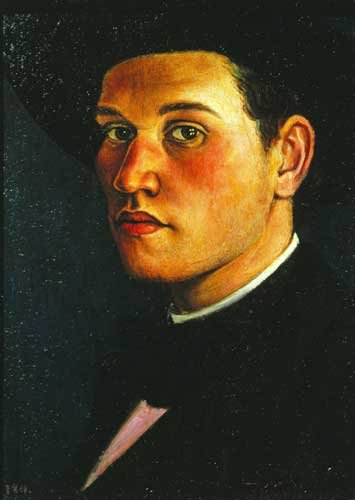

by C.R.W Nevinson

The newspapers and television are awash with articles and documentaries with regards the First World War and so, over the next two blogs, I thought I would take this opportunity to look at one of the best known British war artist, many of whose paintings featured the Great War. His name is Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson, but is often referred to as C.R.W. Nevinson, and was known to his friends as Richard.

Nevinson was the son of Henry Nevinson, who was a British war correspondent during the Second Boer War and the First World War. His father was a fierce and radical campaigning journalist who, through the might of his pen, fought to end slavery in Western Africa. He was also a suffragist, and along with the left-wing writers, Henry Brailsford, Max Eastman and Lawrence Housman founded the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage society in 1907. In 1884 he had married Margaret Nevinson an activist in the campaign for women’s rights and in Hampstead, London in August 1889 she gave birth to their only child, Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson. An insight into his early childhood can be gleaned from a book written by Frank Rutter in 1935 entitled Art in my time and in it he talks about Nevinson and his parents. He wrote:

“…Nevinson was the child of parents who had singularly noble ideas, who were markedly progressive and humane in their habit of thought… Nevinson started life with a pre-natal tendency to revolt against injustice, cruelty and oppression…”

He also commented on how tied up Nevinson’s parents were in their campaigning and quotes young Nevinson as being somewhat critical of his mother’s lack of time for him. Later, Nevinson wrote of his mother:

“…If my mother does happen to be in for a meal she is so engrossed in other things that she hardly hears and certainly never takes in a word I say.”

Nevinson’s parents were so wrapped up in their own agendas it was bound to affect the early life of their son and for young Nevinson, who after a period in kindergarten, at the age of seven, worse was to come as his parents decided to send him away from home to a boarding school. For a child who just wanted his parents to spend time with him it was the worst possible outcome and he hated the school and was soon in trouble. In his 1935 autobiography, Paint and Prejudice, he wrote about his time as a boarder:

“…In due time I went to a large school, a ghastly place from which I was rapidly removed as I had some sort of breakdown owing to being publicly flogged, at the age of seven, for giving away some stamps which I believed to be my own. I was not only described as a thief but as a fence. From this moment I developed a shyness which later on became almost a disease. During my sufferings under injustice a conflict was born in me, and my secret life began…”

If school life was bad enough, life at home did not improve. His father’s strong pro-Boer utterances during the Second Boer War became well known and disliked and his son was tarred by this same brush of loathing and would be treated like an outcast by his young contemporaries.

In 1903, Nevinson was sent to Uppingham School. The school was strong in its teaching of engineering and art. However he described the time at Uppingham as a débâcle. At first the school seemed acceptable to the fourteen year old but things deteriorated for the teenager as probably due to his earlier school experiences he did not make friends easily and was singled out by both staff and fellow pupils and he wrote of his horrific experiences at the hands of older students:

“…”I had no wish to go to any such school at all, but nevertheless Uppingham did seem to be the best. Since then I have often wondered what the worst was like. No qualms of mine gave me an inkling of the horrors I was to undergo. Bad feeding, adolescence – always a dangerous period for the male – and the brutality and bestiality in the dormitories, made life a hell on earth. An apathy settled on me. I withered. I learned nothing. I did nothing. I was kicked, hounded, canned, flogged, hairbrushed, morning, noon and night. The more I suffered the less I cared…”

Normality finally came into his life when he left Uppingham School and enrolled at St John’s Wood School of Art where he would train to pass the exams required for entry to the Royal Academy Schools. Nevinson summed up this move in his autobiography in a simple sentence:

“…From Uppingham I went straight to heaven…”

