Ann Ingram (Nancy) Rayner

Samuel and Ann Rayner had nine children of which six excelled artistically like their parents. Having looked at the life of the parents in my previous blog I want to focus on the talents of their children.

Their first-born child was William but he died at childbirth and so the title of eldest child fell on to the shoulders of their daughter Ann Ingram Rayner who, to save confusion with her mother, was always known as Nancy. She was born in London in 1826 during the time when the family were living at 11 Blandford Street, Portman Square, Marylebone. A year after she was born, the family moved to Museum Parade in Matlock Baths, and her early years were spent in Derbyshire.

Nancy started her artistic studies at the age of ten and soon proved to be very talented. In her teenage years she was probably influenced by contemporaries of her father such George Cattermole, a fellow draughtsman working for John Britton. Another was Octavius Oakley, who had developed into a specialist of portraits in watercolour and was, like Samuel Rayner, given commissions by the Duke of Devonshire. Oakley tutored Nancy in the art of portraiture and Nancy’s ability at painting portraits was initially down to his work with her. Other luminaries who influenced Nancy were the Scottish painter, David Roberts who had been a long-standing friend of the Rayner family. When he returned from a sketching trip to Spain he gave Nancy one of his original pencil sketches. Samuel Prout, one of the masters of British watercolour architectural painting, was also a great inspiration to Nancy.

Nancy was the first of Samuel’s children to become an Associate of the Old Watercolour Society. The Society albeit supportive of watercolourists was a male-dominated society for it was only the male Associates who could progress to become full members of the Society and share in its profits and become administrators. Female associates were barred from this transitioning. At the time of Nancy’s election as an Associate there were only three other Associate female painters, Maria Harrison, Eliza Sharp and Mary Ann Criddle who were also affected by this ruling. They were well in the minority as there were 26 male members and 17 male associates. After sustained pressure from the ladies with regards this unfair treatment the Old Watercolour Society changed the rules and appointed them Honorary Lady Members. However, they still were not allowed to share in the profits of the Society.

Nancy then had her first painting exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1848, at the age of twenty-two, and was elected a Member of the Old Watercolour Society two years later. The sale of her paintings went well and she received many commissions and patronage. Princess Mary, Duchess of Gloucester was known to be one of Nancy’s patrons.

Her 1850 painting entitled Summer Pastimes, which is also known as Portrait of the Gloucester Children depicts two young children playing. It is thought that the children are in fact the Duchess’s children or maybe her grandchildren as if you look at the window on the right you can see a flag flying over a castle tower, signifying that is part of the royal estate.

Nancy Rayner’s life came to an early end in November 1855 at the age of twenty-nine and so her artistic life was cut short. As a talented painter, maybe if she had lived longer, she would have been as famous as her father or her famous sister, Louise.

