There has been a much longer period since my last blog than I would have liked or I had intended. I could simply explain that the reason for the delay being down to how busy I am with my Bed and Breakfast business, which is true, but there is another reason. My blogs, as you know, take the form of an artist’s biography or the biography of the sitter and the painting itself. The problem arises when I get sucked into the life of the artist or sitter. The more I read of their life story, the more I delve further into their personal life and time soon passes. Then of course I have to decide what to leave out to make the blog more manageable. The problem with reading from so many sources is that they do not always agree on dates so I have had to make educated guesses in some cases as which of the sources is correct. Sometimes the life story of the artist is so fascinating and so all-consuming, as is the case of today’s artist, I just don’t want to edit out any of the details and so have to run with the artist over a number of blogs. My featured artist today is the Mexican painter Frida Kahlo. Her life was controversial, traumatic and often full of sadness and as I recount her fascinating life story in the next few blogs, I will look at a couple of her paintings. Today I want to focus on her arrival into this world, her family and her ancestors.

Frida was born Magdalena Carmen Frieda Kahlo y Calderón on July 6, 1907 at the family home, La Casa Azul (The Blue House) that was built in 1904 by her father in Coyocoán, a small town on the outskirts of Mexico City. She was later to change the German spelling of her Christian name from Frieda to Frida.

Her paternal grandparents, Jakob Heinrich Kahlo, who owned a jewellery shop, and Henriette Kahlo (née Kaufmann) were European Jews who originally came from Arad, which was formerly part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire but which is now part of Romania. Much has been written about this assertion by Frida Kahlo that she has Jewish ancestry. However, the Jewish family connection and ancestry has been contested a number of times. In a 2006 newspaper an article by Meir Ronnen in the Jerusalem Post cast doubt on the authenticity of the Jewish claim. In a book published in 2005 by Gaby Franger and Rainer Huhle, about the photography of Frida’s father entitled Fridas Vater: Der Fotograf Guillermo Kahlo they dispute Frida’s assertion of her Jewish ancestry, agreeing that her father was born in Germany but that he came from a long line of German Lutherans and they reasoned that Frida’s story of Jewish heritage was so that she could disassociate herself from the German Nazis during World War II.

In 1860 the family moved to Germany. Frida’s father, Wilhelm Kahlo, was born in Baden- Baden in October 1871 and was the eldest of four children. After early schooling, he attended the University of Nuremburg, however the onset of epileptic seizures cut short his academic studies. In 1890 Frida’s paternal grandmother Henriette died and her paternal grandfather married Ludowika Karolina Rahm. Frida’s father Wilhelm did not get on well with his stepmother and with financial help from his father he decided to leave the family home and leave Germany altogether. The following year, 1891, Frida’s father who was just nineteen year old, set sail from Hamburg on the freighter Borussia bound for Vera Cruz, Mexico. His complete change of lifestyle included changing his forename name from the Germanic Wilhelm to the Spanish Guillermo although throughout his life he never lost his Germanic ancestry as he always spoke with a heavy German accent and Frida referred to him in mock formality as “Herr Kahlo”. He soon found work in the up-market Diener Brothers jewellery store in the city, probably through his German/Jewish jeweller connections.

Guillermo married his first wife Maria Cardena in 1895 and the couple had three daughters but sadly the middle girl survived only a few days after her birth. Maria Luisa, born in 1894, was the eldest and Margarita the youngest. The marriage ended tragically in 1898 when his wife died during the birth of their third child, Margarita. The night his wife died he sought help and comfort from his co-worker at the jewellery store, Matilde Calderón and her mother, Isabel, both of whom came to his house to offer their support. Matilde Calderón y Gonzalez was a woman of Spanish and Mexican-Indian descent. Her mother was a Spanish Catholic and her father was a native Mexican Indian. Guillermo now faced having to bring up a four year old girl and a baby alone and he did not keep the best of health as throughout his life as he continued to suffer from bouts of epilepsy. Whether it was because he knew he would be unable to cope alone bringing up his two young daughters, whether he wanted to avoid loneliness or whether, according to Raquel Tibol in her 1983 biography, Frida Kahlo: an Open Life, we should believe Frida when she says her father and mother simply fell in love. Whatever his reason was, he soon proposed to Frida’s mother, Matilde Calderón, and they were married later that year. Matilde was twenty-two years of age and Guillermo twenty-seven years of age when they got married. The couple went on to have four daughters of which Frida was the third. She had two older sisters, Matilde born in 1899 and Adriana born in 1902, and one younger sister, Cristina, who was born in 1908.

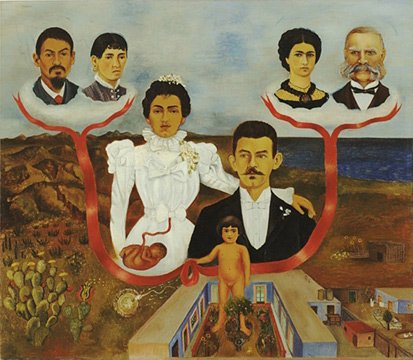

The reason I gave you that detailed family tree was as an accompaniment to the very unusual painting I am featuring today, which Frida Kahlo completed in 1936 entitled My Grandparents, My Parents and I (Family Tree).

Frida described the work:

“….Me in the middle of this house, when I was about two years old. The whole house is in perspective as I remember it. On top of the house in the clouds are my father and mother when they were married (portraits taken from photographs). The ribbon about me and my mother’s waist becomes an umbilical cord and I become a foetus. On the right, the paternal grandparents, on the left the maternal grandparents. A ribbon circles all the group — symbolic of the family relation. The German grandparents are symbolized by the sea, the Mexican by the earth…”