Among the most vibrant and spectacular works of the nineteenth century, were the sweeping landscape depictions of the Hudson River School which managed to capture the rugged beauty of the American countryside and wildernesses. The name Hudson River School was first used disparagingly by trendy Europhile critics who preferred the dignified depictions of the realism of L’École de Barbizon. The beautiful paintings of the Hudson River School compellingly convey the natural grandeur, not just of the Hudson River Valley, as the name would imply, but also the Catskills, Adirondacks, White Mountains, the Maritimes, the American West and South America. My guest artist was one of the great painters of that School.

Jasper Francis Cropsey

Jasper Francis Cropsey was born at Rossville, Staten Island on February 18th 1823. He was the eldest of eight children and his ancestors were of Dutch and Huguenot ancestry. His father was Jacob Rezeau Cropsey who had a farm in Rossville and his mother was Elizabeth Hilyer Cropsey (née Cortelyeu). During his early years, Cropsley suffered many bouts of ill health which resulted in him missing school and forced him to rest up at home. During those frequent periods of inactivity, he taught himself to draw. Many of his sketches featured architectural drawings and landscapes. Whilst attending the local country school he would help is father on the farm but in his pre-teen and teenage years he developed his main love, sketching and painting. Much to the chagrin of his teachers he would often be found doodling on his school books. In his 1846 unpublished biography, Reminiscences of My Own Time he wrote:

“…I was so disposed to adorn my writing book, on the margin, wherever there was a blank space, with fancy letters, boats, houses, trees, etc., and paint, or color the pictures in my books that I would undergo the reprimand of the teacher, rather than desist from it…”

The Valley of Wyoming, by Jasper Francis Cropsey (1865)

Cropsey as a young teenager was fascinated with architecture and this led him to assemble an elaborate model of a country house which he submitted to the 1837 fair of the Mechanics’ Institute of the City of New York and it won him a diploma. The model was well received and Joseph Trench, a New York architect who saw it, offered fifteen-year-old Cropsey a five-year apprenticeship in his architectural office. After eighteen months, Cropsey’s proficiency in drawing had earned him the responsibility for nearly all the office’s finished renderings. Cropsey prospered at the firm and during his penultimate year at the company he began painting the backgrounds of the architectural designs. To improve that skill, Joseph Trench persuaded his young apprentice to study watercolour painting with English-born watercolourist, Edward Maury. The firm even provided him with paints, canvas, and a space in which to study and hone his artistic skills.

The Narrows from Staten Island, by Jasper Francis Cropsey (1868)

Cropsey left the Trench’s office in 1842 and in 1843 he first exhibited a painting, which was quite well-received. It was a landscape entitled Italian Composition, probably based on a print he had seen at the National Academy of Design. Jasper Cropsey was elected an associate member of the Academy the following year and became a full member in 1851.

