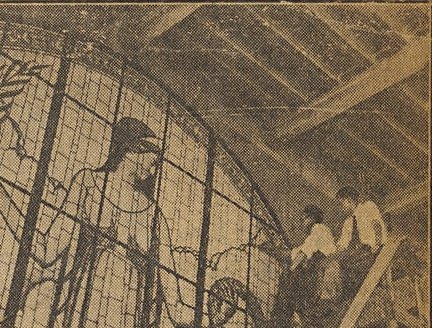

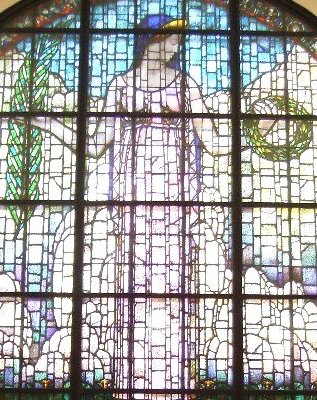

When Grant Wood spent time in Munich overseeing the production of stained glass for the memorial window for the Veterans Memorial Building in Cedar Rapids he had time to visit the city’s museums and he was inspired by the artistry of the painters from Netherlands, especially Jan van Eyck and the portraiture of the Renaissance artists.

Portraiture normally has a plain background so as not to detract from the sitter but often in Renaissance portraits a landscape background was used which would give you some knowledge about the sitter.

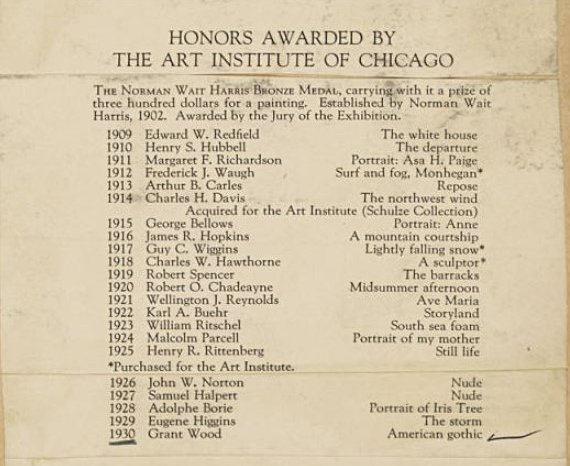

No doubt Grant Wood remembered that type of portraiture when he painted Woman with Plant in 1929. In this work we see a Midwestern woman in country clothes, wearing a cameo broach and an apron bordered with rick-rack stitching. In her hands she holds a plant pot containing a snake plant. She is the epitome of the pioneer woman, and this is a Renaissance-style work with its half-length figure in the foreground and a landscape backdrop and it is the inclusion of a windmill and sheaves of corn which marks it as an American Midwestern depiction. This was actually a portrait of his mother !

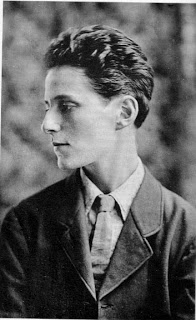

In August 1930 at the Iowa State Fair Grant Wood’s painting entitled Arnold comes of Age which was his portrait of twenty-one year old, Arnold Pyne, his assistant on the Memorial Window project.

