In my last blog I looked at the early life of Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson and featured some of his paintings which depicted the horrors of the First World War. Today I want to conclude his life story and look at some of his other works of art which had nothing to do with war but which I find have their own beauty.

Nevinson had been taken ill in 1912 and was moved to Buxton to convalesce and it was whilst partaking of the healing waters at the Hydro that he met Kathleen Knowlman who had accompanied her father to the health resort. With the outbreak of war in 1914, Nevinson, being a conscientious objector, had joined the Royal Army Medical Corps in November 1915. It was in this capacity that he had helped tend the wounded who had been brought home from the Front. He was stationed at the Third General Hospital in London but was always aware that soon he would be called to leave the relative safety of England and travel to France. Fully realising his possible death at the Front he decided that he should be married before he met his fate ! On November 1st 1915 he married Kathleen Knowlman. It turned out that he was never sent to the front as he was invalided out of the army following bouts of pericarditis and rheumatic fever which he contracted in January 1916 which left him crippled and for a time he began to think he would never walk again. He recalled the time in his 1935 autobiography, Paint and Prejudice:

“…I was now crippled completely. I began to think I should never walk again. Everything was tried on me while I lay helpless on my bed…”

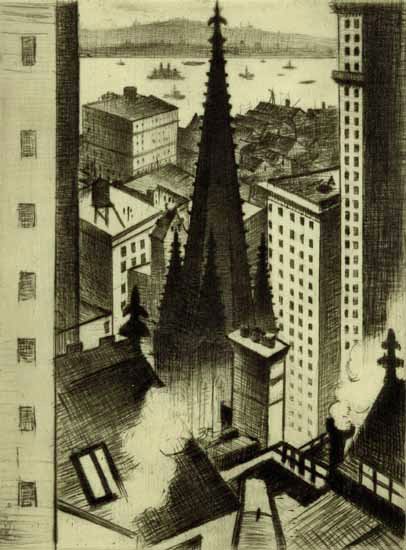

Drypoint. Trinity Church facade from the back, which faces Wall Street

With the ending of the First World War in 1918, the public’s desire for his war paintings and their harrowing depictions of the suffering of the troops waned. Maybe people just wanted to forget about the previous four years and did not want to be reminded of the brutality of war. For Nevinson, his favoured and once much appreciated subject matter had dried up and he had to make a decision as what to do next. Paul Nash, a contemporary of Nevinson and also a war artist, summed up the war artists’ dilemma when he talked about the ‘struggles of a war artist without a war’. At the end of the war, Nevinson went to Paris looking for new inspiration but soon tired of the French capital, a place he had visited as a child with his mother. In the spring of 1919, he decided to visit America and in particular New York. He had received an invitation from David Keppel to visit the American city to stage an exhibition of his War prints. David Keppel who with his father, Frederick Keppel, were print publishers and owned a four-storey gallery on 4 East 39th Street in Manhattan. They had exhibited many of Nevinson’s war prints which proved very popular with the American public.

Nevinson was made very welcome on his arrival and according to David Boyd Haycock in his 2009 book about the artist, A Crisis of Brilliance, relates how Nevinson was welcomed as a ‘war hero and victimised genius of modern European art, come to discover the USA and reveal it to itself ‘ Nevinson, on his arrival in New York, was taken aback by the city’s architecture, so much so when questioned by a local journalist of how he liked the city he commented that he loved the buildings so much he believed the city had been built for him. Nevinson would roam around the city constantly sketching and after a month long stay in America, he returned to London and converted his sketches into paintings. On his return to London he was to receive sad family news. Whilst he was in America his wife had given birth to a son, Anthony Christopher Wynne on 21st May 1919. His mother, Margaret, recorded that the child only lived for fifteen days, which, as she put it, had been “just enough time to get fond of him.” Nevinson later wrote in his autobiography:

“…On my arrival in London I was met by my mother, who told me my son was dead…”

And he later added in a somewhat morbid fashion:

“…I am glad I have not been responsible for bringing any human life into this world…”

