Today I am concluding my look at the life of Thomas Fearnley and for those of you have just landed on this page, my introduction to the Norwegian artist’s life was the subject for My Daily Art Display blog of November 24th.

The date is 1832 and that September, Fearnley, who along with his fellow artists, the Dane, William Bendz and the German painter Joseph Petzl, had just left the Bavarian Alpine village of Ramsau and were beginning their long and strenuous trek on foot over the Alps to Italy. So why had this Norwegian artist and his friends set off on this gruelling journey? Why did Fearnley spent most of his life wandering around Europe? The answer probably lies in the fact that although the Norwegian landscape offered many beautiful vistas to paint, there were few commissions to be had from wealthy patrons in his native Norway. Whereas in the art capitals of Europe such as Paris, London, Rome and Munich there were a large number of affluent patrons who would pay generous sums for landscape works.

Fearnley and his travelling companions headed for Rome but first stopped off in Venice in the late October of 1832. The three travellers split up at this point as Fearnley was determined to carry on until he reached the Italian capital whereas Bendz wanted to stay in Venice. As I told you in my last blog, William Bendz took ill in Venice but left the city and went to Vicenza where his health deteriorated rapidly and he died of typhoid, just ten days after he had parted from his friends. Fearnley finally arrived in Rome in November 1832, just before his 30th birthday. He settled down in the Italian capital, living amongst the Danish and German artistic community. Fearnley made Rome his base for the next three years but was constantly setting off from there on his artistic trips. In 1883, along with a Danish friend, he left the capital on a long walking tour of Sicily and on his way back to Rome, visited Naples, Sorrento and Capri. This journey along the Amalfi coast had been carried out by his erstwhile mentor John Christian Dahl, ten years earlier.

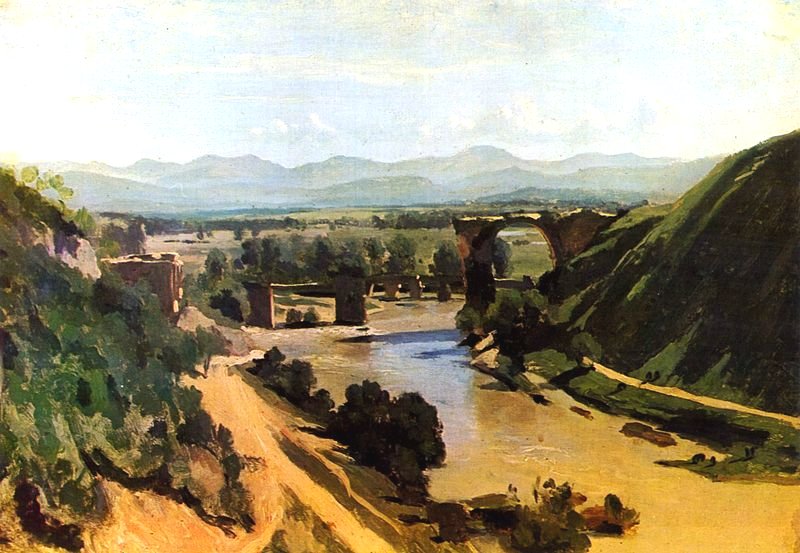

Fearnley loved the practice of en plein air oil sketching and he followed earlier practitioners of this kind of art such as Claude-Joseph Vernet, Pierre-Henri Valenciennes and the Welsh artist Richard Wilson, all of whom had pioneered en plein air sketching whilst they were based in Rome. The other aspect of this art, which Fearnley believed in, was to select views for painting that were “fresh”, even unorthodox rather than painting views which had been done so many times over by other landscape artists. Another aspect of art which fascinated Fearnley was how various meteorological conditions affected the light and the view of the landscapes. He strived for a true depiction of the skies and the cloud formations and was only too aware of the fast change in what he was looking at, due to varying changes in the weather conditions. Having left the colder, duller and wetter climate of Northern Europe and Scandinavia he was now able to appreciate and take advantage of the warmer, sunnier climes of Italy which allowed him a greater opportunity to paint outdoors for lengthy periods of time.

