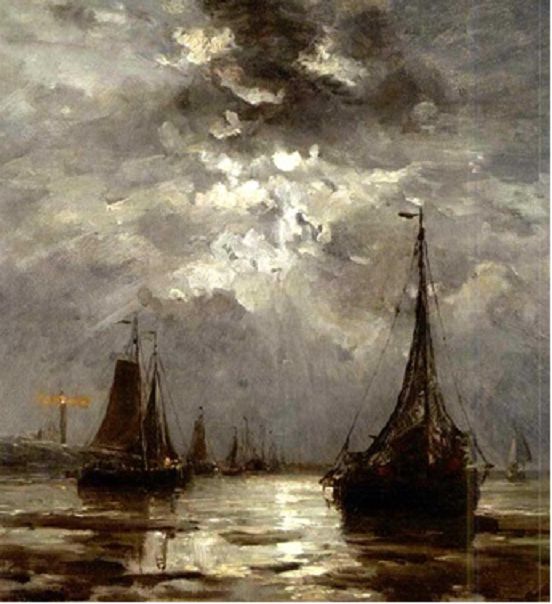

My featured artist today and over the next two blogs, is the Dutch nineteenth century landscape painter Charles Henri Joseph Leickert. His painting genre was also often associated with another artistic “-ism”, that of Romanticism. But what is Romanticism when used as a description of an artist’s work. In his 1950 book De Romanesken, the Dutch art writer, Frans Hannema described Romanticism in art as:

“…A great emotive stirring of the heart; an all enveloping expansion of feeling; a controllable urge for the whimsical, the grotesque, the fantastic and the eerie; a boundless desire and self-imposed hardship; a fantastic devotion and passionate contempt; an unfathomable nostalgia for the transience of all happiness and for the inconstancy of all things; a flight from circumscribed reality to the interminable dream: these are the fiercely jostling and often contradictory emotions with which the soul of the Romantic individual is affected…”

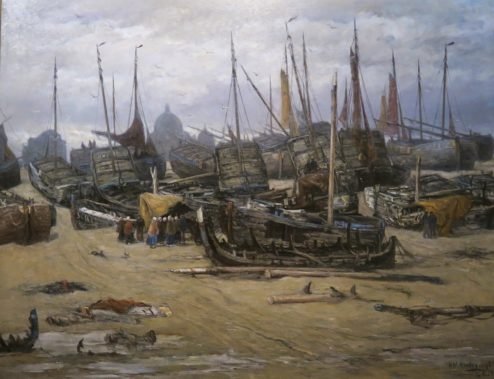

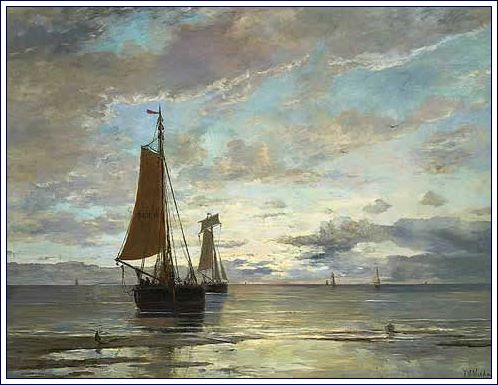

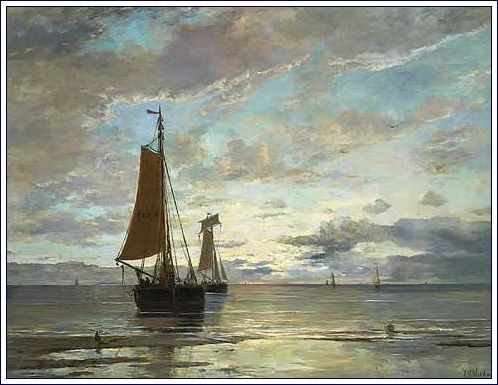

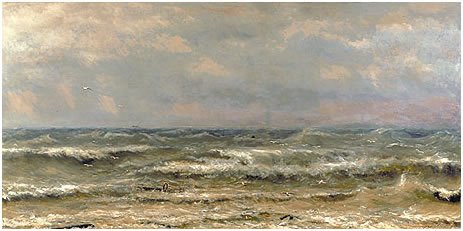

However, Romanticism in art was not that evident in Dutch paintings of the time. The leading Romantics of the nineteenth century were the Frenchman, Théodore Géricault, and Eugene Delacroix and the German Caspar David Friedrich. Dutch paintings in the early nineteenth century were generally limited to landscapes and cityscapes. The favourite Dutch artists of the time were from the bygone days of the seventeenth century such as Jan van Goyen, Salomon van Ruysdael, Jacob van Ruisdael, and Isaac van Ostade. Unlike the Romantic depictions of forests and waterfalls depicted in Jacob van Ruysdael’s works, Leickert preferred to depict everyday Dutch village and river scenes with their picturesque embankments or winter scenes featuring frozen canals on which people would be seen skating, and the frozen rivers and canals would often be overlooked by windmills. However, the Romantic title associated with Leickert was probably due to his ability to saturate his scenes with what is almost a supernatural light which was so prevalent in his depictions especially those featuring the evening sun.

