In this blog I am returning to an artist I talked about almost nine years ago. My artist today is Bernardo Bellotto who was born in Venice on May 22nd 1722. He was the third-born child of Lorenzo Antonio Bellotto and Fiorenza Domenica Canal, who was the eldest of three sisters of Giovanni Antonio Canal, better known to us as Canaletto. Bellotto’s started his initial artistic training at the age of fourteen when he worked in his uncle’s workshop. Two years later, at the age of sixteen, Bellotto became a member of the Fraglia dei Pittori (Venetian painters’ guild). Bellotto trained in Canaletto’s studio and would help him to satisfy the growing demand for Venetian scenes. Bellotto would later point out the family connection by signing some of his works ‘Bernardo Canaletto’ or ‘Bellotto de Canaletto’.

In around 1741, he and his uncle, Canaletto, took a trip along the Brenta canal to Dolo and Padua and during this time the two painters amassed a number of sketches which would be later transformed into completed oil paintings. On October 5th, 1741 a marriage contract was drawn up by Bellotto and his future father-in-law Giambattista Pizzorno, for permission for the artist to marry Elisabetta Pizzorno. On November 5th 1741, Bellotto married Elisabetta Pizzorno at Il Redentore church in Venice. A dowry of 850 ducats was agreed to be paid by the bride’s family to the groom at the time of marriage. Their first child, Lorenzo, was born on October 15th, 1742. A further insight into Bellotto’s life around this time is a document submitted by his mother in which she declares that the family has been abandoned by her husband Lorenzo and that the only goods in her possession are those procured for her by Bernardo who, with his work, maintained her and his brother Pietro, both of them being resident in Bernardo’s home. The brother Pietro Bellotto, who was also an artist, also declared before the same notary to have learned the art of painting from Bernardo. In order to continue living with his brother and improve in his profession Pietro signs a pledge to give him one hundred and twenty ducats a year.

In 1742 Bellotto set off on a painting trip and travelled extensively around the Northern Italian cities, stopping off at Florence and Lucca and during each stop he would complete a verduta of the place. A verduta is a highly detailed, usually large-scale painting of a cityscape or some other vista. These painting were very popular with the foreigners who travelled around Italy on their Grand Tour and wanted to bring home something to remind them of the places they had visited.

