William Merowitz in his studio.

John Weichsel was the founder of the People’s Art Guild in 1915. It was to be an alternative to the system of traditional fine art galleries. The Guild would set up exhibitions in various unconventional spaces and by doing so, the Guild brought avant-garde art into the immigrant settlement houses and tenements of the Lower East Side with the goal of exposing a new set of people to modern art and at the same time, providing artists with direct contact to new markets. One of the helpers at the Guild was William Meyerowitz.

Theresa and William’s Wedding Photograph (1919)

Meyerowitz called on Theresa at her studio and asked if she could offer some of her paintings for a benefit show with the Guild. From this initial meeting a friendship developed which blossomed into romance and finally on February 7th 1919 the couple married in Philadelphia.

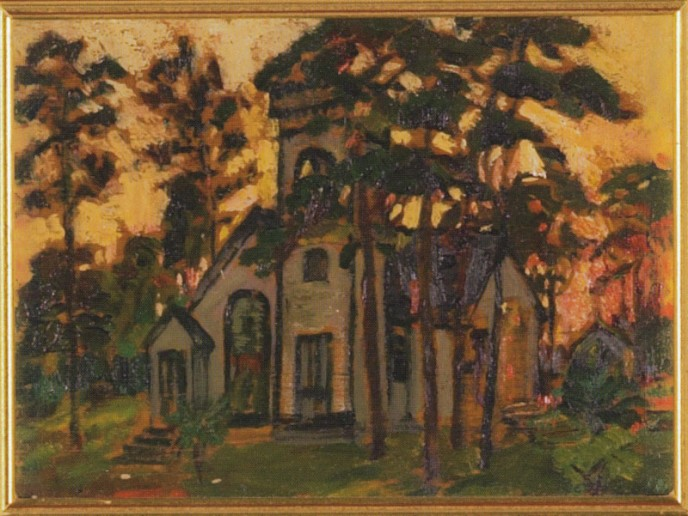

The Studio (54th West 74th Street) by William Meyerowitz (1935)

William Meyerowtiz was born in Ekaterinoslav, now Dnipro in Eastern Ukraine, on July 15, 1887. He and his father had immigrated to New York City in 1908, and they settled in the Lower East Side. William studied etching at the National Academy of Design and was also a talented singer and while he was a student he sang in the chorus of the Metropolitan Opera. Later, he rented a studio in the same building as the 291 gallery run by Alfred Stieglitz.

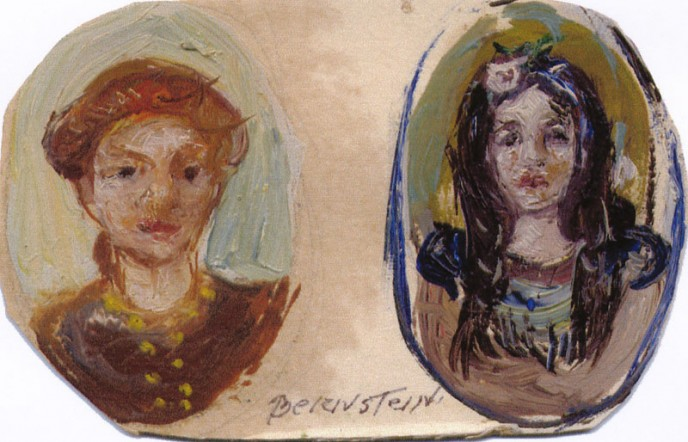

Portrait of the Artist by Theresa Bernstein (1920)

Their marriage took an early blow when their baby daughter died of pneumonia. and from that tragedy, they remained childless. Despite this tragic occurrence the couple lived a happy and contented life. In her 1986 biography of her husband, William Meyerowitz, The Artist Speaks. Theresa Bernstein Meyerowitz wrote:

“…In the Autumn evenings, we used to take a little table from the studio and place it in front of the fireplace. William would split some logs and light the fire. … We would have cozy conversations about our work, our friends, ourselves and they were precious evenings we spent together. We never tired of each other’s company. . . . From the day we met, our life was one absorbing conversation...”

The Immigrants by Theresa Bernstein (1923)

In 1891, Theresa Bernstein had been an immigrant entering America with her mother and father when she was just one-year-old. Thirty-two years later she completed a painting entitled The Immigrants, depicting the deck of the Cunard liner, Aquitania and the plight of immigrants heading for the “promised land”. The centre point of this depiction is a young mother and her baby and maybe Theresa wanted, through this painting, to recall what it would have been like for her mother making that sea passage across the Atlantic. The young woman is surrounded by her fellow immigrants. She seems to be lost in her thoughts. What are her thoughts? Behind her right shoulder is a young man hovering nearby. Could she be thinking of a new relationship, a new romance? Behind her left shoulder is a group of children with their mother. Maybe the young woman daydreaming about a happy family life with numerous children. This is a depiction which directs our thoughts on the vulnerability, change and challenge which affect this young woman but at the same time offers a glimmer of hope with regards her possible new beginning.

