In Dusseldorf, on February 2nd 1827, Christine Achenbach gave birth to her fifth child, her son Oswald. His father, Hermann, was a man-of-all-trades, a one-time manager of a metal factory, a beer brewer, an innkeeper and finally a bookkeeper. Oswald was destined, like his brother Andreas, who was almost twelve years older than him, to become one of the great nineteenth century German landscape artists and an important representative of the Dusseldorf School of Painting. Their painting style was so alike that they were often jokingly referred to them as the Alpha and Omega of landscape painting.

When Oswald was still a young child the family moved to Munich where he attended primary school. During Oswald’s early childhood, the family moved to Munich where he attended primary school for a short period. In 1835, the family moved back to Dusseldorf and Oswald followed the artistic path of his brother and was enrolled in the elementary class of the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf (Dusseldorf Art Academy). In fact, he should not have passed the entrance criteria for the school as its rules laid down a minimum entry age of twelve. However, he was given a place and remained there until 1841. There is no record of why the academy relaxed the age criteria but it could well have been that they recognised a budding artist who had probably received some artistic tuition from Andreas. All that is known about his six years at the academy is gleaned from his sketchbooks which were full of nature sketches from the area around the city.

There is no certainty as to why Oswald left the Academy at the age of fourteen but it is thought that he was unhappy with the very demanding Academy teaching. It was not just the Dusseldorf Academy which had their rigid formal academic training, the same was happening in all the European Art Academies and all fought hard to maintain their formal approach. Where the Academies held the ‘whip hand’ was the fact that they organized the big art exhibitions, at which artists were primarily able to sell their work. Artists who dared oppose the Academic style were unable to have their works exhibited, which meant their opportunity to sell their paintings was curtailed. However, artists were not prepared to bow to such pressure and soon began to make their feelings known.

After leaving the Academy, Oswald Achenbach joined two associations: the Verein der Düsseldorfer Künstler zur gegenseitigen Unterstützung und Hilfe (association of Düsseldorf artists for their mutual support and aid) and like his brother, the Malkasten, which was founded on 11 August 1848 with Andreas Achenbach as one of the original signatories of the founding document. These Associations jointly staged plays, organized music evenings and staged exhibitions. At many of these events, Oswald took an active part, directing, playing or staging plays. He was a staunch supporter of the Malkasten and remained a member until the end of his life.