In 1835, after his three year sojourn in Italy, Fearnley decided to move on. He travelled north via Florence to Switzerland where he spent most of the summer studying the breathtaking Alpine scenery and especially the glaciers at Grindelwald, which would be depicted in his famous 1838 large studio oil painting entitled The Grindelwald Glacier, which is My Daily Art Display’s featured painting today. From this Alpine area he once again moves north, crossing the Alps, heading for Paris, arriving in September of that year. Whilst in Paris, he exhibits three of his works, including the “yet to be completed” Grindelwald Glacier painting. During Fearnley’s stay in Rome he had met and befriended a number of wealthy English art lovers. Many were rich aristocrats who were taking part in the Grand Tour. It could have been this that made him decide to travel from Paris to London in the spring of 1836. Whilst in the English capital, Fearnley took in the Royal Academy May Exhibition and at this exhibition he would have seen major works by the likes of Turner, Constable, David Wilkie and William Etty. However the artist who most impressed Fearnley was the English landscape painter Augustus Wall Callcott. This R.A. Exhibition was a special one as there were more than 1200 paintings being exhibited and it was the last one to be held at Somerset House. Whilst in England Fearnley made a number of painting trips and in August 1837 he, along with his fellow artist friend, Charles West Cope, visited the Lake District. He visited Derwentwater, Coniston and Patterdale, all the time recording the views in oil sketches. In 1838 Fearnley became the founder member of the Etching Club, an artists’ society founded in London. The club published illustrated editions of works by authors such as Oliver Goldsmith, Shakespeare, and Milton. Other well known artists who became members of this club were the Pre-Raphaelite painters, William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais.

In 1838, Fearnley exhibited his now completed work The Grindelwald Glacier at the Royal Academy. His wanderlust continued unabated and he leaves London in the summer for Germany. He first visits Berlin and then on to Dresden where he once again meets up with his former mentor and teacher J C Dahl. He makes a brief stop-over in Switzerland before returning to his homeland, Norway, where he lives in the capital Christiania for the next two years. Fearnley became a member of the Christiania Art Society. On July 15th 1840, he married Cecilia Catharine Andresen, the daughter of one of his patrons from previous years, the banker and Member of Parliament Nicolai Andresen. In the autumn the couple went to Amsterdam, where they stayed for one year, and where their only child, a son Thomas, was born. During their stay Fearnley becomes infected with typhus and on January 16th 1842 he died, aged just 39 years old. He was buried in a Munich cemetery but 80 years later his son took the initiative to have his father’s remains brought back to Norway, and in 1922 the tomb was moved to Our Saviour’s Cemetery in Oslo.

Fearnley’s painting, which at the time was entitled The Upper Grindelwald Glacier, Canton Berne, Switzerland, was started in 1836 and although not finished was shown at the Paris Salon that year. It was two years later in 1838 that the painting appeared at the Royal Academy Exhibition, which was being held in its new home at the National Gallery, the R.A. having just moved from Somerset House that year. This beautiful painting is dated 1838 which leads us to believe that the original work started in 1836 was re-worked in late 1838 whilst the artist was in London. This large studio work derives from a number of oil sketches which Fearnley made in late 1835 whilst he was in the Grindelwald valley. The spectacular view we are looking at is of the upper Grindelwald glacier, which lies on the northern side of the Bernese Alps. In the middle ground we can just make out a lone shepherd silhouetted against the stunning white ice peaks of the glacier. In the foreground of the work we see that Fearnley has put a lot of effort into depicting the flora, amongst which are dotted the shepherd’s flock. Although my attached picture might not clearly show it, the artist’s signature “Fearnley” is on the rock in the right foreground, next to a fern ! Coincidence or a witty visual play on his name?