The pleasure the sea and the shoreline brings to us.

Having looked at Marine Art with depictions of mighty sailing ships in Part 1., and the plight of fishermen and lifeboatmen battling raging seas in Part 2., this third and final part will concentrate on the tranquillity of the sea and the shoreline A and how people enjoy the elements.

When I was last in Madrid and had spent a few days and many hours in the main Museums of Art, such as the Prado, Thyssen-Bornemisza and the Museo Reina Sofia, I decided to visit the Sorolla Museum, featuring work by the Spanish artist Joaquin Sorolla as well as by members of his family such as his daughter Elena.

Strolling along the Seashore by Joaquin Sorolla (1909)

Sorolla completed a number of beautiful works featuring the serenity of simply walking along a beach. It is an abnormally large square canvas (200 x 208cms) for a seascape work with life-sized figures. The two figures are of his wife, Clotilde and his daughter Maria as they walk along the Playa de El Cabanyal beach in their hometown of Valencia. Both women wear long white sundresses. There is an air of elegance and sophistication regarding mother and daughter and they appear to be members of the upper class whiling away their time at the beach on a beautiful summer’s day. Because of our viewpoint we do not see the horizon and the background is the sea with white foam atop the waves. Sorolla has used many shades of blue to depict the shimmering sea.

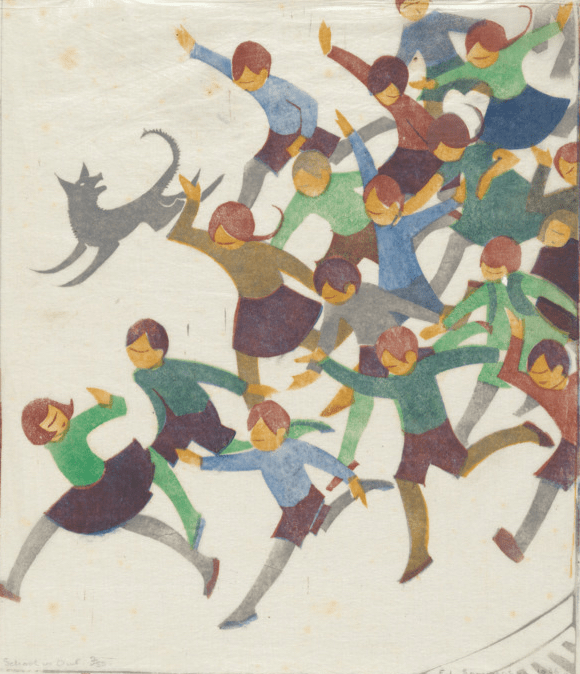

Running Along the Beach, Valencia by Joaquin Sorolla (1908)

Nothing expresses happiness and excitement more than children running along the shoreline without a care in the world. Sorolla’s painting entitled Running Along the Beach captures the energy and movement of the three children as they race along the water’s edge. The city of Valencia and its beaches were Sorolla’s great loves despite the fact that he resided in Madrid. He spent many hours at the beach painting en plein air capturing the effects of the beautiful Mediterranean sunlight.

Summer’s Day on Skagen’s Southern Beach by Peder Severin Krøyer (1884)

Boys Bathing at Skagen, Summer’s Evening by Peder Severin Krøyer (1899)

From looking at the marine/seascape paintings they produced, life at Skagen in Denmark must have been an idyllic way for the artist colony painters and their families to relax and enjoy their lives.

Summer Evening on Skagen Beach, Portrait of the Artist’s Wife by Peder Severin Krøyer (c.1899)

His painting, Summer Evening on Skagen Beach, Portrait of the Artist’s Wife, was part of Peder Severin Krøyer’s iconic, large scale ‘blue period’. Krøyer arrived in Skagen for the first time in 1882. Soon he became captivated by the light, the landscape and the simple lifestyle of the local community. He returned every year during the summer months, whilst spending the rest of the year travelling or in Copenhagen where he had his studio. In the summer of 1889, around the time he completed this painting, he had married Marie Triepeke, a Danish painter, whom he had had met in Paris, shortly after she arrived in the French capital in December 1888. Marie ran into Krøyer at the Café de la Régence, a favourite with the many Danish artists living in the city at the end of the 1880s. As Krøyer affection for Skagen grew, he began to take more of an interest in the vast expanses of sea, sand and sky. In the painting the two figures are set into a blue half-light, which was a favourite with the artists of the Symbolist movement.

