Mary Taylor Blood was born on May 13th, 1819. Her father was Reuben Blood, Jr. and her mother was Sally Taylor Blood and they lived in Sterling Massachusetts. Mary had two older brothers but was the eldest of four sisters. When she was still only a child, she was enrolled in Miss Thayer’s school, where she learned to paint with watercolours. Having shone as a potential artist she later moved to the Quaker’s Fryville Seminary in Bolton, Massachusetts. This school was established in 1823 by Thomas Fry, a local Quaker, as a co-educational preparatory school. It was here that she improved her skill as an artist and developed her early talent for sketching and painting.

Whilst still a teenager, the family moved to Fitzwilliam, New Hampshire and as fate would have it a young Universalist minister, Reverend Charles W. Mellen, arrived to act as pastor in the neighbouring towns. Reverend Mellen came from a family of farmers from nearby Phillipston and soon after, he and Mary met and the couple fell in love. In 1840 Mary and the Reverend Charles Mellen, married and went to live in Gloucester, Massachusetts. Mary and her husband relocated many times due to his pastoral work and in 1846 while living in the Massachusetts town of Foxborough, Mary gave birth to a daughter, Amanda. Sadly the baby only survived for forty-eight hours and the gravestone they erected at the site of the grave had the poignant inscription:

“…Our short-lived flower returned unto God…”

Even sadder was the fact that the couple never had any other children. Mary was fortunate that she had the support of her husband during these sad times and he was also very supportive with regards Mary’s artistic work.

Mary’s brother-in-law, William Grenville Roland Mellen, was also a Universalist minister and in the late 1840’s had his ministry in Cambridge Massachusetts and Mary and her husband made a number of visits to visit him in the city. Cambridge was a metropolitan suburb of Boston and at the time Boston was considered to be the New England’s centre of culture. In the city there was the Boston Athenaeum which is one of the oldest independent libraries in the United States. In the years 1872–1876, Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts exhibited in the Athenaeum’s gallery space while waiting for construction of its own building to be completed and at that time it boasted the largest art collection in New England. One can be sure that Mary Mellen, whilst visiting her brother-in-law and his family, found time to visit the building and discover the artistic treasures it held. Some of the works on display which Mary would have seen were by the American painter and printmaker, Fitz Henry Lane.

