Yesterday I looked at a painting by the Belgian artist Antoine Wiertz and bemoaned the fact that although I could discover facts about the artist himself, I could find little information about the featured work of art. I have no such problem with today’s featured painting, A Bar of the Folies Bergère by Édouard Manet. Much has been written about this enigmatic painting. This will be the fourth occasion that I have featured one of Manet’s works and so I will not repeat his life story which you can find in my previous blogs (October 11th and 12th and November 9th). Today in My Daily Art Display I want to simply concentrate on the painting itself.

As I have mentioned on a number of occasions previously, I believe that when you have a limited time in a town and you want to visit an art gallery it is sometimes better to go to a smaller one rather than rushing around a large establishment trying to see everything and failing miserably. Today’s painting hangs in the Courtauld Gallery in London which in comparison to the National Gallery or the Tate Galleries is somewhat smaller but what its collection lacks in quantity really comes into its own when it comes to quality. I first visited the Courtauld Gallery when I went to see Cezanne’s Card Players exhibition after which I decided to spend a few hours taking in the gallery’s permanent collection and it was then that I came across this fascinating and famous work by Manet.

The Folies Bergère, as most people know, is a famous Parisian night-club situated in the 9th Arrondissement of Paris, not far from the heart of the post-Haussmann cultural centre of Paris, south of Montmartre, and a little east of the boulevard des Italiens (known simply as The Boulevard). The venue is located at 32 rue Richer, the same place that once housed a department store called ‘In the Pillars of Hercules’ . After almost four years, the departmental store went out of business and so in 1867 it was decided that the store should be replaced a public auditorium. The construction lasted for almost two years and it was the first music-hall to be opened in Paris. It was based upon an imitation of the Alhambra in London, a music hall known and much-loved for broad comedy, opera, ballet and circus. It opened in May 1869, a year before the start of the Franco-Prussian War, and is still in business today. It was originally called the Folies Trévise because it was on the corner of the rue Richer and the rue Trévise but the name was changed in September 1872 because the Duc de Trévise would not allow his name to be brought into such potential notoriety. As the rue Bergère, a road named after a master dyer, was just a couple of blocks away, the decision was made to rename the establishment as the Folies Bergère. A Folies-Bergère show typically included ballet, acrobatics, pantomime, operetta, animal acts, and many included spectacular special effects. However, the Folies-Bergère was perhaps more well-known for its sensual allures. It became chic to be seen at the Folies Bergere, so aristocrats and royal families alike came from all over the European continent to claim their coveted seats at the Folies. Manet’s picture features his friends, both artists and models and was the kind of trendy place in which he spent his evenings. The painting we see before us was the last great work of art painted by Édouard Manet and was completed in 1882. At the time Manet was suffering badly from a debilitating disease, brought on by untreated syphilis, which he was to die from the following year.

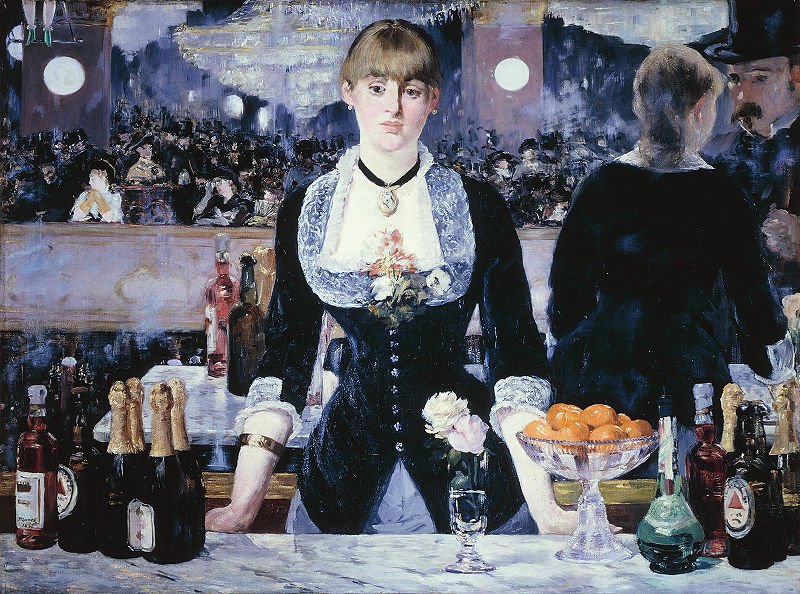

So what are we looking at? The woman in the painting is Suzon a waitress at the establishment, who posed for the picture in Manet’s studio. When I first glanced at the painting I thought I was simply looking at a woman standing behind a marble-topped bar and behind her were a large throng of people who were enjoying a meal whilst watching the entertainment but in fact what we are looking at is the woman standing between us and a large mirrored wall, the bottom of its gold frame can be seen running the full width of the painting, and it reflects what is actually going on behind us as we stand at the bar. The young woman, who rests her hands on the counter, wears a greyish blue skirt and a dark velvet jacket with a low-cut lacy collar and has a corsage of pink flowers at her breast. She has blonde hair which is tied back and wears two small drop-earrings and a gold bangle on the wrist of her right hand. The woman before us is not looked upon as a just a simple bar tender but more than likely falls into the category of a demimondaine. A demimondaine was a term used to describe a professional mistress who sold her company, affections and body in exchange for being maintained by a patron in a long term relationship. Later the word became a euphemism for a courtesan or prostitute. Some art historians have interpreted the main aspect of the painting, the woman, as not only the seller of the bottled products we see on the counter before her but possibly the seller of her own body.