Anna Ancher and Marie Krøyer going for an Evening Walk along Sønderstrand by Michael Ancher (1897)

A Stroll on the Bach by Michael Ancher (1896)

Another Skagen painter, who depicted the sea and shoreline was the Dane, Michael Ancher. He is renowned for his many works of Skagen’s fishermen and their battle with the harsh nature of the seas around Skagen, but he also produced paintings which highlighted the more tranquil side of life in the coastal town. When in the early 1890s Peder Krøyer painted his first blue-toned atmospheric pictures depicting Skagen South beach, Ancher was inspired by these images. In Ancher’s early paintings of Skagen from around the 1880s, the beach is first and foremost a place of work for the fishermen, but in the 1890s, Ancher saw the beach as becoming a promenade for the bourgeoisie, and in this work, this is just what Ancher has depicted. In the painting, A Stroll on the Beach, we see the merchant and counsellor, Lars Holst’s four daughters and a friend: In the front, Ida Holst, on the left, her sister, Anna Holst with her friend Elisabeth Bang, then Minne and on the right, Sophie Holst.

Eagle Head Massachusettes (High Tide} by Wilmslow Homer (1870)

Spending time at the beach can be a way of relaxing and clearing one’s mind of bustling city life. It can also be a place when one can enjoy solitude and try and rid our minds of things we strive to forget. This painting, Eagle Head Massachusetts (High Tide} was completed by American artist Wilmslow Homer in 1870. In 1861 his employer, Harpers, sent him to the front lines of the American Civil War, where he sketched battle scenes and camp life, the quiet moments as well as the chaotic ones. During his time as an illustrator for the magazine he witnesses the horrors of war and this painting was one of serene tranquillity which Homer had desired after his time at the Front. After the long war, he turned his focus to lighter scenes and started concentrating on fashionable young women. The High Tide painting is believed to be Homer’s most daring subject. It depicts three women on the beach having emerged from a swim in the sea. The woman in the centre rings out her wet hair, startling the small dog which looks on. The painting received mixed reviews with some focusing on issues of decorum and class, criticizing the women’s state of undress, despite the fact that they are wearing typical bathing costumes of the era. Another criticised how Homer had depicted the women as “exceedingly red-legged and ungainly”.

At the Seaside by William Merritt Chase (c.1892)

William Merritt Chase was the most important teacher of American artists around the turn of the 20th century. From 1891 to 1902, Chase served as the director of the Shinnecock Hills Summer School of Art in the town of Southampton, on Long Island, New York. The school and Chase’s stay on Long Island were organised by Mrs. Janet S. Hoyt, a wealthy patron of the arts and an artist who lived in the Shinnecock Hills. Chase taught two days each week and spent the rest of his time painting and enjoying the company of his family. In his painting, At the Seaside, we see women and children enjoying themselves on the beach, along Shinnecock Bay. It is a depiction of genteel leisure on a perfect day, at a perfect location. Chase has depicted a broad expanse of sky that fills the upper half of the canvas. We see the rushing clouds cleverly echoing the bright white forms of the children’s dresses and the Japanese-style parasols.

Crowd at the Seashore by William Glackens (1910)

William Glackens, known as an urban realist, favoured the crowded Coney Island beaches of New Jersey to depict the egalitarian throngs that came together there to relax and enjoy the sun and sea. The mass of figures depicted in his painting Crowd at the Seashore, suggested that the folk from New York and New Jersey who came were of mixed socio-economic backgrounds. Glackens desire to introduce liveliness into the work was achieved by using a vibrant palette. To heighten the scene’s energy, Glackens used a vivid palette and vigorous brushstrokes, and he added saturated oranges and blues to conjure up the midday sun’s heat and glare. William Glackens painted many pictures featuring beach scenes which became very popular.