Rhoda (Rose) Rayner

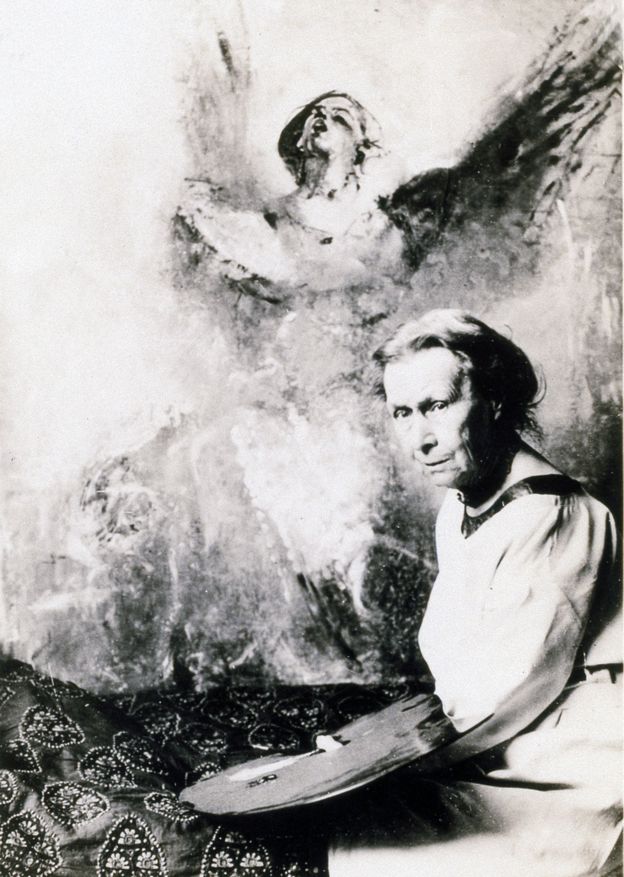

The second daughter of Samuel and Ann Rayner was Rhoda, known as Rose. She was born 1828 whilst her parents were living in the small Derbyshire town of Matlock Baths. Her artistic journey began as a teenager when she was taught how to create models using clay and she began to produce jugs and vases. Her late venture into the world of painting was probably due to her love of clay modelling and pottery and she would spend much time making and decorating her pottery figures. It was not until seven years later, around 1850, when she was twenty-one, that she began to paint with watercolours like her siblings. Four years later, in 1854, some of her paintings were seen at art exhibitions. One of the great artistic influences on Rose was the rise of the pre-Raphaelite painters.

Although her interests remained in watercolour painting and pottery her great love was teaching and it is thought that throughout her life she was involved in the private tuition of children whose parents could afford to give their children a good start in life. Rose was fortunate to be able to travel widely in Europe. The fact that she travelled so much and so far from home, like her trip to Russia in 1880 would mean that she had either become very prosperous or that she travelled as part of a wealthy family’s retinue.

Rhoda Rayner exhibited at the Royal Academy and elsewhere between 1854 and 1866, and it is thought it was during this period that she began to call herself Rose.

In the late 1870’s life changed for her. The marriage between her younger sister Frances and her husband Charles Coppinger in 1866 had come to an end. Frances left her husband and went with her daughter Annette (Netta) back to live at her parents’ home in New Windsor. It was in 1879 that Samuel Rayner died and it is thought that Rose’s share of his inheritance allowed her the independence to live on her own at 103 Dalberg Road in the London borough of Lambeth and following Frances’ return home Rose offered to look after Netta who was eleven years old.

In 1881 she completed a painting entitled Russian Balloon Seller, Streets of Petrograd. She had probably made preliminary sketches when she was visiting Russia in 1880 with her niece Netta and completed the work in her London studio.

Rose and Netta were still living together in 1891 according to the census of that year. Their home was now Hampstead in London and the census gives Rose’s occupation as Artist, Figure Painter, Sculptor and Annette’s occupation as piano music teacher.

In 1908, Rose’s younger brother Richard died, aged 65 and Rose moved to a new house and went to live next door to Richard’s family in Orpington Kent. Her niece Netta worked in a hospital during the First World War where she met a Canadian, Robert MacGregor, and when the war ended the couple were married and went to live in Canada. Rose died aged 92, in Orpington, Kent, on January 12th, 1921, just a few months after Netta and Robert sailed for Canada. Rose was the longest-lived of all her sisters.

Frances Rayner Copinger

Frances Rayner was the sixth child of Samuel and Ann Rayner. She was born in Piccadilly, London on August 19th, 1834 and along with her older brother Samuel and older sister Louise was christened at the Newman Street Apostolic Catholic Church in Marylebone the following February.

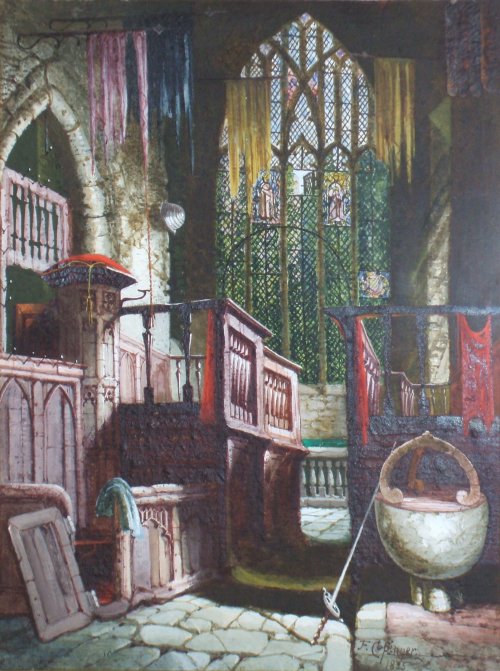

Frances’ artistic path differed to those of her elder siblings as she never exhibited any of her paintings until she was twenty-five years of age, and then only on one occasion in 1861 did she have a painting of hers, a watercolour, Church of St Andre, Antwerp, appear in a London gallery. It was exhibited in the Suffolk Street gallery in London. The one thing she had in common with her father was her love of architecture and especially the architecture of old religious buildings.

