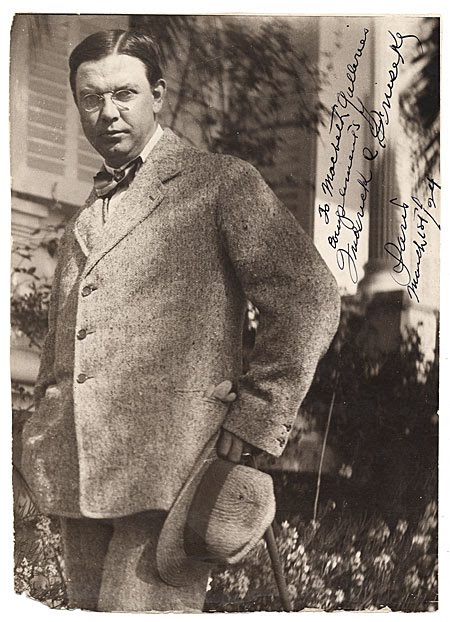

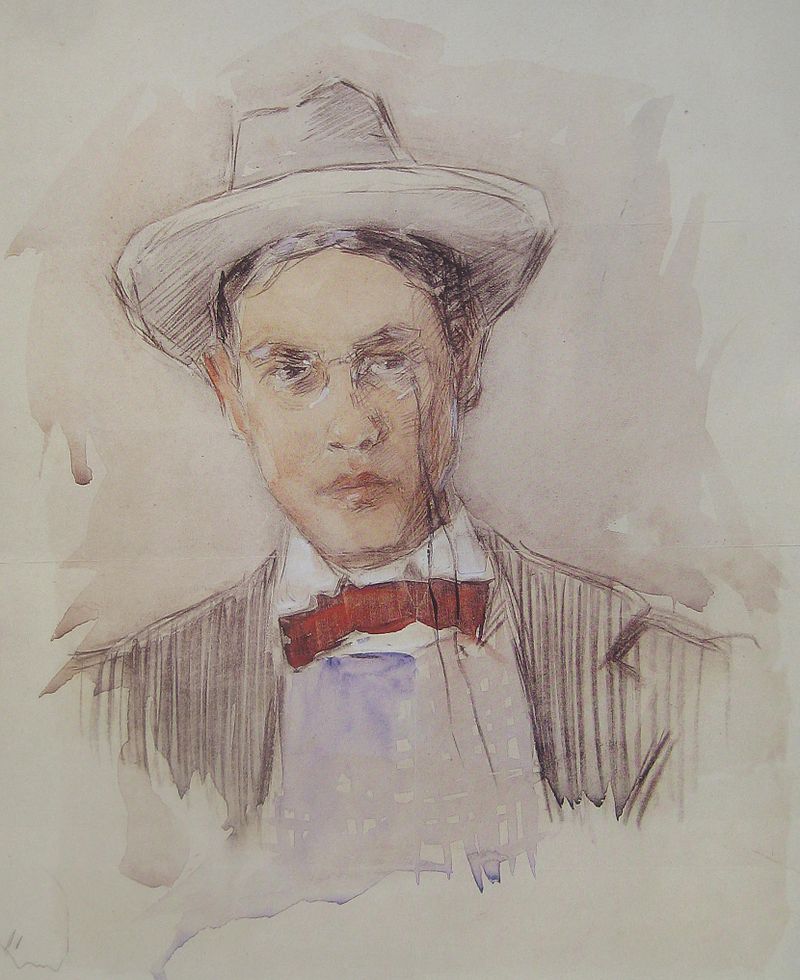

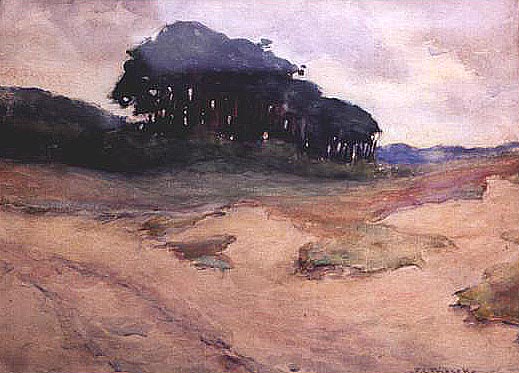

When my featured artist today had an exhibition of his work in London, the London Times summed up his works by saying “it must be seen to be believed”. In America the art critics designated him as “the magician of light”. His paintings are extraordinary. They are magnificent. Let me introduce you to the Russian landscape and staunch realist painter, Ivan Fedorovich Choultsé.