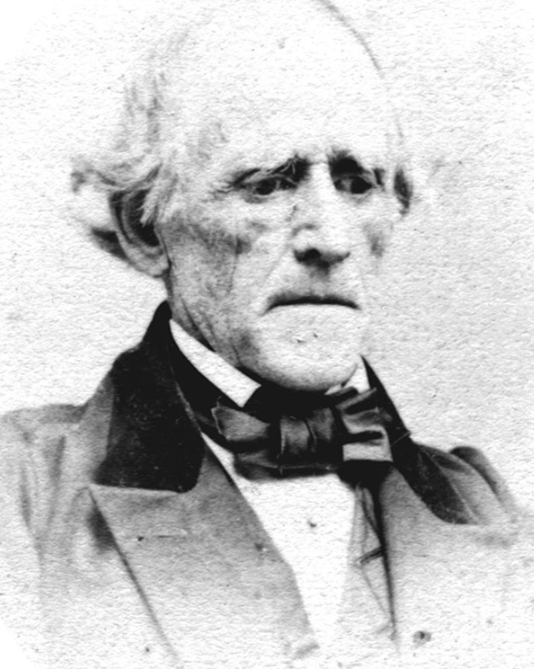

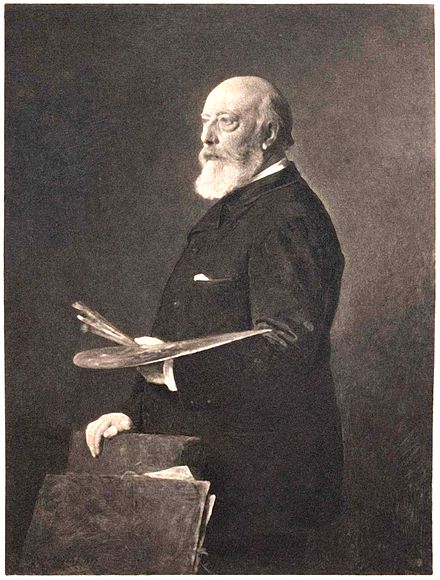

Fitz Henry Lane was born in the fishing port of Gloucester, Massachusetts on December 18th,1804. He was actually born Nathaniel Rogers Lane but in 1831, when he was twenty-seven, he legally changed his first and middle names, becoming known as Fitz Henry Lane. He suffered various illnesses as a young child. The most severe was paralysis due to infantile polio and after this illness he had to use crutches. Lane learned the basic art techniques while in his teens and in 1832 he started work with a firm of lithographers in Gloucester. Later in 1832, he moved to Boston for formal training and enrolled as an apprentice with William S. Pendleton, who owned one of the city’s most important lithographic firm. Lane stayed working for Pendleton until 1837, during which time he produced many illustrations for sheet music and scenic views.

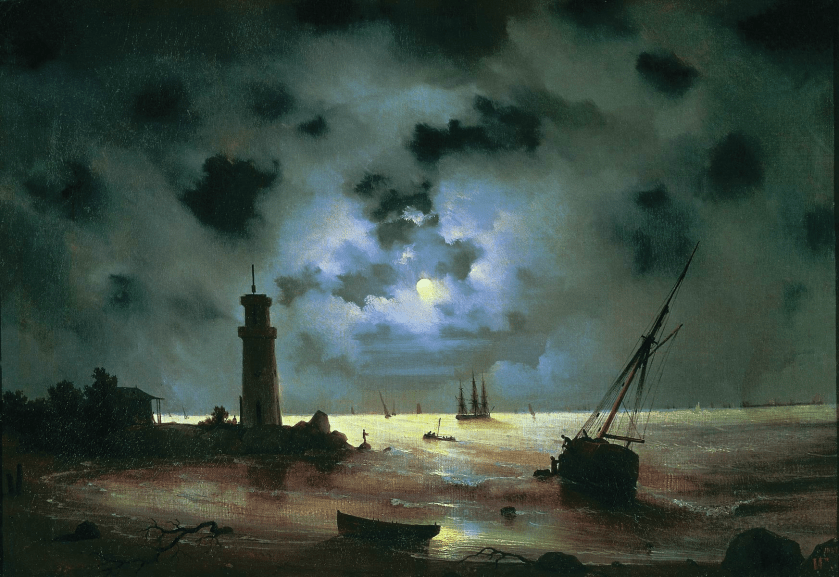

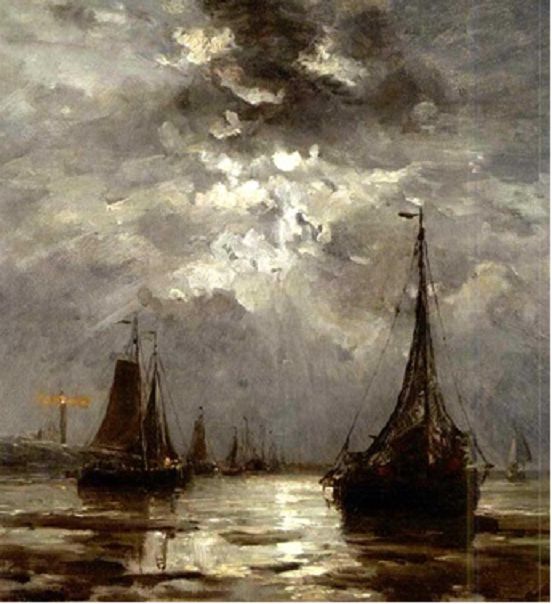

Whilst living in in Boston, Lane became aware of the artistic works of the English-born artist Robert Salmon, who was looked upon as the most accomplished marine painter in the area. Works of art by Salmon with their precisely detailed ships and sharply rendered effects of light and atmosphere had a pivotal influence on Lane’s early style. By 1840, Lane had produced his first oil paintings and soon he was listed in a Boston almanac as a “Marine Painter.” His works were first exhibited at the Boston Athenaeum in 1841 and, after 1845, his works were regularly shown there.