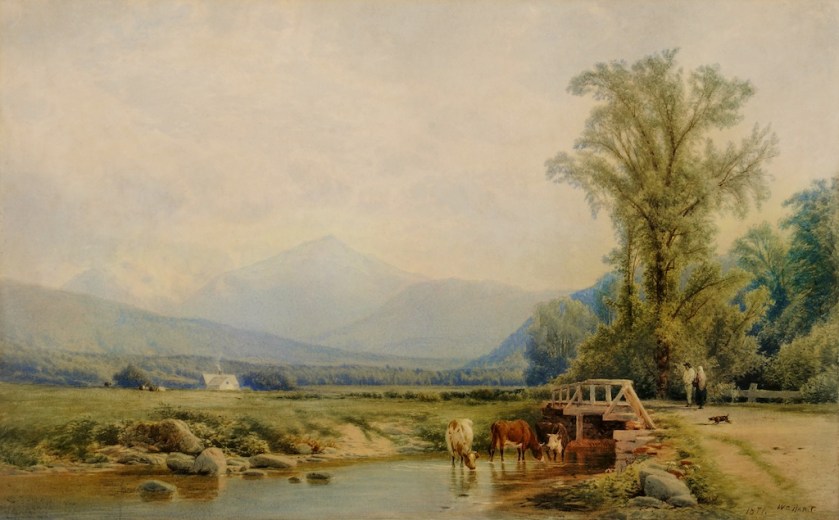

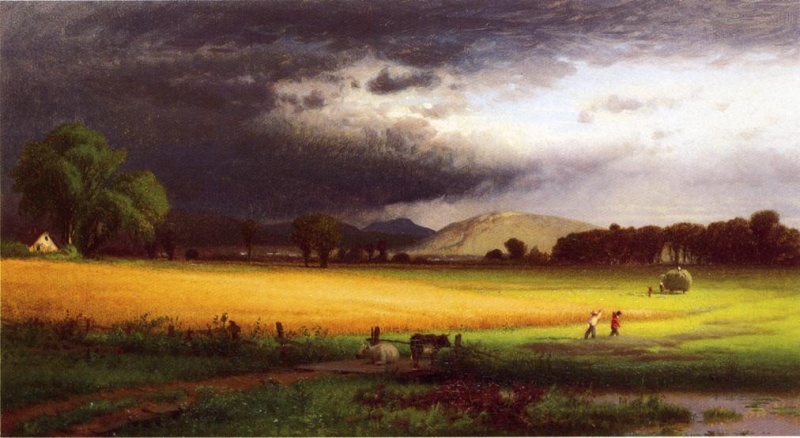

In 1843, sixteen-year-old Oswald Achenbach began a prolonged journey of discovery which lasted several months. He travelled through Upper Bavaria and the North Tyrol of Austria, and arrived in Northern Italy, all the time sketching the landscapes he encountered. He returned to Italy on many occasions and Oswald is best remembered for his Italian landscape works. Despite Oswald’s dislike of how art was taught at the Dusseldorf Academy, the subject matter and the techniques he employed in his early landscape works were heavily influenced by the ideas being taught at the art academies of the time. Art historians confirm that the influence of Johann Wilhelm Schirmer, a tutor at the Dusseldorf Academy and Carl Rottman, the German landscape painter who completed many Italian landscape works, can be seen in Oswald Achenbach’s paintings. In Oswald Achenbach oil studies for his paintings during his Italian travels, he adhered very closely to the nature of the landscape and concentrated on the details of the typical Italian vegetation. In his early works, he showed less interest in architectural motifs and any figures in his depictions played a much smaller role than they would in his later, more mature work.

Around 1847, Oswald received a commission to contribute some lithographs of his paintings, sketches, and other works for the satirical journals, Düsseldorf Monathefte and the Düsseldorf Monatsalbum. These journals were published by Heinrich Arnz, a well-known bookseller and printer who co-owned the Arnz & Co. with his brother Josef. Heinrich had a son, Albert, five years younger than Oswald. He was an artist who, like Oswald, studied at the Dusseldorf Academie and would often accompany him on some of his Italian trips. Heinrich Arnz also had a daughter, Julie, the same age as Oswald Achenbach and after a brief courtship the pair became engaged in 1848, and three years later, the couple married on May 3rd 1851. Between 1852 and 1857 the couple had four daughters, followed by a son in 1861. Their son, Benno von Achenbach, went on to become the founder of the carriage driving system named after him. In 1906 he became head of the Neuer Marstall in Berlin, which housed the Royal equerry, horses and carriages of Imperial Germany and in 1909, William II awarded him the hereditary nobility for his services to equestrian sport.

Not now having any connections with the Dusseldorf Academy, Oswald Achenbach had problems in trying to exhibit and sell his artwork. However, in 1850 he found an outlet in the form of the newly founded Düsseldorf gallery of Eduard Schulte. The gallery exhibited the works of artists who were independent of the Academy and as such, played an essential role in Achenbach’s early economic success. The Eduard Schulte gallery became one of the leading German galleries and later expanded, opening galleries in Berlin and Cologne.

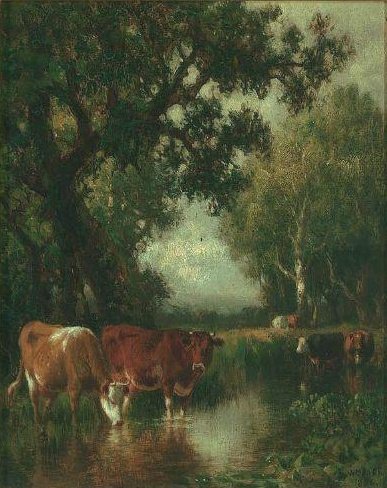

Whether by mutual consent or just fate but the two landscape painting brothers Oswald and Andreas seemed to choose different areas of Europe to depict in their paintings. The older brother Andreas although a large amount of his work was focused on seascapes and maritime depictions, he preferred his landscapes to focus upon the countryside of Northern Europe and Scandinavia, whereas Oswald preferred to produce depictions of Southern Europe, especially Italy.

Oswald’s first major painting venture to Italy came in the summer of 1850. His companion for the adventure was Albert Flam, a German landscape painter, who had been taught by Andreas Achenbach and, like the Achenbach brothers, had been a student at the Dusseldorf Academy. They travelled to the French Cote d’Azur seaside town of Nice and then crossed over the Franco-Italian border to Genoa, the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and then they journeyed north to Rome. The pair went off on daily sketching expeditions to the Roman Campagna which was so popular with earlier landscape artists who were inspired by its beauty. Rome was a great place for artists to meet each other and during his stay in Rome Oswald met many including the Swiss Symbolist painter, Arnold Böcklin, Ludwig Thiersch, the German painter known for his mythological and religious subjects and especially his ecclesiastical art, and the landscape painter, Heinrich Dreber with whom he spent a long time in Olevano Romano, a commune which lies about 45 kilometres east of Rome. All artists tackle landscape painting differently and Ludwig Thiersch commented on how his friends differed. He said that Dreber drew elaborate pencil sketches, Böcklin simply let himself experience the environment and recorded relatively little in his sketchbook, while Achenbach and Flamm both painted oil studies outdoors. For Oswald Achenbach it was all about colour and achieving the correct tone by layering the paint. Form and the distribution of light and shadow was also very important to him, but less so was detailed topographical accuracy.

