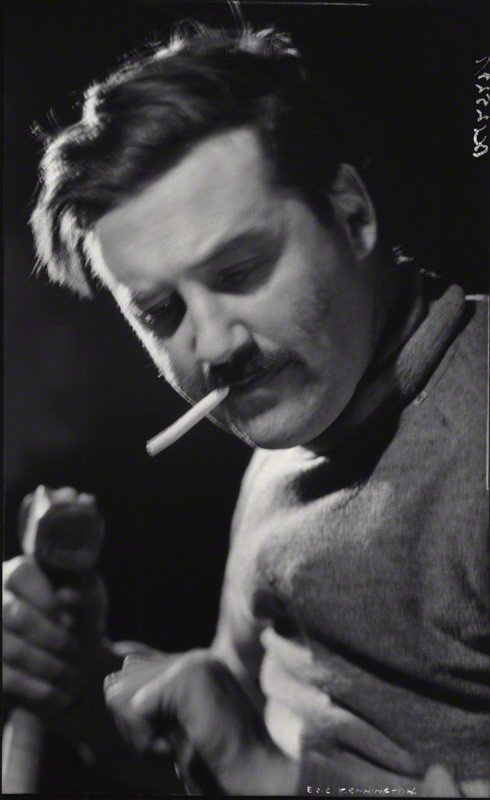

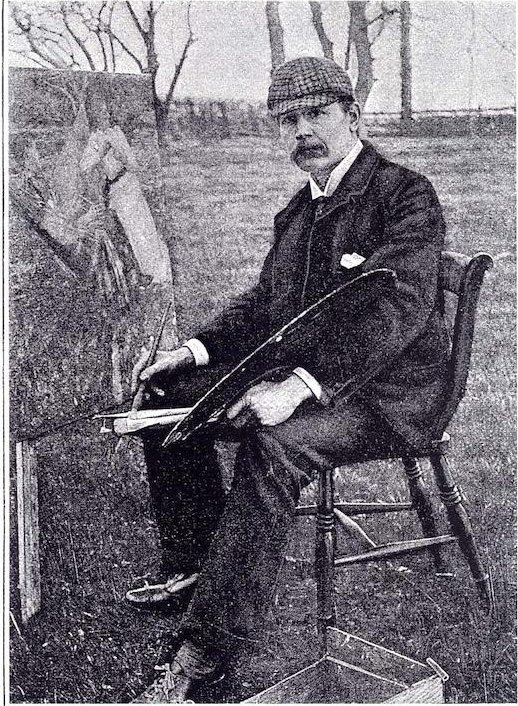

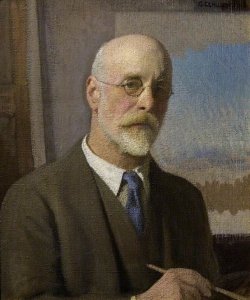

At the end of Part 1 of this blog about Eric Henri Kennington we had reached a point in his life when he had travelled to Arabia to prepare sketches which would later be used in his friend, T. E. Lawrence’s 1922 book entitled Seven Pillars of Wisdom.

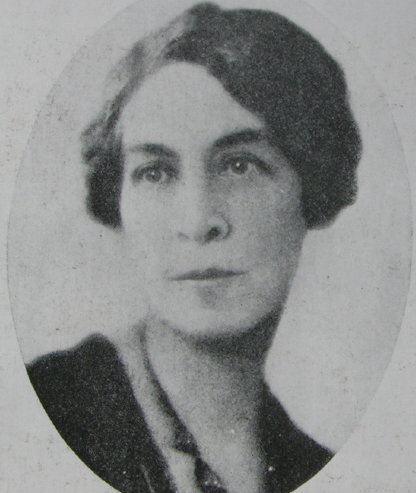

In 1922, Eric Kennington first met Edith Cecil when he received a commission to paint a portrait of her husband, William Charles Frederick Hanbury-Tracy, 5th Baron Sudeley, whom she married in August 1905. They had no children. Kennington and Edith fell in love and in 1922 she and her husband divorced and in September 1922 she married Eric Kennington. The couple went on to have a son, Christopher, in March 1925 and a daughter, Catherine in February 1927. It is said that both Eric and Edith remained on friendly terms with Edith’s ex-husband.

Eric Henri Kennington, as well as having been a war artist during the Great War, was also a revered portrait painter. During his time in Arabia sketching and working on paintings for T E Lawrence’s autobiographical book, Seven Pillars of Wisdom, he met Field Marshal Allenby. Allenby, at that time, was the High Commissioner for Egypt and was based in Cairo.

In March 1921 Kennington met Allenby at the Semiramis Hotel in Cairo and produced a pastel portrait of Allenby. It is remarkable to think that this pastel work was completed by Kennington in less than an hour.

