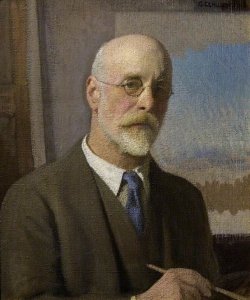

In my next two blogs I am going to look at the lives and works of two English painters, the father, Thomas Benjamin Kennington and his son, Eric. Today I am going to concentrate and examine some of the works of the father and tomorrow, switch to look at the art of his son.

Often when we watch a tear-jerker type film or read a heartbreaking fictional novel, we tend to be critical of the sugary-sweet, heart-tugging subject. My featured artist today produced many paintings which, although of the realism genre, also wanted us to be emotionally moved by what we saw before us. His paintings were often studies of the problems which beset the poor in Victorian England. Today let me introduce you to the Victorian social realism painter and master of portraiture, Thomas Benjamin Kennington.

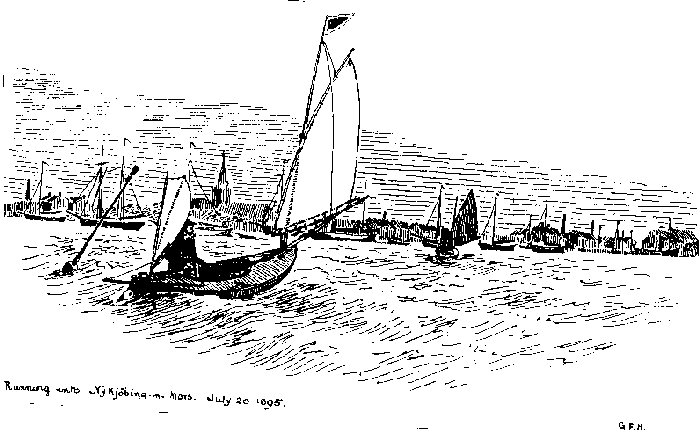

Kennington was born in the Lincolnshire fishing port of Grimsby in April 1856. As a young man he studied painting at the Liverpool School of Art, where he won a gold medal, and the Royal College of Art in London. He also went to Paris where he enrolled at the Académie Julian and studied under William-Adolphe Bougereau and Tony Robert-Fleury. Thomas Kennington lived at a time when there were a large number of families living on the “bread line”; a term used denoting the poorest condition in which it is acceptable to live, with some even dying of starvation on the city streets. The population of Great Britain increased three-fold during the nineteenth century due to many factors, such as an influx of people from Ireland who were escaping the potato famine, life expectancy had increased and infant mortality had decreased. Jobs were hard to find in the countryside so folks had flocked to the urbanized areas seeking work. With such a pool of workers, owners and businessmen could pay low wages, often so low that workers could not afford to feed or house their families. In the middle of the nineteenth century it was estimated that there were more than thirty thousand homeless children living on the streets of London. However, many of the well-off folk were less than sympathetic with regards their plight and believed that any money given to the poor was simply squandered on drink and gambling and did not, in any way, solve the underlying social problems at all.

Thomas Kennington was a social activist who was disturbed by the poverty he saw around him and decided that, through his art, he would highlight the plight of the poor. The first painting I am showcasing is entitled Homeless which he completed in 1890, whilst living in London. In 1892 it was sent to Melbourne for the large Anglo-German exhibition which was held in Melbourne’s exhibition centre and the painting is now housed in the Bendigo Art Gallery in Australia.

The setting for the work is unknown but presumed to be London. In the background, partly hidden by the smog, we see a gas works and a tall chimney belching out smoke. This is a scene of urban pollution; a gloomy streetscape. In the foreground we see a woman dressed in widow’s garb supporting a young boy’s body, partly lifting him up from the wet pavement. The young lad’s face is white and his head has lolled to the side. He looks to be in a bad way, possibly close to death. His eyes vacantly stare out but he seems unaware of his surroundings. The artist has further depicted the depressing state of affairs by limiting the depiction of nature to a lifeless-looking tree at the right of the painting. It is leaf-less with one of its lower branches broken off and the whole of it is encased in the concrete pavings which will inhibit its growth.