Now cast your eyes to the right of the woman and we see the reflection of the woman, or do we?. Should we simply believe that we are looking at a mirrored reflection of her? If Manet has simply drawn her mirrored reflelection, how could it be, as if the mirror is parallel with the plane of the painting then the reflection of the woman should be directly behind her and thus out of our line of sight. In the painting the waitress stands before us, upright and is looking directly out at us and yet the reflection of her as depicted in the painting has her bent over slightly turned sideways as she talks to a gentleman with a moustache and wearing a top hat. Something is not right. Many believe that in actuality Manet had not meant it to be a true mirrored reflection of the back of the woman but the image of the woman at another time in her life. Maybe Manet wanted it to be a depiction of what she is thinking as she looks into our eyes. Maybe she is dreaming of meeting her gentleman lover or remembering the intimate time when they last met. In Jeffrey Meyers book Impressionist Quartet: The Intimate Genius of Manet and Morisot, Degas and Cassatt, he describes the intentional play on perspective and the apparent violation of the operations of mirrors:

“Behind her, and extending for the entire length of the four-and-a-quarter-foot painting, is the gold frame of an enormous mirror. The French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty has called a mirror ‘the instrument of a universal magic that changes things into spectacles, spectacles into things, me into others, and others into me.’ We, the viewers, stand opposite the barmaid on the other side of the counter and, looking at the reflection in the mirror, see exactly what she sees. Her own reflection, however, is not directly behind her, according to the strict rules of perspective, but at a right angle to where she’s standing. It seems to reveal her long hair, cheek, collar and back as she serves and chats to male customer. A critic has noted that Manet’s ‘preliminary study shows her placed off to the right, whereas in the finished canvas she is very much the centre of attention.’ Though Manet shifted her from the right to the center, he kept her reflection on the right. Seen in the mirror, she seems engaged with a customer; in full face, she’s self-protectively withdrawn and remote.”

In an early preparatory sketch for this painting Manet placed the woman to the right of the picture and then her reflection in the mirror seems more realistic.

The woman intrigues me. I look at her and try and interpret her expression and by doing so, I may be able to build up a picture of her existence. How would you describe her expression? Is it one of unhappiness, one of disappointment, maybe one of nervousness? Her mind seems somewhere other than with us. Her cheeks are flushed. Is it simply due to the heat of the theatre or maybe it is a sign of extreme weariness. In some ways she has a look of innocence but her reflected image talking to a customer or client belays that thought. So in a way, maybe we are being asked to decide who the real woman is; the one who innocently looks out at us or the one who could well be negotiating the sale of herself?

Look at the bar which separates us from the woman. On it we see a glass bowl containing oranges or mandarins, a small glass with two flowers in which we see a partial reflection of the woman’s corsage and an array of bottles of unopened champagne. Critics have also pointed out that the mirror does not correctly reflect the bottles on the counter in type or quantity. However more interestingly, note the bottles with the red triangle on the label.

This was not a French product but Bass, a well known brand of English beer which was established in Burton on Trent by William Bass in 1777 and still can be bought today. The inclusion of these bottles in the painting, which in present day terminology would be called product-placement, signifies the varied clientele. Members of the Jockey Club and English bookmakers used to congregate every evening at the Folie-Bergère bars and Bass beer was brought in especially for them. Another interesting detail about the bottles on the counter is that the artist himself has signed his name “Manet 1852”on the label of the bottle containing the red liquid, on the far left.

The reflected background shows the interior of the theatre with its gilded balcony front and its large chandeliers hanging down from the high ceiling. It is a glittering scene depicting a sensuous world of pleasure. Round electric lights can be seen on the pillars which must have been in themselves a novelty as this type of lighting had only just come into being. Look to the upper left corner of the painting and you can just make out a swing and a pair of small green-booted feet which belong to the trapeze artist who is poised aloft on a swing, performing for the theatregoers.

When this painting was lent out to the Getty Center in 2007 a mirror was installed to help dramatize the questions of vision and reflection raised by Manet’s painting. The painting raises so many questions and as Manet is not with us to explain his work, one can only guess at the answers. So I will leave you to ponder these points:

How would you describe the barmaid’s vacant expression, one of remorse, one close to tears ?

What had Manet in mind when he painted the off-set reflection of Suzon and why did he position her at the centre of the painting whereas in an early preparatory sketch she is to the right of the painting and the mirrored reflection of her seems more real?

The reflection shows a man talking to Suzon but why is he not shown on the side of the bar where we are standing?

We are standing on a balcony walkway in front of the bar and yet it is not shown in the mirrored reflection, why?

The marble bar top on which Suzon rests her hands stretches the full width of the painting and yet the reflected image of the of the bar top does not, why?

This is a truly intriguing painting and the next time you are in London you should make time to visit the Courtauld Gallery and stand in front of Suzon and see what you make of the painting.