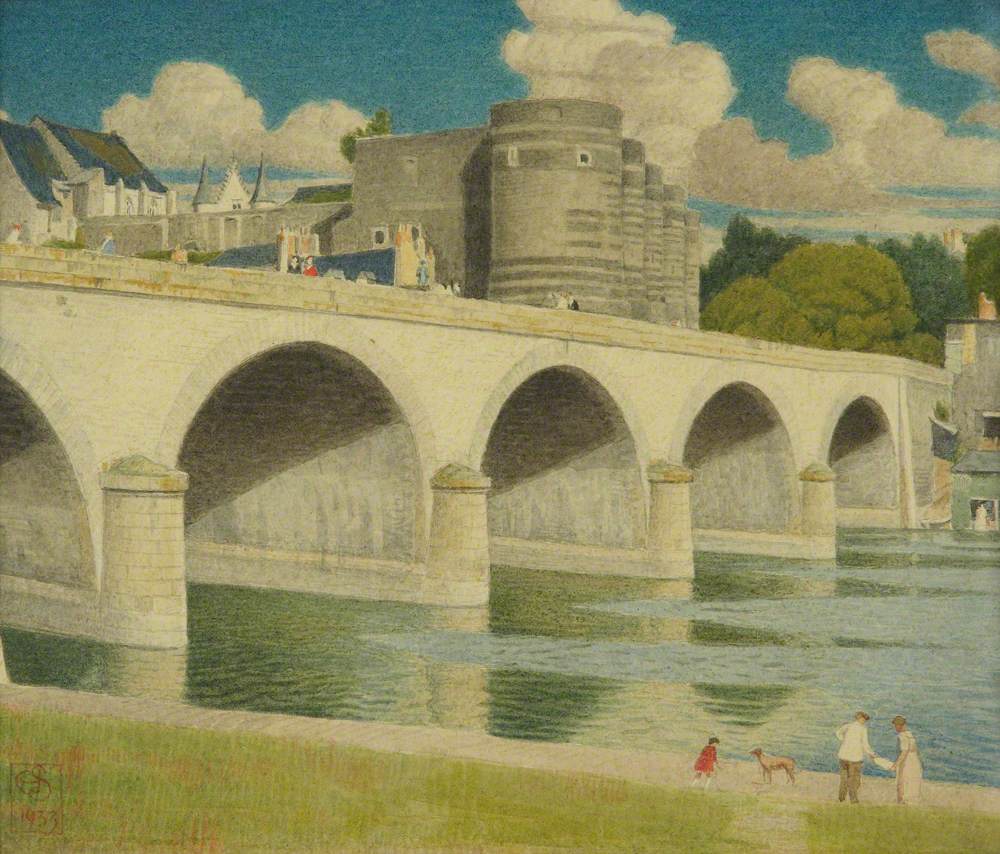

Bellotto made a number of painting trips to Lombardy and during a stopover and around 1746 whilst in Turin he painted a view of the city. It was entitled The Old Bridge over the River Po, Turin and it was a commission he received from Charles Emmanuel, King of Sardinia and Duke of Saxony. If you look closely to the extreme left of the painting you will see an artist sitting before his easel which was presumably a reference to himself. This and his other Turin depictions were large measuring 127 x 171cms and they were, as this was, sweeping panoramic views with such exquisite architectural detail of the brick tower and the bridge in the foreground. Look how well he has used light and colour to portray the reflections on still water and the hint with regards the moving currents. Bellotto eventually arrived in Rome where he studied study architectural and topographical painting and would remain in the Italian capital until 1743 at which time he journeyed back home to Venice.

In May 1746 Bellotto’s uncle Canaletto left Venice for England where his paintings were in great demand. A year later Bellotto also left Venice. His destination was Germany and the city of Dresden where he hoped to forge a career and avail himself of some lucrative commissions. His desire for commissions materialised within a year of his arrival as he became the court painter at the court of Friedrich August II, Elector of Saxony and soon Bellotto was the highest paid artist at the Saxon court. The following decade was to be Bellotto’s most successful.

The city of Dresden and the outlying districts, such as the villages of Pirna, and Königstein with its magnificent Königstein hilltop fortress, all of which offered Bellotto the chance to paint beautiful cityscapes and rural landscapes. In all, Bellotto completed thirty different paintings for the Elector. Fourteen depicting views of the city of Dresden and its wonderful buildings, eleven of Pirna and its surrounding rural landscapes and five of the magnificent Königstein fortress.

The city of Dresden and the outlying districts, such as the villages of Pirna with the nearby Sonnenstein Castle, and Königstein with its magnificent Königstein hilltop fortress, all of which offered Bellotto the chance to paint beautiful cityscapes and rural landscapes. In all, Bellotto completed thirty different large scale paintings for the Elector, each between two and three metres wide. Fourteen depicting views of the city of Dresden and its wonderful buildings, eleven of Pirna and its surrounding rural landscapes and five of the magnificent Königstein fortress. The finished works were to be hung in the royal painting gallery in the Stallhof, which forms part of the Royal Palace in Dresden. Bellotto’s depictions of the city of Dresden were remarkable for their topographical meticulousness, mathematical perspective and the way in which he portrayed the way the light played on the various architectural structures. The way he handled the light was truly remarkable.

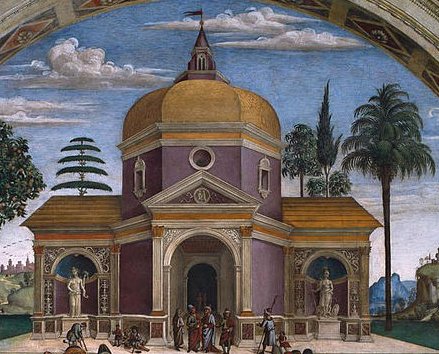

This painting is part of the NGA Washington. This depiction by Bellotto of the Fortress of Königstein is one of five large canvases, commissioned by Augustus III in the spring of 1756 but never delivered, depicting the renovated medieval fortress in the countryside near Dresden.

Bellotto having received the royal commission to complete thirty large scale paintings of Dresden, Pirna and Königstein was proceeding well with the commission. The Elector’s commission had enabled Bellotto to live a life of luxury. He had an seven reception rooms in his Dresden apartment which was awash with luxurious furnishings, Venetian mirrors and fine wallpapers and fabrics. Life could not have been better. What could possibly go wrong? The answer to that question was the Seven Year War, which broke out involving all the main European “players”. The Prussian army invaded Saxony and entered the city of Dresden and Augustus, the Elector of Saxony and Bellotto’s patron fled the city and barricaded himself in at the Königstein fortress for several months before escaping to Warsaw. Bellotto left Dresden and his luxurious home and went to Pirna.

