In my last blog I looked at the early life of Gabriel Metsu and had reached the year 1651, the year in which his mother died. Gabriel Metsu was twenty-one years of age and, as such, was still not looked upon as an adult. In the Netherlands at that time, adult status was only reached when a person became twenty-five years of age, and for that reason Gabriel came under the guardianship of Cornelis Jansz. and Jacob Jansz. de Haes. Around this time it is thought that he was advised by a fellow aspiring artist, Jan Steen, to seek employment as an apprentice with Nicolaus Knupfer, a painter from Utrecht. Metsu remained with Knupfer for a few years during which time he completed a number of religious paintings.

In 1654, his guardianship came to an end and his late mother’s estate was finally settled and Gabriel received an inheritance. With this newly found wealth, Metsu left Leiden and moved to Amsterdam where he had enough money to set up a workshop in a small house off the Prinsengracht. He remained there for a short time before moving to a canal-side residence. It is believed the reason he moved was that he had got into so many arguments with his neighbours for keeping chickens at the rear of his house.

His desire to move to Amsterdam was probably due to his search for artistic commissions as the city had far more opportunities for an artist than that of the smaller town of Leiden. The other thing that Metsu realised when he arrived in Amsterdam was that small-scale genre scenes were far more popular with art buyers than large scale religious works and so he made a conscious decision to change his painting style and for his inspiration into that art genre, he could study the works of the Leiden painter, Gerard Dou and the Deventer artist Ter Borch. Metsu’s favourite subjects became young women, often maids, drinking with clients and engaged in domestic work often in tavern settings.

In May 1658 Gabriel Metsu married Isabella de Wolff who came from Enkhuizen. Her father was a potter and her mother, Maria de Grebber, was a painter and came from a family of well-known artists. Metsu had probably met Isabella through his connection with the de Grebber family when he was a teenager. Anthonie de Grebber, who had given Metsu some early artistic training in those days, was a witness to Metsu and Isabella’s pre-wedding settlement. They married voor schepenen which means “before magistrates” which presumably meant that the couple did not belong to the Dutch Reformed Church and it is thought more likely that they were both Catholics. Isabella became one of Metsu’s favourite models and appeared in many of his works. In 1663 he completed a work featuring his wife, Isabella, as the model for Saint Cecilia. She is seated playing the viola da gamba. St Cecilia was a Catholic martyr who was revered for her faithfulness to her husband (note the lap dog) and it could be that Metsu by having his wife model for the martyr was his way of publicly recognising his wife’s fidelity. This would not have been the first time an artist had used his wife in a depiction of this Catholic saint as in 1633 Rubens completed a painting of St Cecilia in which he used his second wife, Hélène Fourmen,t as the model. It is entirely possible that Metsu had seen the Rubens’ painting and then decided to use Isabella for his depiction of the martyr.

Gabriel Metsu died in October 1667, just a few months before his thirty-eighth birthday and was buried in the Nieuwe Kerk in Amsterdam. Following the death of her husband Isabella moved back to Enkhuizen to live with her mother, where she died in her late eighties.

Another painting by Metsu, featuring his wife as an artist, was entitled A Woman Artist, (Le Corset Rouge) and is dated 1661-4. So is this just simply a painting of an artist for which his wife modeled? Maybe not, for one must remember that Isabella was actually an artist in her own right, having been trained as an artist by her mother, Maria de Grebber, who had come from a family of artists and so this painting by Metsu may just be a loving portrait of his wife, highlighting her talent as a painter.

Do you ever re-read a book or watch the same film more than once? Many people who do tell of how they saw things in the film or read things in the book the second or third time which they had not picked up the first time and that for them was the joy for re-visiting the work. Genre works have the same effect on me. The more times I study them, the more new things I discover which were not apparent during my initial viewing. I also like the fact that often one cannot take things depicted at face value as there is often a hint of symbolism with the iconography of some of the objects that are dotted around the work and this I find utterly fascinating. I read art historians’ views on such things and often wonder whether what the artist has added to the work is as symbolic as the historians would have us believe.