Critics praised Kennington’s painting when it was first exhibited. The art critic of the Melbourne Argus described the work:

“…full of pathos … both a poem and a sermon…”

while another Melbourne newspaper, The Age, told its readers to study the face of the child and described the work as:

“…a chef d’œuvre of artistic power and human sympathy … a face … that expresses all the patient suffering of a whole class, amongst whom the inheritance of sorrow and privation is patiently accepted and endured…”

Another work of art which focused on how poverty can affect families was summed up in Kennington’s work entitled Widowed and Fatherless, 1888. In this depiction we have a mother whose husband has died and she is left with the monumental task of rearing her children. One child is lying on the bed. Maybe she is asleep or maybe she is very ill. Her sister kneels at the bedside praying, maybe praying that her sister will recover from her illness. The mother sits in a chair stitching clothes but she cannot take her eyes off her sick daughter.

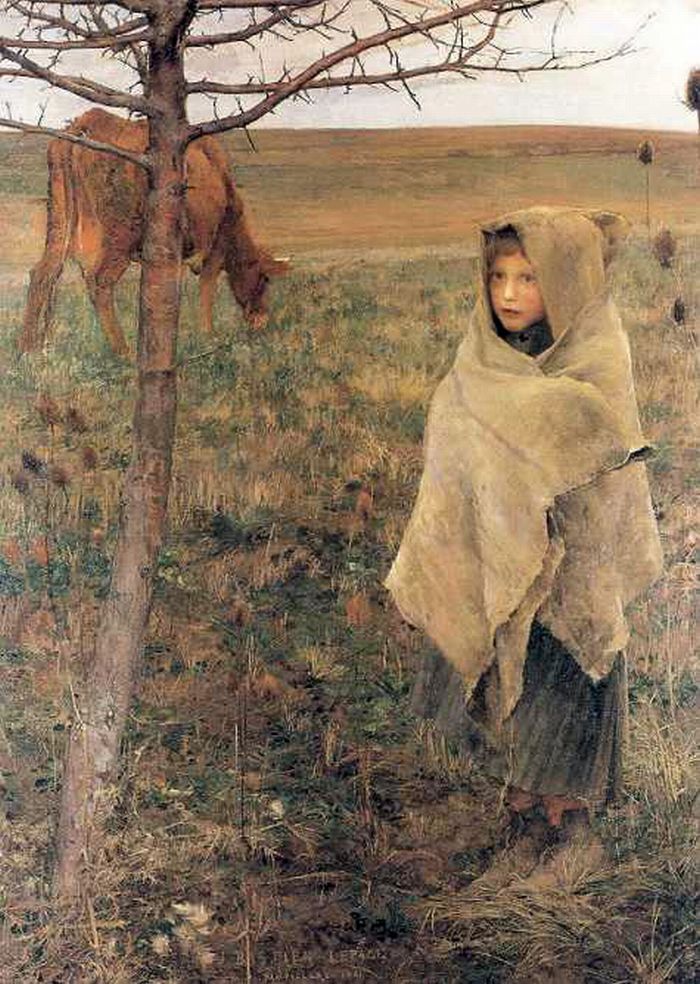

A very moving painting depicting the plight of the poor is one Kennington completed in 1885 entitled Orphans. There is a similarity in this depiction of poverty with the 1650 work by the great Spanish painter, Bartolomé Esteban Murillo in his work The Beggar Boy. (See My Daily Art Display January 25th 2011). Before us we see two young boys. They could be brothers. Their clothes are no more than rags. The older boy’s head is slumped to the side due to his tiredness. He can hardly keep his eyes open but they stare down at the head of the younger boy who through circumstances beyond his control, is whom he has to look after. The younger boy, with his rosy red cheeks, sits on the floor and leans against the older boy for comfort, his head and arm rest on the older boy’s thigh. He stares out at us in a beseeching way. What is he asking us? Is it merely sustenance or does he want our love and our protection from the deprivation he is forced to suffer. On the floor before the two boys is a plate with a piece of dried bread highlighting their plight. This is a prime example of Kennington’s depictions of the urban poor. The painting was purchased by Henry Tate, the sugar merchant and philanthropist, who established the Tate Gallery in London.

