My blog today starts with a caricature of Gottlieb Biedermeier. Gottlieb is not the artist of the day. He is just the lead-in to the star attraction. Gottlieb Biedermeier, more commonly referred to as Papa Biedermeier, used to appear as a cartoon character in the popular newspaper, Fliegende Blätter, a German weekly non-political humour and satire magazine which appeared between 1845 and 1944 in Munich, and it is through his regular appearance that this period was actually termed the Biedermeier era, an era which stretched between the defeat of Napoleon in 1815 and the Republican revolts against European monarchies of 1848, which began in Sicily, and spread to France, Germany, Italy, and the Austrian Empire. Papa Biedermeier was a comic symbol of middle-class comfort. The art of the Biedermeier period came to be characterized by what art critics of the period termed “rigorous simplicity.” The works of art often had an enamel-like finish that masked individual brushstrokes. Landscape and portraiture grew in importance while history painting declined. In painting, the Biedermeier style reflected the bourgeois, simple, joyful, affable and conformist environment, enhanced the aesthetics of the natural beauty and has influence on contemporary art and design.

In Austria painters during this time portrayed a sentimental and virtuous view of the world but in a realistic way. The German word best describing the emotions derived from the art is gemütlichkeit, which is a space or state of warmth, friendliness, and good cheer. Other qualities of gemütlichkeit include cosiness, peace of mind, belonging, and well-being. In other words, a “feel good” factor and such comfort, as depicted, emphasized family life and private activities, especially letter writing and the pursuit of hobbies. No Biedermeier household was complete without a piano as an indispensable part of the popularized soiree. Soirees perpetuated the rising middle class’s cultural interests in books, writing, dance, and poetry readings—most subject matter for Biedermeier paintings was either genre or historical and most often sentimentally treated. The leading Austrian exponent of this type of art is my artist of the day. He is Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller.

Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller was born in Vienna in January 1793. In 1807, at the age of fourteen, Waldmüller studied Fine Arts at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna under the Austrian painter, draughtsman, and well-respected teacher, Hubert Maurer, who had been teaching art at the Academy since 1785. Waldmüller remained there until 1811. Waldmüller then went to Presburg in Hungary to study portraiture. Following that he worked in Croatia as a drawing teacher for the children of the Count Gyulay, the governor of Croatia before returning to the Academy in 1813 to carry on with his artistic studies, this time concentrating on portraiture.

Whilst in Vienna Waldmüller would visit the court and municipal galleries where he would make copies of the Old Masters.

One example of this is his version of Juseppe de Ribera’s Martyrdom of St Anthony which the Spanish artist completed in 1628 which is now in the Szépmüvészeti Museum in Budapest. St. Andrew was St Peter’s brother and preached around the Black Sea Area. According to legend he was crucified on two pieces of wood which formed an “X” which has since become known as the cross of St Andrew.

Waldmüller’s copy of the painting can be seen in the Akademie der bildenden Künste in Vienna. Waldmüller had hoped to sell the copies he made of the paintings of the Old Masters but the income from this venture was insufficient for him to live and support himself.

In 1814, Waldmüller married a well-known Austrian opera singer, Katharina Weidner and he worked as a scenery designer at the various venues at which his wife was performing. He took up the role as professor of art at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna and in 1823 exhibited for the first time at the Vienna Akademie.

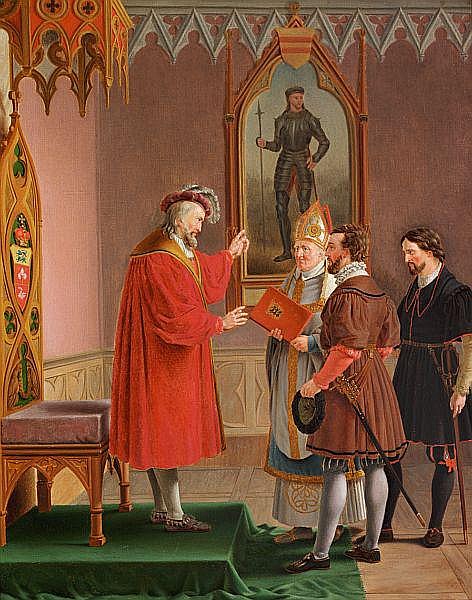

For the next decade he travelled around Europe, enhancing his reputation as a leading portraitist of his time and in 1827. He received royal patronage following his portrait of the nineteen year old Franz I, who would become the Holy Roman Emperor in 1845.

His art at the time concentrated on portraiture, an art genre in which Waldmüller excelled. His portraits had a high smooth-finish and decorative detail and were often compared to the French Neo-classical painter Ingres. One of his most beautiful portraits is entitled Portrait of a Lady, which he completed in 1820.