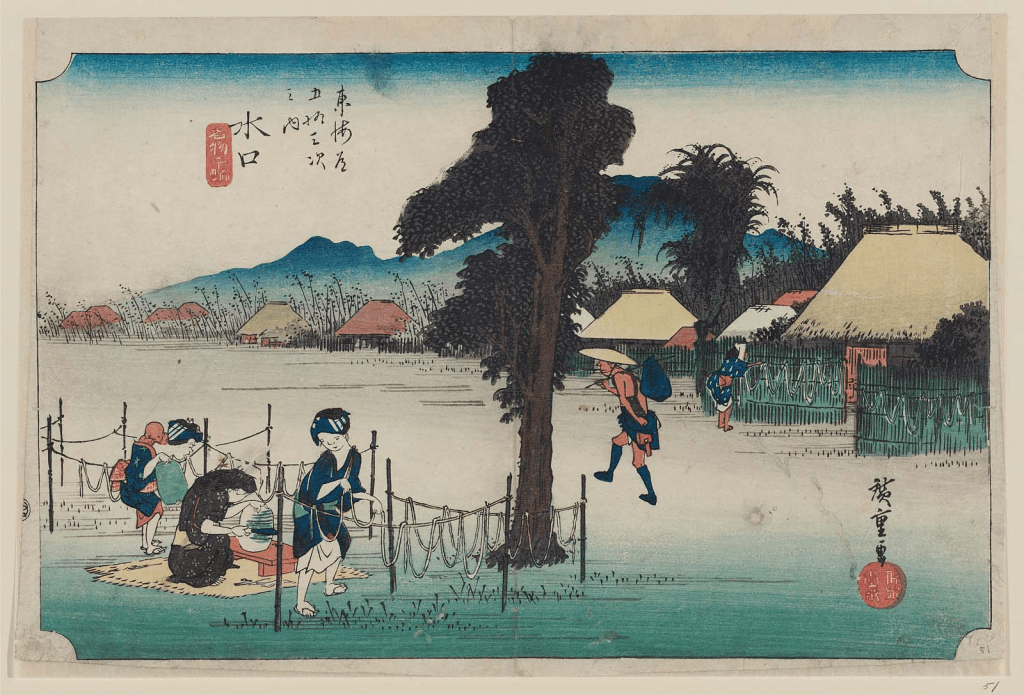

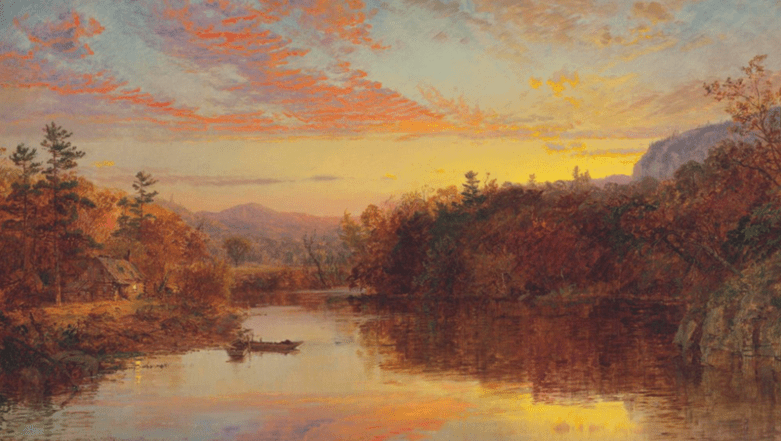

Sunset on Greenwood Lake by Jaasper Francis Cropsey (1877)

Having left the Trench architectural company Cropsey managed to support himself for the next two years by accepting commissions to provide architectural designs. Although that brought him financial support, his main love was sketching and painting landscapes and he would often take painting trips to New Jersey and Greenwood Lake, which straddles the border of New York and New Jersey. After one such trip, Cropsey had put together a number of sketches of the area, which on his return home he converted them into two paintings of Greenwood Lake that were accepted at an 1843 exhibition at the American Art Union.

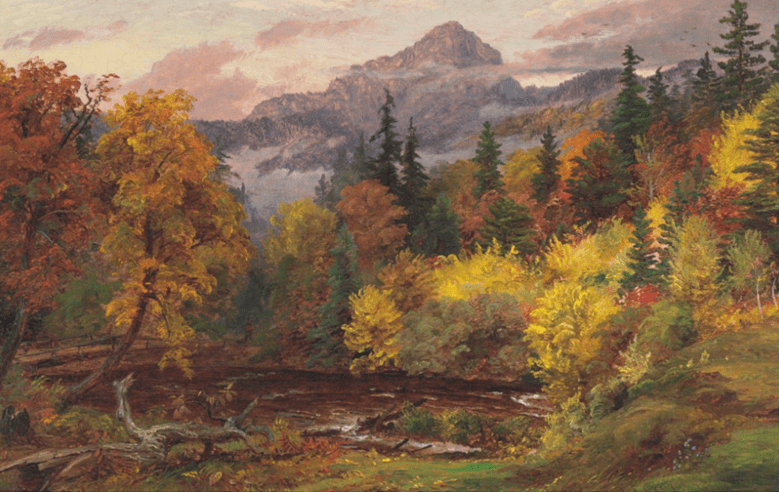

Autumn Foliage in the White Mountains (Mount Chocorua) by Jasper Francis Cropsey (1862)

