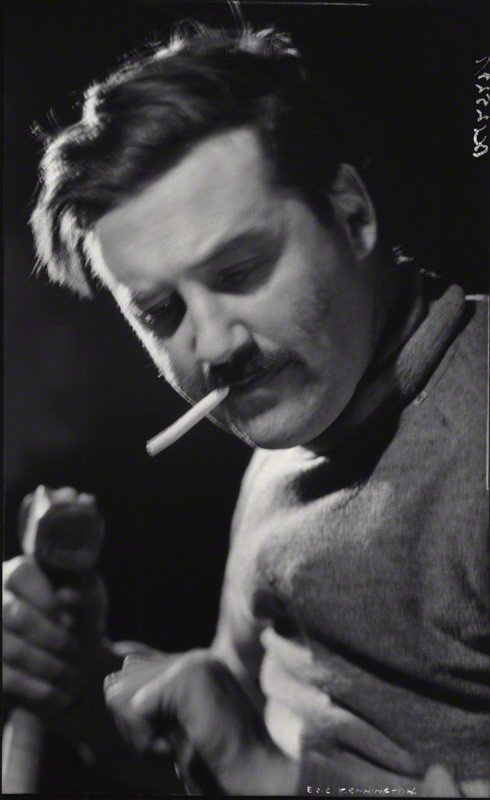

In my last blog I looked at the life and some of the paintings of Thomas Benjamin Kennington, the Victorian painter. Today, in the first of two instalments, I want to look at the life and art of his son Eric Henri Kennington, who was an early twentieth century sculptor and artist.

Eric was born in Fulham in March 1888. He was the second of two sons. His father was the Victorian artist Thomas Kennington and his mother, Elise Nilla Lindahl Steveni, was of Swedish origin. His mother died when Eric was just seven years of age.

Eric was born into a middle-class professional household and received the best education possible, attending St Paul’s School, London, one of the original nine British public schools and from there he enrolled at the Lambeth School of Art. He started exhibiting his works of art at the Royal Academy in 1908 and by the start of the Great War in 1914 he had gained a reputation as a skilful painter.

One of his pre-War paintings was entitled Costermongers (La cuisine ambulante) which was exhibited at the International Society in April 1914, and the work itself was actually bought by the then very famous society portraitist William Nicholson. It is now owned by the Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris. It is the depiction of street life in London and is a fascinating capture of the individual characters. The art critic of the Daily Mail wrote in the August 24th 1914 edition of the newspaper describing the scene as:

“…‘huge staring groups of life-size people, represented in a brutal airless way, though with a great deal of technical cleverness…”

and went on to acknowledge that they were protests against the “namby-pambiness’ of the usual group compositions..”

With the sale of the painting Kennington was able to set himself up in a studio in Kensington High Street.

The Great War broke out in Europe in July 1914 and in the next month, Kennington took himself down to the recruiting office which was close to his studio, off Kensington High Street, and enlisted with the 13th Battalion, The London Regiment, Princess Louise’s Own Kensingtons. He was sent to the Hertfordshire village of Abbot’s Langley where he did his three months of basic training before being sent to France in November 1914. His days fighting on the front line were numbered as in mid-January 1915 he suffered a wound to his left foot which resulted in the amputation of his middle toe and he was extremely lucky not to have lost the whole of his left foot through infection. He was discharged from the army as being unfit for duty.

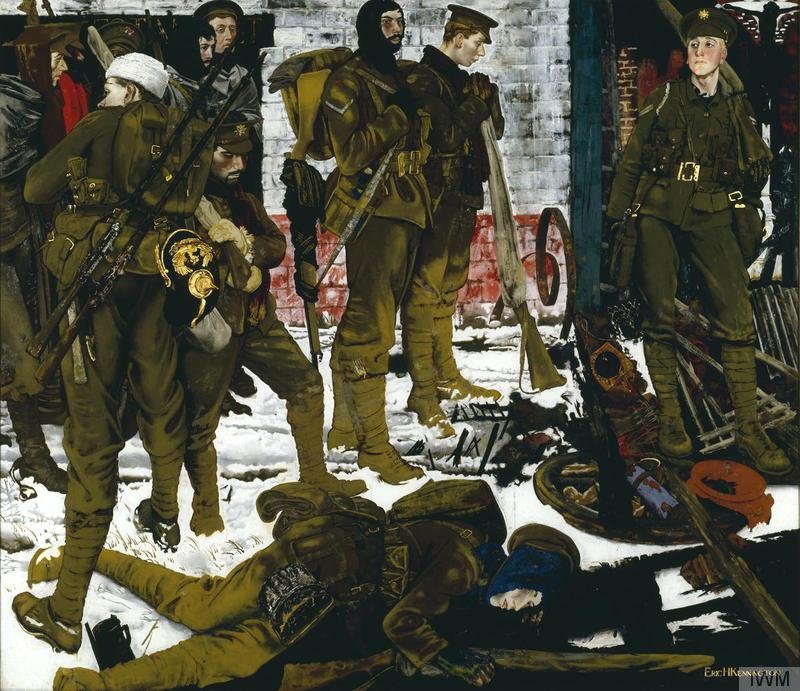

It was during his time convalescing throughout the latter part of 1915, firstly in London, then Liverpool, that he painted one of his most famous works of art. It was a portrait of some infantrymen entitled The Kensingtons at Laventie, Winter 1914, which is now housed in the Imperial War Museum, London. The painting is extremely large measuring 140 x 152cms. The picture is a complex reverse painting on glass, where exterior layers of paint are applied first, giving the oils a particular clarity.