Kennington and T.E.Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia) had an enduring friendship up until the day Lawrence was killed in a motorcycle accident in May 1935. After his friend’s death, Kennington spent years completing a full-length reclining stone effigy of his friend dressed as an Arab sheikh. This beautiful tomb effigy which was completed in 1939, and can now be found in the church of St Martin’s in Wareham in Dorset

Kennington also completed a bronze sculpture of the head of T.E.Lawrence in 1926 and the intrepid British archaeologist, military officer, and diplomat was delighted with the work. He said:

“…Magnificent; there is no other word for it. It represents not me but my top moments, those few seconds when I succeed in thinking myself right out of things…”

At the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 the War Artists Advisory Committee was formed as part of the Ministry of Information. The chairman of the new committee was Sir Kenneth Clark. Clark who had been a fine art curator at Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum, had, in 1933 at age 30, become the director of the National Gallery and as such was, and still is, the youngest person ever to hold the post. One of the artists he chose was Eric Kennington, as by this time, he had built up a reputation as a leading portrait artist. Kennington became a war artist for the second time in December 1939. His contract with the War Artists Advisory Committee was to produce pastel or charcoal portraits and for each one he would be paid 25 guineas. Kennington agreed but said he would need a minimum of three hours per sitter.

One of his first sitters was the Chief of the Imperial Staff, General Sir Edmund Ironside. He completed the portrait in January 1940

In 1940 Kennington was sent to Plymouth to sketch portraits some of the seaman who had served in the great 1939 sea battle of the River Plate. One such portrait, which he completed in the April of that year, was of Andrew Martin, a senior stoker aboard HMS Exeter during the River Plate battle. Kennington wrote a small piece to accompany the portrait. He wrote:

“…Man of Action: instantaneous: 100 per cent reliable: expert technician. Much humour under thorough camouflage. Very gentle, sensitive, and great physical strength…”

The painting found favour with the art critic, Herbert Granville-Fell who wrote:

“…Kennington’s harsh iron technique has a force admirably suited to conveying unflinching and dauntless resolution in the faces of his seamen and soldiers. I know of no other artist who can so convincingly depict the salt of the earth, and evoke palpably, in a portrait, the very essence and savour of courage…”

Kennington, as was the case during the First World War, soon clashing with his “employer” the War Artists Advisory Committee principally because of his personal dislike of Colin Coote, a journalist, who was the War Office representative on the committee. In May 1940 the Home Guard, the Local Defence Volunteers was formed and Kennington decided to leave his role as a war artist for the War Artists Advisory Committee and join the Home Guard.

In July 1940, shortly after Kennington left the War Artists Advisory Committee the Committee held an exhibition of official war art at the National Gallery. The art critics and public were both pleased with what they saw and in particular the works of Eric Kennington which were said to have been the most popular. In particular his works depicting the generals and the sailors received the most praise.

Kennington rose in its ranks and in July 1940 he was put in charge of a section of six countrymen in the south Oxfordshire countryside, defending an observation post he had set up to the north of his home in Ipsden. We are so use to thinking of the Home Guard as the people we see on the very popular TV comedy series, Dad’s Army or maybe we have a romantic view of the brave men who protected our homes. Apparently Kennington did not view the Home Guard or his fellow Home Guardsmen in such an idealised and romantic manner. Kennington was very vociferous in his criticism of the equipment they were given and was also critical with regards the senior officers, of whom he said were tied up in bureaucracy. He wrote to his older brother William:

“…The men, if not suitably motivated, did not report for duty in the evenings, but sloped off after roll call to go poaching, fishing, or playing cards in the pub…”

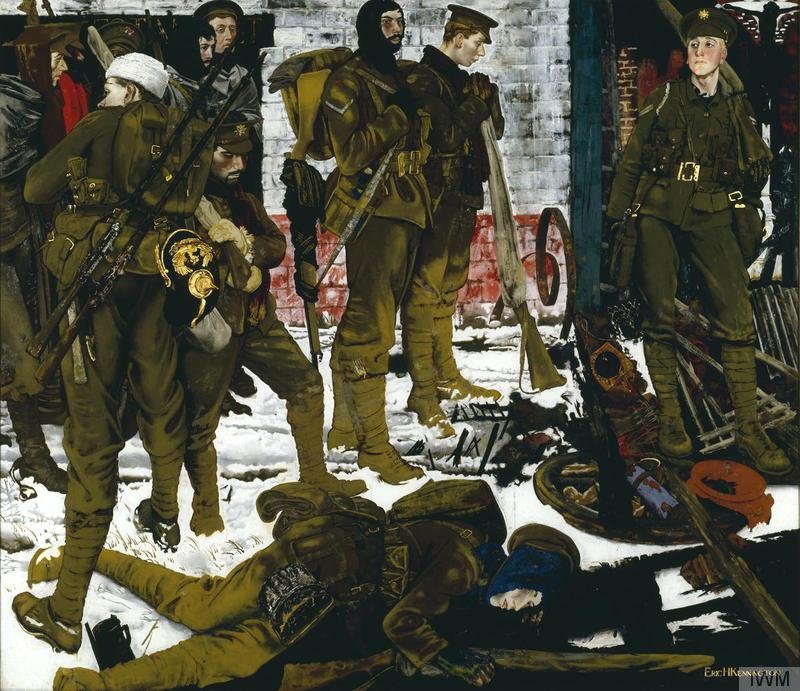

For all his criticism of some of his fellow volunteers he completed some wonderful portraits of them, such as Sergeant Bluett of the Cornwall Home Guard which he completed in 1943.