During one of his trips to Greenwood Lake, Cropsey met Maria Cooley, whom he later married in May 1847. They went on to have two children, Mary Cortelyou Cropsey in 1850 and Lilly Frances Cropsey born in 1859. He and his wife crossed the Atlantic for a two-year European honeymoon and visited England during the summer of 1847, travelled throough France and Switzerland and reached Italy wheree the Cropseys spent a year among the colony of American artists who had settled in Rome. During that lengthy stay in Rome, Cropsey worked out of the former studio of Thomas Cole, the founding father of the Hudson River School. Cropsey became familiar with the works of the Nazarenes and other German artists in Rome and it was their influence which may have reinforced his own liking of detail in his paintings. Like many other American artists who visited Italy, Cropsey made frequent sketching trips to the Roman Campagna and other regions of Italy, such as Sorrento, Capri, Amalfi, and Paestum.

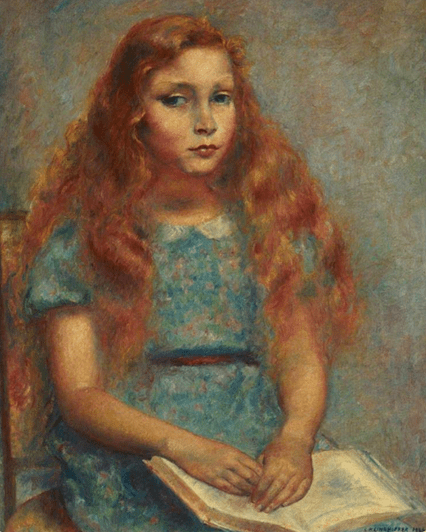

Maria Cooley Cropsy by Daniel Huntingdon (c.1850)

Cropsey and his wife returned to America in 1849 and he made his first trip to the White Mountains, a mountain range covering about a quarter of the state of New Hampshire and a small portion of western Maine. Cropsey rented studio space in New York which he shared with Edwin White, the Massachusetts-born artist, at 114 White Street in New York City. Here he taught and worked up his European sketches into finished oil paintings. Cropsey and his wife made their base in New York and from there in the summers they would make exploratory trips through New York State, Vermont, and New Hampshire, and he would continually sketch what they saw. Cropsey specialized in autumnal landscape paintings of the northeastern United States. He would convert sketches into finished paintings and sell them but also to supplement the family income he would teach.

Bayside, New Rochelle, New York by David Johnson (1886)

One of his pupils was the landscape painter David Johnson, who became a member of the second generation of Hudson River School painters.

Lord Byron’s Dream, by Charles Lock Eastlake (1827)

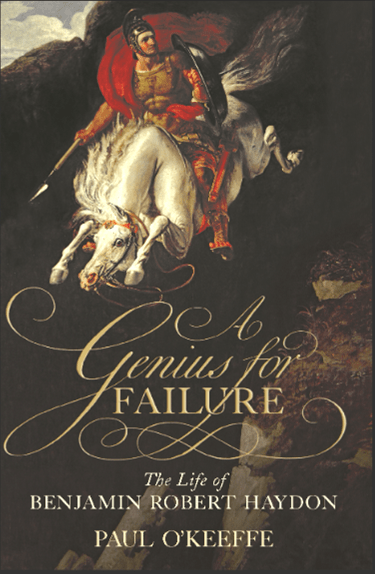

Cropsey and his wife made a second trip to England in 1856 and rented a studio in London at Kensington Gate. It was an ideal place to host parties and make friends such as the art critic John Ruskin, John Singleton Copley, 1st Baron Lyndhurst, who was a British lawyer and politician and was three times Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain and Sir Charles Lock Eastlake who was a British painter, gallery director, collector and writer of the 19th century. He became the first director of the National Gallery and from 1850 to 1865 he served as President of the Royal Academy.

Walton on Thames by Jasper Francis Cropsey (1860)

It was with friends such as these that ensured many English and American landscape painting commissions came Cropsey’s way from both English and American patrons. When Cropsey arrived in England he brought with him many commissions from his American patrons who wanted paintings depicting English castles and abbey ruins. He also found that there was a great interest amongst English clients for his American landscapes. The London printer Gambert and Company commissioned thirty-six views from Cropsey for publication in the American Scenery journal.