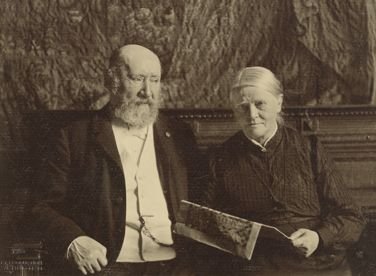

So why is Leickert not a well-known Dutch artist? Some historians believe the answer lies with his character. He was a shy person and often hid his light under the proverbial bushel. The bushel being his mentor and teacher, Andreas Schelfhout, whose shadow Leickert was pleased to remain under. The subject of Schelfhout’s works was very similar to that of Leickert or maybe that should be seen the other way around! Andreas Schelfhout was a Dutch painter, etcher, and lithographer, known for his landscape paintings. Schelfhout belonged to the Romantic movement and his Dutch winter scenes with frozen canals and skaters were already famous during his lifetime.

Charles Leickert was born on September 22nd, 1816 in Brussels. His parents were, his father Henricus Michael Leickert who had been born in Wittendorf, Germany in 1781 and his mother, also German-born, Henrietta Frederique Martilly. Leickert’s parents, who were married in Berlin, lived there until 1815, at which time with the defeat of Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo and the subsequent ending of the First French Empire, the French were driven out of the Netherlands and Leickert’s father, mother, and his eldest sister, two-year-old, Louïze Frederica, moved from Berlin to Brussels.

Leickert’s father gained employment as the King’s chamberlain (valet de chambre) at the court of King Willem I. At this time, and until 1820, the Kingdom of the Netherlands had twin seats of government, The Hague in Northern Netherlands, and Brussels in Southern Netherlands and so Henricus Leicker, as part of the royal entourage, had to move with his family backwards and forwards from one city to the other. In 1816 Charles Leickert was born in Brussels while some his younger siblings were later born in The Hague. Finally, around 1820 The Hague was designated as the sole capital of The Netherlands and the Leickert family made their home there. With the defeat of Napoleon and the ending of the French annexation of the Netherlands thousands of people came to live in the country and the population of The Hague swelled. The surge in population led to housing shortages, poor sanitation and disease which led to a large rise in infant mortality. The Leickert family were hit hard losing most of their children before they reached adulthood, some due to typhoid and tuberculosis and his three-year-old brother died of his burns in a fire.

Charles Leickert managed to survive and when he was just twelve years old, because he was showing talent as an artist, his father enrolled him into The Hague Drawing Academy in 1827. The tutor who had the most influence on Leickert was the Dutch landscape and cityscape painter, Bartholomeus van Hove. In 1828, a year after his enrolment, Charles Leickert’s father Henricus died. The cause of death was given as verval van krachten which simply means a decline in strength which seems very unusual as Henricus was just forty-five years old, but it could have been “part and parcel” of the poor sanitary conditions of the city at the time. Leickert’s mother Henrietta was left to bring up the family but struggled financially as her poor health meant she could not work. She pleaded successfully with the art academy to give her son artistic tuition for free, a decision which says a lot for Leickert’s talent. With no money to pay the mortgage, the king stepped in and bought the house of his one-time servant and Henrietta, along with Charles and his two sisters, Adelheid and Barbara, moved into rented accommodation. The health of Leickert’s mother continued to deteriorate and she eventually died in 1830.

Charles Leickert’s mother was a great believer in her son’s talent as an artist and she wrote a short poem in one of his sketchbooks as a testament to her belief that one day he would become a great painter. A translated version of her poem is:

Accept this booklet, little Lijket

And fill it with sweet studies

Improve your judgement, and the little heart

That burns with love so sweet for art

With little skills, free from small sorrows

May life flit by till death draws nigh.

Walk in the little field and in small nature

Observe and draw each little hour

Every little object, be it great or small

And great you shall one day be as artist.

Charles then 14 years of age, Adelheid aged 10 and Barbara aged 12 were placed in the Civic Orphanage. Their older sister Louïze, who was eighteen, had her own home as a live-in domestic. Although being consigned to an orphanage seems harsh, it had its benefits. Sanitation was good, the children were inoculated against infections which were killing many children at the time and they were fed and clothed. Life in fact for the children was quite good, and for Charles, being the son of the former First Chamberlain to the King, he was allowed to carry on his art lessons at the Drawing Academy. Art played a part in the orphanage and the children were encouraged to try out art and the most talented would attend painting classes which were funded by charitable bequests.

It is known, through his biographer, Johannes Immerzeel, that Charles Leickert’s first art teacher was Bartholomeus van Hove who ran a flourishing studio as well as teaching at The Hague Drawing Academy. Whilst under van Hove’s tutelage, Leickert honed his drawing skills and the art of chiaroscuro. The term chiaroscuro derives from the two words chiaro bright (< Latin clārus) + oscuro dark (< Latin obscūrus) and describes the prominent contrast of light and shade in a painting, and how the artist by managing the shadows is able to create the illusion of three-dimensional forms.

…………….. to be continued

Most of the information for the three blogs on Charles Leickert came from excellent 1999 book entitled Charles Leickert 1816-1907: Painter of Dutch Landscape by Harry J Kraaij