Sevanavank Monastery on Lake Sevan by Ivan Fedorovich Choultsé

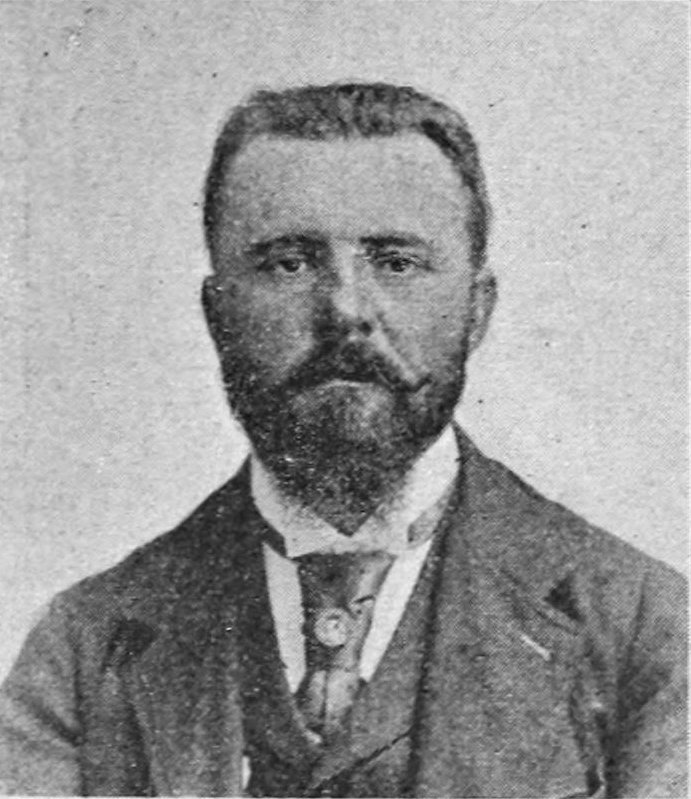

Ivan Fedorovich Choultsé was born in St. Petersburg on October 21st 1874. His ancestors hailed from Germany but emigrated to Russia in the eighteenth century. The original spelling of his family name, which was of German origin, was Schultze. His story was not one of a child dreaming of becoming a professional artist. His fascination at an early age was electricity and its production through hydro power especially the electricity generated by the Imatra waterfall in South Karelia. His interest in science was sated by an engineering education, although he continued to convey his creative side and during those early days as a teenager, he would spend his spare time painting small sketches. He headed up an engineering project in Finland but something went badly wrong and he lost all his money and was declared bankrupt.

Winter Sunset by Ivan Fedorovich Choultsé

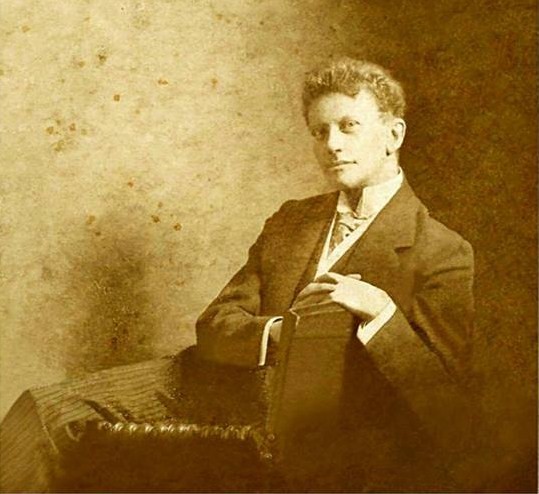

Ivan realised he had to earn money from another source and decided to concentrate on his drawing and painting abilities. Along with his early paintings which he had fortunately not discarded, he approached the academician, famous landscape painter and drawing teacher, Konstantin Yakovlevich Kryzhitsky, who had been a court painter to Tsar Nicholas II and was a painter of miniatures. His talent was apparent to Kryzhitsky and he enabled Ivan to be admitted to the Imperial Academy of Arts in St Petersburg. In addition to Kryzhitsky, Choultsé was influenced by other tutors, the Russian landscape artist Arkhip Kuindzhi and the Swiss landscape painter Alexander Kalam. In 1903 Choultsé held his first Academy exhibition which gained him early fame and recognition as a talented artist. His exhibition was a great success and he went on to exhibit his work at other major galleries in St. Petersburg and Moscow. He was eventually elected as a court painter to Tsar Nicholas II.

Park in Neskuchnoye by Ivan Choultse

In 1910 Choultsé embarked on an Arctic painting trip with Kryzhitsky. They visited the north of Norway and island of Spitzbergen. From that trip Choultsé produced a number of glorious paintings of the arctic landscape. In 1910 and 1911 Choultsé lost two of his most influential mentors, Kuindzhi in July 1910 and fifty-two year old Kryzhitsky who committed suicide in April 1911. Following the untimely death of Konstantin Kryzhitsky, Choultsé had his works shown at exhibitions which had been arranged by the society created by Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna, also a student of Konstantin Kryzhitsly, in his name. Choultsé frequently participated in its exhibitions that took place in the Grand Duchess’ palace on Sergeevskaya street in St Petersburg.