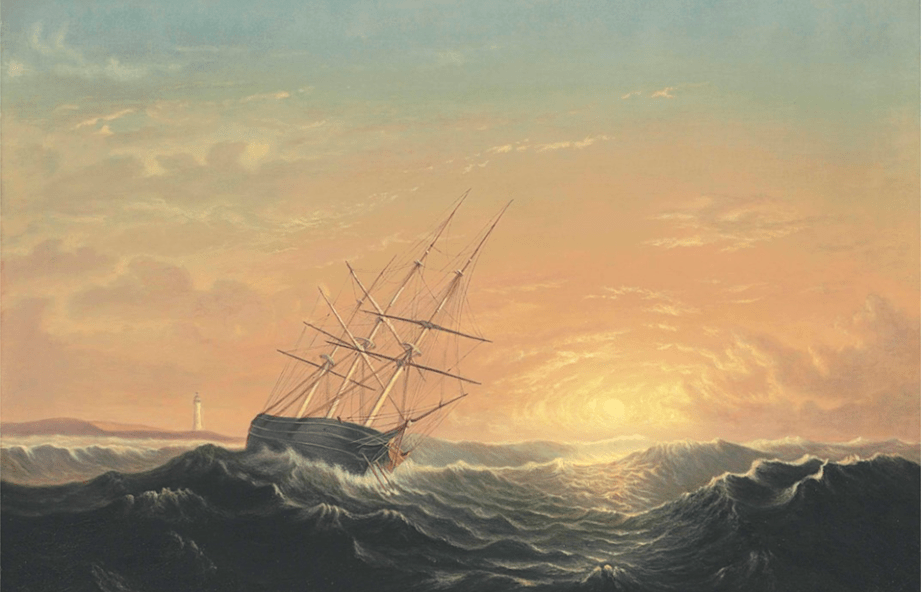

One of his very fine ship portrait is his 1853 painting entitled Clipper Ship Sweepstakes. The work is thought to be a pendant piece of his 1854 work entitled The “Golden State” Entering New York Harbor, The Golden State was another clipper ship owned by Chambers and Heiser who probably commissioned both works.

This large work, The Golden State entering New York Harbor, was some four feet wide, and is considered one of Lane’s masterpieces. The location in the depiction is not known, but it could well be the broad bay at the mouth of New York harbour. It is a blustery day with scudding clouds and a frothy chop in the very green water. The ship is flying a blue-and-white swallowtail pennant with a red tail—the house flag of Chambers and Heiser—on its foremast. An American flag flies off its stern.

However, although there is no evidence that Mary Blood Mellon was formally apprenticed to Fitz Henry Lane, his early years spent working in various lithography workshops would have impressed upon him the value of having an apprentice and the connection became an asset to both the master and the student. By the mid-1850s, it seems that Mary Mellen was working alongside Lane in his Gloucester studio, and the “coupling” was working well as it appears that Lane had given Mary free access to his drawings and on some occasions allowed her to make copies from his canvases. Her copies were so good and her stylistic faithfulness increased, such that, at a later time, even Lane himself appeared uncertain as to which was his when both were shown side by side.

A classic example of the this can be seen when you look at both their renditions of a scene entitled Owl’s Head, a coastal town in Knox County, Maine. Fitz Lane completed his painting (2) Owl’s Head, Penobscot, Maine in 1862. Lane painted Owl’s Head, (1), named for its distinctive profile, from the east, with the Camden Hills beyond. The land formations delicately mirrored in still water, the clear sky, and the pale, salmon colours of early morning emphasize the atmosphere rather than the topography of the site. On the back of the painting, an inscription in Lane’s handwriting establishes it as his own work: Owl’s Head–Penobscot Bay, by F.H. Lane, 1862.