A crust of bread appears in another painting by Kennington, entitled Daily Bread which he completed in 1883. The title probably derives from the words of the Lord’s Prayer, give us our daily bread. This is a very emotional depiction of poverty and it was hoped that by depicting such dprivation things would change. Alas, it was not to happen for many years and even now child poverty and child beggars exist in Great Britain.

In contrast to the abandoned children we saw depicted in the previous paintings, the next painting, simply entitled The Mother, was Kennington’s idea of what family life should be about and how children should be brought up in a safe and loving environment. This large work (115 x 168cms), which was completed in 1895, depicts a moment in family life when a mother says goodnight to her children.

This is a form of narrative painting as from about the seventeenth century, genre painting showed scenes and narratives of everyday life. Later, during the Victorian age, narrative painting of everyday life subjects became very popular and such art was often considered as a category in itself termed Victorian Narrative painting. This theme of what family life should be about was a recurrent theme in Victorian art. Domesticity was the order of the day focusing on how children and adults should behave within a family environment. It was hoped that families could learn by what they saw through the medium of visual art. This huge painting of The Mother by Kennington depicts her as the foundation stone of the family, the person who underpins the family group. The painting also alludes to another idea regarding Victorian family group. If you look carefully at the dead centre of the work you will see the wedding ring on the mother’s finger and this could be the way in which the artist want to share his belief that marriage was also very important part of the family structure and family values.

In this painting we see the mother tending two of her young children. Although the mother is the focal point of the painting she is depicted with her back to us. We do not see her face clearly. She is being helped by an older daughter, who is learning about the role of motherhood. The lighting of the painting is interesting. The darker silhouette of the mother is in contrast with the brighter area around the two sleeping children, which is lit up by the light emanating from the lamp held by the mother and which is hidden from our view. Of course this view of the family is a romanticised view of life in Victorian days and maybe it was more to do with what Kennington believed family life should be rather than the actuality. This painting belongs to the Aigantighe’s Gallery in Hobart, Tasmania

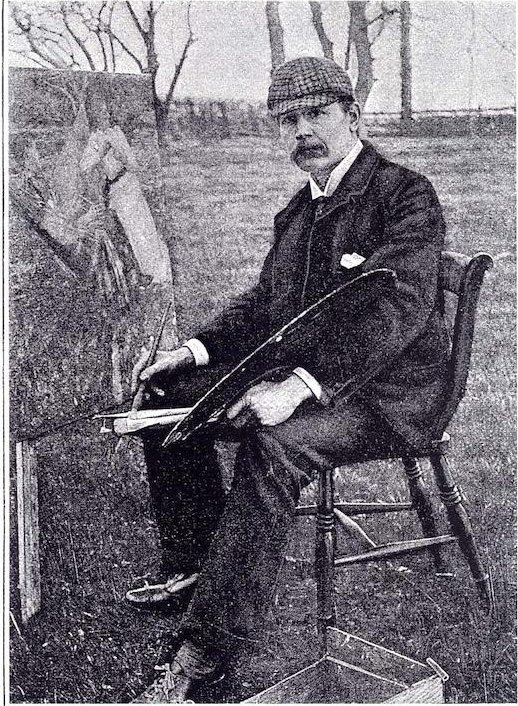

Thomas Kennington exhibited his works in the Royal Academy of Arts every year from 1880 until his death in 1916. His paintings were also regularly on show at the Royal Society of British Artists (RBA) and the popular Grosvenor gallery in London. Kennington was a founding member and became the first secretary of the New English Art Club which was founded in 1885 and was one of the founders of the Imperial League of Art in 1909. This society was set up to protect and promote the interests of Artists and to inform, advise and assist Artists, who have enrolled as members, in matters of business connected with the practice of the Arts Its role was to aid the artists and the protection of their interests. Kennington exhibited internationally in Paris and Rome and so good was his work that he was chosen to exhibit at the Universal Expositions held in Paris in 1889, where he was awarded a bronze medal.