Silver Frost, Engadine, by Ivan Fedorovich Choultsé

Cholutsé reputation as a painter grew as did the sale of his work which was confirmed by the fact that the brother of Tsar Nicholas II, Mikhail Alexandrovich, regularly commissioned his works. In 1917 the Russian Revolution took place and for Choultsé he had to make an important decision. He was an academic painter and a supporter of the Academy system which meant staying in Russia under the new regime which was probably fraught with difficulty and so in 1917 he set off on a two-year trip of Europe. For those two years Choultsé was able to see and depict on canvas the beautiful landscapes of the mountainous regions of Northern Italy, Switzerland and Southern France where he painted the Mediterranean landscapes.

Vers Le Soir, Engadine’ by Ivan Fedorovich Choultsé

It could well have been the snowy Swiss landscape that brought back memories of his homeland or it could have been because he was mesmerised by the panoramic views of the likes of the long high Alpine valley region of Engadine and St. Moritz, but whatever it was, it profoundly affected Choultsé.

Choultsé finally settled back in Russia in 1921 as he still held out hope that he could remain a professional artist in his homeland under the new Soviet regime. He joined the Society of Individualist Artists in St. Petersburg and took part in the society’s first two exhibitions that year. After a while he lost hope that everything would be the same as it was in the pre-Revolution days and finally took the decision to leave his country of birth and go to Paris. He settled in the French capital in an apartment on the Boulevard Pereire, close to the Porte Maillot and it was here that the second stage of his career as a Russian immigrant began.

Choultsé artistic breakthrough in Paris came with his first solo exhibition of his work on November 23rd 1922, at the Galleries Gérard Frères. All fifty of his works were sold on the opening day of the show. This was extraordinary as the artistic environment of Paris was one of an over-abundance with all sorts of artistic offerings and gallery presentations. However, his success was indicative of the artist’s amazing talent. He became inundated with painting commissions and often did not have enough time to fulfil all the assignments.

There is no doubt that Choultsé was influenced by the the snowy Swiss landscape which probably reminded him of his native Russia. He said that he had fallen in love with the immense vistas of Engadine and St. Moritz. He was deeply moved by what he saw there and would concentrate on studying the effects of light on nature and by doing this created his best-known themes of beautiful snow-filled landscapes. In 1923, Ivan Fedorovich’s Choultsé’s paintings were exhibited in the Paris Spring Salon. His works were an amazing success with the public and the art critics alike and he was touted as the most admired artists of the Salon. With all success, there is an element of luck and Choultsé’s good fortune emanated from having contacts with good art dealers and owners of art galleries. He was represented by the gallery of Leon Gerard, which not only successfully sold his works of art but also regularly arranged his personal exhibitions. In 1927, Choultsé received his French citizenship.

Success in Europe was soon followed by success in America. In 1928, Choultsé met Eduard Jonas, who took most of Choultsé’s works to America. Jonas was a prominent figure in French and international art market, owner of exhibition halls and galleries both in Paris and New York, and also offered an exclusive plan of exposing Choultsé’s works in the States. Choultsé was delighted with the opening up of the American market. In a letter to his daughter, he wrote:

“…”I met a very interesting dealer. And how good it is that now, sitting in Paris, I can sell my work for dollars!…”

A contemporary of Choultsé, the Russian writer and critic, Nikolai Breshko-Breshkovsky wrote about the artist’s newly found fame and fortune in America:

“…In America, Choultsé’s snow and sun paintings are highly esteemed and worth of great price…”.

Although based in Paris, Choultsé regularly travelled to the Mediterranean and enjoyed painting many summer landscapes around the Côte d’Azur .

He also completed many paintings depicting scenes around the Italian coast.

In 1933 Choultsé moved his permanent residence to Nice. One of the last exhibitions of his work was in March 1936 held at the Breton Castle on rue Saint Antoine in Nice. Ivan Fedorovich Choultsé died in 1939, aged 64 and was buried in the Cimetière Caucade in Nice,

The Toronto dealer, G.Blair Laing, wrote in his 1979 book, Memoirs of an Art Dealer that Choultsé “painted spectacular snow scenes in which light seems to come from behind the canvas and glow”

In 1935 the New York Hammer Galleries held a jubilee exhibition entitled ‘150 Years of Russian Painting’ and described Choultsé’s reputation as “beloved among American collectors as a great master of snowy landscapes gilded by slanted sunbeams”.

For all my readers who celebrate this festive period may I wish you all a Merry Christmas.

![[Frieseke_Frederick_C_The_Garden_Parasol.jpg]](https://mydailyartdisplay.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/3712b-frieseke_frederick_c_the_garden_parasol.jpg)