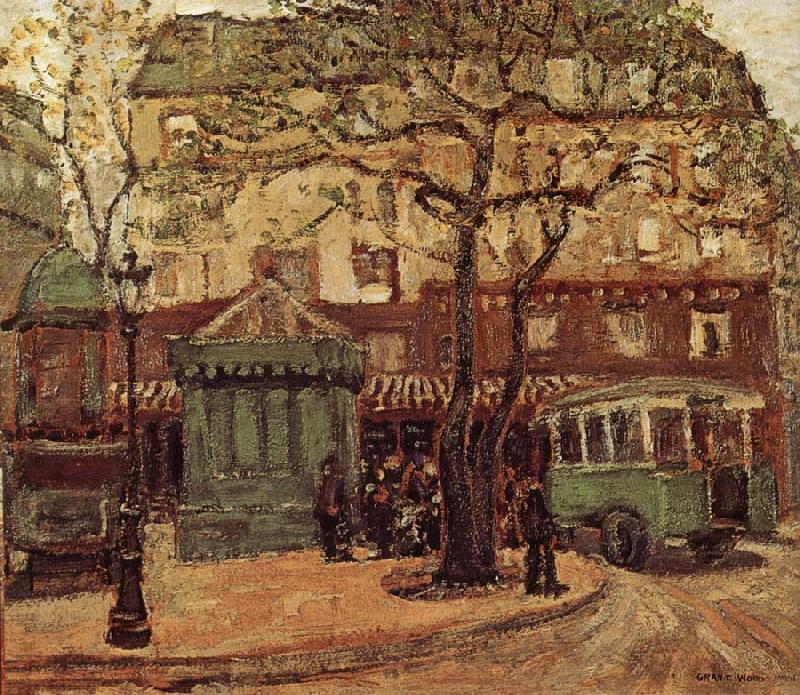

The renowned American journalist and correspondent for the Chicago Tribune from 1925 to 1932, covering Europe, William Shriver, once asked Grant Wood whilst in Paris, why, having witnessed the emerging art styles in Europe in the 1920’s, would his artistic style change. Wood answered by likening himself to the famous American novelist, short-story writer, and playwright, whose 1920 novel, Main Street, satirised the strict conservatism of small-town life. :

“…I am going home to paint those damn cows and barns and barnyards and cornfields and little red schoolhouses… and the women in their aprons and the men in their overalls and store suits… Isn’t that what Sinclair Lewis has done in his writing… Damn it, you can do it in painting too!…”

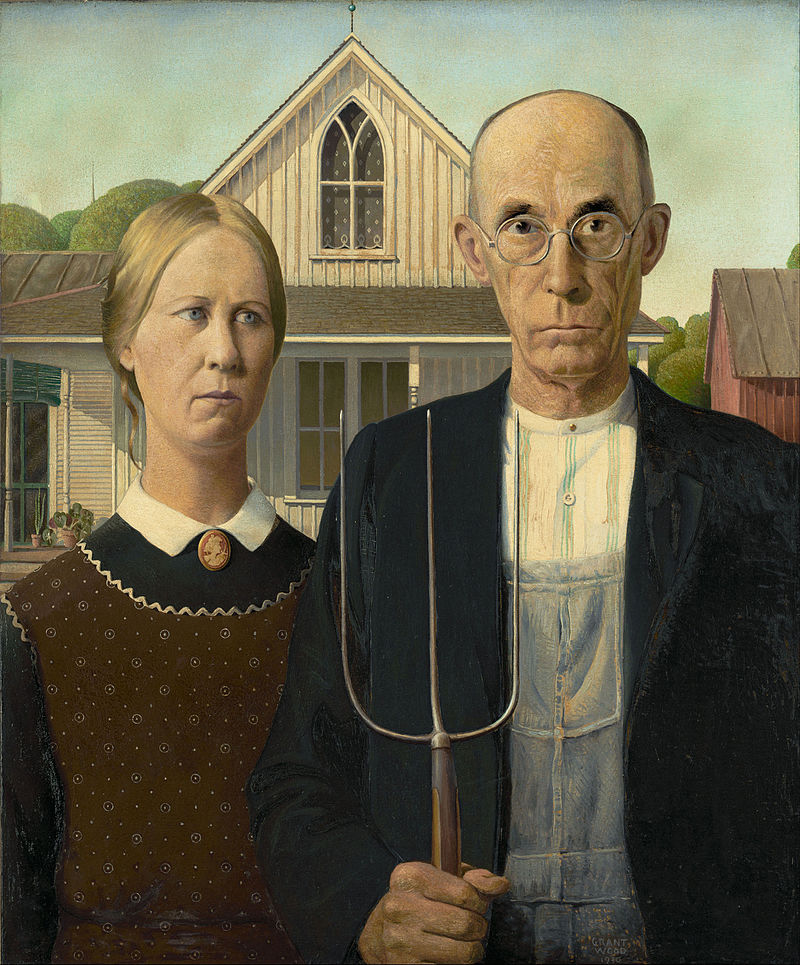

A year after the stained glass window was installed at the Veterans Memorial Building in Cedar Rapids, Grant Wood completed his iconic painting American Gothic, a painting which many consider to be the most famous painting in American art. So how did all come about?