This view from the south of Königstein includes several buildings within the fortification: the southern end of the Brunnenhaus facing us to the left, the Georgenburg oblique behind it, and the Magdalenenburg in the foreground

In 1758 Bellotto and his sixteen-year-old son obtained passports to travel to Bayreuth from where he completed an onward journey to Vienna.

Shortly after his arrival in Vienna, Bellotto received a couple of private painting commissions. One was from Prince of Liechenstein and one from Wenzel Anton, the Prince of Kaunitz who was also chancellor to Empress Maria Theresa. Not only were they lucrative commissions it gave Bellotto a chance to receive a thirteen painting commission from the Empress herself. The commission tasked the artist to complete six depictions of the city of Vienna and seven much larger panoramic views of Schönbraun and Schloss Hof imperial palaces and their gardens.

For the two years Bellotto was in Vienna with his son he worked non-stop producing paintings for the Empress’ commission and other commissions for members of her court. This phenomenal output can also be put down to the help he received from his son Lorenzo. The resulting depictions were amazing and offered to serve as testimony of Vienna’s imperial magnificence

In 1761, after almost two years in Vienna, Bellotto left the city and travelled, not to Dresden where his wife and daughters lived, but to Munich. This could have been because of the on-going troubles with the Prussian invaders. He had been given authorisation to visit the German city through a letter from Empress Marie Theresa to her cousin Maria Antonia, the Princess of Bavaria, who had fled from Dresden since the Prussian siege. Once there Bellotto was commissioned to paint panoramic views of Munich and the Baroque Nymphenburg Palace in the western suburbs of the city, which was Maria Antonia’s birthplace and summer residence.

At the end of 1761 Bellotto returned to his home Dresden to find it devastated during the Prussian invasion. Worse, was the fact that he found himself in great financial difficulty arising from the death of two of his major patrons, Augustus III, Elector of Saxony and King of Poland and Count Heinrich Bruhl, the prime minister of Saxony in 1763. Their deaths and his financial situation made Bellotto melancholic and it was around this time that he painted the Kreuzkirche which now lay in ruins. It had been partially destroyed during the Seven Year War, at a time when Bellotto had been forced to flee the city. The painting is entitled View of the Kreuzkirche in Ruins and was completed by Bellotto in 1765. The Kreuzkirche is the oldest church in Dresden and, during the conflict, was shelled by Prussian artillery. The building was set ablaze and finally collapsed. The church tower, though damaged, remained standing. Work commenced on the reconstruction of the church and it was decided to preserve the original tower. Unfortunately, in June 1765, with the construction of the new church already under way, the greater part of the tower collapsed. The painting is a good example of how Bellotto unique, capacity to capture the spirit of an event. His depiction of the ruin is an unusual one for it is not an ancient ruin as far as the artist was concerned. It was a relatively new one as the destruction had only occurred five years earlier. Bellotto had completed a work depicting the great church some years earlier (see painting earlier in the blog). However, in this work, we see are the jagged remnants of the church rear up skywards. The cleanliness of the once beautiful church has gone. There is nothing clean about the church now. The scene before us is just a mass of noise and dirt. It is a chaotic scene which we find hard to believe that it could ever be put back to its former glory. The Church, as the body of Christ, has been violated all over again and the civic wounds of the German city have been violently opened for all to see. This is the price to be paid when once we set forth to war. In the painting we see many of Dresden citizens. Close to the ruins we can just make out craftsmen as they start their preparations to rebuild the once –beautiful edifice. On the periphery we see men and women dressed in their best clothes staring at the ruin. For them it was just a day out to visit the site where the destruction had taken place. For them it was just blatant voyeurism.

……………………………….to be continued.

![[Photo Credits: tyle_r]](https://www.visittuscany.com/shared/visittuscany/immagini/blogs/idea/4691713878_c6afb30368_z_wp6_8309.jpg)

![[Frieseke_Frederick_C_The_Garden_Parasol.jpg]](https://mydailyartdisplay.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/3712b-frieseke_frederick_c_the_garden_parasol.jpg)