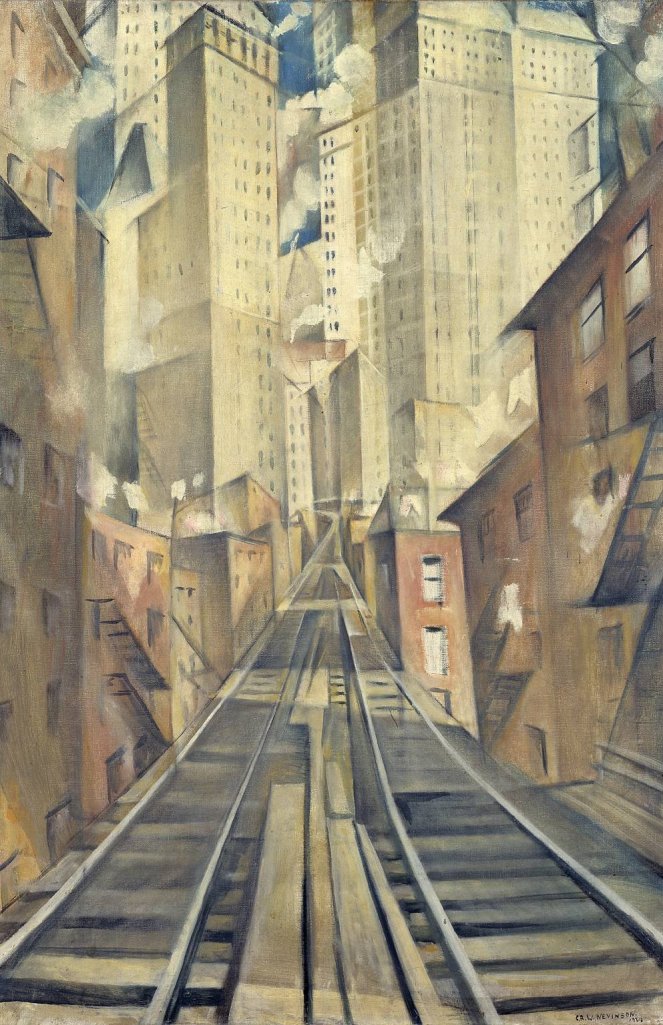

One of Nevinson’s depictions of New York, which he completed back in London in 1920 before he returned to America that October to set up his second exhibition of work at Frederick Keppel & Co, New York gallery, was entitled The Soul of the Soulless City (‘New York – an Abstraction’). The painting depicts an idealised view of a section of the elevated railway which ran through Manhattan. It was an unusual work with a narrow chromatic range reliant mainly on shades of greys and browns with just merest hint of blue for the skies between the tops of the skyscrapers. The way he has depicted the skyscrapers with their complex faceting harks back to Picasso and Braque’s cubism of a decade earlier. There is something very powerful and impressive about the way Nevinson has depicted the railway line receding dramatically into a cluster skyscraper blocks. There is a sense of speed about the disappearing railway track. Nevinson, was associated with Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and his concept of futurism, who wanted to revolutionize culture including art and make it more modern. The new ideology of Futurism was an art form which stressed modernity, and the virtues of technology, machinery, and speed and we can see in this work that Nevinson was a great believer of the ideals of futurism.

When the work was first exhibited at the Bourgeois Galleries in New York it was entitled New York – an Abstraction. It was not received well. According to David Cohen in his 1999 The Rising City Urban Themes in the Art and Writings of C.R.W.Nevinson’, C.R.W.Nevinson The Twentieth Century, one critic went as far as to dub the painting “inhuman, metallic and hard”. Later when he exhibited the work in London in 1925 at the Faculty of Arts Exhibition, Grosvenor House, London, it was given the title of The Soul of the Soulless City and this change was almost certainly made by Nevinson himself and although it has been likened to Karl Marx’s comment on religion being the “heart of the heartless world”, it could also be because Nevinson had fallen out of love with the American city.

Another work by Nevinson with New York as its subject is New York, Night which he completed somewhere between 1919 and 1920. This work which was completed around the same time as the previous work and was painted at the time when Nevinson was still in love with New York. There can be no doubt about his initial love affair with New York for Nevinson was quoted by David Cohen in his 1999 book, C.R.W. Nevinson, The Twentieth Century:

“…New York, being the Venice of this epoch, has triumphed, thanks to its engineers and architects, as successfully as the Venetians did in their time..Where the Venetian drove stakes into his sandbanks to overcome nature, the American has pegged his city to the sky. No sight can be more exhilarating and beautiful than this triumph of man…”

The painting depicts the busy harbour of New York at night. It is a view I have witnessed many times from the bridge of a ship as the city’s skyscrapers loom large ahead as we enter the port. In the painting we see the giant buildings through the smoke and steam emanating from the funnels of the small tugs and ferries which ply their way up and down the Hudson River. It is a mystical and atmospheric scene. It is a scene depicting industry. This is a scene of modernity, loved by the futurists. In the foreground we see jibs of cranes busily working on the loading and unloading of cargo vessels berthed at Brooklyn, across the river from Manhattan.