By the start of the 1850’s, Achenbach’s paintings were well-known internationally. In 1852, aged 25, the Art Academy in Amsterdam had admitted him as a member. More fame came his way when several of his works were displayed at the Exposition Universelle of 1855 in Paris, all of which were praised by the art critics and the public alike. In 1859, he received a gold medal at that year’s Salon Exhibition in Paris. In 1861 he was granted an honorary membership to the St Petersburg Academy and in 1862 he was bestowed membership of the Art Academy of Rotterdam.

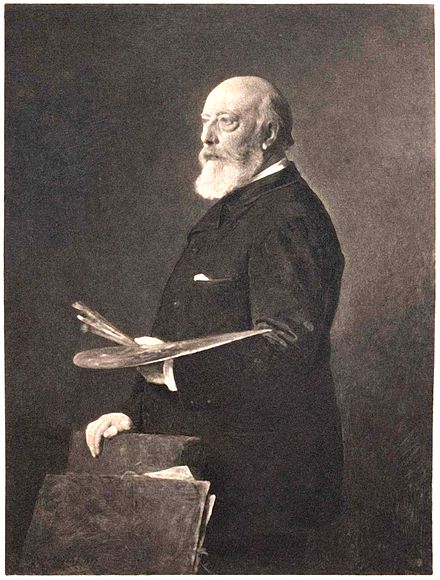

Despite leaving the Academy due to his opposition to the Academy’s method of teaching art, in March 1863, Achenbach became the Professor for Landscape Painting at the Düsseldorf Academy. This was a great honour and it signified an elevation in his social standing as well as financial security. It would also look to be a volte-face to his earlier opposition but the reason for him accepting the post could have been due to the departure of the director of the academy, Friedrich Schadow, four years earlier and the fact there had been conciliation between the Academy and the independent artists. The title, Knight of the Legion of Honour, was bestowed on Oswald by Napoleon III in 1863. Many more international honours followed. Oswald Achenbach continued to have his work exhibited at the Salon between 1863 and 1868

In the following years, Achenbach continued to make more trips and his last major trip was to Italy. It began in the early summer of 1882 and he visited Florence, Rome, Naples, and Sorrento. In 1884 and 1895 he took trips to Northern Italy. He had planned a trip in 1897 to Florence but cancelled it due to illness.

Oswald Achenbach died in Düsseldorf on February 1st 1905, one day before his 78th birthday. He was buried in the city’s North Cemetery.

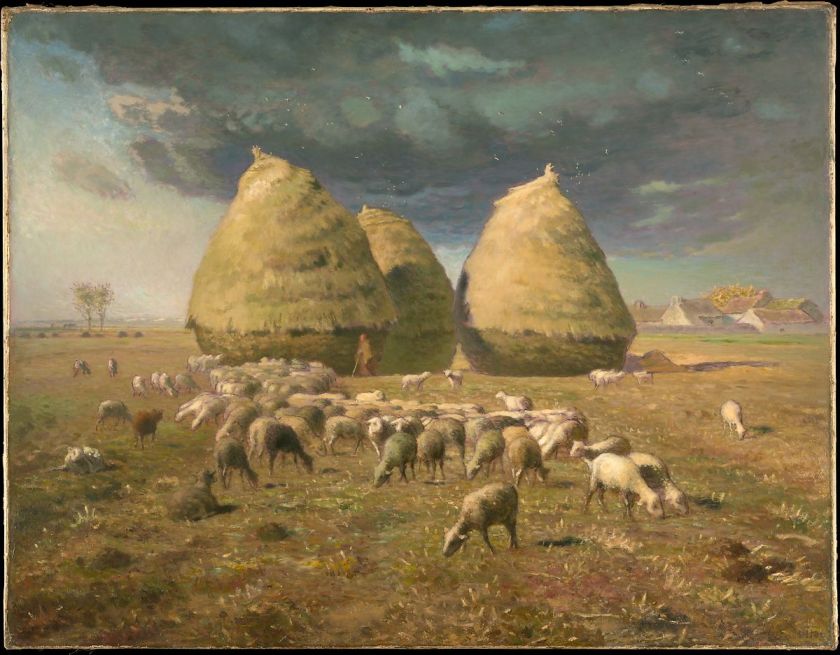

This was a major commission and Lhermitte was able to use the many drawings of peasant life he had already completed. In the introduction the author wrote:

This was a major commission and Lhermitte was able to use the many drawings of peasant life he had already completed. In the introduction the author wrote:

An example of this is the preliminary sketch of the reclining man, dressed in brown, we see at the bottom left of the Fête Galante painting. This sketch can be found at the Ackland Art Museum, which is part of the University of North Carolina, at Chapel Hill.

An example of this is the preliminary sketch of the reclining man, dressed in brown, we see at the bottom left of the Fête Galante painting. This sketch can be found at the Ackland Art Museum, which is part of the University of North Carolina, at Chapel Hill.