….and Corporal Robertson of the City of Edinburgh Home Guard which he also completed in 1943. Both these paintings are housed in the Imperial War Museum.

The War Artists Advisory Committee in August 1940 not wanting to have lost such a great artist approached Kennington and asked him to return to the fold as a war artist. The War committee was delighted that Kennington agreed to return. The secretary of the Committee, Edmund Montgomery O’Rourke Dickey, wrote to Kenneth Clark about how Kennington’s work instilled hope in those who saw his portraits. He wrote:

“…The best of this artist’s [Kennington] portraits of sailors in the exhibition at the National Gallery have, in the eyes of the public, a nobility not shared by any other work that’s on display at the National Gallery. These portraits typify the fighting man who’s going to win the war for us…”

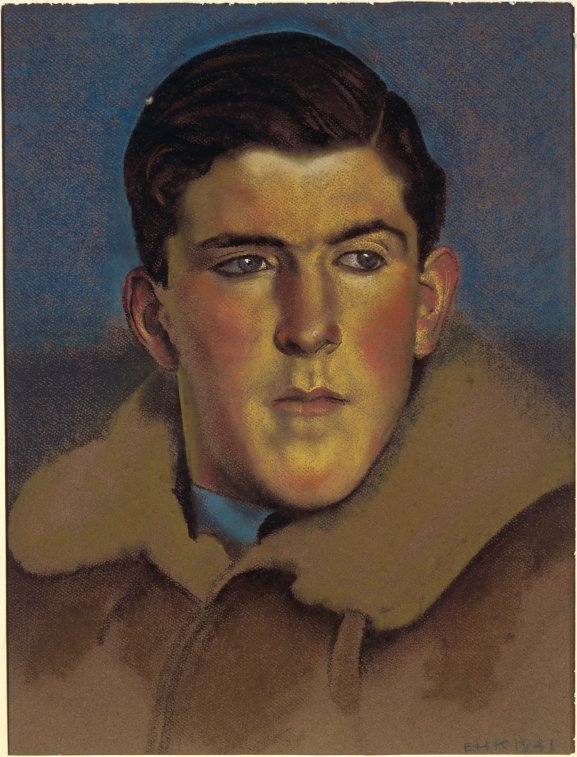

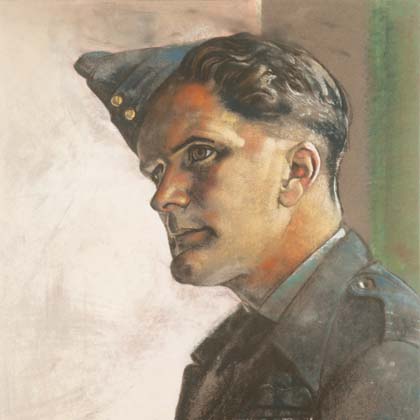

Kennington agreed to return as a war artist and the Committee offered him a commission to draw portraits of RAF personnel at a time when the Battle of Britain was at its fiercest and these men were often referred to as “fighting aces”.

The pastel portraits were sensitive depictions of the air force heroes and many were used as illustrations in Kennington’s 1942 book Drawing the RAF. There is a simplicity about these portraits but the underlying thought that these were some of the men who would fight for and save our country, was unmistakeable.

One must remember that the War Arts Committee would give Kennington a list of people who were to appear in his portraits. This caused a rift between Kennington and the Committee as Kennington believed that all the Committee wanted was portraits of senior officers and Kennington wanted to highlight some of the fighting men from the lower ranks. Once again Kennington threatened to walk away from his position as a war artist but he was such a great portraitist that he was talked out of his impending resignation by none other than the Chief of the Air Staff, Sir Charles Portal.