In my previous blog about Metsu I talked about certain iconography in the painting entitled Woman Reading a Letter, and was rather scornful with regards the supposed sexual connotation of the abandoned shoe which was prominently depicted lying on the floor. In my next two featured paintings there is more iconography that has a supposed sexual nuance. In the next two featured works we see a dead bird being offered to a woman. Just a mere offering of food? Maybe not for the Dutch word for bird is vogel and in the seventeenth century the word was synonymous with “phallus” and the Dutch word vogelen, which literally means “to bird”, was slang for “to have sexual intercourse with”. So when we look at the two paintings we should look at the offer of a bird not as a gift of food but an enticement to have sexual intercourse!

In the Wallace Collection in London there is a magnificent painting by Metsu entitled The Sleeping Sportsman which he completed between 1658 and 1661. It is a kind of “hunter’s scene” and it was in this painting that we need to think laterally in as much as the hunt is the gentleman’s hunt of a woman. In this painting by Metsu the setting is the outside of a tavern. A hunter has called in for a drink after a long day’s shooting. His gun is propped against a low wall and the two birds he has shot are on view, a pheasant atop the wall and another bird, probably a fowl, is seen hanging from the tree. Metsu has depicted a lady coming out of the inn with a glass and a jug of alcohol which has presumably been ordered by the hunter-sportsman. It would appear that the jug she brings him is not his first, as he has passed out from overindulging, and we observe an empty jug lying at his feet. After a day of hunting game he has decided to end it with a few drinks and search for the company of a female or as the French would say cherchez la femme, but, sadly for him, alcohol has won the day. Take a careful look at the stupefied hunter. It is supposedly a self-portrait of the artist. He lies slumped against the end of a bench, clay pipe in his lap lying loosely against his genitals which could be interpreted as the drunken state he is in has made him temporarily impotent. On the floor we see the remnants of another pipe which he must have dropped. Although finely dressed he looks a mess with one of his red gaiters sagging down his leg.

However, if we look again at the woman who is bringing the hunter’s refreshment, we notice that she is not looking at her “customer”, but her eyes are fixed on the man to the right of the painting who is hanging out of the window of the inn. He looks knowingly out at us. He is about to take the hunter’s bird from the tree and if we go back to the slang meaning of bird then he may also be also about to take the woman away from the comatose hunter. On the floor at the feet of the hunter is his hunting dog. He even looks meaningfully at us, its tail wagging, as if it too sees the funny side of the incident. It is a painting with a moral, warning us of the consequences of inebriation. Moralistic paintings were very fashionable and popular at the time in the Netherlands.

Gabriel Metsu painted a similar work around the same time entitled The Hunter’s Present. In this work we see a woman in a white dress with a red frock coat trimmed with ermine, again like the female in Woman Reading a Letter, ermine, being expensive, signified the wealth of the wearer. The lady is sitting demurely on a chair with a cushion on her lap as an aid to her sewing. She looks to her left at the dead bird the huntsman is offering her. In this depiction, the hunter is sober. Now that we know about the bird/vogelen/sexual intercourse implications then we are now also aware what the man maybe “hunting” for. If we look at the cupboard, behind the lady, we see the statue of Cupid, the God of Love, which gives us another hint that “love is in the air”. Standing by his master’s side, with its head faithfully on his lap, is a similar spaniel hunting dog we saw in the previous painting. There are also another couple of additional items of symbolism incorporated in the work, besides the bird offering, that I should draw to your attention. Look on the floor in front of the woman. Here again we have the abandoned shoe or slipper and although I was sceptical in my last blog as to its sexual meaning I am starting to believe that it has a symbolic sexual connotation. So is the woman, because of the abandoned slipper, to be looked upon as a sexually permissive female. Maybe to counter that argument we should look at her right arm which rests on the table and there, by it, we see a small lap dog, which is staring at the hunter’s dog. Lap dogs have always been looked upon as a symbol of faithfulness. So maybe the woman is not as wanton as we would first have believed. Maybe the hunter is not some unknown man, chancing his luck, but it is a man known to her, maybe her lover and so perhaps the bird symbolism in this case should be looked upon as just a prelude to lovers making love rather than a more sordid prelude – vogelen! .