Nevinson built up a collection of prints of Manhattan, another of which is the drypoint print entitled Looking through Brooklyn Bridge. This work and another entitled Under Brooklyn Bridge are housed in the British Museum and were part of a set of ten drypoints of the city of New York which were commissioned by Frederick Keppel. Whenever I visit New York I always take time to walk across this bridge and never fail to be enthralled by the views on offer when crossing from Brooklyn to Manhattan. What first strikes you about this work is how the bridge is the central “character” as it dwarfs the people we see walking across it. In the background, through the mist, we see the colossal skyscrapers of Manhattan looming before us. In the evening light they lack colour and are just presented as grey giants. It is a cold depiction. There is no warmth about it. It is an inhospitable scene and the mist which gives a haziness to the skyscrapers also gives a feeling that the air may also be polluted. The people are wrapped up in warm clothes and the wooden walk way looks wet as if the rain has been beating down on the massive structure. The man in the foreground holds an umbrella but probably due to the strong winds, dare not open it to protect himself. Nevinson has managed to convey the massive structure as a monument to the permanence of the new Industrial time and it contrasts with the temporary nature of the people, who appear on it as mere shadows as they hurry from one side to the other.

Like a lot of artists, Nevinson did not take criticism and rejection well and his love for New York and America disappeared. Not only were his paintings attracting criticism, he himself was also becoming disliked for his ill-conceived outbursts. He often suffered periods of depression and would often be volatile. He had an unfortunate habit of bragging and publicly aired embellished claims of his war experiences, which people found hard to accept and together with his depressive and temperamental personality, he became an unpopular figure on the New York art scene. Whether it was because of the poor reviews or his growing dislike for the people around him, he decided to leave America.

So who was to blame for Nevinson’s falling out of love with America and the Americans. Maybe the answer lies in the 1920 catalogue introduction to an exhibition of Nevinson’s work by the art critic Lewis Hind. Of Nevinson he wrote:

“…It is something, at the age of thirty one, to be among the most discussed, most successful, most promising, most admired and most hated British artists…”

In Julian Freeman’s biography on Nevinson he talked about the artist’s mental state during the last couple of decades of his life:

“…From 1920 until 1940 they carried his strident, maverick diatribes, aimed at society at large, and at the establishment in all its forms… and the variety, salacity, and often uncompromising savagery of his egocentric articles remains enormously entertaining. However, his autobiography is marked and marred by a strong undercurrent of confrontational right-wing xenophobia, and some of his private correspondence in the Imperial War Museum in London is explicitly racist: true signs of the times to which he was such a conspicuous contributor…”

I will leave the last word to the artist himself who, in his 1937 autobiography, Paint and Prejudice, wrote:

“…My prices have always been humble, but it has been possible up to the present to lead the life of a millionaire. Far from being a starving artist, a great deal of my time has been taken up in refusing food and drink, affairs with exquisite women, and wonderful offers of travel or hospitality. But I have always been driven mad by the itch to paint. Painting has caused me unspeakable sorrows and humiliations, and I frankly loathe the professional side of my life. I am indifferent to fame, as it only causes envy or downright insult. I know the necessity of publicity in order to sell pictures, because the public would never hear of you or know what you were doing unless you told them of it. But publicity is a dangerous weapon, double-edged, often causing unnecessary hostility and capable of putting you into the most undignified positions. Until of late I have had to fight an entirely lone hand. When I exhibited at the Royal Academy it was a revelation to me how well the publicity was done through the dignity of an institution rather than through the wits of an individual. But I suppose that now I shall always remain the lone wolf. I have been misrepresented so much by those who write on art that the pack will never accept me. Incidentally, because I painted I have earned something like thirty thousand pounds for the critics, curators, or parasites of art. Ninety per cent of their writings has consisted of telling the public not to buy my pictures and of charging me with every form of charlatanism, incompetency, ignorance, madness, degeneracy, and decadence. It is useless to deny that this has had its effect..”

His post-war career was not so distinguished. He never achieved the adulation that was bestowed on him due to his war paintings. Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson died in October 1946 aged 57.