I had planned that this single blog would be all about the American artist Thomas Eakins and I had decided on which painting I would feature. However whilst researching the life and works of this great painter I came across another painting of his which I fell in love with and decided that I could not pass up the opportunity of highlighting that particular work of art as well, so I have decided to split Eakins’ life story over two blogs which gives me the opportunity to feature not just one of his paintings, but two.

Thomas Cowperthwaite Eakins was born in Philadelphia in 1844. He was the eldest child of five children of Caroline Cowperthwait Eakins, whose ancestors were part English and part Dutch, and Benjamin Eakins, who was the son of a Scottish-Irish weaver. Thomas Eakins was brought up in a loving family environment and had a close and caring relationship with his father. Father and son both loved sporting activities and they would often go out swimming together in the nearby river and when the harsh winters set in and the river froze over they would go ice skating. It was also Thomas Eakins’ father who introduced him to the world of rowing, which he would enjoy as a sport and also depict in many of his paintings. His father was also very interested in art and had many artist friends and would spend much time discussing art with his son.

Benjamin Eakins was a calligrapher and writing master and as such would spend hours pouring over parchment documents which he had to inscribe. Thomas would watch his father at work and by the age of twelve became competent in line drawing, perspective and the grid work which was the needed in formulating designs and it was a technique that Eakins would sometimes use in his own artwork in the future. Thomas Eakins attended the Central High School, a public secondary school in Philadelphia. The school still exists to this day and is regarded as one of the top public schools in America due to its high academic standards. Here Eakins studied many subjects including mechanical drawing at which he proved an excellent student. In 1861, at the age of seventeen, Thomas Eakins enrolled at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art where he studied drawing and anatomy. In 1864 he transferred to the Jefferson Medical College where he once again studied anatomy and at one time considered the medical profession as his future.

In 1866, aged twenty-two, he travelled to Europe to study art and remained there for four years. Whilst in Paris he studied under the French realist painter Jean-Leon Gérome and worked as an apprentice at the atelier of the portrait painter, Léon Bonnat. It was under his tutorship that Eakins learnt the importance of anatomical accuracy in paintings and a technique he would adhere to in his own future works. He studied at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris but like so many who studied there he railed against what he looked upon as that establishment’s classical pretentiousness. He was also critical with regards the Academy’s treatment of nudity which was always couched in classical or mythological settings. In William Innes Homer’s 1992 biography of Eakins entitled, Thomas Eakins: His Life and Art, he quotes from a letter Thomas wrote to his father in which he expressed his criticism, he wrote:

“…She [the female nude] is the most beautiful thing there is in the world except a naked man, but I never yet saw a study of one exhibited… It would be a godsend to see a fine man model painted in the studio with the bare walls, alongside of the smiling smirking goddesses of waxy complexion amidst the delicious arsenic green trees and gentle wax flowers & purling streams running melodious up & down the hills especially up. I hate affectation…”

From Paris he travelled to Spain and became influenced by the works of the great Spanish painters such as Velazquez and Ribera which he saw in the Prado. He returned home to Philadelphia in 1870 and set about working on a series of oil paintings and watercolours, which featured rowing scenes and portraits of champion rowers. However this depiction of such a modern sport in paintings was reported to have shocked the more staid and conservative local artistic establishment.

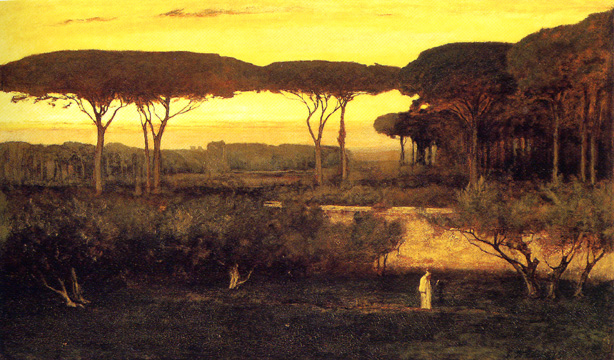

The featured painting in My Daily Art Display today is one of this series of paintings featuring rowing scenes. It is entitled The Champion Single Sculls sometimes known as Max Schmitt in a Single Skull and was completed by Thomas Eakins in 1871. The setting is the Schuylkill River that meanders quietly through Philadelphia and which is an ideal venue for rowing. The central figure in this painting is the champion oarsman, Max Schmitt, a childhood friend of Eakins and who, like Eakins, had attended the Central High School. Max Schmitt, a lawyer, was by far the best oarsman in Philadelphia at the time and had won, against formidable opposition, the first ever single skulls championship on the Schuylkill in 1867 and his friend Eakins sent him a congratulatory telegram from Paris.

The painting is not of the race itself but simply depicts the moustachioed Schmitt taking a break from his training session. The rower rests and turns to face. His oars cause a ripple on the surface of the river as they continue to skim across the water. Schmitt and his racing scull are reflected on the mirror-like surface of the river. To become a successful oarsmen one needs to have upper body strength and we can see how Eakins has depicted the toned muscular torso of Schmitt.

In the middle ground of the painting we see another oarsman and this is Eakins himself, who is rowing at speed away from us. His name and the date are inscribed on his boat but it is difficult to make this out in the attached picture. The name of Schmitt’s scull is much easier to read. It is Josie which was named after his sister. Another rowing boat can be seen in the background with its two rowers and a coxswain all of whom are wearing Quaker clothes. Just beyond them we see the stone arches of the Connecting Railroad Bridge with a steam train just about to cross its span. Further back is the first Girard Avenue Bridge, behind which we can just make out a steamboat chugging up the river.

Although at first glimpse we presume the setting is somewhere in the countryside, it is not, as the Schuylkill River runs through Fairmount Park, which at the time was the largest urban park in America and would be the site of the 1876 Universal Exposition.