In the painting, Kennington depicts part of his platoon standing around in a deserted street in Laventie, a small French village in the Pas-de-Calais region, close to the Belgium border. The village had been almost destroyed by shell fire. It is set in the winter of 1914 with snow on the ground. The soldiers in this painting were comrades from his unit, Platoon no. 7, C Company of the Kensingtons, and he has even included a portrait of himself in the scene. He is in the top left-hand corner wearing the balaclava. The men have arrived at the village after a long and tiring four days and four sleepless nights of duty in the trenches having had to endure continuous snowfall and temperatures at night which fell to twenty below freezing. It is a loose grouping of men, all but one standing. What is strange about their depiction is that no two men look in the same direction. The men seem disorientated and are awaiting their corporal to find out their next orders. Soon they were going to have to set off and endure a five-mile march to reserve billets, which were out of range of the German artillery.

The painting was first exhibited at the Goupil Gallery in 1916 and caused a sensation. The exhibition was in aid of the Star and Garter Building Fund charity. Kennington’s accompanying notes detailed the individual soldiers and their experiences. The notes about “Who is who” stated:

“…The portraits are of Private A. ‘Sweeney’ Todd (foreground) and (left to right) Private H Bristol in the red scarf, Private A. McCafferty carrying two rifles, the artist in balaclava, Private W Harvey, Private P A Guy, known as ‘Good Little Guy’, Lance-Corporal H Wilson in balaclava, Private M Slade resting both hands on his rifle and Corporal J Kealey…” .

Kennington did not complete the painting until December 1915 and sadly by this time, ninety per cent of the once 700-strong battalion, which he had arrived with in France twelve months earlier, had become causalities. Many had died or had been severely wounded during the battles of Neuve-Chapelle in March 1915, and particularly Aubers Ridge in May 1915..

The painting, when exhibited at the Goupil Gallery between April and June 1916, received glowing revues. Kennington was described by The Times art critic: :

“…the painter who knew how to properly portray the stoically enduring British Tommy’. For example,………: ‘He [Kennington] has painted the real war for us in all its squalor and glory…”

So impressed with the unemotional depiction of the hardships and endurance of the British soldiers whilst fighting on the Front, the War Propaganda Bureau, in June 1917, offered Kennington the chance to become an official war artist. He was sent off to France in August 1917, where he spent about seven months. In fact he was only supposed to be visiting the battlefields for one month but after the first month had expired, he didn’t want to return to England and simply refused to come back home. He would continually write to his employers stating that he needed to be on the battlefield so that he could “learn the war

One of his first paintings as an official War artist was entitled Gassed and Wounded which he completed in 1918 and can now also be found in the Imperial War Museum. The setting is the interior of a field hospital. Eric Kennington made many sketches when he was at Casualty Clearing Station at Tincourt, a village in the Picardy region, some thirty miles east of Amiens. This point in time when Kennington made these sketches was at the time the German air force was bombarding the English lines, prior to their last big offensive. In the painting we see wounded soldiers, who have been gassed, lying on stretchers. Look at the way Kennington has depicted the agony of the man in the foreground. He lies on the stretcher. His head is bound with bandages. His eyes which have been damaged by the gas are covered. His face is contorted and his mouth is open as he cries out in pain.

Eventually Kennington was persuaded to return to England in March 1918 Four months later a large selection of his pastel and charcoal drawings and watercolours were exhibited in an exhibition at the Leicester Galleries. The art critics and public alike were astounded by the quality of his work

The art critic and poet, Laurence Binyon wrote in the New Statesman:

“…Mr Kennington has a genius for reality. He has not only the gift of exact and faithful record, but the power of giving expression to the latent vehemence, energy and passion that make up the controlled strength of a man. If a foreigner wished to see the British soldier, he could not do better than see him with Mr Kennington’s eyes…”

Kennington, had his differences with the Ministry of Information and parted company in September 1918. He was not unemployed for long as in November 1918, he signed up with the Canadian War Memorial Scheme. This scheme was established by the newspaper magnate Lord Beaverbrook in 1916. His aim was to commission official war artists to paint the Canadian war effort. The official war art programme would eventually employ close to 120 artists, most of them British or Canadian, who created nearly 1,000 works of art. Eric Kennington went back to France in November 1918 as a temporary first lieutenant attached to the Canadian Army and he attached himself to the 16th Battalion Highlanders of Canada, part of the 3rd Infantry Brigade of the 1st Canadian Division.