Life at the art school was so different in comparison to his previous schools and Nevinson began to come out of his shell and this could well have been helped by the fact that he was now in the company of female students. He recalled the happy days of socialising with the girls and acknowledged that he himself was changing:

“…My shyness went, and I spent a good deal of my time with Philippa Preston, a lovely creature who was later to marry Maurice Elvey. There were others, blondes and brunettes. There were wild dances, student rags as they were called… and various excursions with exquisite students, young girls and earnest boys; shouting too much, laughing too often…”

However it was not the Royal Academy Schools for Nevinson as he had been influenced by the works of Augustus John who, along with his sister, Gwen, had been students at the Slade School and so, in 1909, aged twenty, Nevinson entered the Slade School. Most of his friends from St John’s Wood School of Art progressed on to the Royal Academy School and so Nevinson arrived at the Slade knowing nobody. After an initial nervousness and an uncertainty about his choice of artistic direction he settled in and made a number of friends. In his class were aspiring artists such as Mark Gertler, Adrian Allinson, Edward Wadsworth, Rudolf Ihlee and Stanley Spencer. This group of young artistic friends were known as the Coster Gang because they dressed in black jerseys with scarlet mufflers and atop their heads they would wear a black cap or hat similar to those worn by costermongers, the street sellers of fruit and vegetables.

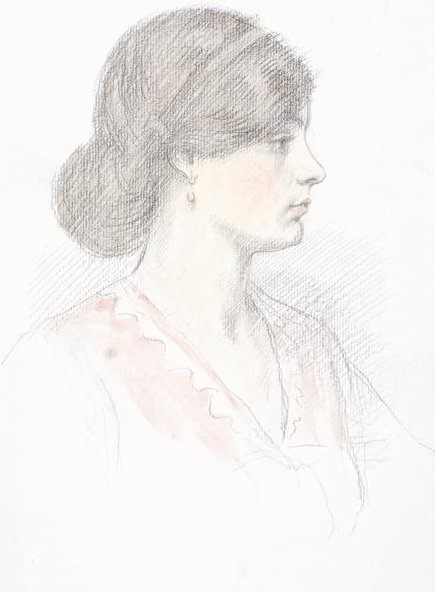

In 1910 a new student joined the Slade. She was Dora Carrington. In Michael Walsh’s 2002 biography on Nevinson which looked at his energetic early career he wrote of Nevinson and Carrington’s relationship:

In 1910 a new student joined the Slade. She was Dora Carrington. In Michael Walsh’s 2002 biography on Nevinson which looked at his energetic early career he wrote of Nevinson and Carrington’s relationship:

“…Nevinson’s infatuation with Dora Carrington became progressively more acute. In Carrington he had met his match, not only in intellect and in personality, but also in that she could be as obtuse as he could… The friendship was always confused, faltering between brotherly affection and unfulfilled love affair, rooted in Nevinson’s reluctance to trust strangers and her notorious desire to remain unattached…”

With this fascination with Dora came a major problem. Dora had another great admirer and he was Nevinson’s best friend, Mark Gertler. Gertler and Nevinson had spent much time together after classes and a bond between them ensued. Michael Walsh in his 2002 biography of Nevinson, C. R. W. Nevinson: The Cult of Violence, wrote about this close friendship:

“…Together they studied at the British Museum, met in the Café Royal, dined at the Nevinson household, went on short holidays and discussed art at length. Independently of each other too, they wrote of the value of their friendship and of the mutual respect they held for each other as artists…”

However they had both fallen in love with Dora Carrington and in a way she destroyed the friendship between the two men. Nevinson after some tentative efforts to move his relationship from a close platonic one to something more was spurned by Carrington and she began to distance herself from him. Nevinson was devastated at this turn of events and wrote to her:

“…I am now without a friend in the whole world except you…. I cannot give you up, you have put a reason into my life and I am through you slowly winning back my self-respect. I did feel so useless so futile before I devoted my life to you.”