In the spring of 1930, Grant Wood decided to take a weekend off from his painting and drove the 12o miles from his home in Cedar Rapids, to the home of one of his former student in Eldon, Iowa. The road trip passed through gently rolling patchwork of farmlands of central and south Iowa between the Cedar River to the Des Moines River. On a Sunday morning in early April, Wood came upon the now-famous house. It was known by the local residents as the Dibble House as it was built by Eldon resident, Charles Dibble, a Civil War veteran and livery stable owner in 1882 for his family, which included himself, his wife, and his eight children.

The house was built in a style known as Carpenter Gothic, or Rural Gothic, and is a North American architectural style-designation for an application of Gothic Revival architectural detailing and picturesque massing applied to wooden buildings erected by house-carpenters. This terminology is used when the design of lofty architecture of European cathedrals is applied to American frame houses. The Eldon house was a small, simple frame structure and was no different than many houses dotted around Wood’s home in Cedar Rapids. However, it had one unusual feature. On the second storey there was a single gable with an inset narrow Gothic window. The house mesmerised Wood and he began to wonder what type of people lived in such a house, so much so, after driving around the block he knocked on the door and introduced himself to the residents who showed him around the interior. After thanking the young couple he went back to his car, grabbed his paints and made a quick oil sketch of the house.

After he got back home he told his sister Nan about the house and how it had captivated him. The one aspect of the exceptional house which disappointed him was the fact that the residents were not whom he had envisioned for they were a young couple. He said to Nan:

“… I’ve decided to do a painting of the kind of people I think should live in that house. I thought about it last night. I have a woman in mind, Nan, but I’m afraid to ask her to pose, because, you know, like all the others, she’ll want me to make her look young and beautiful. And I’m not going to paint her beautiful in this picture. So she’ll be disappointed…”

Of course, we now know that the woman in the painting would be his thirty-one year old sister, Nan, but there lay the problem for Grant, for the woman he intended to paint was going to be an “old maid”. However, even knowing the problem he still asked his sister to pose and he showed her his preliminary oil sketch.

There was a long pause before Grant answered his sister’s question. Finally he addressed his sister asking her, if she was willing, to pose for the picture. He then had to sell the concept to her as he wanted the “daughter” to have a plain and old-fashioned appearance and her facial expression was to be one of sternness and sombreness. He asked Nan to imagine what it would be like to be under the control of her elderly and authoritarian father. Nan agreed and that afternoon went off to the store to buy some appropriate sombre brown and black clothes for the painting, as she later recalled:

“…. We were supposed to be small-town people. We were really not supposed to be farmers, but just small-town folk. We would own maybe a cow to milk, and we would have a little garden to tend for ourselves. But we’d keep all we grew and not sell anything in the market. Grant and I talked and talked about this. The man in the painting – who was supposed to be my father, would do some tinkering around the house, we decided. We tried to determine what the mother and wife would look like, but we just could not agree on anything. So we decided that the man was a widower. Now, when we talked about this, we tried to imagine what expression would be on the face of the man and his daughter. When we finished talking about this, I posed…”

Nan later remembered the posing for the painting:

“…It was really difficult because Grant was always joking. And both of us would break into laughter, and then we would have to start all over again. It was hard to go from being Grant Wood’s sister and joking with him in the studio to being a farmer’s daughter standing in front of a house. When I was posing and I lost my concentration, Grant would always draw me back to the work at hand by begging, ‘Come on, now, Nan. I’m trying to do your face and I really need you to look sour.’ So I looked sour, the best I could. And so he painted me…”

His depiction of a plain, stern-faced Iowa woman has an everlasting, inscrutable quality and some who saw the painting called her the “American Mona Lisa.”