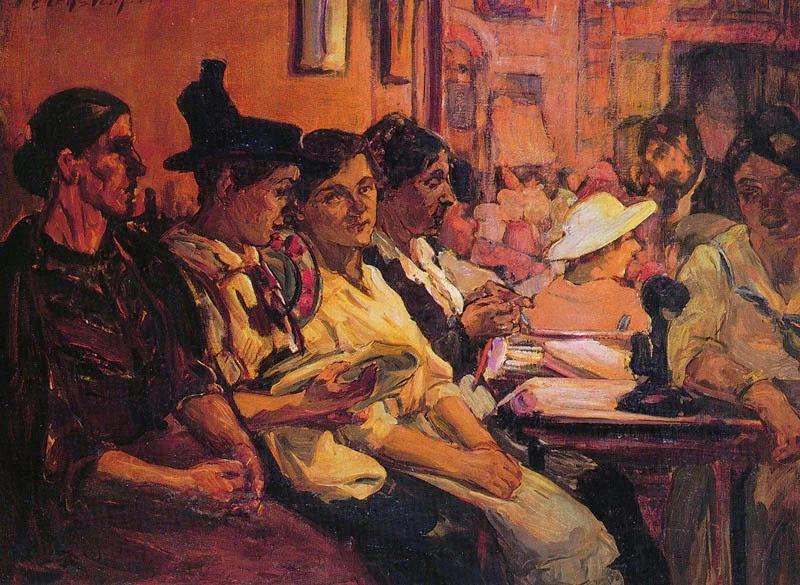

The Milliners by Theresa Bernstein (1921)

Bernstein’s 1921 painting entitled The Milliners is typical of many of her figurative works depicting a large group of people. Look back at some of her multi-figured paintings: the job-seekers in a crowded waiting room (Waiting Room – Employment Office), people crowded into a train on the elevated railway (In the Elevated), and many others depicting beach scenes at Coney Island or audiences at the music hall or theatre. Theresa was Jewish and although this 1918 painting, The Milliners, could not be termed Jewish, it was personal to Theresa as her sister-in-law worked in the millinery industry, a typical “vocation” that was both immigrant and Jewish.

View through window (The Milliners)

In the painting we see a group of female workers, engaged in the fastidious and creative labour of creating hats. It depicts six women gathered around a table which is brimming with accessories. The depiction is a close-up of the women and this view emphasizes the cramped nature of the space that the women are working in but it also offers us a close look at their individual features. The setting is probably a room in a city tenement apartment. If you look carefully at the upper left, you can just make out a window, windowsill and through this space we can just make out the metal fire escape which was common in this type of building.

Mother and Mother-in-law

This is also a depiction of Theresa’s beloved family. Theresa’s mother is the woman we see depicted at the upper left of the group, with greying hair, talking to Theresa’s mother-in-law, whose hands hide the delicate threads she is working with, head bowed as if in prayer. On either side of the mothers are two of Theresa Bernstein’s sisters-in-law, Bessie and Sophie, who was actually a milliner herself. One of them, dressed in black, has placed a newly made black hat on her head and is admiringly viewing the result in a hand-held mirror. Her sister, dressed in bright yellow, watches as her sibling vainly gazes lovingly at her reflection. She holds a black hat which has two large flame-like yellow feathers attached to it. In the lower right of the group, diametrically opposite her mother, is Minna, Theresa’s third sister-in-law, dressed in a white dress and they are testament to two generations of milliners. The final member of this working group of women sitting on the far right, dressed in green, is Katie. She is the only one to be looking out us. Maybe she is silently inviting us into this intimate circle. Katie was the family housekeeper and Theresa’s much-loved confidante.

Katie by Theresa Bernstein (1917)

Katie, the Bernstein’s housekeeper was the subject of Theresa’s portrait in 1917. Although Theresa thought of her as a friend and part of the family. For Katie, her role in the Bernstein household was somewhere between an employee and a sister to Theresa. Bernstein did not choose sitters for their glamour or their social status, her choice of subjects was based upon people she liked. In this portrait which uses earth tones we see Katie wearing a heavy shabby coat. She is pinching the lapels tightly together. On her head is a hat, with the haloed brim positioned at a jaunty angle allowing the feathers, attached to it, to cascade downwards.

