left has been awakened sexually despite the fact that she is asleep. This can only be detected in comparison with the girl on the right. Firstly, the young lady on the right has flowers set beside her as opposed to the other lady who has a basket of fruit. The flowers convey the virginity and sexual virtue of the girl on the right whereas the fruit beside the girl on the left implies her virginity has been lost and her innocence has been replaced by sexual indulgence and consequently sexual maturity. This analogy continues as one studies the way in which the companion on the right has the curtain slightly drawn to shade her from the sunlight, as opposed to the lady on the left whose curtain allows the light to expose her fully. In addition, the companion on the left has removed her gloves and is thus further exposed physically. The hat of the lady on the left is positioned slightly to the left in contrast to her companion whose hat sits centrally upon her lap. Again it appears as though the girl on the left has exposed herself sexually in that she is less guarded than her sister. This notion is furthered when one considers the posture of the two companions. The one on the right seems more composed and is reading a book whereas the one on the left is leaning back exposing her neck, and is asleep. Although one could question that if this girl has been awoken sexually then why is she the one who is sleeping in the painting? However, it is possible to argue that this displays her overall lack of constraint and propriety that is portrayed by the other young lady. Even the hair of the companion on the left seems to have fallen out compared to the girl on the right whose hair is pinned back in a controlled manner. If one examines the shape of the carriage window in conjunction with the symmetry of the girls’ dresses one can observe there is a shape which resembles that of a chalice. This traditionally symbolizes the womb and fertility, thus accentuating the theme of sexual awakening. Therefore, Egg presents a young woman who appears to be sexually passive and another who is not. One can speculate that the two ladies are the same person and this consequently, would indicate that a transition from sexual unconsciousness to sexual enlightenment has occurred. However, if one is to argue that this picture depicts a girl who has fallen sexually in contrast to her companion, then this painting serves as a mere “freeze-frame”. It does not represent the consequences of the girl’s fall….”

I sometimes wonder whether I should write a book entitled My Interpretation of Great Paintings as I would be simply just one of many to offer an interpretation as to what I think we are looking at and as the artist is dead and cannot repudiate my suggestions, who is to say the hidden meanings I put forward are wrong ! Somebody once told me that if you want to write a successful biography of an artist you have to come up with at least one amazing, contentious even bizarre fact about the artist that nobody has ever heard before as that will get you the publicity needed to sell the book. I wonder if the people who have interpreted Egg’s work were thinking along those lines !