(Originally known as “The Victims”)

Kennington remained in France between November 1918 and March 1919, during which time he made a series of over 40 studies of individual soldiers from the battalion who fought their last major battle of the war in October 1918. The next painting I am showing you is one entitled The Conquerors and featured men from the battalion of soldiers Kennington was assigned to as a war artist. This was not the original title of the work as when the painting was shown in an exhibition in Canada, it was entitled The Victims but there was an objection to that title from the battalion’s commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Cy Peck, Kennington who wanted it to be changed and be renamed The Conquerors. Cyrus Wesley Peck objected to the title “The Victims” as it was a somewhat defeatist title for the work of art and so it was changed to a more acceptable title, The Conquerors. The painting depicts kilted Canadians of the 16th Battalion, marching through a battlefield littered with debris and informal graves. Look at the faces of the soldiers. Some have normal skin tones whilst others look much paler and these may represent the deceased. The painting is housed in the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa.

The Conquerors was exhibited in Ottawa during the summer of 1920 and it was later returned to London where, in October and November of that year, it appeared at Kennington’s solo exhibition at the Alpine Club gallery in London. Whilst Kennington was present at the exhibition he met and was befriended by T.E.Lawrence the British archaeologist, military officer, and diplomat. Lawrence bought two of Kennington’s sketches depicting soldiers. The intrepid Lawrence was a great influence on Kennington’s art and he even persuaded Kennington to come out to the Middle East to draw personalities who appeared in his account of the war with the Ottoman Turks that he was writing at the time, and which was eventually published as The Seven Pillars of Wisdom. The book was the autobiographical account of the experiences T.E. Lawrence had, while serving as a liaison officer with rebel forces during the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Turks which lasted two years from 1916 to 1918. T E Lawrence soon became known as Lawrence of Arabia.

One such portrait was completed by Kennington in 1920 entitled Muttar il Hamoud min Beni Hassan who was one of Lawrence’s s chosen bodyguards. This pastel on brown paper was painted by Kennington whilst he was at a war camp in Western Arabia. Lawrence had wanted Kennington to go out to Arabia and come back with some portraits which could be used as illustrations for his autobiography but strangely he would not let Kennington read the book before he set off on his Arabian journey. On returning back to London Kennington gave Lawrence his sketches and paintings. Lawrence was delighted saying:

“…I first saw one and then another of the men whom I had known and at once I learned to know them better. This may point indirectly to the power of the drawings and it points without contest to their literary completeness. There is quite admirable character here…”

Another portrait by Kennington used in Lawrence’s autobiography was Abd-el-Rahman, a pastel on green-toned paper, which he completed in 1921. Abd-el-Rahman was mentioned in Chapter LXXI of the book as Lawrence recalls:

“…I enrolled Showakh and Salem, two Sherari camel-herds, and Abd el Rahman, a runaway slave from Riadh, now freedman of Mohammed el Dheilan, the Toweihi…”

On Kennington’s return home he exhibited the sketches and paintings from his Arabian trip at the Leicester Galleries in London and the portraits of Arabs became known as the ‘Kennington Arabs’. The illustrations which Kennington worked on for Lawrence did not appear in the first edition of the book published in 1922 but four years later in 1926, in the next edition of the autobiography Kennington’s illustrations appeared along with those done by other well-known artists of the time such as Augustus John, Paul Nash and John Singer Sargent

Kennington also produced a bust of Lawrence in 1926. It was modelled partly from life and partly from drawings he made in December 1926. It was also chosen by Lawrence’s mother and brother for the Crypt of St Paul’s. Kennington made three further casts of this head in bronze or brass, one of which can be found in the music room at Lawrence’s cottage, Clouds Hill, Moreton, Dorset. Clouds Hill is an isolated cottage near Wareham, Dorset which Lawrence initially rented in 1923 but then bought it in 1925. Lawrence himself loved the bust saying that it was:

“…magnificent; there is no other word for it. It represents not me but my top moments, those few seconds when I succeed in thinking myself right out of things…”

Sir William Rothenstein, an English painter, printmaker, draughtsman and writer on art. who was best known for his work as a war artist in both world wars and as a portrait artist wrote about Kennington’s relationship with T E Lawrence. He wrote:

“…‘Kennington was devoting himself to Lawrence’s glorification – for him Lawrence was the perfect man who could do no wrong…”

by Eric Kennington

In 1924, Eric Kennington designed the War Memorial which can be seen in Battersea Park to commemorate the 24th London Division.

In the second part of my story of Eric Kennington I will look at his life between the world wars and also the paintings he completed as a war artist during the Second World War.

Such a fascinating post, beautifully written and illustrated, thank you very much. I also loved the post about his father Thomas. I am learning so much from your blog and appreciate all the work you do on it.

Karen

http://www.dogandpetpaintings.blogspot.co.uk

>

Fascinating. I hadn’t heard of this artist before. The heads of Lawrence’s bodyguards are amazing

I know Kennington only from him having worked with TEL. This helps so much to put him in perspective. Thank you.