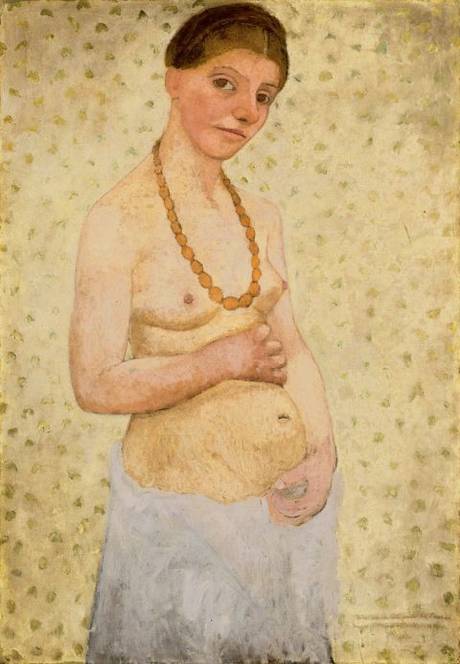

by Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun (1778)

I had intended this blog to be the concluding look at the life and some of the works of Élisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun but instead I am just concentrating this blog on a couple of the portraits Élisabeth did of the Queen consort Marie Antoinette and look at Élisabeth’s life up to her forced exile from France. My next blog will conclude Élisabeth’s life story.

At the end of my last blog we had reached 1775 and Élisabeth’s step father had retired from his jewellery business and the family had moved to an apartment in a large property, Hotel de Lubert, which was situated on the rue de Clery. The Hotel de Lubert was also where the painter and art dealer Jean-Baptiste Pierre Le Brun had his gallery. Soon after settling into her new home, Élisabeth took a great interest in the beautiful masterpieces which filled Le Brun’s apartment and gallery. She recalled this time in her memoirs saying:

“…I was enchanted at an opportunity of first-hand acquaintance with these works by great masters. Monsieur Lebrun was so obliging as to lend me, for purposes of copying, some of his handsomest and most valuable paintings. Thus I owed him the best lessons I could conceivably have obtained…”

Six months after moving in to her new home Le Brun proposed marriage to Élisabeth. She was not physically attracted to him but was concerned about her family’s financial future, hated living with her stepfather and after much persuasion from her mother, who believed Le Brun was very rich, agreed to Le Brun’s proposal. Even on her wedding day on January 11th 1776, Élisabeth had her doubts about the wisdom of her decision for she later wrote:

“…So little, however, did I feel inclined to sacrifice my liberty that, even on my way to church, I kept saying to myself, “Shall I say yes, or shall I say no?” Alas! I said yes, and in so doing exchanged present troubles for others…”

Élisabeth’s fears were soon borne out for although she termed her husband as being “agreeable” he had one great character flaw – he was an inveterate gambler and soon his money and that which Élisabeth earned from her commissions was frittered away. However before the money had run out, Élisabeth and her husband bought the Hotel de Lubert in 1779, and her Salons, which she held there became one of Paris’ most fashionable pre-revolutionary venues for artists and the literati. Two years later, on February 12th 1780, her only child Jeanne Julie Louise was born. In 1781 she and her husband left Paris and journeyed to Flanders and the Netherlands and it was during this trip that she saw some of the works by the great Flemish Masters and these paintings inspired her to try new painting techniques. During their time in Flanders she carried out various portraiture commissions for some of the nobility, including the Prince of Nassau.

It was back in the year 1779 that Élisabeth first painted a portrait of Marie-Antoinette, Louis XVI’s queen consort. It was at a time when the lady had reached the pinnacle of her beauty. In her memoirs Élisabeth described Marie-Antoinette:

“…Marie Antoinette was tall and admirably built, being somewhat stout, but not excessively so. Her arms were superb, her hands small and perfectly formed, and her feet charming. She had the best walk of any woman in France, carrying her head erect with a dignity that stamped her queen in the midst of her whole court, her majestic mien, however, not in the least diminishing the sweetness and amiability of her face. To anyone who has not seen the Queen it is difficult to get an idea of all the graces and all the nobility combined in her person. Her features were not regular; she had inherited that long and narrow oval peculiar to the Austrian nation. Her eyes were not large; in colour they were almost blue, and they were at the same time merry and kind. Her nose was slender and pretty, and her mouth not too large, though her lips were rather thick. But the most remarkable thing about her face was the splendour of her complexion. I never have seen one so brilliant and brilliant is the word, for her skin was so transparent that it bore no umber in the painting. Neither could I render the real effect of it as I wished. I had no colours to paint such freshness, such delicate tints, which were hers alone, and which I had never seen in any other woman…”