Autumn—On the Hudson River , 1860 by Jasper Francis Cropsey

In 1860 Cropsey completed one of his most famous paintings entitled Autumn—On the Hudson River of 1860. This monumental view of the Hudson River Valley was painted from memory and in-situ sketches he had made, in his London studio. Cropsey adopted a high vantage point, looking southeast toward the distant Hudson River and the flank of Storm King Mountain. It is an autumnal scene which would soon become Cropsey’s trademark. The work was praised by critics and the public alike, including Queen Victoria. The painting depicts a sweeping panoramic view of the river under a sun-streaked sky in this long, horizontal landscape painting (60 x 108 inches). The leaves on the trees are fiery autumnal oranges and reds. In the background we catch a glimpse of the mountains through the haze. At the bottom of the painting we can see vine-covered, fallen tree trunks and mossy grey boulders. At the bottom left we can just make out a trickling waterfall and small pool.

Although not easy to spot, on the bank of the pool, three men and their dogs sit and recline around a blanket and a picnic basket, their rifles leaning against a tree nearby. From our viewpoint, the land stretches down to a grassy meadow which is crossed by a meandering stream at the heart of the painting.

In the right foreground we see cattle on the riverbank drinking the water close to a wooden bridge.

Artist’s signature on flat rock

Cropsey signed the painting as if he had carved it into the flat top of a rock at the centre foreground of the landscape with his name, the title of the painting, and date: “Autumn – on the Hudson River, J.F Cropsey, London 1860.”

Summer, Lake Ontario by Jasper Francis Cropsey (1857)

Besides earning money from the sale of his landscape paintings he also provided illustrations for books of poetry by Edgar Allan Poe and Thomas Moore and did a series of views of American scenery published by Gambert and Company, London. Cropsy was acclaimed not only for his beautiful autumnal landscapes such as Autumn—On the Hudson River, 1860 which is now part of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. collection, but for bringing to the untravelled British people the exquisite scenery of the great Western continent. Queen Victoria was so impressed by Cropsey’s works of art that she appointed him to the American Commission of the 1862 International Exposition in London, and he subsequently received a medal for his services.

Coast of Genoa by Jasper Francis Cropsey (1854)

Cropsey and his wife returned to America in 1863. The 1860s were the most successful time for Cropsey as far as the sales of his work and his ever increasing bank balance. Shortly after their arrival home to America they visited Gettysburg to record the battlefield’s topography in a painting. Cropsey also began to accept architectural commissions once again and produced his best-known designs, such as the ornate cast and wrought iron Queen Anne-style passenger stations of the Gilbert Elevated Railway along New York’s Sixth Avenue.

High Torne Mountain, Rockland County, New York by Jasper Francis Cropsey (1851)

Cropsey’s father-in-law, Isaac P. Cooley was a justice of the peace from 1837 to 1839 and became a judge over the New Jersey Court of Common Pleas in 1840. Cooley later became a member of New Jersey State House of Assembly from 1860 to 1861. Cooley offered to build his daughter and son-in-law a studio on his estate but Cropsey declined the offer and instead, purchased forty-five acres of land near Greenwood Lake in Warwick, New York, where he designed and built a 29-room Gothic Revival mansion with its own studio which he called Aladdin. The family then divided their time between living in New York City, and spending time in Warwick.

The Old Mill by Jasper Francis Cropsey (1876)

Unfortunately for Cropsey, the art of the Hudson River School began to lose its popularity and by the early 1870’s would be completely out of favour in the art world. In 1876 Cropsey completed his last major work, The Old Mill, which is now part of the Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk, VA. Collection. The painting is a depiction of the Sanford gristmill, which stood on the banks of the Wawayanda Creek near Warwick, New York, and close to where Cropsey had built his palatial estate, Aladdin. The rural water mill was at the heart of the American pre-industrial economy, but time moved on and in the 1870s, the water mills were quickly being replaced by more efficient steam-powered mills and factories. This loss of such bygone icons concerned Cropsey. For him, it was symbolic of the loss of the simple past. It was a sentimental bereavement. The depiction was typical of Cropsey’s past output – autumn landscapes that beautifully captured the sunlit atmosphere of autumn in New York and New England. Cropsey exhibited it at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, where he was awarded a medal for “excellence” in oils.