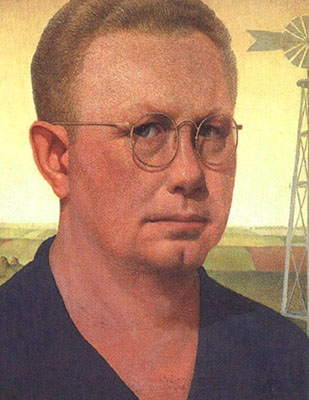

Grant explained to her that he would paint the house in the background and, standing side by side in front of it would be an elderly man and his daughter and that he intended to approach his sixty-three year old dentist, Byron McKeeby, to pose as the man. Grant had exchanged some of his paintings in lieu of payment for dental work with him and he knew McKeeby liked his work, so he was sure he would pose for the painting.

For Nan, Grant could do no wrong, and she was a constant source of encouragement to her brother. She had no misgivings about posing for the American Gothic painting even though she knew ahead of time it would probably be very unflattering. However, she harboured no resentment towards her brother, once saying:

“…Grant made a personality out of me. I would have had a very drab life without it…”

Some say the pair depicted were husband and wife but Grant’s sister Nan maintained it was father and daughter so that she was not to be classified as a woman who would marry a much older man. Grant, himself, never clarified the status of the pair !

The stern-looking man was posed by Wood’s Cedar Rapids’ dentist Byron McKeeby. We see McKeeby dressed in a black jacket and collarless shirt and clean denim overalls. In his right hand he holds a three-pronged pitch fork, the prongs of which are echoed in the stitching of his overalls and again in the Gothic window of the house. Although the depiction of the couple looks suitably posed Wood painted the two people separately and his sister and the dentist never stood together in front of the house.

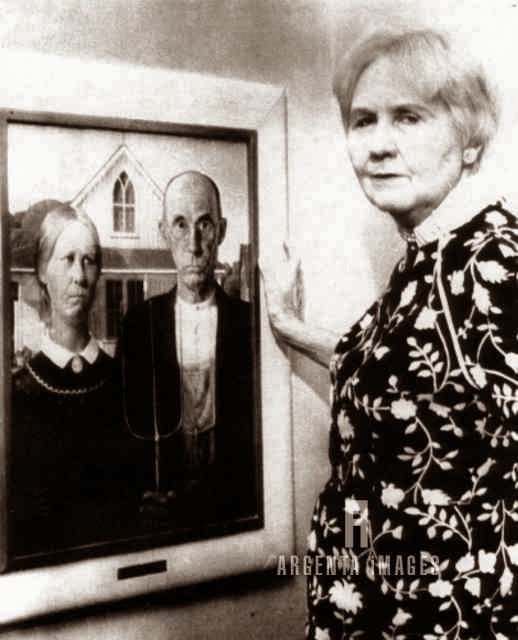

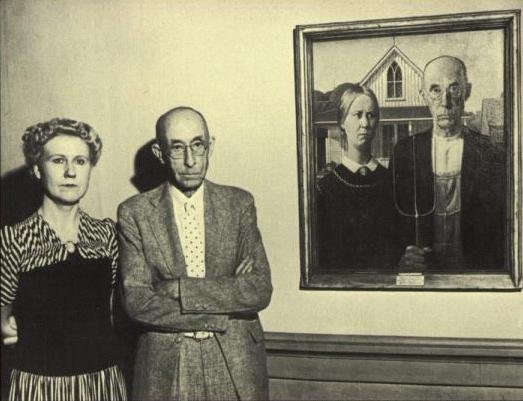

Comments about Nan as the model were often derogatory with one viewer writing that her face “would sour milk”. Other women protested that Nan was poking fun at them with her dour expression.