As he carried on with his portraiture commissions they were often exhibited at the National Gallery. Previously they had been lauded as great works of art but occasionally they received some adverse criticism, such as piece written by the art critic of the Sunday Times, Eric Newton, who wrote:

“…Eric Kennington goes on and on with his over-life-size portraits of supermen. They are strident things whose assertiveness almost hurts the eyes.’ But then he did concede: ‘They do look like men who are going to win the war. Some are positively frightening. Dropped as leaflets over enemy country, I can imagine them being as effective as a bomb…”

In November 1941, Eric Kennington was invited to Ripon, Yorkshire by Sir Percy Cleghorn Stanley Hobart, the General Officer Commanding of the 11th Armoured Division to sketch portraits of some of his men. Whilst there Kennington completed over twenty portraits of the men and also this small (29 x 38cms) oil on board portrait of his host. Many of the portraits Kennington did whilst at the Ripon barracks appeared in his 1942 book Tanks and Tank Folk and many featured in his solo exhibition held at the Leicester Galleries, London in September 1943

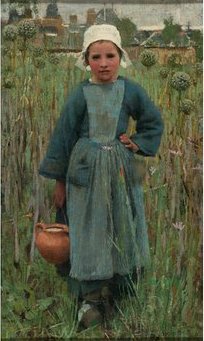

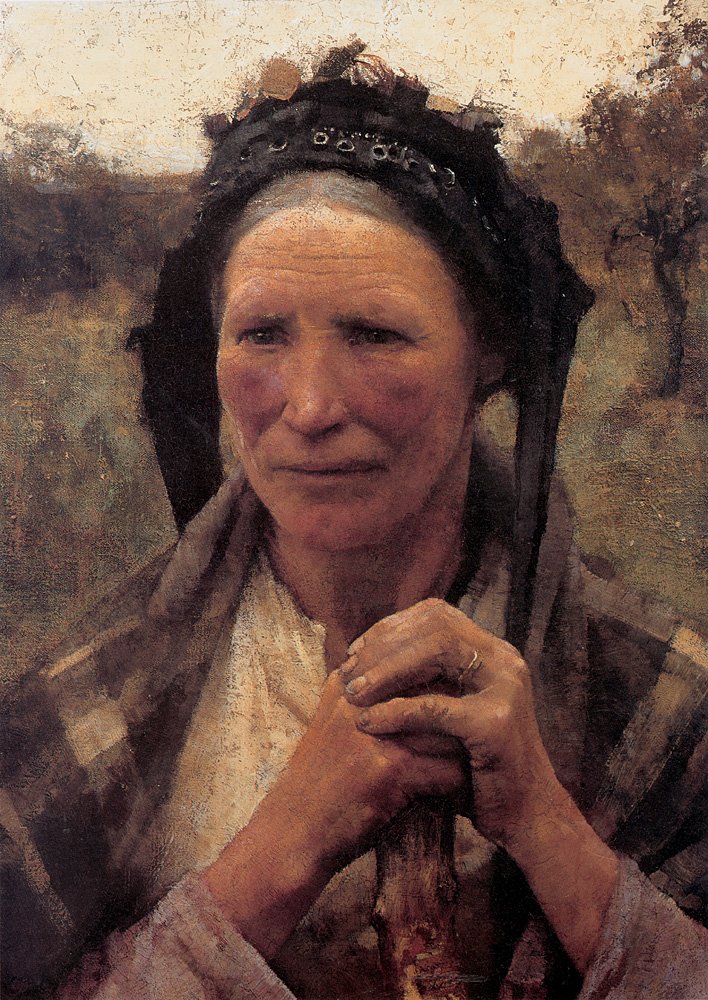

My final offering is a painting by Kennington which was used as one of the war posters in the series Seeing it Through. It was not of a fighting man or woman, but commemorated everyday heroism of normal people going about job in difficult and dangerous times. Kennington preferred not to use models for this type of work and in this work he used the woman herself as the model. It is of a young twenty year old woman, Mrs M.J. Morgan, who was a conductor on one London buses. She had become one of the first generation of female bus conductors employed by London Transport in November 1940. She’d only just started her job as a “clippie” when the bus she was assigned to was caught in the blitz. She became an instant heroine when she shielded with her own body two young children, and then helped passengers who’d been injured when the bus was riddled with shrapnel from a bomb exploding nearby.

Kennington remembered her well describing her:

“…like a Rubens Venus’ and she had a complexion that was ‘edible as a peach…”

Beneath the portrait of the bus conductor was a short verse by the novelist and humorist, Alan Patrick Herbert:

“…How proud upon your quaterdeck you stand

Conductor- Captain of the mighty bus!

Like some Columbus you survey the Strand

A calm newcomer in a sea of fuss

You may be tired – how cheerfully you clip

Clip in the dark with one eye on the street –

Two decks – one pair of legs – a rolling ship

Much on your mind and fat men on your feet !

The sirens blow, and death is in the air

Still at her post the trusty Captain stands

And counts her change, and scampers up the stair

As brave a sailor as the King commands.

A.P.Herbert

Eric Henri Kennington died in April 1960 aged 72. He is buried in the churchyard in Checkendon, Oxfordshire, where he was once the churchwarden and he is commemorated on a memorial in Brompton Cemetery, London..