Woman with a Parrot by Theresa Bernstein (c.1917)

Elsa Baroness von Freytag-Loringhoven the German-born avant-garde visual artist and poet, who was active in Greenwich Village, New York, from 1913 to 1923, where her radical self-displays came to embody a living Dada. She was considered one of the most controversial and radical women artists of the era. Theresa Bernstein painted several striking portraits of this Dada artist, poet, model, and muse, whom she befriended in New York’s Greenwich Village. Was it the sitter’s uncompromising attitude to life which attracted Bernstein for she too was equally radical in her own time, as she established her own path as a Jewish immigrant and a female artist in the male-dominated art market. In this painting entitled Woman with a Parrot which she completed around 1917, we see the baroness gracefully poised against a plain background; her back is partially exposed, and she holds a red parrot.

The Cribbage Players by Theresa Bernstein (1927)

The New York Society of Women Artists (NYSWA) was founded in 1925 and devoted itself to avant-garde women artists. Theresa Bernstein was one of the earliest members and and took part in this and other women artists’ groups throughout her career. Theresa was acutely sensitive to the discrimination against her within the profession because she was a woman and for that reason, she would often use only her first initial when exhibiting, especially at the National Academy of Design. She was both disillusioned and disappointed with never having been nominated to the Academy. She would often amusingly recount an anecdote about the male artistic preserve, the Salmagundi Club of New York City. (It only began to admit women in the 1970s.) Her story goes that a delegation from the club visited her studio at one point in search of a Mr. Bernstein. At first Theresa believed that they were looking for her father. After some amusing banter, it soon became apparent that they wished to offer “Mr. Bernstein” a membership in the club and they stalked off in a mood when they found out that the painter of the canvases, they so admired, was in fact Theresa Bernstein.

Metropolitan Opera by Theresa Bernstein (1924)

Metropolitan Opera by Theresa Bernstein

Toscanini at Carnegie Hall (1930)

Two subjects that fascinated Theresa Bernstein and were often depicted in her works of art were her love of music which she had got from her husband and the depiction of crowds and both these elements can be seen in her depiction of musical events at the Metropolitan Opera House and Carnegie Hall,

The Music Lover by Theresa Bernstein (1913)

Theresa Bernstein died at Mount Sinai Hospital in Manhattan on February 12th 2002, sixteen days before her 112th birthday, although it is thought she may have been older, but she had never been forthcoming regarding her birthdate! Her husband William Meyerowitz had dies in 1981. She will always be remembered as one of the first to paint in the Realist style.

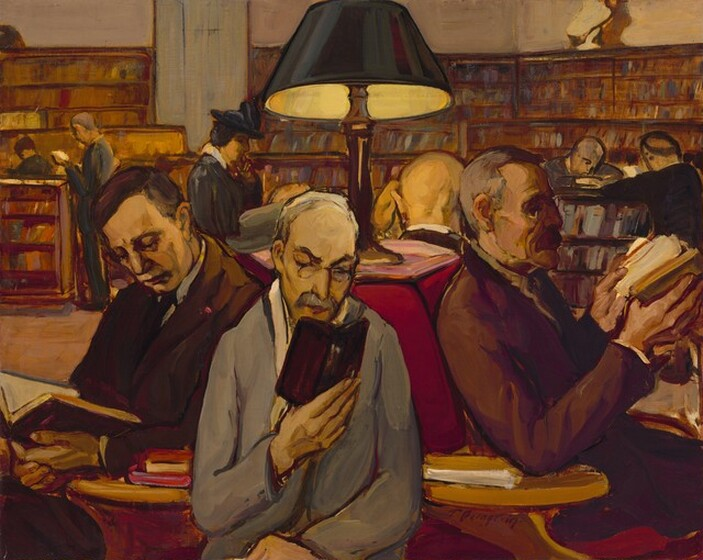

Music Lovers by Theresa Bernstein (1934)

I will leave the last words on this wonderful artist to Patricia M Burnham, lecturer in American studies and art history at the University of Texas, who wrote an article about Theresa Bernstein in the Woman’s Art Journal, Vol. 9, No. 2 (Autumn, 1988 – Winter, 1989). She wrote:

“…Her work has not gone unrecognized. Each decade of her 80-year career has been marked by gallery representation and one-woman shows. Her early work especially generated considerable excitement among reviewers and critics. But she has never gained the national reputation one might have expected nor are her works to be found in a large number of major art museums. Happily, Theresa Bernstein is now being rediscovered. Along with many other women artists, she has been a beneficiary of the women’s movement and feminist art scholarship.20 Art historians taking another look at early-20th-century American art are beginning to recognize her achievements. Yet to come is a full evaluation of her work that will reveal the weaknesses among the strengths, the particulars among the universals, the womanly among the human and ultimately provide a meaningful synthesis worthy of its subject…”