The curators and conservators of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston compared paint application and the use of colour in the paintings by Mellen (1) and Lang (2). In general, they stated that Lane’s brushstrokes seem crisper, and he more precisely defines compositional elements such as the pine trees. They also concluded that Lane’s palette is also cooler than Mellen’s. Yet on careful examination, they agreed that these details can sometimes be too close to definitively separate the authorship and it could be entirely possible that, in studio tradition, Lane contributed to Mellen’s paintings, even if she signed them, and this complicates the issues of attribution even further.

Mary Mellen was said to have copied Lane’s style so that even he could not tell which was his own painting. In his 2006 book, Fitz H. Lane: An Artist’s Voyage through Nineteenth-Century America (2006), the author James A Craig wrote:

“…Mrs. Mellen is so faithful in the copies of her master that even an expert might take them for originals. Indeed, an anecdote is related of her, which will exemplify her power in this direction. She had just completed a copy of one of Mr. Lane’s pictures when he called at her residence to see it. The copy and the original were brought down from the studio together and the master, much to the amusement of those present, was unable to tell which was his own, and which was the pupil’s…”

This copying was not unusual in an artist-apprentice relationship. What confuses some art historians as to the attribution of a painting as it appears as though Mellen had a hand in completing parts of several Lane paintings, or may have even sketched certain landscape views that would have been difficult for Lane to access, given his lameness

There is only one known work signed by both Lane and Mellen, and this is their 1850’s work entitled Coast of Maine. Both Mellen and Lane signed the back of the canvas of the small tondo.

In August 1859 Mary Mellen and Fitz Henry Lane travelled together to to visit the Blood family residence in Sterling, Massachusetts, where they both created paintings of the Blood homestead with the two paintings depicting a different season.

It is thought that by 1861 the Mary Mellen and her husband were living in Dorchester, Massachusetts, which was only a short distance from Gloucester. Three years later, the couple moved again, this time to Taunton, Massachusetts, which was about forty miles south of Boston.

Mary Mellen suffered duel losses in the mid 1860’s. Fitz Henry Lane had been unwell throughout 1864 and 1865 and this culminated in a bad fall in August 1865, followed by a heart attack. He died in his home on Duncan’s Point on August 14th, 1865 and is buried in Oak Grove Cemetery. One of Boston’s newspapers described his death as “a national loss,” however Lane’s reputation during his lifetime was mainly local and after his death he and his works were largely forgotten outside Gloucester. A year later Mary’s husband, Reverend Charles W. Mellen, died suddenly and unexpectedly at the age of forty-eight. Following Lane’s death in 1865 and Charles Mellen’s death in 1866, Mary Mellen, now widowed and childless, moved to Connecticut to live with her widowed sister-in-law, Sophronia Haskell.

Mary Mellen carried on painting until her death on February 11th,1886, when she died of typhoid at the age of sixty-six in Sterling, Massachusetts. Her passing was noted in several newspapers with obituaries acclaiming her as “a woman of great acquirements and an artist of prominence. Her specialty was marine work and her pictures were very popular.” Her will, which she had made in 1882 stipulated to which niece and nephew each of her original paintings by Fitz Lane should go. She also insisted that Lane’s nephew Fitz Henry Winter should receive a painting by Fitz Lane, as well as a portrait of him that was in her collection. In recent years, art historians recognize Mary Blood Mellen as one of the most accomplished artists to work on Cape Ann in the years immediately preceding the Civil War.

The sheer size of this work, 304 x 505cms (119 x 199 in) is breathtaking.

The sheer size of this work, 304 x 505cms (119 x 199 in) is breathtaking.