Both the artist and sitter formed a relaxed friendship and in her first portrait (above) the queen is depicted with a large basket, wearing a satin dress, and holding a rose in her hand. The painting was to be a gift for Marie-Antoinette’s brother, Emperor Joseph II, the Holy Roman Emperor, and a further two copies were made, one of which she gave to the Empress Catherine II of Russia, the other she would keep for her own apartments at Versailles. In all, Élisabeth painted more than thirty portraits of the queen over a nine year period

Élisabeth’s friendship with Marie-Antoinette and her royal patronage served her well as in 1783, her name had been put forward by Joseph Vernet for election to France’s Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture. As her morceau de réception (reception piece) she submitted an allegorical history painting entitled La Paix qui ramène l’Abondance (Peace Bringing Back Prosperity). She also submitted a number of her portraits. The Académie however did not categorise her work within the academy categories of either portraiture or history. Her application for admission was opposed on the grounds that her husband was an art dealer, but because of Élisabeth’s powerful royal patronage, the Académie officials were overruled by an order from Louis XVI. It is thought that Marie Antoinette put considerable pressure on her husband on behalf of her painter friend.

Having royal patronage and being great friends with Marie-Antoinette was a boon when the Royalty was loved by its people but once the people turned against Louis XVI and his queen, as happened during the French Revolution, then any friends the royal couple had were equally detested and at risk from the mob. Attacks on Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun’s character had started back in late 1783 when the newspapers wrote stories about an alleged affairs she had with the Finance Minister, Charles Alexandre, Vicomte de Calonne, the Comte de Vaudreuil and the painter François Menageot. The rumours persisted and it all came to a head in 1789 when fictitious correspondence between Élisabeth and Calonne was published in the spring. Rumours about her lavish lifestyle abounded, even though they were not altogether true. She was now starting to realise that having close connections to the monarchy, which she had once considered to be advantageous, was becoming a dangerous liability.

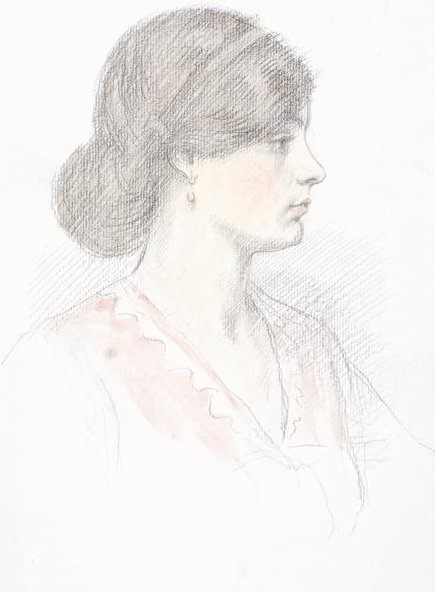

by Élisabeth Vigé Le Brun (1788)

Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun’s last portrait of Marie-Antoinette was completed in 1788 and entitled Marie Antoinette and her Children. The setting is a bedroom or a private chamber within the Royal palace. Marie Antoinette is seated with her feet on a cushion. This depiction of her posture symbolizes her status and high position in society. She has a young infant on her lap and her son and daughter are either side of her. In the painting we see her son, Louis-Joseph, Le Dauphin, standing to the right. Louis-Joseph suffered from bad health all his young life with the onset of early symptoms of tuberculosis and he died of consumption in 1789, a few months before his eighth birthday. On the Queen’s lap sits Louis-Charles, Duc de Normandie, who on the death of his elder brother, became the second Dauphin. Following the guillotining of his father Louis XVI, he became known as Louis XVII. This young boy was imprisoned in The Temple, a medieval Parisian fortress prison, where he died in 1795, aged ten, probably from malnutrition but rumour also has it that he was murdered. Standing on the Queen’s right is Marie Therese Charlotte de France, Madame Royale. She was Marie-Antoinette’s eldest child. She too was imprisoned in The Temple but was the only member of the Royal family to survive the ordeal. She remained a prisoner for over a year but Austria arranged for her release in a prisoner-exchange on the eve of her seventeenth birthday, in December 1795. In the painting we can also see depicted an infant’s cradle which Louis-Joseph points to and lifts the covers showing it as being empty. This empty cradle is a reference to Princess Sophie, Marie Antoinette’s other daughter, who was born in 1786 and died of convulsions two weeks before her first birthday. This very poignant painting still hangs at Versailles.

On the night of October 6th 1789, following the invasion of Versailles by Parisian mobs and the arrest of the royal family, Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun left the mayhem of Paris with her daughter and governess in a public coach and headed for Italy. She had hoped to return to France in the near future when the situation had settled down but in fact she never set foot back in France for twelve years.

My next blog will look at the latter part of Élisabeth’s life and I will regale you with my tale of infidelity which was the reason for featuring Élisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun in the first place !!