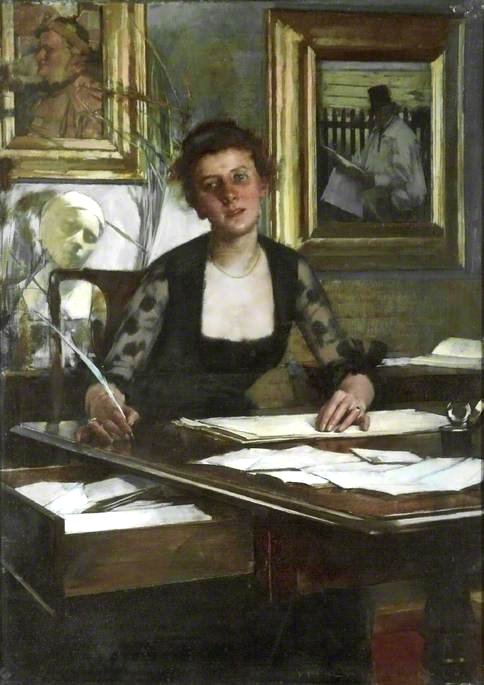

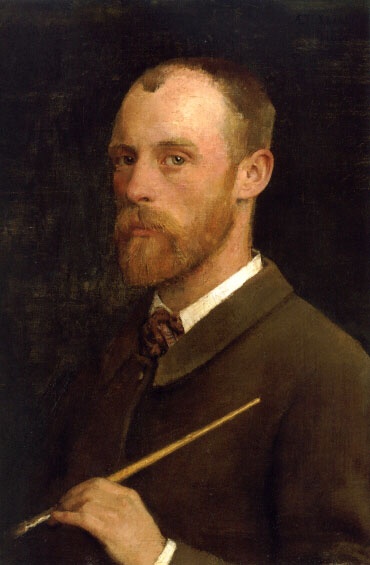

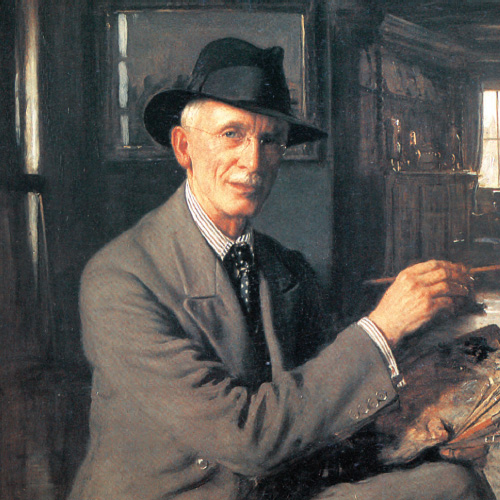

Besides his genre pieces which highlighted Victorian poverty, Kennington was an accomplished portraitist. Many of his portraits featured family members. In 1883, aged twenty-seven, Thomas Benjamin Kennington married twenty-two year old Swedish beauty, Elise Stevani, who was born in Lund a town in Southern Sweden 1861.

His daughter Ann also featured in a couple of his works. One was with her as Alice in Wonderland.

The other, when she was older, was of her, dressed as a Russian lady holding a balalaika.

My last offering is another interesting work by Kennington which he completed in 1882 and entitled The Ace of Hearts. There is an element of trickery about this depiction. We see the lady seated before us staring directly at us But are we who she is looking at? Look carefully at the mirror on the wall, above and behind her.

The image in the mirror indicated that the lady is looking straight through us, and focusing upon a man who can be seen scratching his neck. He seems perplexed by what the woman is doing with the cards. Look at the expression on the lady’s face. It is one of satisfied triumph as she points to the ace of hearts and we can thus deduce that she was performing a card trick for the gentleman. He is amazed and she is exultant with her trickery.

Thomas Benjamin Kennington died in London in December 1916 aged 60. His wife Elise died at the young age of 34 in 1895. Their son Eric was to go on to be a famous artist and in my next blog I will look at some of his work.