One of the most famous of his sitters was Ludwig van Beethoven who sat for him in 1823. The portrait had been commissioned by the Leipzig publishers Breitkopf & Härtel. According to notes and letters, it was a one-off sitting and even that was interrupted. So in the short time he had, Waldmüller only portrayed Beethoven’s face, and it was later, back in his studio, that he added the clothes and probably also parts of his hair. The original was destroyed in 1943 but fortunately, the portrait was so popular in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century that it was reproduced and copied many times.

Perhaps, one may consider his portraits of children a little too “syrupy” but this should not detract from the excellent portraits. In 1835, Waldmüller, whilst living in Vienna, completed a commission to paint the portrait of seven year old Julia Aspraxin, the daughter of Count Alexandr Petrovich Aspraxia, a serving Russian in Vienna.

In 1832 he painted a portrait of the two-year-old Franz Josef, the future Austrian Emperor entitled Portrait of the Future Emperor Franz Josef I of Austria as a Grenadier with Toy Soldiers. The child posed for the artist in the uniform of a grenadier along with some similarly dressed Hungarian wooden figures. It is like a state portrait on a miniature scale. The child, with his blue eyes, looks out innocently unaware of his future role and the disasters that would follow.

Waldmüller painted pictures of all genres and had soon built up his standing as a talented landscape painter. His beautiful landscape artistry was appreciated by the public and in the 1850’s he became very interested in the depiction of sunlight and the contrast between light and shadow which one realises was a pre-cursor to Impressionism. I especially like his 1831 paintings featuring the elm trees in Prater, the large park in Vienna. One was entitled Old Elms in Prater. Look at the extraordinary detail.

The other simply, Elms in the Prater. His landscape artistry was based on his strong belief that art should be determined by the careful and meticulous examination of nature. For Waldmüller, a talented colourist and someone who had a great knowledge of nature, it was all about natural observation achieved by plein air painting and not so much the way art was taught in academies. It was, like the Impressionists, fifty years later, about the effect of light.

Another beautiful landscape work was his 1838 painting entitled View Of The Dachstein With The Hallstättersee From The Hütteneckalpe At Ischl.

He became the curator of the Gemäldegalerie of the Academy of Fine Arts in 1829, a post he held for almost three decades. However in 1849 and again in 1857, he wrote critical papers with regards the Academy and academic teaching of art and, at the age of sixty-four , was forced to resign from his position at the Academy.

The third “string” to Waldmüller’s artistic bow was his great talent as a genre painter. His genre paintings shied away from idealisation or pretentiousness and although he would often add historical and religious elements to his depictions he was never afraid to highlight social criticism in the paintings. Through his depictions of life in the countryside his paintings extolled the virtue of rural life and at the same time highlighting the positivity of family life. Such joyousness can be seen in his 1857 painting, Corpus Christi Morning. Life for the peasant class may not all laughing and dancing but for that moment in time life could not be better. It was a gemütlichkeit time.

Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller completed his painting Children decorating a Conscript’s Hat in 1854. The painting depicts a very poignant moment. It was an occasion of great importance to rural families. We see a group of girls, maybe his sisters, decorating the hat of a young man who has been called up to fight for his country during his compulsory military service. His hat is being decorated with flowers and ribbons. The decorating of the hat is a time of joy and merriment which masks the possible horrors the young man may encounter. As far as art is concerned, it is a masterpiece of evocative genre painting and, the work is a testament to how Waldmüller depicts the intricate interplay of light and shadow.

Another work by Waldmüller, The Depature of the Conscript, shows the family of a conscript saying their farewells and wishing him a safe journey. His mother places the decorated hat on the head of her son. Look how the boy wraps one arm around his mother whilst his other hand is held lovingly by his father. It is now that maybe they realise that the ceremony of decorating the hat will mean nought if their beloved son does not return home. In the background we see women in tears. A young man, maybe the conscript’s younger brother, looks back pensively at his older brother wondering when it will be his time to join the military. The conscript’s young sisters try to cling hold of him, not wanting him to go. This is not a scene of joy but one of realism, one of foreboding.

I have always loved genre paintings especially when there are numerous characters depicted. Each time I look at painting like this I discover something different.

In 1851, Waldmüller, aged 58, married his second wife, 25-year-old Anna Bayer. He carried on exhibiting his work at various exhibitions, including the prestigious World Exhibition in Paris and at the International Exhibition in London. In 1856 he travelled to London where he sold thirty one of his paintings to the royal household and court. By the 1860s, the Academy in Vienna had forgiven Waldmüller’s transgressions and outspoken views critical of their institute and their teaching methods and he was once again welcomed back to the Viennese artistic fold. He was knighted in 1865, shortly before his death that August, aged 72.

Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller is looked upon as one of the most important Austrian painters of the Biedermeier period. His superb artistic talent, as a landscape painter, was never questioned. He was an advocate of plein air painting, putting down on canvas what the eye could see. This to him was of greater importance than the art taught in academies. The way in which he achieved an accurate characterisation of the human face took his portraiture to another level. His genre works which depicted rural everyday life were outstanding. The depictions, often moralising and socially judgemental would set a marker for future artists who favoured this genre.

I give you Ferdinand Georg Waldermüller.

In 1936 he travelled to Paris with his latest works, which were to be exhibited in New York. When the Spanish civil war broke out, he decided to stay in Paris and his wife and daughter joined him. He lived and worked in an apartment at 98 Boulevard Auguste Blanqui, Paris and attended life classes at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, where he produced a large number of drawings. In the summer of 1939, with the onset of the Second World War he and his family left Paris and moved to Varengeville-sur-Mer in Normandy, where he rented a house and where the family remained until 1940.

In 1936 he travelled to Paris with his latest works, which were to be exhibited in New York. When the Spanish civil war broke out, he decided to stay in Paris and his wife and daughter joined him. He lived and worked in an apartment at 98 Boulevard Auguste Blanqui, Paris and attended life classes at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, where he produced a large number of drawings. In the summer of 1939, with the onset of the Second World War he and his family left Paris and moved to Varengeville-sur-Mer in Normandy, where he rented a house and where the family remained until 1940. At the end of May 1940 the Germans bombed Normandy and Miró decided to return to seek refuge in Spain with his family. His fame had by now crossed the Atlantic and in 1947 during his first trip to America, he produced a mural painting for the Gourmet Room at the Terrace Plaza Hotel in Cincinnati.

At the end of May 1940 the Germans bombed Normandy and Miró decided to return to seek refuge in Spain with his family. His fame had by now crossed the Atlantic and in 1947 during his first trip to America, he produced a mural painting for the Gourmet Room at the Terrace Plaza Hotel in Cincinnati. In 1956 Miró summed up his love of the Balearic Island:

In 1956 Miró summed up his love of the Balearic Island:

![View of the Capitoline Hill with the Steps that go to the Church of Santa Maria] d’Aracoeli) by Paranesi (c.1757)](https://mydailyartdisplay.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/view-of-the-capitoline-hill-with-the-steps-that-go-to-the-church-of-santa-maria-d_aracoeli-by-paranesi-c.jpg?w=840&h=632)

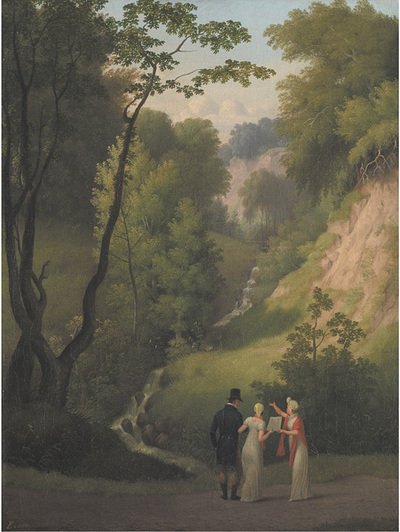

Another landscape Eckersberg completed in 1809 featuring the island was entitled The Cliffs of the Island of Møn. View of the Summer Spire. The chalk cliffs on the eastern coast of the island, known as Møns Klint, and the surrounding woodlands and pasture lands has attracted an estimated quarter of a million visitors every year and is the favourite location for artists as it was in the nineteenth century. Christopher von Bülow had his Nordfeld estate near the cliffs so this was probably the reason for Eckersberg depiction. It gave the artist the chance to depict the elements of nature which made the area so loved. The high white limestone peak we see in the background is the Sommerspirit or Summer spire which rises to a height of 102 metres. Unfortunately this natural wonder can no longer be seen as in January 1988 it crashed into the sea due to coastal erosion below its base. Maybe there is a touch of humour in the painting as we Eckersberg depicting a petrified woman shrink back from the edge of the cliff in fear, despite the soothing overtones from her male companion.

Another landscape Eckersberg completed in 1809 featuring the island was entitled The Cliffs of the Island of Møn. View of the Summer Spire. The chalk cliffs on the eastern coast of the island, known as Møns Klint, and the surrounding woodlands and pasture lands has attracted an estimated quarter of a million visitors every year and is the favourite location for artists as it was in the nineteenth century. Christopher von Bülow had his Nordfeld estate near the cliffs so this was probably the reason for Eckersberg depiction. It gave the artist the chance to depict the elements of nature which made the area so loved. The high white limestone peak we see in the background is the Sommerspirit or Summer spire which rises to a height of 102 metres. Unfortunately this natural wonder can no longer be seen as in January 1988 it crashed into the sea due to coastal erosion below its base. Maybe there is a touch of humour in the painting as we Eckersberg depicting a petrified woman shrink back from the edge of the cliff in fear, despite the soothing overtones from her male companion.