In March 2023 I took you on a Japanese journey The Tokaido Road Trip and today I want you to join me on another such voyage of discovery through a series of ten Japanese woodblock prints in ink and color on paper made by Japanese artist Utagawa Kuniyoshi, one of the last the great Masters of ukiyo-e. Kuniyoshi was born on 1 January 1st 1798, the son of a silk-dyer, Yanagiya Kichiyemon. It is thought that he helped in his father’s business as a pattern designer, and those days helped to influence him some with regards to his rich colour usage and textile patterns in his prints

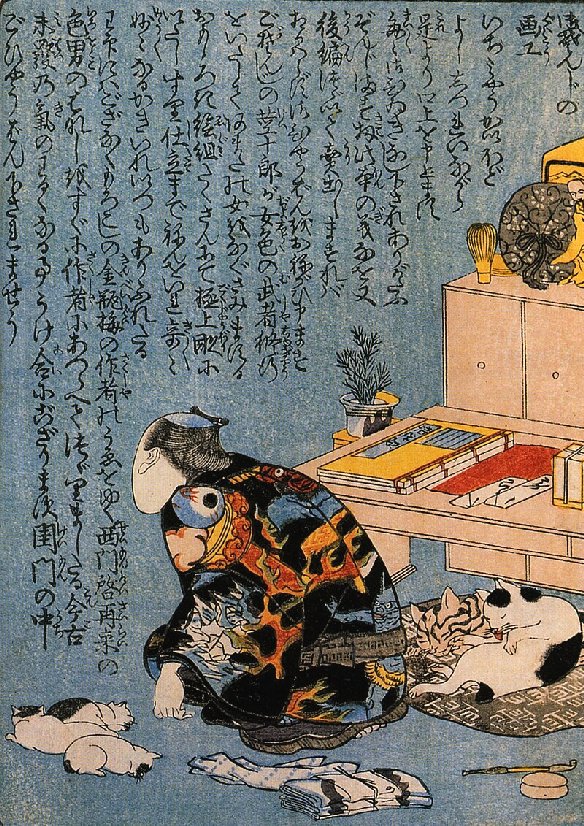

Self-portrait of Utagawa Kuniyoshi from the shunga album Chinpen shinkeibai, (1839)

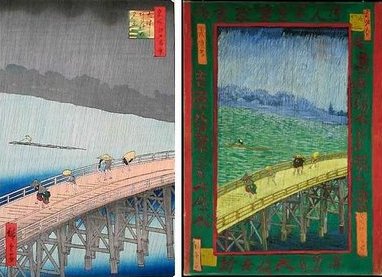

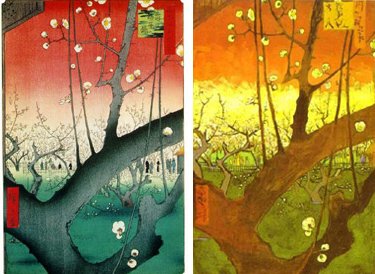

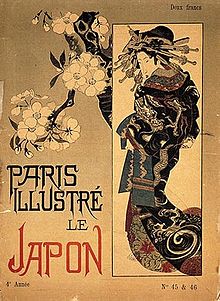

The ukiyo-e movement came to prominence in Japan between the 17th and 19th century. It was a form of art and one of the first times in Japanese history when art ended the adherence of social class and developed into an art form that appealed to the lowborn, who had money, as well as the rich aristocrats.

The Ghost of Asakura Togo, Woodblock Print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi

The subjects most found in these woodblock prints were travel, beautiful prostitutes, and kabuki actors, the 19th century Japanese equivalent of movie stars. Many of his popular prints were often not really something that the aristocracy would want to display in their residences, but such depictions as in his print, The Ghost of Asakura Togo, were just the thing that appealed to everyday Japanese urbanites who were searching for some excitement in their lives.

The Story of Nichiren

The portrait of Nichiren Daishonin was painted in the 14th-15th Century, and is kept at Nichiren Shu’s Head Temple, Kuon-ji.

This is the story of Nichiren Dashonin, a Japanese Buddhist priest and philosopher who lived in the thirteenth century and it was his controversial teachings which form the basis of Nichiren Buddhism, a branch of Mahayana Buddhism. Nichiren was born on February 16th 1222 and died on October 13th 1282. Nichiren, also known as Koso, was a Buddhist priest who had various miracles attributed to him and who founded the Nichiren sect of Buddhism, of which Utagawa Kuniyoshi was an adherent.

It was his controversial declaration that only the Lotus Sutra, which is regarded as one of the world’s great religious scriptures and most influential texts contained the highest truth of Buddhist teachings suited for the Third Age of Buddhism. He maintained that the sovereign of Japan and its people should support only this form of Buddhism and eradicate all others. Nichiren on three occasions remonstrated with the government, underlining his wish to guide people with ‘the Lotus Sutra’. However, on each occasion his pleas were rejected.

For twenty years between 1233 and 1253 Nichiren engaged in an intensive study of all of the ten schools of Buddhism which were prevalent in Japan at that time as well as the Chinese classics and secular literature. During these years, he became convinced of the pre-eminence of the Lotus Sutra and in 1253 returned to the temple where he first studied to present his findings. Here Nichiren introduced his teachings supporting a complete return to the Lotus Sutra as based on its original Tendai interpretations arguing that the people and their leaders who followed this form of Buddhism would experience peace and prosperity whereas rulers who supported inferior religious teachings invited disorder and disaster into their realms. However, his teachings angered Kamakura Shogunate and he experienced severe persecution and was exiled.