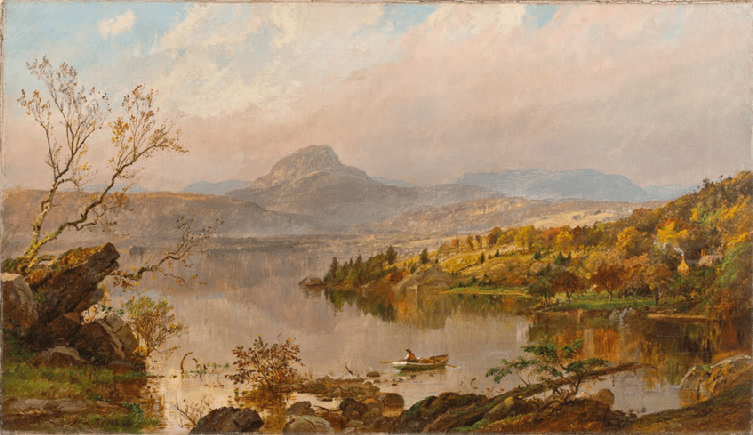

Wickham Pond and Sugar Loaf Mountain, Orange County by Jasper Francis Cropsey (1876)

The Hudson River School artwork began to lose its popularity by the mid 1870’s and by the end of the decade would be completely out of favour in the art world. In the early 1880’s the sale of Cropsey’s landscape paintings was dwindling eclipsed in popularity by the smaller scale works which were, softer, mood-evoking landscapes of Barbizon-inspired painters such as George Inness. As a result the Cropsy family’s financial situation became dire and the family was perilously close to having their home, Aladdin, in Warwick, NY, taken from them. Fortunately, they managed to sell their lavish estate and at the same time, auctioned off many paintings, furniture, and household possessions in preparation to move to a smaller property.

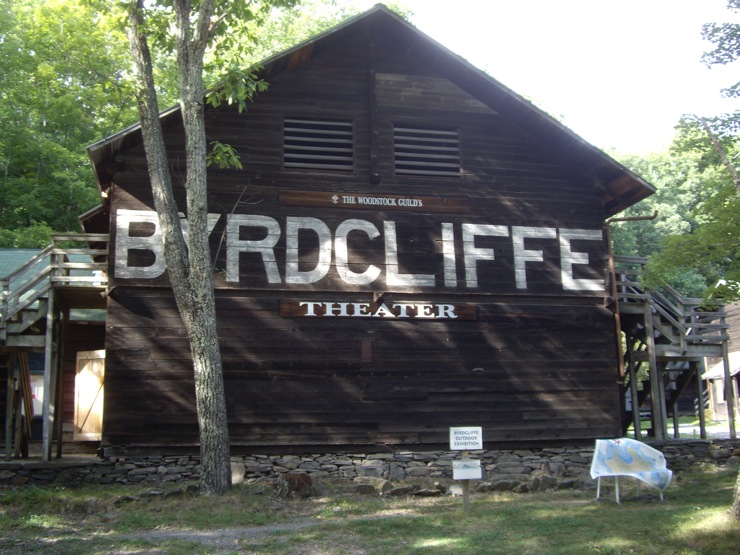

Ever Rest, 49 Washington Avenue, Hastings-on-Hudson

In 1885 the Cropsey family moved from Warwick to Hastings-on-Hudson, a village in Westchester County located in the southwestern part of the town of Greenburgh in the state of New York. He firstly rented a property then later bought a house at 49 Washington Avenue, which they named Ever Rest. Cropsey and his family lived there for the rest of their lives. They were content to live a quiet existence there at Ever Rest and did very little travelling. As far as painting was concerned Cropsey concentrated in depicting local views or views based on the hundreds of sketches he had completed through the years, including studies he did in the two year period spent in Rome. .