American Gothic was displayed in Cedar Rapids after Wood’s death in 1942. Nan, at that time, Mrs Wood Graham, and Dr. Byron McKeeby were united with each other and the painting for the first time, with their “stretched out long” faces as dour as ever !

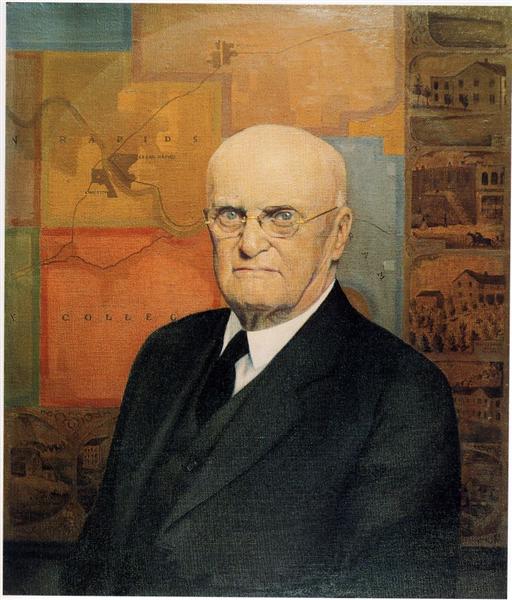

Grant submitted the painting to the jury for the forty-third annual exhibition of American paintings and sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1930. The judges dismissed it as a trifling “comic valentine,” but a powerful museum patron urged them to reconsider. The painting was awarded the Norman Wait Harris Bronze Medal, as well as a three-hundred-dollar prize. The painting was bought by the Friends of American Art at the Institute for another three hundred dollars. Newspapers throughout America soon carried articles and reproductions of the painting. Eventually, the picture appeared in the Cedar Rapids Gazette, which caused great consternation with the real Iowa farmers and their wives and they were not amused. To them, the painting looked like a nasty caricature, portraying Midwestern farmers as pinched, grim-faced, puritanical Bible-thumpers. However, the painting, which is now housed at the Art Institute of Chicago, is one of the most iconic and recognizable images in American art, and it helped propel Wood to fame and launch the Regionalist movement, of which Wood became the de facto spokesperson.

The highly detailed style of the work and the two unbending figures at the forefront of the depiction were inspired by the Flemish Renaissance art, that Wood would have seen during his European travels between 1920 and 1926. Despite the negative comments that Wood was belittling the Mid-Western folk he actually intended the painting to be an upbeat declaration about rural America and rural American principles. Remember, the year before American Gothic was shown at the Art Institute of Chicago, the country was hit by the great depression and America was facing a major crisis. In the Mid-West there was overproduction in agriculture, as farming techniques improved, and farmers started producing too much food. Coupled with the fact that there was less demand from Europe for food from America because they could grow their own crops. This abundance of crops led to falling prices and thousands of farmers became unemployed after having to sell their farms. Despite this Wood wanted his painting to be a positive statement about rural American values, and for it to become an image of comfort and encouragement at a time of great displacement and disenchantment. For Wood the man and his daughter were symbols of survivors who would battle on through the tough times.

Grant Woods, as a token of his gratitude, and maybe knowing of the hurtful remarks about his sister’s appearance in the painting, painted a formal portrait of her in 1931. Tripp Evans, a biographer of Grant Wood, wrote:

“…It’s really kind of a love letter from Grant to his sister. He adored Nan. And it’s a painting that he felt very close to as well, one of very few of his mature paintings that he kept for himself…”

In the painting, Portrait of Nan, he depicts her in fashionably marcelled hair style. The Marcelled hair style was a popular hairstyle of the 1920’s and 1930’s that featured unique waves and styling. Marcel Waves are a deep waved hairstyle reminiscent of American actress and bombshell Jean Harlow. Nan is shown wearing a patent-leather belt and a sleeveless polka-dot blouse. She is holding a plum in her left hand whilst the right-hand cups a small chicken. Nan is depicted as a chic-looking and chick-holding modern woman ! Grant Wood bought the little chick at a dime store but it proved to be an unwilling “sitter” for him. His sister Nan recalls the problems her brother had with the chick:

“…Grant kept long hours when he was on a painting spell and would work well into the night. The chick adjusted to his hours and made an awful fuss if it was sent to bed—actually, a crock Grant kept in the closet—before 2 or 3 a.m. It was also fussy about its victuals. It wouldn’t eat toast without butter or potatoes without gravy. One evening, the chick was acting up while company was over, so Grant deposited it in the crock, placed a book on top and forgot all about it. By morning, deprived of air, butter and gravy, the chick was in a dead faint. We threw water on the chick and fanned her for almost an hour before she came to. It was a close shave. She was pretty weak, and Grant didn’t have her do much posing that day…”

So why were the chicken and the plum featured in the portrait. Wanda Corn a leading Grant Wood scholar knew Nan well before she died, at age 91, and in 1990 wrote about the portrait:

“…He [Grant] undoubtedly liked the chicken because as it perched, young and vulnerable, in the cupped hand of his sister, it conveyed her tenderness. And the plum because, as an artistic convention, fruit has always symbolized femininity…”

So according to Wanda Corn, the two images represented, for Wood, all that was beneficial and wholesome about the Midwest. Many believed the chicken and the plum were symbolic but Grant’s sister Nan had a more down to earth reasoning for the inclusion of the chicken and the plum. In 1944 she wrote about the portrait:

“…Grant said the chicken would repeat the colour of my hair and the plum would repeat the background…”

Nan’s role as a model for Grant’s paintings ended with Portrait of Nan, Tripp Evans wrote in his 2010 book, Grant Wood: A Life:

“…After completing the painting, Wood reportedly told his sister, ‘It’s the last portrait I intend to paint, and it’s the last time you will ever pose for me.’”

She was surprised—she’d spent years posing for him—and asked for an explanation.

Wood said, “Your face is too well known…”

..……to be continued

In my final blog about Grant Wood I will look at his later years, showcase more of his paintings and talk about a rumour concerning the artist which would never go away.

Apart from Wikipedia much of the information about the artist and his paintings came from:

Cedar Rapids Museum of Art

http://www.crma.org/content/Collection/Grant_Wood.aspx

Sullivan Goss an American Gallery

http://www.sullivangoss.com/Grant_Wood/#Bibliography

Nan Wood’s scrapbook

http://digital.lib.uiowa.edu/cdm/ref/collection/grantwood/id/880

Eldon House

http://lde421.blogspot.com/2011/12/american-mona-lisa-profile-of-nan-wood.html

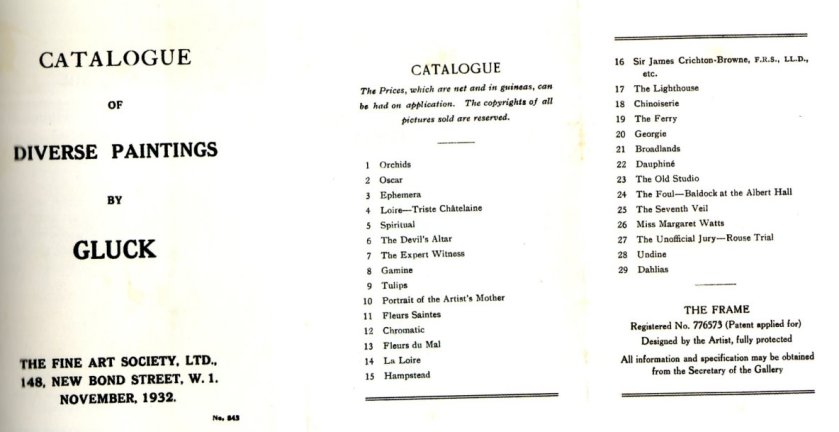

Most of the information for this blog came from two excellent books – Gluck: Her biography by Diana Souhami.