In 1831, Utagawa Kuniyoshi received a commission to produce a set of prints in remembrance of the 550-year anniversary of the death of Nichiren. The set was known as the Sketches of the Life of the Great Priest or Concise Illustrated Biography of Monk Nichiren.

Tōjō Komatsubara, Eleventh day of Eleventh month, 1264 by Utagawa Kuniyoshi

Tōjō Kagenobu, a steward of Tōjō Village in the Nagasa District of Awa Province in Japan was a passionate believer in Nembutsu, a fundamental devotional practice in the Pure Land school of Buddhism, which Nichiren had criticised ten years earlier. Tōjō Kagenobu was so infuriated by Nichiren’s severe criticism of the Pure Land (Jōdo) school that he attempted to have Nichiren seized. For this reason, he had harboured hatred for Nichiren and watched vigilantly for an opportunity to kill him. On November 11th, 1264, while Nichiren was travelling to Komatsubara, the home of his disciple, Kudo Yoshitaka. It was following his return to Awa, the year after he was pardoned from his exile to Itō on the Izu Peninsula. Tojo Kagenobu saw his chance to eliminate Nichiren. He and hundreds of his warriors, including horsemen and swordsmen, ambushed Nichiren at Komatsubara in the Awa Province in November 1264. In the depiction we see Nichiren holding up his mala (rosary), with its sparkling crystals which confused his attackers. Nikkyo, his student and disciple, is seen in the background, crouching. During the bitter fighting, two of his followers were killed and although Nichiren received a sword cut upon his forehead and a broken left hand, he managed to escape. The incident became known by the Nichiren Budhists as the “Komatsubara Persecution“. Tojo Kagenobu, who had led the attack is said to have gone mad and died within three days of this incident.

Nichiren Prays for Rain at the Promontory of Ryozangasaki in Kamakura in 1271

Japan experienced a major drought in the summer of 1271. The government asked Ninshō, a Japanese Shingon Risshu priest and the founder of the Gokuraku-ji, a Budhist temple in Kamakura, to conduct rain rituals. Nichiren, then only a lowly monk, disparaged Ninshō’s supporters, venturing that even he would follow Ninshō if he made it rain in a week. Nichiren was proved right as it did not rain, and he took advantage of the challenge to take on new followers for himself. In the woodblock print we see Nichiren as he prays for rain and is immediately rewarded with a downpour. This event takes place in Kamakura in 1271. The print itself is viewed as the second-greatest design in this famous series. Before us we have a dramatic depiction – the drama in the the heavy downpour, the drama in the waves and drama in Nichiren’s acolytes as they look on, astounded by the miracle they have witnessed. The umbrella at the top of the scene extends into the upper margin and is often trimmed.

Nichiren Saved from Execution at Takinoguchi in Sagami Province

Nichiren’s incessant attacks on the other Buddhist schools led to Hōjō Tokimune, the de facto ruler of Japan, exiling Nichiren to Sado Island under the supervision of Hōjō Nobutoki, the constable of Sado in 1261. However, this threatened exile did not stop Nichiren continuing his attacks on the other factions of Buddhism. The original plan was that Nichiren was to be escorted to Echi, to the residence of Homma Shigetsura, Hōjō Nobutoki’s deputy; from there he was to be taken directly to Sado Island. But Hei no Saemon, a government official and affirmed enemy of Nichiren decided to have him executed as he was being escorted to Homma’s residence. An attempt was made to behead Nichiren at Tatsunokuchi, but it was unsuccessful. Legend has it that as the executioner’s sword was about to come down on Nichiren’s neck, it broke in half. Various other supernatural happenings were alleged to have occurred to prevent and thwart his death. In this third print of the series Nichiren is seen in prayer, kneeling beside a pine tree which is growing close to the ocean. His executioner stands behind him. It depicts him about to be executed when the rays from the sun destroy the executioner’s sword, averting his death. Nichiren’s exile was later carried out as it had been originally planned.

The Star of Wisdom Descends on the Thirteenth Night of the Ninth Month

The fourth print of the portfolio is entitled The Star of Wisdom Descends on the Thirteenth Night of the Ninth Month and depicts Nichiren holding his rosary, standing before an old plum tree, in which appears a shining apparition of the Buddha. Behind him are two officials and a group of armed men. The scene is illuminated by the full moon which bathes the entire vista. Raymond A Bidwell the collector of oriental art and porcelain, wrote an article in 1930 for Artibus Asiae, a semi-annual publication of original scholarly articles, entitled Kuniyoshi III in which he likened Kuniyoshi’s depiction with that of Christian art:

“…the same spirituality and relationship of man to God as was expressed by the Italian primitives in their pictures of God appearing to the saints… Nichiren and the rough soldiers who have him in custody see in adoration and consternation a vision of The Buddha standing in the branches of a leafless plum tree on a clear moonlight night. The intense beauty of the evening sky and moon against the lace like branches of the aged and gnarled plum tree, make you feel that God must manifest himself directly…”

Bidwell’s conclusion was that Kuniyoshi transcended the Italian painters in his successful approach. Raymond A. Bidwell would later go on to donate the largest collection of Kuniyoshi prints in the U.S. to the Springfield Museum of Fine Arts.

…….to be continued.

Most of the information for this site came from various Wikipedia pages.