Shadows on the Sea. The Cliffs at Pourville by Monet (1882)

Monet’s painting entitled Shadows on the Sea is an excellent example of Impressionism and we are able to observe the individual brushstrokes of the wave. Monet has depicted shadows, reflections and movements by a series of short, curved brushstrokes in pure, unmixed pigments. It is interesting to note how Monet has used pure colours such as yellow and turquoise blue on parts of the wave and placed them next to each other. Our eyes blend them from a distance and we begin to see green waves. The setting for the work is a hot summer day by the sea, and we note that the strong wind flowing across the water disturbs it, and it becomes a million small, flashing mirrors, which is exactly what Monet had hoped to convey.

Cliff Walk at Pourville by Claude Monet (1882)

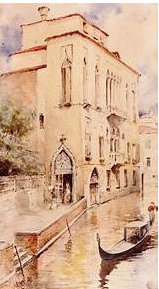

The Cliff Walk at Pourville is an 1882 work by Claude Monet and is currently part of the Art Institute of Chicago collection. Monet had a three-month stay between February and April 1882 at Pourville, a commune in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region in northern France, in 1882. He fell in love with the coastal town and the surrounding area and wrote to his future wife, Alice Hoschedé, extolling its merits:

“…How beautiful the countryside is becoming, and what joy it would be for me to show you all its delightful nooks and crannies…”

She was impressed by Monet’s enthusiasm and so they returned to Pourville in June that year. The painting features two ladies on the cliff above the sea who could well be Alice and her daughter Blanche. Many years later an X-ray of the painting indicated that the artist originally painted a third figure into the grouping, but later removed it. In John House’s 1986 book, Monet: Nature into Art, he talked about Monet’s marine art:

“…His cliff tops rarely show a single sweep of terrain. Instead, there are breaks in space; the eye progresses into depth by a succession of jumps; distance is expressed by planes overlapping each other and by atmospheric rather than linear perspective- by softening the focus and changes of colour…”

Figures on the Beach by Renoir (1890)

Another seaside scene I like was painted by Auguste Renoir in 1890 and entitled Figures on the Beach. The setting is thought to have been a beach on the Cote d’Azur in southern France. It is a sun-filled work in which we see two females at the beach, one shown in profile, sitting whilst holding a parasol on the sand, the other standing with her back to us holding a small wicker hamper. Besides the two female we also have a small white dog lying in the sand next to the seated woman. In the mid-ground we see a young boy dressed in blue standing by the water’s edge throwing stones into the sea.

Sea Bathing, the Beach at Étretat by Eugène Lepoittevin, (1864)

Sea Bathing in Étretat by Eugène Lepoittevin (1866)

My final two offerings featuring marine art and the way people enjoy their time on beaches and in the sea are from the French artist, Eugène Lepoittevin, who achieved an early and lifelong success as a landscape and maritime painter. In the upper painting entitled Les Bains de Mer, Plage d’Étretat (Sea Bathing, the Beach at Étretat), completed in 1864, we see a large group of people enjoying their day at the seaside. Of these figures some have been identified. They include the prominent French author, Guy de Maupassant (in blue cap at left), Charles Landelle, the French portrait artist, (in red cap, centre), and the French illustrator, engraver, Bertall (reading newspaper at right). The painting which was completed in 1864 was lost and only rediscovered in the last decade and was sold at Sotheby’s in Paris, in December 2020, for €226,800, a record for a work by Lepoittevin.

Sea Bathing, the Beach at Étretat is also the title of another of Lepoittevin’s works and was completed in 1866. The setting is the tranquil shores of Étretat, a place for plein air painting favoured by the artist. It had everything he wanted – pristine beaches and dramatic cliffs with its natural arches carved by the relentless seas. Add to this people enjoying the good weather and the opportunity to bathe in the clear water and the scene becomes idyllic.