Most of the information for this blog came from two excellent books – Gluck: Her biography by Diana Souhami. Gluck Art and Identity by Amy De La Haye (Author), Martin Pel (Author), Gill Clarke (Author), Jeffrey Horsley (Author), Andrew Macintos Patrick (Author)

Gluck Art and Identity by Amy De La Haye (Author), Martin Pel (Author), Gill Clarke (Author), Jeffrey Horsley (Author), Andrew Macintos Patrick (Author)

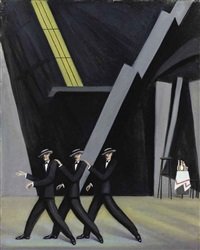

This close relationship with Nesta was to lead to Gluck’s most famous painting, completed in 1936, known as Medallion or the YouWe painting. The work is a portrait of Gluck and Nesta Obermer and according to Gluck it came about after the two women went to see the Mozart opera, Don Giovanni at Glynbourne on June 23rd 1936. Nesta and Gluck sat in the third row of the stalls and Gluck recalled how she felt the intensity of the music which fused them into one person and matched their love. In her biography of Gluck, Diana Souhami describes the painting:

This close relationship with Nesta was to lead to Gluck’s most famous painting, completed in 1936, known as Medallion or the YouWe painting. The work is a portrait of Gluck and Nesta Obermer and according to Gluck it came about after the two women went to see the Mozart opera, Don Giovanni at Glynbourne on June 23rd 1936. Nesta and Gluck sat in the third row of the stalls and Gluck recalled how she felt the intensity of the music which fused them into one person and matched their love. In her biography of Gluck, Diana Souhami describes the painting:

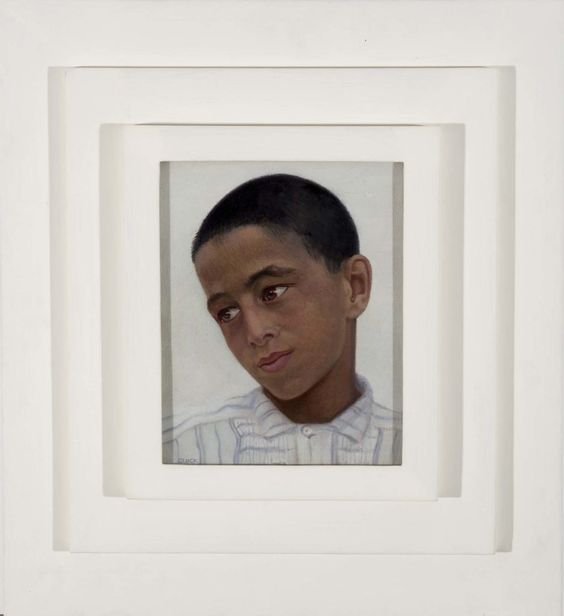

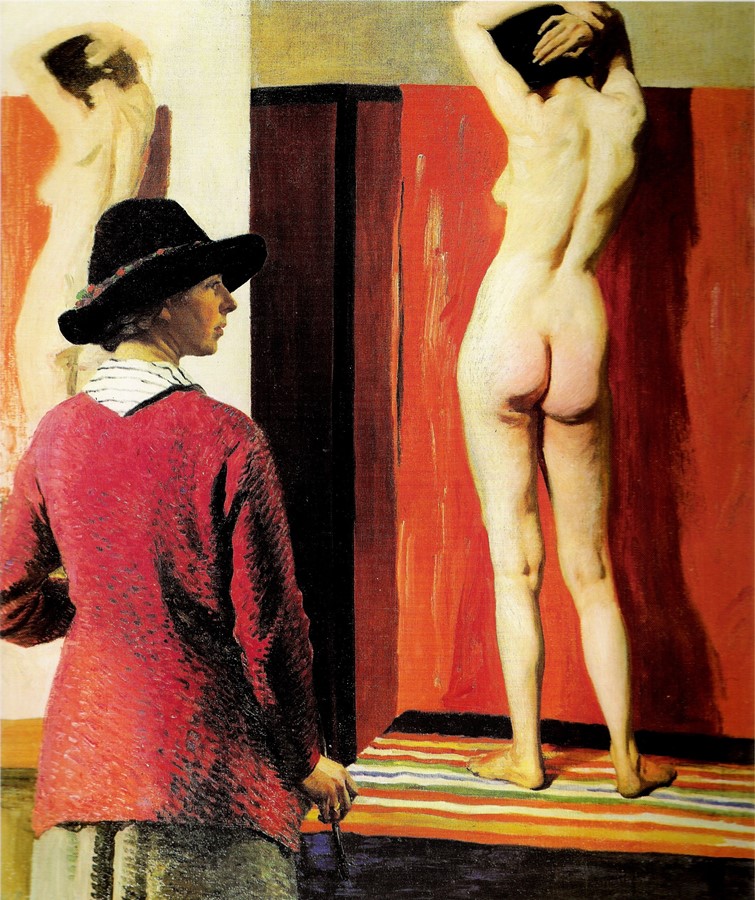

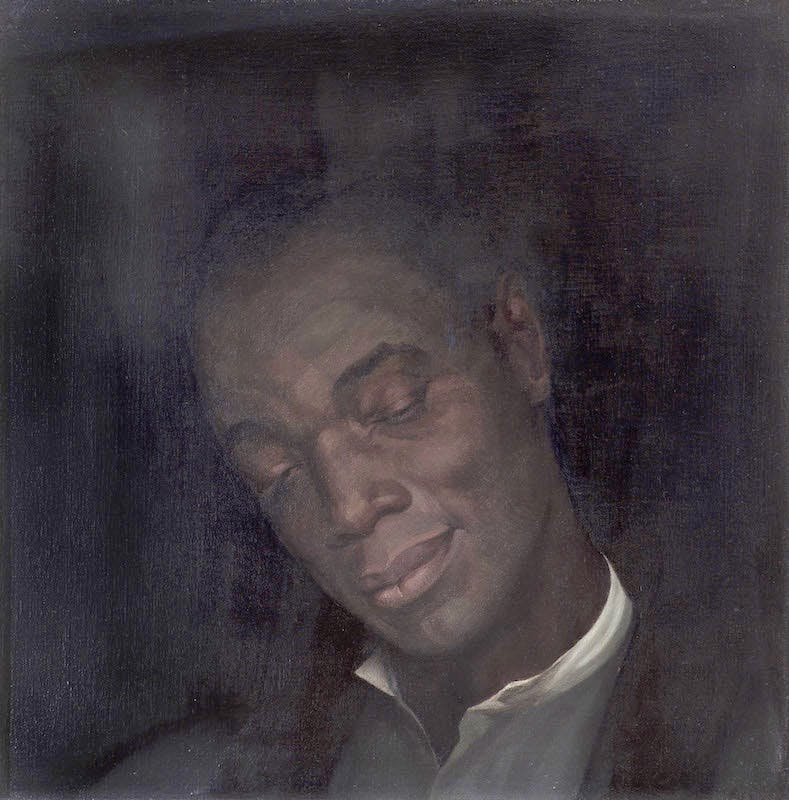

One of her pictures from those North African stays is a depiction of the head of a young Arab boy. She said that she was madly excited by the beauty and subtlety of the skin of the boy. She commented:

One of her pictures from those North African stays is a depiction of the head of a young Arab boy. She said that she was madly excited by the beauty and subtlety of the skin of the boy. She commented:

Most of the information for this blog came from the excellent book – Gluck: Her biography by Diana Souhami.

Most of the information for this blog came from the excellent book – Gluck: Her biography by Diana Souhami.

Most of the information for this blog came from the excellent book – Gluck: Her biography by Diana Souhami.

Most of the information for this blog came from the excellent book – Gluck: Her biography by Diana Souhami.

Most of the information for this blog came from the excellent book – Gluck: Her biography by Diana Souhami.

Most of the information for this blog came from the excellent book – Gluck: Her biography by Diana Souhami.