Nevinson also realised that his attempt to become Carrington’s lover ended his friendship with Gertler. Gertler was in love with Carrington and now Nevinson, once his closest friend, had now become a rival for Carrington’s affections. Something had to give and Gertler wrote to Nevinson:

“…I am writing here to tell you that our friendship must end from now, my sole reason being that I am in love with Carrington and I have reason to believe that you are so too. Therefore, much as I have tried to overlook it, I have come to the conclusion that rivals, and rivals in love, cannot be friends. You must know that ever since you brought Carrington to my studio my love for her has been steadily increasing. You might also remember that many times, when you asked me down to dinner. I refused to come. Jealously was the cause of it. Whenever you told me that you had been kissing her, you could have knocked me down with a feather, so faint was I. Whenever you saw me depressed of late, when we were all out together, it wasn’t boredom as I pretended but love…”

The romantic hopes of both Nevinson and Gertler were spurned by Carrington and the two men paid an enormous price because of their infatuation with their fellow student. The price was the ending of their own close and once fulfilling friendship.

Nevinson left the Slade School in the summer of 1912 and travelled to Paris, a place he had visited on a number of occasions with his mother. It was in the French capital that he met and became friends with Gino Severiniand Filippo Marinetti, an Italian poet and editor, the founder of the Futurist movement. Futurism was originally an Italian movement which was characterised by its belligerent celebration of modern technology and city life and energetically showed contempt for Western Art traditions. Nevinson was excited with these futurist ideas and he and Marinetti co-wrote the English Futurist manifesto Vital English Art, in June 1914 edition of English newspaper, The Observer.

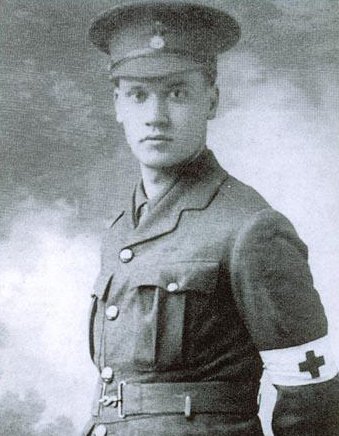

On the outbreak of the First World War, Nevinson, who was a fervent pacifist, refused to become involved in combat duties, and volunteered instead to work for the Red Cross. Nevinson joined the Friends Ambulance Unit, which was a voluntary ambulance service founded by some young members of the Quakers. It was independent of the Quakers’ organisation and mainly run by registered conscientious objectors. Later, between November 1914 and January 2015, Nevinson served as a volunteer ambulance driver. However his time in the ambulance service as driver, stretcher bearer and hospital orderly ended in January 1915 when he had to return to home due to ill health.

The brutality of the war stimulated him and on his return home in January 1915 he wrote an article for the Daily Express about this artistic stimulation:

“…All artists should go to the front to strengthen their art by a worship of physical and moral courage and a fearless desire of adventure, risk and daring and free themselves from the canker of professors, archaeologists, cicerones, antiquaries and beauty worshippers…”

I will leave Nevinson’s life story at this juncture and return to it in my next blog. I now want to feature three of his war paintings which were to make him famous and which depicted life and the brutality of the First World War. It was during his period convalescing that he started on a series of works based on his own experiences and incidents he witnessed whilst at the Western Front in France.

by C.R.W. Nevinson (1915)

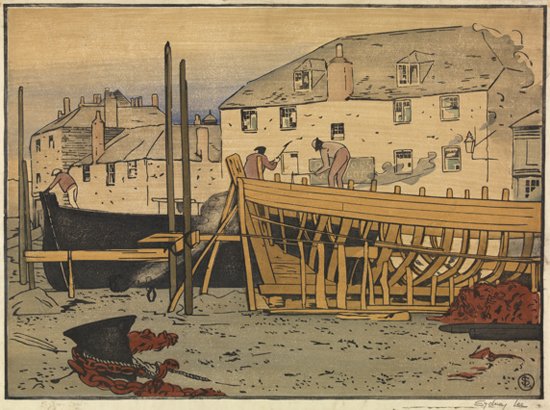

One such work was entitled La Mitrailleuse (The machine gun), which he completed in 1915. The work is a depiction of a French machine-gunner and two of his comrades in a battle trench. It is amazing how Nevinson has portrayed the soldiers simply as a series of angular planes and has kept the colours to various tones of grey. There is something mechanical about the men. He has de-humanized them. The angularity of their facial expressions and the dark colouring around their eyes transforms them into fierce-looking individuals who seem to lack any trace of humanity. The machine gun, which is the title of the painting, is gripped by the gunner. The belt of bullets hangs from the machine ready to be spat out and mercilessly cut down the enemy. Of the painting Walter Sickert, the Camden Town Group painter described the painting as:

“…the most authoritative and concentrated utterance on the war in the history of painting…”

The second painting I am featuring is entitled Harvest of Battle, which can be found at the Imperial War Museum, London. In this work we observe the deadly aftermath of battle. The battleground is sodden. Large pools of water formed by craters made by exploding shells abound making life that much worse, if that was possible. We see a long line of soldiers trudging from right to left across the wet ground. Many are wounded with bandaged limbs and some of the able-bodied are carrying or helping their wounded comrades to return to a place of safety at the rear of the battle lines. For many it was to be their last battle and they are now just corpses. In the central foreground we see a skeletal-like corpse lying on his back and even in death, his left arm is still raised in a claw-like fashion, a gesture of pleading for help, whether it be from his comrades or God himself, but it was to no avail. In the right background we see flashes of artillery fire. The idea for this depiction came to Nevinson when he and another officer visited Passchendaele, close to the town of Ypres, the scene of many battles during the First World War. He wrote about his experience in his autobiography:

“…We arrived at Ypres, and while he went to the Officers’ Club I wandered on up towards the Salient and obtained notes and rough sketches for my painting, ‘Harvest of Battle…”

In a letter Nevinson wrote in 1919 to Alfred Yockney from the Ministry of Information he described what he saw:

“…A typical scene after an offensive at dawn. Walking wounded, prisoners and stretcher cases are making their way to the rear through the water- logged country of Flanders. By now the Infantry have advanced behind the creeping barrage on the right, only leaving the dead, mud, & wire; but their former positions are now occupied by the Artillery. The enemy is sending up SOS signals and once more these shattered men will be subjected to counter-battery fire. British aeroplanes are spotting hostile positions…”

by John Singer Sargent

(c.1919)

It is a sad and moving painting and reminds me of a work by James Singer Sargent, entitled Gassed, which I featured in My Daily Art Display on July 10th 2011. That work also depicted a line of wounded soldiers, blinded by mustard gas, trudging towards their field hospital.

by C.R.W. Nevinson (c.1917)

My final offering is another war painting by Nevinson which depicts the horrors of war. It is entitled Paths of Glory and was completed by him around 1917. In the painting we see the corpses of two dead British soldiers lying face down in the mud among barbed wire. They have been left behind and their bodies are awaiting collection, identification and then their nearest and dearest will be informed of their fate. Besides them lie their helmets and rifles now no longer any use to them. Nevinson chose the title for his work, a quote from Thomas Gray’s famous poem Elegy Written in a Country Church-Yard

The boast of heraldry, the pomp of power,

And all that beauty, all that wealth e’er gave,

Awaits alike th’ inevitable hour:-

The paths of glory lead but to the grave.

There is of course a difference in the circumstances of death between Gray’s corpses who lay buried and at peace in a church graveyard and Nevinson’s corpses which lay abandoned on the battlefield.

Nevinson’s depiction of the two dead soldiers lying abandoned in a foreign field was just too much for the British Board of Censors, for the war was still raging in France and scenes like this would have a terrible affect on the morale of English people and so they did not want the work exhibited at the Leicester Galleries in Leicester Square, London. Nevinson rebelled and included the painting in the exhibition but placed a wide brown strip of paper across the work with word “censored” written upon it. The establishment was very unhappy by Nevinson’s apparent disregard of their dictate and he was publicly reprimanded, firstly for exhibiting a “censored” work and for the audacity of writing the word “censored” across the brown strip. As always, there is no such thing as bad publicity and the notoriety he gained from his audacious behaviour brought him to the attention of the public. The painting was bought by the Leicester Galleries.

In my next blog I will conclude Nevinson’s life story and look at some of his non-war paintings which first attracted me to him.

—————————————————————————–

Most of the information and facts for this blog came from books which I have mentioned as well as the excellent Spartacus Educational website.