The third and final painting by Gabriel Metsu I am featuring is by far one of his most sentimental and poignant. It is entitled The Sick Child and was completed in the early 1660’s. Netherlands, like most of Europe had been devastated by the bubonic plague. Amsterdam was ravaged in 1663–1664, with the death toll believed to be as many as 50,000, killing one in ten citizens and Metsu would have been well aware of the heartbreak and suffering felt by people who had lost their loved ones.

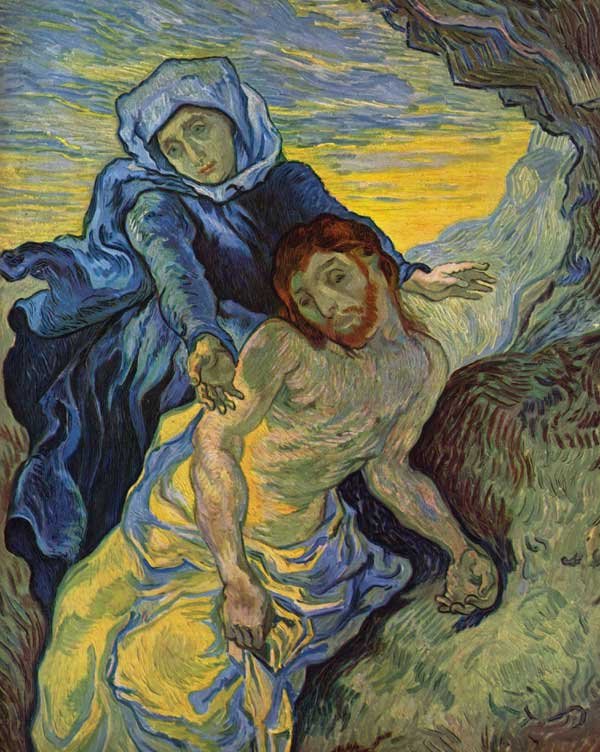

The painting has a dull grey background and the lack of background colour ensures that we are not distracted away from the two main characters. There is a religious feel about this work. The reasons for this assertion are threefold. Firstly the positioning of the mother and child is very evocative of the Pietà, the portrayal of the Virgin Mary holding her son’s lifeless body in her lap, as seen in Italian Renaissance art. Secondly, the mother is depicted wearing a grey shirt and, as a working woman with a child, one would also expect this but one would have expected her to be also wearing a plain coloured dress but in fact Metsu has depicted her in a royal blue skirt with a red undergarment and these are the colours of the clothes one associates with Italian Renaissance paintings depicting the Virgin Mary.

Finally on the wall we see Metsu has added a painting of the crucifixion. These three factors go to show that Metsu consciously asks us to compare the circumstances of the Virgin Mary and her dead son with that of this mother and very ill child. The child, who is drooped in her mother’s lap, looks very ill and this is further underlined by the way the artist has painted her face. It is pallid and has a deathly blue tinge to it. The child’s legs fall lifelessly over her mother’s knees.

Tragically, Metsu died very young, at the age of thirty-seven. He was one of the most popular painters of his era and his paintings fetched high prices. Many art historians believe Metsu was one of the greatest of the Dutch Golden Age genre artists and that a number of his paintings were the best of their time. As I said earlier, although Vermeer is now one of the best loved seventeenth century Dutch painters, in the 18th and 19th centuries, Metsu was far more popular than him, and often Vermeer’s works were attributed to Metsu so that they would sell. Through Metsu’s works we can get a feel for everyday Dutch seventeenth life. His earlier genre works focused on the common man and woman but in the 1660’s he concentrated on scenes featuring the better-off Dutch folk, like the letter writer and his beau, and these are the paintings I have focused on in my two blogs featuring Gabriel Metsu.