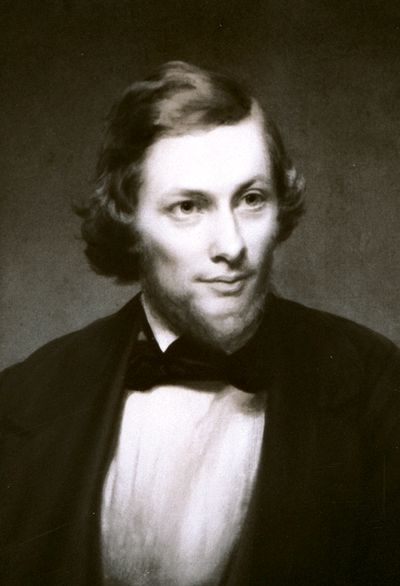

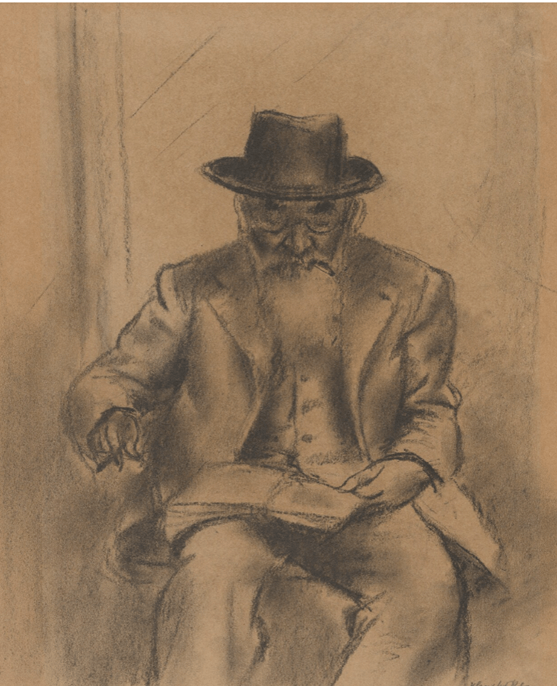

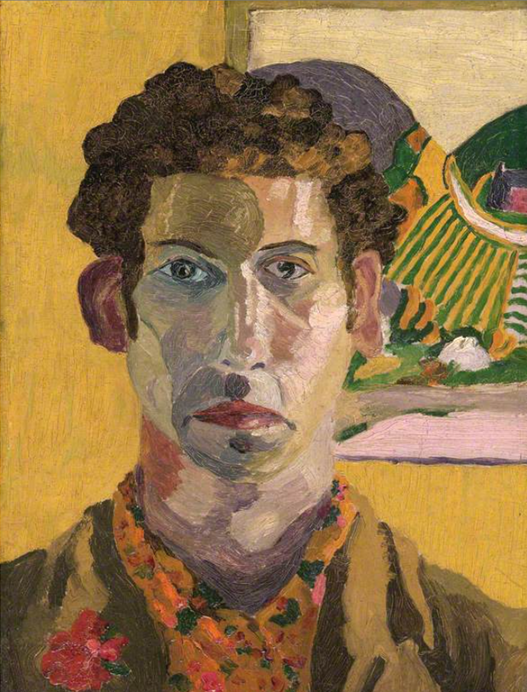

Jasper Francis Cropsey by Edward Mooney (1850)

Jasper Francis Cropsey suffered a stroke in 1893 and died at Ever Rest on June 20th 1900 at the age of 77, and Maria, his wife of 54 years, passed away in 1906.

The Cropsey home, known as Ever Rest, was built in 1835 and purchased by Jasper F. Cropsey in 1885. Cropsey extended Ever Rest by adding an artist’s studio to it in 1885. The Homestead is located at 49 Washington Avenue, Hastings-on-Hudson, NY. On May 17, 1973, both the New York and National Historical Societies declared the Homestead an historical site. The Homestead is listed in the “National Register of Historic Places in New York”.

A great deal of information I needed cam fro some excellent websites:

Welcome Autumn with Jasper Cropsey’s Colorful Landscape Paintings