One of her great loves was travel and she journeyed throughout Europe on a number of occasions and from these travels was born a number of paintings featuring places in Europe. Frances Rayner married Charles Copinger in February 1867. It was Copinger’s second wife, his first wife Mary had died in 1866. From his first marriage Charles had five children and with Frances he had a daughter Annette Frances who was born on October 26th, 1867 and a son Ernest Edwin born in 1871. Following her marriage, Frances and her husband lived in Brussels for some years, but by the time of the census in 1871 she and the family had returned to England and were living in the London borough of Islington. The census reports her occupation as an artist and her husband’s occupation stated as being a clergyman of the Catholic Apostolic Church. There was one other occupant of their household, Copinger’s sister Clara, who acted as a governess for the children.

The marriage between Frances Rayner and Charles Copinger ended shortly after the birth of their son but there is no record of a divorce, which was very difficult to procure in those days. Notwithstanding that, Charles simply left Frances and went off to America and in Baltimore in 1878, with or without divorce, he married his third wife Mary Margaret May. They went on to have two daughters and a son. Charles Copinger died on May 9th, 1913.

After the breakdown of her marriage in the late 1870s, Frances left her husband and took the children to live with her mother and father but probably because of the problems of space in her family’s house, her daughter Annette went to live with Frances’ sister Rose. In the 1881 census Frances is noted as living with her son Ernest as a lodger in a house belonging to the Sevenoakes family in New Windsor on the outskirts of London.

Frances Rayner died in 1889, a year before the death of her mother, Ann. She was 55. At the time of his mother’s death, her son Ernest was about eighteen years of age. When Frances died Ernest went to live in Camberwell with his Aunt Grace who had married Frederick Catty in 1869 and the couple had five children of their own. Ernest became a merchant’s clerk when he was nineteen. He died in 1904

Of all the Rayner children the most talented was Louise and I will dedicate my final blog to her life and her beautiful works of art.

Besides the usual sources such as Wikipedia I got most of my information about the Rayner family from an excellent and comprehensive website entitled DudleyMall.

(http://www.dudleymall.co.uk/loclhist/rayner/samuel.htm)

It is really worthwhile you going to have a look at it.

I also gleaned information about Charles Copinger from the family blog :

http://www.copinger.org/page.php?file=1_34

One of her favourites was one she did of her three children.

One of her favourites was one she did of her three children.

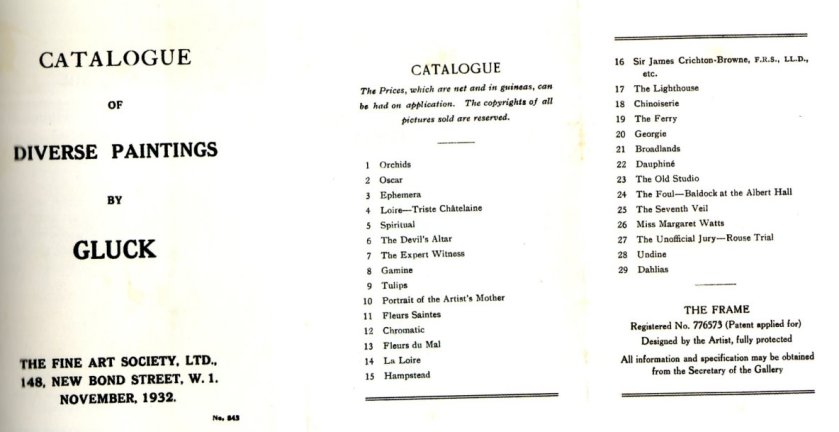

Most of the information for this blog came from two excellent books – Gluck: Her biography by Diana Souhami.

Most of the information for this blog came from two excellent books – Gluck: Her biography by Diana Souhami. Gluck Art and Identity by Amy De La Haye (Author), Martin Pel (Author), Gill Clarke (Author), Jeffrey Horsley (Author), Andrew Macintos Patrick (Author)

Gluck Art and Identity by Amy De La Haye (Author), Martin Pel (Author), Gill Clarke (Author), Jeffrey Horsley (Author), Andrew Macintos Patrick (Author)

This close relationship with Nesta was to lead to Gluck’s most famous painting, completed in 1936, known as Medallion or the YouWe painting. The work is a portrait of Gluck and Nesta Obermer and according to Gluck it came about after the two women went to see the Mozart opera, Don Giovanni at Glynbourne on June 23rd 1936. Nesta and Gluck sat in the third row of the stalls and Gluck recalled how she felt the intensity of the music which fused them into one person and matched their love. In her biography of Gluck, Diana Souhami describes the painting:

This close relationship with Nesta was to lead to Gluck’s most famous painting, completed in 1936, known as Medallion or the YouWe painting. The work is a portrait of Gluck and Nesta Obermer and according to Gluck it came about after the two women went to see the Mozart opera, Don Giovanni at Glynbourne on June 23rd 1936. Nesta and Gluck sat in the third row of the stalls and Gluck recalled how she felt the intensity of the music which fused them into one person and matched their love. In her biography of Gluck, Diana Souhami describes the painting:

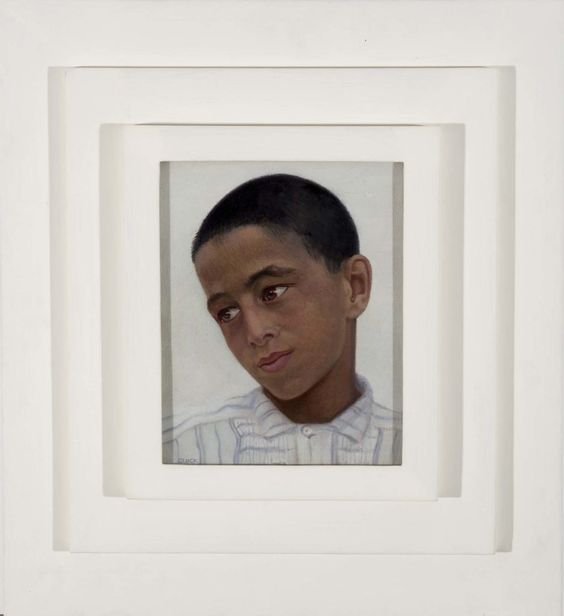

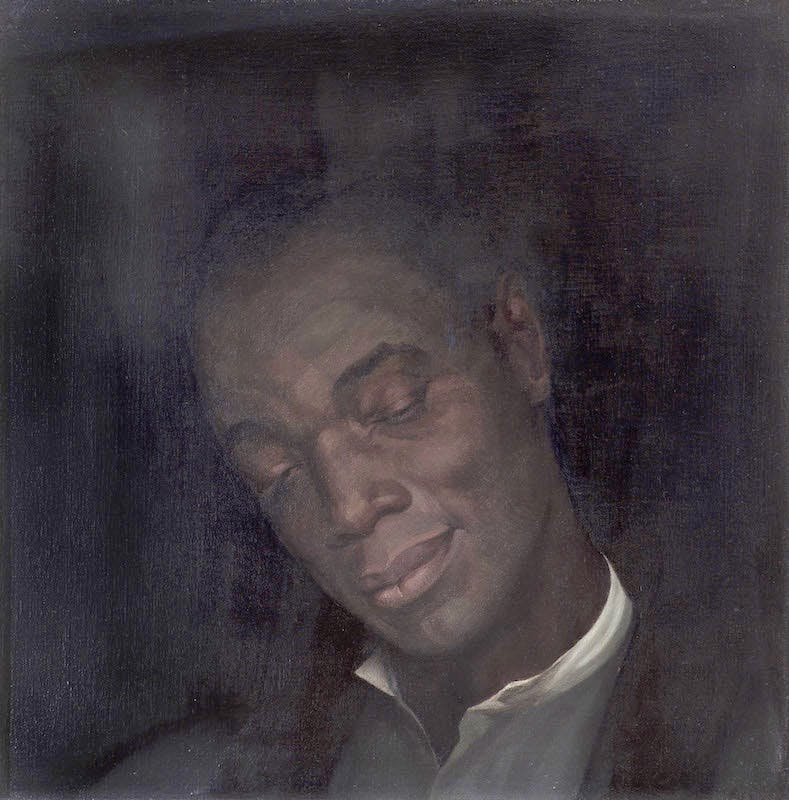

One of her pictures from those North African stays is a depiction of the head of a young Arab boy. She said that she was madly excited by the beauty and subtlety of the skin of the boy. She commented:

One of her pictures from those North African stays is a depiction of the head of a young Arab boy. She said that she was madly excited by the beauty and subtlety of the skin of the boy. She commented:

Most of the information for this blog came from the excellent book – Gluck: Her biography by Diana Souhami.

Most of the information for this blog came from the excellent book – Gluck: Her biography by Diana Souhami.

Most of the information for this blog came from the excellent book – Gluck: Her biography by Diana Souhami.

Most of the information for this blog came from the excellent book – Gluck: Her biography by Diana Souhami.